Abstract

Background

Unplanned care interruption (UCI) challenges effective HIV treatment. We determined the frequency and risk factors for UCI in Nigeria.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective-cohort study of adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) between January 2009 and December 2011. At censor, patients were defined as in care, UCI, or inactive. Associations between baseline factors and UCI rates were quantified using Poisson regression.

Results

Among 2,496 patients, 44 % remained in care, 35 % had ≥1 UCI, and 21 % became inactive. UCI rates were higher in the first year on ART (39/100PY), than the second (19/100PY), third (16/100PY), and fourth (14/100PY) years (p < 0.001). In multivariate analysis, baseline CD4 > 350/uL (IRR 3.21, p < 0.0001), being a student (IRR 1.95, p < 0.0001), and less education (IRR 1.58, p = 0.001) increased risk for UCI. Fifty-five percent of patients with UCI and viral load data had HIV viral load > 1,000 copies/ml upon return to care.

Discussion

UCI were observed in over one-third of patients treated, and were most common in the first year on ART. High baseline CD4 count at ART initiation was the greatest predictor of subsequent UCI.

Conclusions

Interventions focused on the first year on ART are needed to improve continuity of HIV care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV is now a treatable, chronic disease with the availability of potent ART [1]. Accordingly, the strategic focus guiding the global HIV response has transitioned from acute crisis to chronic disease management [2]. Retention in care over time has plagued HIV treatment programs worldwide, particularly those in resource-limited settings (RLS) [3–5].

Retention in care requires a commitment to a package of clinical care including clinic appointments, laboratory visits, medication pick-up, and medication adherence. The early literature on retention in HIV care indicates startling rates of patient loss to follow-up (LTFU) in RLS, approaching 70 % prior to ART initiation and 25-40 % after ART initiation [5, 6]. Because many of these patients (15-90 %) are later found to have died, LTFU has been equated with disengagement from the entire package of HIV care [6–9].

It is now clear that patients defined as lost to follow-up represent many types of patients; some die, some voluntarily withdraw from care, others transfer care to different treatment facilities, while others interrupt but later return to care [10–15]. Patients with unplanned care interruptions (UCI) are at increased risk for CD4 decline, uncontrolled viremia, opportunistic infections, and long-term mortality [11, 13, 15–18].

The largest review of interruptions in care and treatment among HIV-infected patients highlights that such interruptions are common, occurring in approximately 25 % of patients initiated on ART [15]. This review also describes wide variation in definitions of care interruption ranging from 1 day to 1 year or more without treatment or care [15]. Risk factors for UCI in HIV care vary in different settings, however studies in RLS remain sparse [11, 15, 16, 19]. Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, and has the second largest HIV-infected population, behind South Africa [20, 21]. Our objective was to determine the rates and risk factors for UCI among patients who have initiated ART in Nigeria.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital’s (ABUTH) HIV clinic. ABUTH is located in a semi-urban community in the northern Nigerian state of Kaduna, HIV prevalence in the state is 9.2 % [20, 22]. The ABUTH clinic began providing care in 2006. In the same year, PEPFAR support commenced and ART was provided free of charge to all eligible patients. ABUTH currently offers comprehensive HIV testing and treatment to nearly 4,000 patients. During the study period, the clinic was managed by the AIDS Prevention Initiative in Nigeria (APIN), a PEPFAR-supported NGO, which is one of the largest HIV treatment programs in Nigeria.

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of ART eligible patients ≥14 years of age enrolled in the ABUTH clinic, who initiated ART between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2011. Patients were followed through December 31, 2012 to allow for a minimum of 1-year of observation for all patients. Women who were pregnant at enrollment or became pregnant during the follow-up period were not included in the analysis, as the protocol for clinic follow-up differed between this group and the general adult population. Upon clinic enrollment, patients received a variety of services according to protocol including clinical evaluation, TB symptom screening, adherence counseling, and CD4 count as well as viral load testing. Information on receipt of adherence counseling was not available in the electronic medical record. In the first 12 weeks after enrollment, patients were scheduled to be seen at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks for adherence counseling, clinical examination, and TB symptom screening. Subsequently, they were seen for ART pick-up every 4 weeks, clinical examination and adherence counseling every 12 weeks, and laboratory testing (including CD4 count and HIV viral load) every 24 weeks [23]. All data, including baseline demographic information, clinical visits and evaluations, laboratory visits and results, and drug pick-up visits were collected in structured data entry forms which were uploaded to APIN’s central electronic clinical database.

