Abstract

Background

Scant information is available on the infectious causes of febrile illnesses in Armenia. The goal of this study was to describe the most common causes, with a focus on zoonotic and arboviral infections and related epidemiological and clinical patterns for hospitalized patients with febrile illnesses of infectious origin admitted to Nork Infectious Diseases Clinical Hospital, the referral center for infectious diseases in the capital city, Yerevan.

Method

A chart review study was conducted in 2014. Data were abstracted from medical charts of adults (≥18 years) with a fever (≥38 °C), who were hospitalized (for ≥24 h) in 2010–2012.

Results

Of the 600 patients whose charts were analyzed, 76 % were from Yerevan and 51 % were male; the mean age (± standard deviation) was 35.5 (±16) years. Livestock exposure was recorded in 5 % of charts. Consumption of undercooked meat and unpasteurized dairy products were reported in 11 and 8 % of charts, respectively. Intestinal infections (51 %) were the most frequently reported final medical diagnoses, followed by diseases of the respiratory system (11 %), infectious mononucleosis (9.5 %), chickenpox (8.3 %), brucellosis (8.3 %), viral hepatitis (3.2 %), and erysipelas (1.5 %). Reviewed medical charts included two cases of fever of unknown origin (FUO), two cutaneous anthrax cases, two leptospirosis cases, three imported malaria cases, one case of rickettsiosis, and one case of rabies. Engagement in agricultural activities, exposure to animals, consumption of raw or unpasteurized milk, and male gender were significantly associated with brucellosis.

Conclusion

Our analysis indicated that brucellosis was the most frequently reported zoonotic disease among hospitalized febrile patients. Overall, these study results suggest that zoonotic and arboviral infections were not common etiologies among febrile adult patients admitted to the Nork Infectious Diseases Clinical Hospital in Armenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Armenia, located in the South Caucasus region, has an estimated population of 2.9 million [1]. Approximately 65 % of the population lives in urban areas, and the literacy rate among adults is almost 100 %. The country is divided into 11 regional government areas called marzes (ten regions plus Yerevan, the capital city) [2]. In Armenia, the National Center of Disease Control and Prevention (NCDCP), under the supervision of the Ministry of Health (MoH), is responsible for the control and prevention of communicable and noncommunicable diseases [3]. The NCDCP also develops and implements disease control policies and conducts epidemiological and environmental research to monitor and identify harmful factors that may affect the health of the population.

Available literature indicates that Q fever, plague, and sandfly fever were reported in Armenia in the late 1970s [4]. According to the NCDCP, the mortality rate from infectious and parasitic diseases in Armenia decreased from 12.4 deaths per 100,000 persons in 1990 to 9.2 in 2009 [5]. Unpublished MoH data indicates that acute respiratory infections and enteric infections were the main infectious diseases reported in Armenia during 2012–2013. During this period, 446, 30, and 2 cases of brucellosis, anthrax, and tularemia, respectively, were reported. The annual incidence rate of brucellosis was seven cases per 100,000 persons, with most cases occurring in the southern parts of Armenia and in rural areas adjacent to the neighboring country of Georgia. In 2006, a large entomological survey (64,567 mosquitoes and 45,180 Ixodes ticks), conducted by the Armenian Institute of Epidemiology, Virology, and Medical Parasitology, identified 125 distinct strains of arboviruses, including West Nile fever virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus [6]. In recent years, several studies have reported that endemic and emerging zoonotic infections, such as anthrax, leptospirosis, leishmaniasis, brucellosis, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, and hantavirus infection, are circulating in the South Caucasus region [7–13]. Despite the growing evidence suggesting that Armenian residents may be exposed to these zoonotic infections, little is known about the probable causes of febrile illness in the country. Therefore, a chart review study was undertaken to obtain information on the etiology, epidemiology, and clinical features among febrile patients admitted to the Nork Infectious Diseases Clinical Hospital. The Nork Hospital is the main referral center for pediatric and adult infectious diseases located in Yerevan, the capital city.

Methods

The study population was composed of hospitalized febrile patients admitted to the Nork Hospital between January 2010 and December 2012. Medical charts of inpatients with the following characteristics were eligible and selected for data abstraction: 1) 18 years of age or older; 2) fever (axillary temperature ≥38 °C) at hospital admission; and 3) hospitalization for at least for 24 h.

