Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a major pathogen implicated in skin and soft tissue infections, abscess in deep organs, toxin mediated diseases, respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, post-surgical wound infections, meningitis and many other diseases. Irresponsible and over use of antibiotics has led to an increased presence of multidrug resistant organisms and especially methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as a major public health concern in Afghanistan. As a result, there are many infections with many of them undiagnosed or improperly diagnosed. We aimed to establish a baseline of knowledge regarding the prevalence of MRSA in Kabul, Afghanistan, as well as S. aureus antimicrobial susceptibility to current available antimicrobials, while also determining those most effective to treat S. aureus infections.

Methods

Samples were collected from patients at two main Health facilities in Kabul between September 2016 and February 2017. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles were determined by the disc diffusion method and studied using standard CLSI protocols.

Results

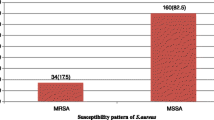

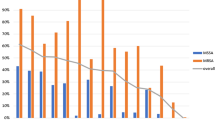

Out of 105 strains of S. aureus isolated from pus, urine, tracheal secretions, and blood, almost half (46; 43.8%) were methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) while 59 (56.2%) were Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). All strains were susceptible to vancomycin. In total, 100 (95.2%) strains were susceptible to rifampicin, 96 (91.4%) susceptible to clindamycin, 94 (89.5%) susceptible to imipenem, 83 (79.0%) susceptible to gentamicin, 81(77.1%) susceptible to doxycycline, 77 (77.1%) susceptible to amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, 78 (74.3%) susceptible to cefazolin, 71 (67.6%) susceptible to tobramycin, 68 (64.8%) susceptible to chloramphenicol, 60 (57.1%) were susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 47 (44.8%) susceptible to ciprofloxacin, 38 (36.2%) susceptible to azithromycin and erythromycin, 37 (35.2%) susceptible to ceftriaxone and 11 (10.5%) were susceptible to cefixim. Almost all (104; 99.05%) were resistant to penicillin G and only 1 (0.95%) was intermediate to penicillin G. Interestingly, 74.6% of MRSA strains were azithromycin resistant with 8.5% of them clindamycin resistant. Ninety-six (91.4%) of the isolates were multi-drug resistant.

Conclusions

There was a high rate of Methicillin resistance (56.2%) among S. aureus strains in the samples collected and most (91.4%) were multidrug resistant. The most effective antibiotics to treat Staph infections were vancomycin, rifampicin, imipenem, clindamycin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefazolin, gentamicin and doxycycline. The least effective were azithromycin, ceftriaxone, cefixim and penicillin. We recommend that, where possible, in every case of S. aureus infection in Kabul, Afghanistan, Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) should be performed and responsible use of antibiotics should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is a major pathogen implicated in skin and soft tissue infections [1]. Multidrug resistance in Staphylococci is an increasing problem in clinical practice especially methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains. These strains are resistant to most of the antimicrobial agents, and isolates with reduced susceptibility and resistance to vancomycin, which is the last drug for the treatment of MRSA infections [2]. These multidrug resistant strains may cause severe infections with a high rate of mortality. In vitro susceptibilities of MRSA strains, especially those from community-acquired infections, to clindamycin, macrolides, quinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole have frequently been reported [3, 4]. Strains of MRSA, which had been largely confined to hospitals and long-term care facilities, are emerging elsewhere in the community. The changing epidemiology of MRSA bears striking similarity to the emergence of penicillinase-mediated resistance in S. aureus decades ago [5]. One of the best choices of treatment of MRSA is to treat with clindamycin and fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin, but recent studies showed that susceptibility of this microorganism is also decreasing to clindamycin and fluoroquinolones [6, 7].

In a study in southern districts of Tamilnadu, India [8], the prevalence of MRSA strains isolated from clinical and carrier samples were 37.9%. Almost all clinical MRSA strains (99.6%) were resistant to penicillin, 93.6% to ampicillin, and 63.2% towards gentamicin, co-trimoxazole, cephalexin, erythromycin, and cefotaxime. All MRSA strains (100%) of carrier screening samples had resistance to penicillin and 71.8% and 35.9% respectively were resistant to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole. However, all strains of clinical and carrier subjects were sensitive to vancomycin. In this study, it was concluded that the determination of prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of MRSA would help the treating clinicians for first line treatment in referral hospitals.

