Abstract

Background

Scaling up HIV testing is the first step in the HIV treatment continuum which is important for controlling the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM). Following an online HIV testing intervention among MSM, we aim to examine sociodemographic and spatial factors associated with HIV testing.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis on data from an online HIV testing intervention among MSM who had never-tested for HIV. The survey was distributed through online networks connected to all provinces and regions of China. Univariate and multivariable analyses were performed to examine factors associated with testing three weeks post-intervention.

Results

At three weeks after the intervention, 36% of 624 followed-up MSM underwent HIV testing, 69 men reported positive HIV test results. Having money for sex, ever tested for sexually transmitted infections and intimate partner violence experience were significant factors of post-intervention HIV testing. Students were less likely to undergo HIV testing at follow-up compared to others (adjusted odds ratio=0.69, 95% C.I.=0.47–0.99), adjusted by age and type of intervention. Moderate provincial spatial variation of testing was observed.

Conclusions

While high risk men generally had higher HIV testing rates, some MSM like students had lower testing rates, suggesting the need for further ways to enhance HIV testing in specific MSM communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV testing is the first step in the HIV care continuum [1]. Expanding HIV testing results in larger number of individuals diagnosed with HIV, thereby introducing more opportunities to avert HIV transmission. In China, HIV testing coverage among men who have sex with men (MSM) has been low, with only 24% ever tested in the years 2000–2007 [2]. HIV prevalence among MSM in China increased from 1% in 2003 to 7.7% in 2014 [3]. Due partly to the Chinese National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program which began in 2003 (free testing, care and treatment) [4] and adoption of strategic plan targeting at MSM in 2007–2010, [5] the proportion of MSM who had ever undergone HIV testing increased to 47% by 2011 [2]. This is still far behind the UNAIDS target for 90% testing among infected individuals [6].

In the digital era, one way to enhance HIV testing is by disseminating HIV testing promotion messages through the internet. The internet provides an opportunity to deliver messages efficiently with fewer geographic constraints. MSM in China have high rates of internet and smart phone use, providing a foundation for online interventions [7]. HIV testing promotion using mass media such as short videos are commonly used to enhance HIV testing [8, 9]. The World Health Organization also advocated the use of media interventions to tailor HIV testing promotion among subgroups, especially key populations [10]. Most studies of mass media HIV testing interventions for MSM have been limited to high-income countries such as Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom [8, 11,12,13]. In view of high transmission risk of HIV among MSM in China, we examined sociodemographic and spatial factors associated with HIV testing following an online HIV testing intervention among never-tested MSM.

Methods

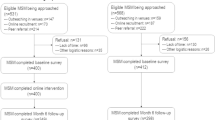

This is a secondary analysis of data from an online intervention that focused on promoting HIV testing in China in 2014 (study details elsewhere [14, 15]) In brief, 1424 MSM had been recruited online through community-based organizations with web portals based throughout China. Men who had anal sex with men at least once during their lifetime, were ≥16 year-old, and had never-tested for HIV were included. After completing an online survey, 721 never-tested participants (after excluding 703 (49.4%) ever tested participants) were randomly assigned to view either a crowdsourced video or health marketing video (one minute) that promoted HIV testing. Crowdsourcing is a bottom-up approach that uses crowd (non-professionals) wisdom to create a product or complete a task, while health marketing is a top-down approach based on professionals’ idea [16]. Three weeks following the intervention, 624 participants reported HIV test uptake and test results through text messaging, while 97 were lost to follow-up (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Honorariums (~8 USD phone card) were given to those who responded to the messaging.

Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression were used to identify factors associated with reported HIV testing at follow-up, which took place three-week after intervention. The factors examined were: socio-demographics (age, ethnicity, marital status, high education level attained, being student, annual income level and residing in city or countryside), sexual behavior (group sex defined as >2 persons engaged in sexual activity, and sex for money) in the past 12 months, history of suffering intimate partner violence (IPV) by their current male sexual partner and type of IPV experienced (details of IPV published elsewhere [17]), history of sexually transmitted infections (STI) testing, pre- and post-intervention intention of HIV testing in the next year and type of intervention received (health marketing or crowdsourced video). In multivariable logistic regression, besides the type of intervention video received, the following variables were explored as potential confounders: student status, being adolescent (≤19 year-old [18]), married and annual income >9677USD. If there was >10% change between crude odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) in the multivariable model with a confounder, we kept the confounder in the model. We have also examined the factors associated with reported HIV testing results (positive vs negative) in bivariate analyses.

To account for the clustering of HIV testing which might exist in 32 provincial-level administrative divisions (named as provinces hereafter), we performed binomial multilevel models using R 3.2.1 lme4 package. In the model, MSM (level 1) were nested by provinces (level 2). Empty multilevel models were developed to examine the homogeneity of outcomes across provinces. If heterogeneity existed, explanatory multilevel models were performed separately to include variables at individual level (same as those factors listed in logistic regression models) and province level (retrieved from China Statistical Yearbook 2014 http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2014/indexch.htm). Provincial level factors included population size, number of males aged 15 or above, size and proportion of urban population, total and per capita gross regional product of the province. Provincial heterogeneity was tested by median odds ratio (MOR), with 1 denoting the absence of heterogeneity and >1 for higher heterogeneity [19].

Results

Baseline characteristics

All never-tested MSM responding to follow-up message (n = 624) were included in this study. At baseline, the median age was 22 years old (interquartile range (IQR) = 20–26) and half of the men were students (Table 1). A majority were not married (90%), had received at least high school education (72% diploma or above), earned below 9677 USD in a year (86%) and were living in a city instead of rural area (87%). In the past 12 months, 7% of men had group sex and 5% had sex for money. A total of 286 (46%) intended to test for HIV in the following year before intervention, and the figure increased to 388 (62%) after intervention.

Factors associated with HIV testing at follow-up

Among 624 MSM, 225 (36%) self-reported HIV testing, of which 69 claimed to have been tested HIV positive. The HIV prevalence ranged between 11% (69/624, assuming those non-tested were HIV negative) and 31% (69/225). Comparing with HIV negative respondents, reported HIV positive respondents were more likely to be adolescent (HIV negative: 17% vs HIV positive: 29%; OR = 1.95, 95% C.I. = 1.003–3.79) and with lower education level (HIV negative: 23% vs HIV positive: 48%, OR = 3.06, 95% C.I. = 1.67–5.58). Other characteristics, including other socio-demographics, sexual behavior, experience of IPV and history of STI testing, were not significantly different between reported HIV positive and negative respondents (results not shown).

In multivariable logistic regression with confounders of intervention type and age (continuous variable), students were less likely to have undergone HIV testing than non-students (aOR = 0.69, 95% C.I. = 0.47–0.99) (Table 2). Adjusted by intervention type, men ever tested for STIs (aOR = 2.17, 95% C.I. = 1.31–3.61) were more likely to test for HIV. In addition, HIV testing intention before intervention (aOR = 2.39, 95% C.I. = 1.71–3.34) and after intervention (aOR = 2.94, 95% C.I. = 2.03–4.26) were positively associated with HIV testing at follow-up, and with higher odds for post-intervention testing intention.

Risky sexual behaviors of sex for money (aOR = 2.97, 95% C.I. = 1.44–6.10) were more likely to be associated with HIV testing. Among 257 men responding to questions related to IPV (the rest not responded to the question), 29% self-reported any type of IPV experience, and the latter were also more likely to test for HIV (aOR = 2.44, 95% C.I. = 1.40–4.23). Specific types of IPV, including being hit or thrown objects, threatened to stop financial help, threatened to harm the person or persons they care for, and threatened to reveal their sexuality were positively associated with HIV testing at follow-up.