Outcome measures

At study censor date (December 31, 2012) we categorized patients into 1 of 3 mutually exclusive groups based on their visit patterns. A visit was defined as any encounter with the clinic, whether for clinical, laboratory, or pharmacy services. Patients were defined as in care if the time between any two consecutive visits was ≤90 days, and the time between the last visit and censor date was ≤180 days. Patients were defined as having an unplanned care interruption (UCI) if the time between any two consecutive visits was ever >90 days, but they returned to clinic before the censor date. This definition was not dependent upon the time between the last visit and censor date. Finally, patients were defined as inactive if the time between any two consecutive visits was ≤90 days, but the time between the last visit and the censor date was >180 days. Patients known to have transferred care or died during the follow-up period were categorized based on their visit patterns prior to transfer or death (i.e., such patients could not have been classified as inactive). Under routine circumstances, an absence from the clinic of at least 90 days implied that a patient missed three ART pick-up visits, and at least one clinical visit. In select circumstances, clinic protocol permitted dispensing of 2-month ART prescriptions to virologically suppressed patients on ART for >1 year. We chose a 90-day window to define UCI to ensure no overlap with this select group of stably suppressed patients.

Statistical analysis

Rates of UCI and time on ART

We determined the ratio of the number of patients with at least one UCI in the first, second, third, and fourth years on ART; and the total person-time at risk for UCI during each year. We calculated rates of UCI at the end of each year on ART.

Predictors of UCI in the first year on ART

We built bivariate and multivariate Poisson regression models to assess the association between baseline age, sex, education, employment, TB diagnosis, CD4 count, and enrollment year on the rate of first UCI during the first year on ART. We focused the analysis on predictors of UCI in the first year on ART since other studies have linked early missed visits to mortality, and to ensure consistent follow-up time for all patients in the analysis [13, 16, 18]. Additionally, we recognized that patients with UCI early after ART initiation might be different from those who interrupt later; our goal was to investigate predictors of the former. Data were censored at the date of last visit (before first UCI or becoming inactive from clinic) or one year after ART initiation for those who remained in care. Covariates with associations at p ≤ 0.10 in the bivariate model were included in the final multivariate model. The multivariate model was adjusted for enrollment year to account for possible temporal trends that might impact UCI.

Change in CD4 count before and after UCI

We conducted a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test on available CD4 counts drawn at baseline, prior to UCI, and within 3 months of return from UCI for patients who interrupted care.

HIV viral load after UCI

We reported dichotomized viral loads within 3 months of return from UCI (>1000 copies/mL vs. ≤1000 copies/mL) for patients who interrupted care and had available data; baseline HIV viral load testing is not routinely performed in this population.

Statistical analysis was conducted with Stata Statistical Software (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX, USA).

Sensitivity analysis

There is substantial variation in how absences from HIV care are defined in the literature [15, 24]. Consequently, we varied the definition of UCI from 90 days to 180 days without clinic contact in sensitivity analysis.

IRB approval

IRB approval was obtained from Partners HealthCare and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, MA, USA, and the Nigerian Institute for Medical Research in Lagos, Nigeria.

Results

Description of cohort

Our cohort was composed of 2,496 adults who enrolled at ABUTH and initiated ART between 2009 and 2011. Median observation time was 22.5 months [IQR 10, 36], and total person-years accrued during follow-up was 4,717. Females made up 69 % of the cohort and the median age was 32 years [IQR 27, 39]. Many patients (60 %) were married, and a large majority (77 %) had at least primary education. Sixty-three percent of patients were employed, 29 % were unemployed or retired, and 8 % were students. Sixty-two percent of patients presented with WHO stage 3 or 4 disease, and median baseline CD4 count was 207 cells/uL3 [IQR 98, 344] prior to ART initiation. Four percent of patients had TB upon enrollment (Table 1).

Twenty-four percent (n = 490/2029) of patients in the cohort (with available baseline CD4 values) enrolled and initiated ART with CD4 > 350 cells/uL. We conducted a chart review to determine the reasons for ART initiation in this group. All were documented to have met national guideline criteria for starting ART. The indication for treatment was advanced WHO stage (3 or 4) in 36 %, continuation of ART for patients previously treated in 20 %, concomitant TB in 5 %, and co-infection with Hepatitis B virus in 3 % of patients. The indication for ART initiation was not documented in 36 % of patients.