A study in a hospital in Turkey aimed to determine the susceptibility patterns of Staphylococcus aureus strains to various antimicrobials, 50.2% were resistant to methicillin. All strains were susceptible to vancomycin, teicoplanin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and linezolid. It was found that 53.4% MRSA strains were erythromycin resistant, and 39.6% showed constitutive clindamycin resistance. In this study they identified the high rate of methicillin resistance among S. aureus strains in their hospital [9].

In Afghanistan the widespread use of antibiotics has led to increase in the number of multidrug resistant organisms including MRSA [10, 11]. A study in Afghanistan, showed that there is a significant amount of overuse and abuse of antimicrobials in primary health care clinics that may lead to problem of antimicrobial resistance [12]. Another study at a US military hospital in Bagram Airbase in Afghanistan, found that Afghan patients often carry multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria compared to US citizens treated in this hospital. Their findings suggested the need for effective infection control measures at deployed hospitals where both soldiers and local patients are treated [13].

Indeed, some strains have become resistant to practically all of the commonly available antibiotics in Afghanistan. That is why the physicians mostly prescribe new antibiotics in order to get positive results without knowing the susceptibility patterns of causative bacterial agents [11]. There is no study regarding the prevalence of MRSA which is a multidrug resistant bacteria and its susceptibility patterns to most common antibiotics in Afghanistan, which causes severe infections with a higher mortality rate both community and hospital acquired infections. The aim of this study is to assess the prevalence of MRSA, as well as determining antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of S. aureus strains to common antibiotics available in Kabul, Afghanistan. The results of this study would help physicians in Kabul to know the prevalence of MRSA and to help them change their treatment protocols, and to know the importance of bacteriological culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST). It would also be helpful for the Ministry of Health of Afghanistan to pay more attention to diagnostic labs and the role of bacteriological culture and AST to provide better treatment outcomes and responsible use of antibiotics. The findings would also emphasize the importance of local surveillance in generating relevant local resistance data that can guide empiric therapy.

Methods

This longitudinal study was conducted in the Microbiology Laboratory of the Faculty of Pharmacy of Kabul University between September 2106 and February 2017. Presumptive isolates from various clinical samples were brought from two main health facilities of Kabul, to the microbiology lab of the Faculty of Pharmacy. All of the isolates were collected from clinical specimens obtained from hospitalized patients. The standard microbiological procedures were conducted with minimum delay for culture, confirmatory tests and AST. We selected two main health facilities in Kabul, because they have standard microbiology labs and perform most of the bacteriological cultures and identification in Kabul. Confirmatory tests were carried out for diagnosis of S. aureus strains, by inoculating presumptive isolates onto Blood agar base medium (Oxoid, England) to which 5% sheep blood was added. All cultured media were incubated at 37 °C for 18–24 h under aerobic condition. The suspected isolated colonies were subjected to Gram’s staining, Catalase test, Coagulase test, and Mannitol fermentation on Mannitol Salt agar (Oxoid, England) [14]. Confirmed S. aureus isolates were subjected to AST by Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method as per Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [15] on Muller Hinton agar (Oxoid, England) for 20 antimicrobials such as: penicillin G (P,1unit), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (AMC, 30μg), oxacillin (OX, 1μg), azithromycin (ATH, 15μg), erythromycin (E, 15μg), cefazolin (CZ, 30μg), ceftazidime (CAZ, 30μg), cefoxitin (FOX, 30μg), cefixim (CFM, 5μg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30μg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT, 1,25/23,75μg), gentamicin (CN, 10μg), tobramycin (TOB, 10μg), doxycycline (DO, 30μg), imipenem (IMI, 10μg), clindamycin (CD, 2μg), vancomycin (VA, 30μg), chloramphenicol (C, 10μg) and rifampicin (RP, 5μg).

The growth suspension for AST was prepared in 5 ml Normal saline solution and the turbidity was adjusted to match that of 0.5 McFarland standards to obtain approximately the organism number of 1 × 106 colony forming units (CFU) per ml. Antibiotic discs were placed after 15 min of inoculation to Muller Hinton agar seeded with each isolate and were incubated for 18–24 h at 35–37 °C. The diameter of the zone of inhibition around the disc was measured using sliding metal caliper. For accuracy, during the antibiotic screens, three independent replicates were performed. The susceptibility of all isolates were determined against different classes of antibiotics as follows:

For detection of MRSA we applied two definitions: [1] inhibition zone less than or equal to 23 mm on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) with 30 μg cefoxitin disc seeded with growth suspension of S. aureus isolates adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards at 37 °C for 18-24 h [16]; [2] inhibition zone on MHA containing 2% NaCl with 1μg oxacillin disc less than or equal to 10 mm seeded with growth suspension of S. aureus isolates adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards at 30 °C for 18-24 h [17].