Geographically, the median proportion of testing across provinces was 35% (IQR = 25%–46%, n = 26), excluding 6 provinces with ≤5 men in this study. (see Fig. 1 for geographic distribution) Moderate heterogeneity of HIV testing rate at follow-up in 32 provinces was observed with MOR = 1.34. In explanatory multilevel models, having sex for money (aOR = 2.88, 95% C.I. = 1.38–6.01), history of STI testing (aOR = 2.11, 95% C.I. = 1.26–3.55) and intention of HIV testing at baseline (aOR = 2.38, 95% C.I. = 1.69–3.33) and after intervention (aOR = 2.90, 95% C.I. = 2.00–4.22) remained significant positive predictors of HIV testing. However, association of neighborhood effect of province-level factors such as population size or gross regional product with HIV testing was not observed.

Discussion

In this study, we found that 36% of MSM without previous HIV testing underwent HIV testing after an online intervention. The prevalence of self-reported HIV infection ranged from 11% to 31%. The lower bound estimation was higher than the national HIV prevalence study among MSM [3]. The lower estimated prevalence in the previous study might be contributed by lower risk between HIV tests among MSM with regular testing behavior. This study focused on the factors significantly associated with first-time HIV testing following an online intervention. Demographically, students had a lower HIV testing rate while men with more risky behaviors had a higher HIV testing rate. Previous studies have examined HIV testing mass media interventions [20]. Several studies identified subgroups not effectively reached by such interventions [8, 20]. Our study expands the literature by identifying the characteristics of MSM who were more likely to undergo HIV testing following online intervention in a middle-income country, and examining spatial variation in effects.

Geographically, moderate provincial variation of testing rate at follow-up was found. Moderate provincial variation towards HIV testing action was probably due to the variation of local HIV testing facilities, which we however do not have the data to fit in the model here. Spatial barriers of service utilization and spatial variation in HIV testing rate can be reduced by decentralization of testing sites, as observed in Mozambique [21]. With the expansion of HIV testing services in China in recent years, [2] smaller variation of provincial HIV testing rate is expected.

Though the proportion of men with risky sexual behaviors (having sex for money) was small (7% of never-tested men), they were more likely to have HIV testing at follow-up. A high proportion of high risk MSM (38% of those having group sex and 45% of those having sex for money) claimed to be HIV positive, though these risk behaviors were not significantly associated with HIV positive status. Conversely, men without high risk sexual behaviors were less likely to go for HIV testing, probably because of their low perceived risk of infection, which is consistent with other studies for never-tested MSM [22, 23]. On the other hand, IPV experience was found to be significantly associated with high risk behaviors of group sex [17] and having sex for money [17, 24]. In our study, 29% (74 out of 257) of never-tested men at follow-up had experienced IPV. We found that several types of IPV were positively associated with post-intervention testing, which was consistent with a previous study in the U.S. showing similar associations [25]. They were also positively associated with HIV diagnosis [17].

Half of the study population was students. They were less likely to have HIV testing. Even though no significant difference of testing rate was found by age group and age (continuous variable), the students were apparently younger (median age = 20, IQR = 19–22 years old) than non-students (median age = 25, IQR = 22–31). Other studies found that younger MSM were less likely to have been tested for HIV, probably because of their fear of testing in healthcare or local office settings [26, 27]. Of note, this subgroup (young MSM and/or students) could be a targeted population for HIV prevention and control. This is because sexual behaviors such as group sex and having sex for money among students were not lower than non-students in our study (statistical results not shown). In addition, among those underwent HIV testing, adolescent and those with lower education level were more likely to be HIV positive (self-reported). It is possible that online intervention could reach a group of undiagnosed young adults living with HIV in China. With low post-intervention testing rate among students, other types of testing interventions such as school-based interventions may be needed to complement online intervention.