For this study, a standardized questionnaire was developed based on the medical charts used at the Nork Hospital. To describe the study population, questions on demographic, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics were developed. Information on exposure history and factors that influence the risk of transmission of zoonotic and arboviral infections were also collected through the questionnaire. The questionnaire was initially developed in English, and then translated into Armenian. The Nork Hospital study team extracted data from the medical charts to complete the questionnaires, which were then sent to the NCDCP for data entry and analysis. For data entry quality control, 20 % of the questionnaires were double-entered, compared, and reconciled. In addition, we ensured that values for study variables were within the response range and conducted a database consistency check.

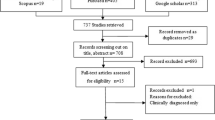

For sample size calculation, the Nork study team indicated that, of the 5000–6000 patients admitted to the hospital annually, approximately 250–300 patients met inclusion criteria. A convenience sampling of 600 medical charts over the study period (200 charts per year) were selected for data extraction, analysis, and reporting. In order to study seasonal variations or other changes over time, we extracted (where available) on average the first 20–35 charts per month that met the study criteria.

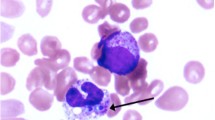

The following microbiological laboratory assays were used for diagnosis during the study period: Wright and Huddleston as well as Rose–Bengal serologic assays for brucellosis; commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for leptospirosis, hepatitis C, B and A viruses (HCV, HBV, HAV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), B. anthracis, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV); agglutination assay was available for Rickettsia spp. Blood culture was conducted routinely for fever of unknown origin (FUO) cases and when bacteremia was suspected. In addition to the above-mentioned serologic assays, bacteriological and molecular polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were used to isolate B. anthracis culture and detect genetic material of the bacteria from the skin swab sample. Chickenpox and rabies was diagnosed based on the clinical manifestation combined with the supportive epidemiological information. Malaria was diagnosed based on the thick and thin blood smear microscopy. ELISA and bone marrow biopsy sample microscopy were used in case of suspected leishmaniasis. Bacteriological investigations of stool were conducted, and immunoenzyme assays and microscopy were used to diagnose bacterial, viral, and parasitic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, PCR was available for HSV-1 and −2, HBV, HCV, EBV, CMV, as well as for Toxoplasma gondii.

Statistical analyses were carried out using Epi Info version 3.5.6 and the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 19. The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision was used to code and classify medical diagnoses registered in patient charts. Maps were created using the GIS program ArcMap version 10.1, the geographic projected coordinate system, and WGS 1984 Universal Transverse Mercator Zone 38°N.

This study protocol was approved by institutional review boards at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (FY13-20), Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR #2098), and the Yerevan State Medical University covering Armenian institutions.

Results

Of the 600 reviewed medical charts from hospitalized febrile patients at the Nork Hospital between 2010 and 2012, 51 % were males and the average age was 35.5 years (median = 30 years; Table 1). The majority of the patients were Armenian citizens (97 %), and 76 % were from Yerevan (Fig. 1). Patients from other regions (marzes) were admitted to the Nork Hospital, but to a lesser extent: Gegharkunik (5 %), Aragatsotn (4 %), Kotayk (3.9 %), Ararat (3.7 %), and Armavir (2.5 %). Most of the patient medical charts (78 %) did not register occupation; students comprised almost half (48 %) of those with known occupation. Of the reviewed charts, 71 % of the hospitalizations occurred between April and December.

Risk factor exposures for zoonotic and arboviral infections were not commonly recorded in the medical charts (Table 2). Based on available data, 5 % of the patients indicated that they had participated in agricultural activities, 4 % reported cattle exposure, and 1 % reported sheep exposure. Eight percent of the patients reported consumption of raw and unpasteurized milk products, and 11 % reported eating undercooked meat products. The percentage of patients who reported contact with a family member or with someone outside of the family with similar signs and symptoms before hospital admission was 11 and 15.2 %, respectively. Contact with water from rivers and ponds and visiting forests were rarely reported.