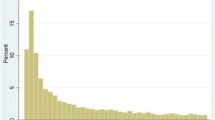

Patterns of care

At the end of follow-up, 44 % (n = 1,091) of patients remained continuously in care, 35 % (n = 867) had ≥1 UCI, and 21 % (n = 538) became inactive. Data about documented clinic transfers revealed that 4 % (n = 42) of patients who were in care, and 3 % (n = 31) of patients with UCI later transferred out of the clinic. Of the patients with UCI, 66 % (n = 576) had one interruption, 23 % (n = 198) had 2 interruptions, and 11 % had ≥3 interruptions (Fig. 1). UCIs lasted a median of 132 days [IQR 102, 205] before return to clinic. Patients remained in care a median of 114 days from enrollment before the first interruption in care [IQR 24, 364], and a median of 95 days [IQR 30, 238] before becoming inactive. We observed the highest rate of UCI in the first year on ART (39/100 PY, 95 % CI: 36–42). This decreased by more than half in the second year on ART (19/100 PY, 95 % CI: 17–21.0) and continued to decline in the third (16/100 PY, 95 % CI: 13–19) and fourth (15/100 PY, 95 % CI: 11–20) years on ART (Fig. 2).

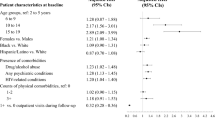

Factors associated with UCI in the first year on ART

In bivariate analysis, demographic characteristics associated with increased rate of UCI were being single (IRR 1.28, p = 0.007), having no education (IRR 1.21, p = 0.080), or primary/secondary education (IRR 1.22, p = 0.031) compared to tertiary education, and being a student (IRR 1.46, p = 0.007). Each decade increase in age was associated with a 15 % decreased risk of UCI (IRR 0.85, p < 0.0001). Patients who enrolled in clinic with CD4 count >350 cells/μL had an increased risk of UCI (IRR 3.30, p < 0.0001). Baseline CD4 count was lowest in the patients who later became inactive [median 172 cells/μL, IQR: 74, 289], and highest in those who later had interrupted care [median 272 cells/μL, IQR: 144, 436]. The risk of UCI did not significantly change with enrollment year (Table 2).

We conducted a multivariate analysis including variables significant in the bivariate analyses. A total of 467 patients (19 %) were excluded from the multivariate analysis due to unknown baseline CD4 count (158/632 with and 309/1864 without a care interruption). A further 33 patients (1 %) were excluded due to missing values for other variables in the model. In this analysis, having a high baseline CD4 count (>350 cells/μL) was associated with the greatest risk of UCI in the first year on ART (IRR 3.21, p < 0.001). Students (IRR 1.95, p < 0.0001) and patients with no education (IRR 1.58, p = 0.001) or primary/secondary education (IRR 1.39, p = 0.005) remained at increased risk for UCI in the multivariate model. While not statistically significant, there appeared to be a trend towards reduced risk of UCI among patients who enrolled in care in 2011 compared to those who enrolled in 2009 (IRR 0.08, p = 0.061) (Table 2).

The study results remained robust to different definitions of UCI (ranging from 90 to 180 days with no clinic contact) and inactive care (ranging from 90 days to 365 days between study censor date and last visit date).

Immunologic and virologic response among patients with unplanned care interruption

Baseline CD4 counts were available for 77 % (n = 667) of all patients with UCI and follow up CD4 values were available for 82 % of patients after first UCI. Two-thirds of CD4 counts were within 3 months of return to care. Among patients with UCI with CD4 data available median CD4 count increased from 255 cells/μL [IQR 136, 429] at baseline to 358 cells/uL [IQR 185, 511, n = 590], (p < 0.0001) before the first UCI and decreased to 329 cells/μL within 3 months of return to clinic [IQR 194, 487, n = 459], (p = 0.0001). Viral load data was available for 72 % (n = 620) of patients with UCI, nearly half were within 3 months of return to care. Fifty-five percent of viral loads obtained within 3 months of return to care were >1000 copies/mL.