Our analysis has several limitations. Frist, this secondary analysis study did not allow us to prove the causal relationship between pre- and post-intervention HIV testing, and between testing intention and post-intervention testing action. However, the significant association of pre- and post-intervention testing intention with post-intervention testing action could show some linkage. Second, the sample size of this study was relatively small for performing a multilevel model nested by provinces, and therefore variables of ethnicity and IPV were excluded in the multilevel models. Third, like most other MSM studies, we used convenience sampling for recruiting MSM online as the overall sampling frame was unknown. Even though the internet is not limited by spatial distance, the coverage of recruited men was higher in the province hosting the website portal, which might introduce selection bias. We used multilevel models to account for possible heterogeneity. Fourth, HIV testing and test results were self-reported, which could not be validated. However, we believe that the social desirability bias was low because there was no additional incentive for undergoing HIV testing. We also used participants’ mobile phone numbers to prevent duplicate responses.

Conclusions

The proportion of intent to test of never-tested men rose from 46% at baseline to 62% after mass media intervention, with HIV testing reported by 36% at follow-up. Men who intended to test before and after intervention were more likely to test at follow-up. Men with high risk sexual behaviors, IPV experience and STI testing experience had higher preference for HIV testing. However, as student MSM were less likely to undergo testing even after intervention, further research is needed to enhance HIV testing and explain why adolescents were more likely to be HIV positive once tested. Possible future interventions include online tools complemented by conventional school-based interventions.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- MSM:

-

Men who have sex with men

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

References

Cohen MS, Chen Y, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda N, Brum T, Grinsztejn B et al: Final results of the HPTN 052 randomized controlled trial: antiretroviral therapy prevents HIV transmission. In: IAS 2015 8th conference on HIV pathogenesis, treatment and prevention. Vancouver, Canada; 2015: 9.

Zou H, Hu N, Xin Q, Beck J. HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1717–28.

National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: 2015 China AIDS Response Progress Report. In. Beijing, China; 2015.

Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Bulterys M, Chen RY: Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 151(4):241–251, w-252.

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Plan for HIV/AIDS prevention and control among men who have sex with men in China, 2007–2010. In.

UNAIDS: 90–90–90 - an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. In. Switzerland; 2014.

Muessig KE, Bien CH, Wei C, Lo EJ, Yang M, Tucker JD, et al. A mixed-methods study on the acceptability of using eHealth for HIV prevention and sexual health care among men who have sex with men in China. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(4):e100.

Wei C, Herrick A, Raymond HF, Anglemyer A, Gerbase A, Noar SM. Social marketing interventions to increase HIV/STI testing uptake among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender women. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011:CD009337.

Tso LS, Tang W, Li H, Yan HY, Tucker JD. Social media interventions to prevent HIV: a review of interventions and methodological considerations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;9:6–10.

World Health Organization: WHO l Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. In.; 2015: 193.

Guy R, Goller J, Leslie D, Thorpe R, Grierson J, Batrouney C, et al. No increase in HIV or sexually transmissible infection testing following a social marketing campaign among men who have sex with men. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:391–6.

Darrow WW, Biersteker S. Short-term impact evaluation of a social marketing campaign to prevent syphilis among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:337–43.

McOwan A, Gilleece Y, Chislett L, Mandalia S. Can targeted HIV testing campaigns alter health-seeking behaviour? AIDS Care. 2002;14(3):385–90.

Han L, Tang W, Best J, Zhang Y, Kim J, Liu F, Mollan K, Hudgens M, Bayus B, Terris-Prestholt F et al: Crowdsourcing to spur first-time HIV testing among men who have sex with men and transgender individuals in China: a non-inferiority pragmatic randomized controlled trial. In: 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention (IAS 2015). J Int AIDS Soc 2015, 18(5 Suppl 4):20479.

Tang W, Han L, Best J, Zhang Y, Mollan K, Kim J, et al. Crowdsourcing HIV test promotion videos: a Noninferiority randomized controlled trial in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(11):1436–42.