Based on the inclusion criteria, all patients in our study population had fever. Fatigue (97 % of patients), diarrhea (55 %), nausea/vomiting (54 %), and shaking/rigors (52 %) were the most frequently reported clinical signs and symptoms. Fewer than 5 % of the patients reported skin lesions, pain behind the eyes, unusual bleeding, or neck stiffness. As to the physical examination findings, pallor (51 %), abdominal tenderness (43 %), pharyngeal injection (43 %), and lymphadenopathy (35 %) were the most common (Table 3). Other physical findings—including edema, jaundice, mental status change, joint effusions, conjunctival infection, skin lesions, neurological findings, bleeding, neck stiffness, and heart murmur—were reported in fewer than 5 % of the charts.

Almost one-quarter (24 %) of the patients were treated with antibiotics before admission to the Nork Hospital, being ceftriaxone (27.8 %), chloramphenicol (16 %), and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (13.2 %) the antibiotics most commonly used. Antibiotic treatment was initiated at the Nork Hospital in 79.5 % (n = 477) of the patients, with ciprofloxacin (66 %) the most commonly used antibiotic. Of the patients treated with antibiotics at the hospital, 20 and 5 % of them received a combination of two and three antibiotics, respectively. Overall, the mean duration of hospitalization was 5.5 days. Few patients (n = 36; 6 %) had any complications during hospitalization.

With regard to final medical diagnoses (Table 4), intestinal infectious diseases (50.8 %) were the most commonly reported, followed by diseases of the respiratory system (11.2 %), infectious mononucleosis (9.5 %), chickenpox (8.3 %), brucellosis (8.3 %), and viral hepatitis (3.2 %). For purposes of reporting, the remaining diagnoses—malaria (n = 3), cutaneous anthrax (n = 2), leptospirosis (n = 2), fever of unknown origin (FUO, n = 2), rabies (n = 1), and rickettsiosis (n = 1)—were grouped into the category “Other”.

Brucellosis

In our study population, brucellosis was the fifth most frequently reported medical diagnosis. Of the 50 brucellosis cases, 37 (74 %) were in patients aged 18–47 years (Table 5). All of these patients first sought care at the Nork Hospital. We also found that brucellosis cases and non-brucellosis cases differed significantly by gender (p <0.0001) but not by age group (p = 0.449). The male-to-female ratio among brucellosis cases was 5 to 1; most cases were from the cities of Yerevan (28 %), Aragatsotn (20 %), Gegharkunik (16 %), and Kotayk (12 %). Of the patients with brucellosis, most (76 %) were diagnosed between the months of March and October.

At hospital admission, all patients with brucellosis had fever and fatigue. Other signs and symptoms also reported among brucellosis patients were excessive sweating (89 %), shaking (68 %), and joint pain (66 %). Brucellosis and non-brucellosis patients differed significantly on excessive sweating, muscle soreness, and joint pain (all p <0.0001). As to risk factors, consumption of raw or unpasteurized milk products, engagement in agricultural activities, exposure to animals, and participation in the slaughter of animals were significantly associated with brucellosis (Table 5).

Discussion

In this chart review study, we found that most adult patients admitted to the Nork Hospital between January 2010 and December 2012 were Yerevan residents. We believe that the low percentage of patients from other regions (marzes) is probably because they sought medical care at their local healthcare facilities during the study period. In contrast, the high percentage of patients from Yerevan’s neighboring marzes (Kotayk, Gegharkunik, Ararat, and Aragatsotn) is due to the geographic proximity of these marzes to the capital city. The association between geographic proximity and healthcare seeking has been reported in other settings [14, 15].

Information on risk factor exposure for zoonotic and arboviral infections was very limited in the medical charts. Despite this limitation, one-quarter of the hospitalized febrile patients reported having had contact with someone—whether a family member or other individual—with similar signs or symptoms before admission. This finding suggests that direct, person-to-person contact or exposure to common infection sources may influence the transmission of diseases in Armenia. Infectious respiratory and intestinal diseases are among those that can be transmitted via person-to-person contact; for common zoonotic infections, such as brucellosis, the existence of another case of brucellosis in the home is an important risk factor for infection [16, 17]. Additional investigation is required in Armenia to determine the multiple sources for disease exposure and routes of transmission for emerging zoonotic infections.