For detection of Multi Drug Resistance, we used the definition of Magiorakos et al. [18] as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories.

Statistical analysis and quality assurance

The reliability of the study findings was guaranteed by implementing quality control measures throughout the whole processes of laboratory work. We used two strains of S. aureus as control. S. aureus ATCC 29213 a mecA negative strain, and S. aureus ATCC 43300 a mecA positive strain; both confirmed with standard PCR as reference methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA strains respectively using the DNA amplification instrument Mastercycler gradient (Eppendorf, Germany).

The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 19. Binary logistic regression was used to determine the association between S. aureus infection, gender and age. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to control confounding factors. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Of 105 strains of S. aureus isolated from various types of pus, urine, tracheal secretions and blood, 46 (43.8%) were MSSA while 59 (56.2%) were MRSA. All strains (105; 100%) were susceptible to vancomycin. Almost all (104; 99.05%) were resistant to penicillin G and only 1 (0.95%) was intermediate to penicillin, for further information please refer to Table 1.

We did not find any strain of MSSA to be resistant to clindamycin and only 6.5% were intermediate to clindamycin, while 8.5% of MRSA strains were resistant to clindamycin. Susceptibility to azithromycin was low in both MSSA (52.2%) and MRSA (23.7%). MSSA vs MRSA isolates showed a higher susceptibility to amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, 2nd and 3rd generation of cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, rifampicin, and co-trimoxazole, for further information please refer to Table 2.

The difference of MRSA infection was not statistically significant according to gender (p = 0.42). Of 59 MRSA strains isolated, 44 (74.6%) were from males while 15 (25.4%) from females. According to category of age, the prevalence of MRSA was 39.0% in ages between 1 and 17 years, 39.3% in ages between 18 and 40 years and 66.7% in ages between 41 and 75 years old. The difference of MRSA distribution was not statistically significant according to age (p = 0.50), and health facility (p = 0.95).

Specimen-wise distribution showed that MSSA vs MRSA in blood was (44% vs 56%), in ear pus (50% vs 50%), in pus from other sites of the body (44% vs 56%), in urine (33% vs 67%), and in tracheal secretions (50% vs 50%). The specimen wise distribution of MSSA and MRSA was not significantly different (p = 0.96).

In males the percentage of MSSA was 31 (41.3%) versus MRSA 44 (58.7%), and in females, MSSA 15 (50%) versus MRSA 15 (50%). The difference of MRSA distribution was not significant according to gender (p = 0.52).

Multi-drug resistance (MDR) pattern of S. aureus

Eighty-eight (83.8%) of the isolates were multi-drug resistant. Multi-drug resistant strains ranged from resistance to three classes of antibiotics (11, 10.48%) to 9 classes of antibiotics (1, 0.95%). The highest rate of MDR were observed for 4–5 classes of antibiotics (28, 26.67%). Details of resistance to different antibiotics are described in Table 3.

Discussion

In our study, methicillin resistant S. aureus was found to be 56.2%. There is no previous information regarding prevalence of MRSA in Afghanistan. In West Asia, MRSA prevalence ranges from 12% to 49.4% in six different hospitals of Saudi Arabia [19]. In European countries, MRSA rates varied from 0.6% in Sweden to 40.2–45% in Belgium, Greece, Ireland, Italy, and the United Kingdom [20, 21], because the use of antibiotics are much more controlled in these countries. In Turkey, the proportion of MRSA were reported to be 50.2% [9] which is similar to European countries. In a study performed in 17 different regions of Russia, methicillin resistance among S. aureus strains was between 0% and 89.5% [22] which is very diverse. In a systemic review in Iran, the prevalence of MRSA was determined to be approximately 56.5% (ranged between 50 and 60%) [23], which is similar to our findings and the similarity would be due to irresponsible use of antibiotics in both countries.