Discussion

Missed visits from HIV clinic resulting in interruptions in HIV care, particularly in the first year on ART, are known to be a predictor of subsequent morbidity and mortality [13, 15, 16, 18]. In our study of almost 2,500 patients who started ART in Nigeria, nearly 1 in 4 had UCI, and another 1 in 5 became inactive from clinic. We found that patients who started ART with high baseline CD4 count had a greater than three-fold increased risk of UCI. Students, 72 % of whom were university matriculates, had a 2-fold increase in UCI. Additionally patients with less than tertiary education had a 50 % increased risk of UCI. More than half of patients with UCI for whom we had viral load data returned to clinic with virologic failure, as evidenced by viral load >1000 copies/mL.

There is a brief window of opportunity for clinics to identify and intervene on behalf of patients at increased risk for poor outcomes due to missed visits. We found that patients were generally in care for only 3 to 4 months before having an UCI. Furthermore, 12 % of patients with UCI in this cohort later became inactive from clinic. While a systematic review of data from Sub-Saharan Africa has shown that overall attrition rates are highest in the first year on ART, we believe this study is among the first to document that UCI is also greatest in the first year on ART (39/100 person-years) [6]. In our analysis, this rate declined by more than half after the first year on ART. Concomitant with high rates of interruptions in care, multiple studies from resource-limited settings also describe higher early mortality among patients on ART compared to patients in resource-rich environments [25–28]. These findings together underscore the importance of a rigorous focus on early, effective retention in care for patients initiating ART.

Our data did showed a possible trend towards improvement in the risk of UCI over time in the context of local and national efforts to improve retention. Nigeria’s 2010 National HIV guidelines called for “creation of effective linkage and retention mechanisms to maximize benefits of HIV treatment and care,” but did not provide specific recommendations for programs [23]. In 2011, the APIN network instituted a patient tracking protocol at all of its comprehensive sites, including ABUTH. APIN’s protocol calls for a multidisciplinary outreach team to identify patients after they miss a single clinic visit, contact them by telephone or home visit to determine the reason for the missed visit, and schedule a return visit. Additional follow-up is necessary to determine the impact of interventions such as these on retention and UCI.

Both feeling well and feeling unwell have been implicated as reasons for poor clinic attendance and LTFU in resource-limited settings [14, 15, 29]. Approximately 25 % patients in our cohort were initiated on ART with baseline CD4 > 350 cells/μL. Only 28 % of those were stably in care during the follow-up period; 54 % had interrupted care, and 18 % became inactive. These patients had a variety of indications for initiating ART, including advanced WHO stage, baseline TB, and concomitant hepatitis B virus infection. Nonetheless, adjusting for other demographic factors and time on ART, this group still had the greatest risk of UCI. In a systematic review of cohorts in Sub-Saharan Africa, between 31 % and 95 % of patients who have not yet met criteria to initiate ART are retained in care between enrollment in care and becoming ART eligible [5]. These patients would by definition have CD4 counts above current guidelines for ART initiation. They may feel well, and be less invested in care. Some programs have developed pre-ART care packages to improve retention in this group [23, 30]. Our findings, however, highlight poor retention even among patients with high CD4 counts who have already initiated ART. This has important implications for retention efforts as HIV treatment programs operationalize guidelines for ART initiation at higher CD4 thresholds, and some are calling for “test and treat” models regardless of CD4 count [31–34].

Several studies have shown increased risk of LTFU among single patients relative to their married counterparts [35–37]. In our analysis, single patients were at increased risk for UCI in bivariate, but not multivariate analysis. While it is possible that single patients may have less reliable support systems, and may be at greater risk for stigma and disruptions in care, ethnographic studies show that the relationship between social networks, stigma, and disclosure are complex [38]. Some studies highlight the importance of social networks and social capital to help mobilize resources for and commitment to care and treatment [39, 40]. On the other hand, a study from Malawi found that 74 % of patients who defaulted from care had not disclosed their HIV status to anyone in the household [29]. Other studies have underscored the challenges with trust, communication, discrimination and stigma faced by patients in both sero-concordant and sero-discordant relationships, often making it difficult to look to a marital or sexual partner for consistent adherence support [41–43]. These studies and others suggest that the promise of social support is balanced by fear of being ostracized morally, economically, and socially [38, 44].