In our hospitalized febrile population, the most commonly reported signs and symptoms were frequently observed among patients with acute enteric diseases [18]. We found that slightly more than half of hospitalized febrile patients were diagnosed with intestinal infectious diseases at the Nork Hospital during the study period. Our analysis did not reveal any association of specific signs and symptoms with other diagnoses also found in this chart review, such as respiratory tract infections, infectious mononucleosis, brucellosis, chickenpox, and viral hepatitis. Additionally, the frequencies of these diagnoses were similar across the study period (data not shown).

According to the medical charts, the most common zoonotic infection reported was brucellosis. Other infections, such as malaria, leptospirosis, cutaneous anthrax, rickettsial infection, rabies, and rat-bite fever were reported to a lesser extent. A diagnosis of FUO was also recorded in two hospitalized patients. Our findings indicate that these emerging and reemerging infectious diseases are circulating and are, to some extent, recognized by the healthcare system in Armenia. It is possible that the incidence and diversity of zoonotic and arthropod vector-borne infections are higher in rural regions of the country, where agricultural practices, as well as ecological and climatic conditions, offer an environment favorable for disease transmission. A recent study conducted in the Turkey–Armenia border area reported the presence of multiple mosquito species that are potential vectors of several pathogens [19]. Our findings may not represent the full diversity and burden of the zoonotic and arthropod vector-borne diseases in Armenia. Both limited laboratory capacity for these infections at the Nork Hospital as well as the geographic distribution of the cases—the majority of hospitalized patients in this chart review were Yerevan residents—might have had an influence on our results.

The male-to-female ratio, age, and gender distribution of brucellosis cases were similar to those reported in Georgia, a neighboring country [20]. Limited data indicate that the seasonal pattern of brucellosis found in our study, with hospital admissions peaking during March–August, was similar to the pattern reported in the 1960s in Armenia [21]. As to clinical findings, the most prevalent signs and symptoms (excessive sweating, joint pain, and muscle soreness) were also reported among brucellosis patients in Georgia, Iran, Yemen, and Tanzania [8, 20–23]. Additionally, the identified risk factors for brucellosis, such as engagement in agricultural activities, exposure to animals, and consumption of raw or unpasteurized milk, were consistent with those published elsewhere [8, 20–23].

Data from a large animal study indicated that high-risk areas for brucellosis transmission are the South and along the western and northwestern border of Armenia [24]. Most brucellosis patients in our study were from two areas not considered high risk: the cities of Yerevan and Aragatsotn, a province in western Armenia, 18 km from Yerevan. Therefore, it is likely that patients from high-risk brucellosis areas received medical attention in regional care centers. All brucellosis patients in our study were hospitalized for the first time; thus, data on relapses or chronic debilitating complications associated with brucellosis were not available from the medical charts. Additional brucellosis studies in high-risk areas are required for a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiology of this infection and its impact on population health in Armenia.

In Armenia, malaria was completely eradicated in 1963, but reemerged in the 1990s [25]. Data from the World Malaria Report indicate that the number of malaria cases significantly decreased between 1998 and 2005 [26]. After successful efforts to control and interrupt disease transmission—which included long-lasting insecticidal nets, insecticides, and better diagnostic techniques—the World Health Organization declared Armenia malaria free by the end of 2011 [27]. The three Plasmodium falciparum malaria cases (all of them males) found in our febrile population were imported cases from Africa. This fact shows that malaria-free countries should include, as a component in their strategic plans, coordinated efforts with endemic countries to control imported malaria as recommended by subject matter experts [28].

According to Nork Hospital statistics, 11 (37 %) of the confirmed cutaneous anthrax cases reported in Armenia during 2012–2013 received care at the hospital (unpublished data). Of these, six anthrax cases were hospitalized during our study period, but only two of them were eligible for study inclusion (the other four did not have a fever on admission). In the past, anthrax cases also occurred in the Shirak region (western Armenia) in 2001, and Kotayk and Gegharkunik in 2006. In March 2013, a confirmed case of skin anthrax was reported in a patient who had previously slaughtered cattle in a Georgian village [29].

Armenia had one case of rabies in the late 1990s [30]. According to national statistics data, one rabies case and eight leptospirosis cases were registered during 2009–2010 [31]. In this study, the patient diagnosed with rabies was a 36-year-old male who was admitted to the Nork Hospital in October 2011. The first human leptospirosis case documented in Armenia was registered in Aykadzor, a town in northwestern Armenia, in 1948 (unpublished data). Since then, sporadic outbreaks have occurred in Armenia, most of them in the western part of the country. The two leptospirosis patients found in this study were a 56-year-old male and a 49-year-old female, both admitted to the hospital in May–June 2010.