Zhang Y, Kim JA, Liu F, Tso LS, Tang W, Wei C, et al. Creative contributory contests (CCC) to spur innovation in sexual health: two cases and a guide for implementation. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;

Davis A, Best J, Wei C, Luo J, Van Der Pol B, Meyerson B, et al. Social entrepreneurship for sexual Health Research G: intimate partner violence and correlates with risk behaviors and HIV/STI diagnoses among men who have sex with men and men who have sex with men and women in China: a hidden epidemic. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(7):387–92.

Bekker LG, Hosek S: HIV and adolescents: focus on young key populations: J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(2Suppl 1):20076. doi:10.7448/IAS.18.2.20076.

Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, Beckman A, Johnell K, Hjerpe P, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:290–7.

Vidanapathirana J, Abramson MJ, Forbes A, Fairley C. Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing: Cochrane systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:233–4.

Yao J, Agadjanian V, Murray AT. Spatial and social inequities in HIV testing utilization in the context of rapid scale-up of HIV/AIDS services in rural Mozambique. Health & Place. 2014;28:133–41.

Zhao Y, Zhang L, Zhang H, Xia D, Pan SW, Yue H, et al. HIV testing and preventive services accessibility among men who have sex with men at high risk of HIV infection in Beijing. China Medicine. 2015;94:e534.

Guadamuz TE, Cheung DH, Wei C, Koe S, Lim SH. Young, online and in the dark: scaling up HIV testing among MSM in ASEAN. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126658.

Dunkle KL, Wong FY, Nehl EJ, Lin L, He N, Huang J, et al. Male-on-male intimate partner violence and sexual risk behaviors among money boys and other men who have sex with men in shanghai. China Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(5):362–5.

Tran A, Lin L, Nehl EJ, Talley CL, Dunkle KL, Wong FY. Prevalence of substance use and intimate partner violence in a sample of a/PI MSM. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(11):2054–67.

Mitchell JW, Horvath KJ: Factors associated with regular HIV testing among a sample of US MSM with HIV-negative main partners. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2013, 64:417–423.

Marcus U, Gassowski M, Kruspe M, Drewes J. Recency and frequency of HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Germany and socio-demographic factors associated with testing behaviour. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:727.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants and contest organizers. We would like to thank Dr. Kevin Fenton, the SESH Steering Committee, for guidance on contest implementation and Dr. Lai Sze Tso for the comments on the manuscript. We also thank the support of Ms. Jennifer Walker for the literature search. Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences at the Chinese University of Hong Kong is acknowledged for providing technical support in conducting the research.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the NIH Fogarty International Center Grant #5R25TW009340, R01 grant (NIAID 1R01AI114310–01), University of North Carolina CFAR #2 P30-AI50410, and the School of Medicine Dean’s Office at the University of California-San Francisco. Also from R00 grant (NIMH R00MH093201), the UNC-South China STD Research Training Center (FIC1D43TW009532–01), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the MeSH Consortium (BMGF-OPP1120138).

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials would be available upon application to the Chinese IRB and the University of North Caroline at Chapel Hill IRBs.

Authors’ contributions

JDT and WT motivated and designed the study. LH, JB and YZ conducted the survey. NSW analyzed the data. NSW, JDT and SWP interpreted the results. NSW wrote the article. JDT, BY, HZ, SH and CW oversaw the whole study process. JDT, SWP, CW, BY, HZ, SH and LH critically reviewed the article. All the authors reviewed and edited the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. A co-author, Dr. Joseph Tucker, is a member of the editorial board (Section Editor) of BMC Infectious Diseases.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approvals were obtained from the ethics review committees in Guangdong Provincial Center for Skin Diseases and STI Control, China, and from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of California, San Francisco, USA. Consent was obtained from each participant before starting the online survey.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Study layout. (PDF 170 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, N.S., Tang, W., Han, L. et al. MSM HIV testing following an online testing intervention in China. BMC Infect Dis 17, 437 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2546-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2546-y