We found that the prevalence of MRSA among patients in our study to be 56.2% which is higher compared to findings of a similar study conducted in Peshawar Pakistan, which is very close to Afghanistan. In that, study the researchers examined 280 isolates of S. aureus recovered from hospitalized patients, and indicated that 36.1% of Staphylococci were detected as MRSA [24]. There was also a significant difference between gender and MRSA infections. In our study, 74% of MRSA isolates were from males. As compared to the study from Pakistan, 34% of MRSA infections were from males. According to age in both studies the prevalence of MRSA infections were higher among elderly in Pakistan and Afghanistan 60.71% and 66.7% respectively, which is a known risk factor for MRSA infections, however in both studies it was not statistically significant. The prevalence of MRSA infection in the present study did not vary significantly by gender (p = 0.42), age group (p = 0.50), specimen (p = 0.96) and health facility (p = 0.95). This is in agreement with earlier reports by Geyid et al. [25] indicating that gender and age are not risk factors for the acquisition or colonization of MRSA.

In our study, despite the high prevalence of MRSA, there was no isolate with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin, however we could not include other new antibiotics like teicoplanin, linezolid and quinupristin/dalfopristin in our study to assess their efficacy as well, because these antibiotics are not included in the licensed and official medicine list of Afghanistan and therefore are not available in Afghanistan [26].

In this study, it was observed that 8.5% of the MRSA strains were resistant to rifampicin and clindamycin and 16.9% were resistant to imipenem; this is probably because these antibiotics are not widely used in the treatment of Staph and other bacterial infections in clinics in Afghanistan and are mostly effective in the treatment of sensitive G+ and G- bacteria. Most of the MRSA isolates were resistant to multiple other antimicrobial agents like cefixim (96.6%), ceftazidime (93.2%).

Interestingly, ceftriaxone, which is widely used in Kabul and other provinces of Afghanistan, we found that 44.1% of MRSA strains were resistant to this antibiotic and 49.2% intermediate and only 6.8% were susceptible. This is an alarming sign, which highlights widespread use of this antibiotic and other similar broad spectrum antibiotics in clinical settings and increased resistance toward third generation cephalosporins. In general, elevated rates of multidrug resistance may emerge from diverse isolates of S. aureus under antimicrobial pressure or as a result of widespread person to person transmission of multidrug resistant isolates [27]. In our study, although imipenem resistance was detected in 81.4% MRSA strains, no resistance was detected in MSSA strains. In this study, cefazolin, gentamicin and ciprofloxacin were found to be more effective on MSSA than MRSA strains.

Interestingly 8.5% of MRSA strains were resistant to clindamycin, while there was no resistant strain of MSSA to clindamycin. We found that 6.5% of MSSA strains to be intermediate to clindamycin. Our findings support the previous study conducted by Frank, et al. [28] that clindamycin is effective for the treatment of infections caused by Staphylococci, or for patients allergic to beta-lactam agents [18, 29]. It is a good alternative to the treatment of both MSSA and MRSA infections.

Conclusions

The prevalence of MRSA strains obtained in this study was high (56.2%) when compared with the prevalence rates obtained from other similar studies conducted elsewhere. Most of S. aureus strains especially MRSA strains were multidrug-resistant and fortunately no isolate was resistant to vancomycin, the drug of choice for treating multidrug resistant MRSA infections. Isolates showed a higher susceptibility to vancomycin, clindamycin, rifampicin, imipenem, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, cefazolin, gentamicin, and doxycycline. The least effective were azithromycin, ceftriaxone, cefixim and penicillin.

Good infection control practices such as strict hand washing, identifying and treating MRSA carriers, as well as prudent use of antimicrobial agents is recommended. Further, genotypic studies are needed to characterize resistant strains of S. aureus.

Abbreviations

- AST:

-

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

- ATCC:

-

American Type Culture Collection

- CFU:

-

Colony Forming Unit

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- FMIC:

-

French Medical Institute for Children

- MDR:

-

Multi drug resistant

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

References

Franklin D, Lowy MD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–2.

Kim HB, et al. Vitro activities of 28 antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus isolates from tertiary-care hospitals in Korea: a nationwide survey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1124–7.

Hussain FM, Boyle-Vavra S, Bethel CD, Daum RS. Current trends in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a tertiary care pediatric facility. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1163–6.

Groom AV, et al. Et al. community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rural American Indian community. JAMA. 2001;286:1201–5.

Chambers HF. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis. 2001 Mar-Apr;7(2):178–82.

Siberry GK, et al. Failure of clindamycin treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expressing inducible clindamycin resistance in vitro. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(9):1257–60.

Blumberg HM. Rapid Development of Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Methicillin-Susceptible and -Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163(16):1279–85.

Rajaduraipandi K, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a multicentre study. J IAM. 2006;24:34–8.