Since 1950, human cases of spotted fever group rickettsiosis (SFGR) have been reported in Armenia, and evidence from human and tick molecular studies suggests that SFGR is circulating in the country [5, 32]. The 58-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with rickettsiosis in this study was a resident of Armavir, a region in the western part of Armenia.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that intestinal infectious diseases were the main causes of febrile illness, accounting for about one-half of hospital admissions; infections of the respiratory tract, infectious mononucleosis, and chickenpox together comprised approximately one-third of hospital admissions. Among zoonotic infections, brucellosis was the most frequently reported, followed by other emerging and reemerging diseases, such as rabies, rickettsiosis, leptospirosis, and anthrax. Although this study filled gaps in knowledge regarding the causes of febrile illness among hospitalized patients in the Nork Hospital, further integrated, prospective hospital- and population-based clinical and ecological research studies are required to provide more detailed information on the epidemiology of zoonotic and arthropod vector-borne diseases in Armenia.

Abbreviations

FUO, fever of unknown origin; GIS, Geographic Information System; MoH, Ministry of Health; NCDCP, National Center of Disease Control and Prevention; SFGR, spotted fever group rickettsiosis; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences; WGS, World Geodetic System; YSMU, Yerevan State Medical University

References

World Population Review: Armenia Population. 2014. [http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/armenia-population/]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia. Marzes (Regions) of the Republic of Armenia in Figures 1998–2002. Yerevan. 2003. [http://www.armstat.am/file/article/marz_03_0.pdf]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Wuhib T, Chorba TL, Davidiants V, Mac Kenzie WR, McNabb SJ. Assessment of the infectious diseases surveillance system of the Republic of Armenia: an example of surveillance in the Republics of the former Soviet Union. BMC Public Health. 2002;2:3.

Tarasević IV, Plotnikova LF, Fetisova NF, Makarova VA, Jablonskaja VA, Rehácek J, et al. Rickettsioses studies. 1. Natural foci of rickettsioses in the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;53(1):25–30.

International Finance Corporation: Study of the Introduction of the risk-based inspection system in the national hygiene and anti-epidemiological surveillance inspection. Yerevan. 2010. [http://www.mineconomy.am/up/files/hakahamacharakayin_teschutyun-143.pdf]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Manukian DV, Oganesian AS, Shakhnazarian SA, Aleskanian IT. The species composition of mosquitoes and ticks in Armenia. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2006;(1):31–3.

Kuchuloria T, Imnadze P, Chokheli M, Tsertsvadze T, Endeladze M, Mshvidobadze K, et al. Viral hemorrhagic Fever cases in the country of Georgia: acute febrile illness surveillance study results. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(2):246–8.

Havas KA, Ramishvili M, Navdarashvili A, Hill AE, Tsanava S, Imnadze P, et al. Risk factors associated with human brucellosis in the country of Georgia: a case-control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(1):45–53.

Kracalik I, Malania L, Tsertsvadze N, et al. Human Cutaneous Anthrax, Georgia 2010–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(2):261–4.

Mamuchishvili N, Kuchuloria T, Mchedlishvili I, Imnadze P. Leptospirosis in Georgia. Georgian Med News. 2014;(228):63–6.

Kuchuloria T, Clark DV, Hepburn MJ, Tsertsvadze T, Pimentel G, Imnadze P. Hantavirus infection in the Republic of Georgia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1489–91.

Zakhashvili K, Tsertsvadze N, Chikviladze T, Jghenti E, Bekaia M, Kuchuloria T, et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in man, Republic of Georgia, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(8):1326–28.

Babuadze G, Alvar J, Argaw D, de Koning HP, Iosava M, Kekelidze M, et al. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Georgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2725.

Al-Mandhari A, Al-Adawi S, Al-Zakwani I, Al-Shafaee M, Eloul L. Impact of geographical proximity on health care seeking behaviour in Northern Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2008;8(3):310–8.

Arcury TA, Gesler WM, Preisser JS, Sherman J, Spencer J, Perin J. The effects of geography and spatial behavior on health care utilization among the residents of a rural region. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):135–55.

Sacri AS, De Serres G, Quach C, Boulianne N, Valiquette L, Skowronski DM. Transmission of acute gastroenteritis and respiratory illness from children to parents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):583–8.

Sofian M, Aghakhani A, Velayati AA, Banifazl M, Eslamifar A, Ramezani A. Risk factors for human brucellosis in Iran: a case-control study. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:157–61.

Arena C, Amoros JP, Vaillant V, Ambert-Balay K, Chikhi-Brachet R, Jourdan-Da Silva N, et al. Acute diarrhea in adults consulting a general practitioner in France during winter: incidence, clinical characteristics, management and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:574. doi:10.1186/s12879-014-0574-4.

Aldemir A, Bedir H, Demirci B, Alten B. Biting activity of mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Turkey-Armenia border area, Ararat Valley, Turkey. J Med Entomol. 2010;47(1):22–7.

Akhvlediani T, Clark DV, Chubabria G, Zenaishvili O, Hepburn MJ. The changing pattern of human brucellosis: clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and treatment outcomes over three decades in Georgia. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:346.

Aleksanyan. Epidemiological geography of Armenian SSR. 1962. Tbilisi. [Dissertation thesis in Russian].

Al-Shamahy HA, Whitty CJ, Wright SG. Risk factors for human brucellosis in Yemen: a case control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125(2):309–13.

John K, Fitzpatrick J, French N, Kazwala R, Kambarage D, Mfinanga GS, et al. Quantifying risk factors for human brucellosis in rural northern Tanzania. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9968.

Porphyre T, Jackson R, Sauter-Louis C, Ward D, Baghyan G, Stepanyan E. Mapping brucellosis risk in communities in the Republic of Armenia. Geospat Health. 2010;5(1):103–18.

Avetisian LM. Epidemiological surveillance of parasitic diseases in the republic of Armenia. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2004;(1):21–4.

WHO 2009. World malaria report. [http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2009/en/]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

WHO. Malaria. Country Work. Armenia. [http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/vector-borne-and-parasitic-diseases/malaria/country-work/armenia]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Cotter C, Sturrock HJ, Hsiang MS, Liu J, Phillips AA, Hwang J, et al. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: new strategies for new challenges. Lancet. 2013;382(9895):900–11.

PamArmenianet. [http://www.panarmenian.net/eng/news/150648]. Accessed15 June 2015.

World Survey of Rabies No. 34 for the year 1998. [http://www.who.int/rabies/resources/en/wsr98_a12.pdf]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Stephen Berger. Leptospirosis. Global Status. 2014. [https://books.google.ge/books?id=lX93BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15&dq=Armenia+Leptospirosis&source=bl&ots=Ak6dw38wm1&sig=Qd2r7qIRCW5uUmwcY4PsP1lLChs&hl=ka&sa=X&ei=TKX1VPXcAcL8UvOUhMgO&ved=0CCAQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Armenia%20Leptospirosis&f=false]. Accessed 15 June 2015.

Eremeeva M, Balayeva N, Roux V, Ignatovich V, Kotsinjan M, Raoult D. Genomic and proteinic characterization of strain S, a Rickettsia isolated from Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks in Armenia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(10):2738–44.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the hard work and dedication of multiple host-country investigators. The authors thank Sebastian-Santiago and Lyudmila Niazyan for technical assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, within the U.S. Department of Defense under project TAP-H1. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of the Defense, the U.S. Government, or any organization listed. Some authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties and, as such, there is no copyright to be transferred.

Availability of data and materials

Data cannot be shared because relevant approvals from participating institutions are not in place.

Authors’ contributions

LP, VB, and KP were involved in study design, database development, data entry, data analysis, and data interpretation. EZ, ZG, VA, HA, and AH were involved in study design, questionnaire design, data abstraction, and final data interpretation. RR, CB, and TK contributed to the study design, data analysis, and data interpretation. All authors have actively participated in the development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for this retrospective chart review study was reviewed by the WRAIR, USAMRIID and YSMU IRBs. All engaged IRBs granted a “Research Not Involving Humans Subjects” determination for the activities under the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Paronyan, L., Zardaryan, E., Bakunts, V. et al. A retrospective chart review study to describe selected zoonotic and arboviral etiologies in hospitalized febrile patients in the Republic of Armenia. BMC Infect Dis 16, 445 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1764-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1764-z