Eksi F, et al. Determination of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from southeastern Turkey. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:57–62.

Calhoun JH, et al. Multidrug-resistant organisms in military wounds from Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(6):1356–62.

Bajis S, et al. Antibiotic use in a district hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan: are we overprescribing. Public Health Action. 2014;21(4):259–64.

Green T, et al. Afghanistan medicine use study: a survey of 28 health facilities in 5 provinces, 2010. MoPH.

Sutter DE, et al. High Incidence of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Recovered from Afghan Patients at a Deployed US Military Hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(9):854.

Delost MD. Introduction to diagnostic microbiology for the sciences. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning Company; 2015.

Barry AL, et al. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents; approved guideline. CLSI. 1999;

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Third Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S23. Wayne: S 2013.

Skov R, Smyth R, Larsen AR, et al. Phenotypic Detection of Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus by Disk Diffusion Testing and Etest on Mueller-Hinton Agar. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(12):4395–9.

Magiorakos PA, Srinivasan A, Carey BR, Carmeli Y, Falagas EM, Giske GC, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Baddour MM, Abuelkheir MM, Fatani AJ. Trends in antibiotic susceptibility patterns and epidemiology of MRSA isolates from several hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2006;5:30.

Blandino G, Marchese A, Ardito F, Fadda G, Fontana R, Lo Cascio G, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Italy from patients with hospital-acquired infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:515–8.

Sader HS, Streit JM, Fritsche TR, Jones RN. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-positive bacteria isolated from European medical centers: results of the Daptomycin surveillance Programme (2002-2004). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:844–52.

Stratchounski LS, Dekhnich AV, Kretchikov VA, Edelstain IA, Arezkina AD, Afinogenov GE, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of nosocomial strains of Staphylococcus aureus in Russia: results of a prospective study. J Chemother. 2005;17:54–60.

Ghasemian A, Mirzaee M. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) strains and the Staphy-lococcal cassette chromosome mec types in Iran. Infect Epidemiol Med. 2016;3:31–4.

Ullah A, Qasim M, Rahman H, Khan J, et al. High frequency of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Peshawar Region of Pakistan. Springerplus. 2016;5:1–6.

Geyid A, Lemeneh Y. The incidence of methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus strains in clinical specimens in relation to their beta-lactamase producing and multiple-drug resistance properties in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J. 1991;29:149–61.

Ministry of public health of Afghanistan. National licensed medicine list of. Afghanistan. 2014; Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js21738en/

Ayliffe GAJ. The progressive intercontinental spread of methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:74–9.

Frank AL, Marcinak JF, Mangat PD, Tjhio JT, Kelkar S, Screckenberger PC, et al. Clindamycin treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:530–4.

Ladhani S, Garbash M. Staphylococcal skin infections in children: rational drug therapy recommendations. Pediatr Drugs. 2005;7:77–102.

Acknowledgments

We thank the World Bank’s Higher education development program (HEDP) for financial support. In addition, we thank Dr. Tariq Mahmood and Dr. Esmat from French Medical Institute and Dr. Jawed Rahmani from Kabul Central Laboratory in Kabul and our Lab technician Homayoun Hashimi, for providing us the standard strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Many thanks as well to Dr. Jeff Armstrong from USWDP for assisting us in editing the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by World Bank’s Higher education development program (HEDP).

Availability of data and materials

All relevant materials and data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HMN has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and has given final approval to submit the manuscript to be published. HR was involved in conducting the study; drafting the manuscript; and statistically analyzing the data. AZN was involved in culture of strains and antibiotic susceptibility testing. MAB brought samples from health facilities to Microbiology Lab of faculty of Pharmacy and conducted preliminary identifications of strains. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Academic Council of the Faculty of Pharmacy and Research Committee of Kabul University with approval numbers: FoP.124, 12/7/2016 and KURC.115, 03/08/2016. The research committee of KU is considered the local research review board. According to the decision of local research review board, verbal consent from all participants was also obtained for specimens to be used in this study due to the illiteracy of some participants. However, this study was conducted on specimens from patients and not directly on patients. The specimens for this study were collected from French Medical Institute for Children (FMIC) and Kabul Central Laboratory (KCL), which are two main health facilities in Kabul.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Naimi, H.M., Rasekh, H., Noori, A.Z. et al. Determination of antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in Staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from patients at two main health facilities in Kabul, Afghanistan. BMC Infect Dis 17, 737 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2844-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2844-4