We also identified a novel patient group, students, at greater risk for inconsistent care. Nearly 3 in 4 students in our cohort had UCI or became inactive from the clinic. At least 1 in 10 Nigerian youth are enrolled in secondary or tertiary educational programs [45]. This age group (15–29 year-olds) has the highest prevalence of HIV infection, and accounts for nearly one-third of Nigeria’s population [46, 47]. While there is a growing body of literature suggesting poorer treatment outcomes and retention among HIV-infected adolescents compared to their adult counterparts, the student population has received little attention [48, 49]. In our analysis, age was not a significant predictor of UCI in the first year on ART, even when categorized to compare adolescents to young and older adults. Many reasons may contribute to inconsistent care among students, including challenges in transitioning from home to school, adjustment to new HIV care providers (for those infected prior to starting university schooling), absence of a trusted support system, and frequent disruptions in the academic schedule by faculty and staff strikes in Nigeria [50, 51]. During these strikes, students may leave the campus for weeks or months to return home or to other family or friends [51]. Understanding barriers to care for students is an important next step to ensure successful clinical outcomes for this group.

The obstacles to consistent care may be different between resource-limited and resource-rich environments. In our study patients with less than tertiary-level education had a substantial increase in their risk of UCI. In a country with 23 % unemployment, it is likely that tertiary education is a proxy not only for formal education, but also or greater individual or household resources [52]. In Nigeria and other resource-limited settings, ART pick-up is tied directly to the clinic. While the medications themselves may be free, the cost of getting to the clinic or pharmacy and competing priorities have been identified as sometimes insurmountable challenges to effective adherence to care [53–55]. In our cohort, 93 % of all clinical encounters involved ART pick-up. In contrast, in the United States and other well-resourced environments, patients often have the option to retrieve ART prescriptions at pharmacies with convenient hours located close to home, or delivered directly to the home. Ninety percent of Americans live within five miles of a community pharmacy [56]. One qualitative study investigating reasons for interruptions in care in Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda described a level of unpredictable chaos that routinely disturbs patients’ plans and schedules [12]. The authors characterized this chaos as one of the unintended reasons for UCI. One consideration to reduce this obstacle is more flexible ART dispensation (>30 days) to reduce the burden of clinic visits earlier in the course of ART. In APIN programs, longer ART prescriptions may be made available, but typically only to patients who are stable on ART with continued virologic suppression after one year.

This study has several limitations. The cohort reflects one hospital-based clinic site in Nigeria, which may not be fully generalizable to other regions in Nigeria or other resource-limited settings. Because of the retrospective design, we were not able to assess reasons for UCI, including whether some temporarily transferred care, or to assess outcomes among patients who became inactive from clinic. Follow-up CD4 count and viral load values were available for only a subset of patients, and thus our estimates of immunologic and virologic consequences of interrupted care may be biased. We did not have information about which patients received ongoing adherence counseling, nor did we have full data about patient deaths, and thus could not assess the relationship between unplanned care interruption and these factors.

This analysis also has several strengths. It is one of the first African studies outside of South Africa to identify predictors of unplanned interruptions from HIV care. The study was set in Nigeria, where 10 % of the global AIDS population resides [20]. Our analysis relied on the robust electronic database of APIN, which captures patient encounters within the clinic, laboratory, and pharmacy. We were therefore able to assess a range of clinic encounters to investigate rates and predictors of overall unplanned interruptions from HIV care. In addition, because we had documentation of ART pick-up from pharmacy records, we knew that missed pharmacy visits implied that patients were not taking ART dispensed from the ABUTH clinic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, patients with consistent, stable engagement in HIV care are in the minority in a large ART program in Nigeria. Within the first four months after initiating ART, more than half of patients interrupt care for 90 days or more or become inactive from clinic. Given the impact of missed visits on subsequent immunologic and virologic compromise, as well as mortality, it is important to understand the reasons for interruptions in care. In our cohort, less educated patients, students, and those with higher baseline CD4 count were at greatest risk. Interventions to improve retention in care focused on high risk patients early after ART initiation are urgently needed.

Abbreviations

- ABUTH:

-

Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital

- APIN:

-

AIDS Prevention Initiative in Nigeria

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- LTFU:

-

Loss to follow-up

- RLS:

-

Resource-limited settings

- UCI:

-

Unplanned care interruption

References

Palella Jr FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60.

PEPFAR. The US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Five-Year Strategy. Available at: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/133035.pdf. Accessed September 22 2015.

Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33.

Ekouevi DK, Balestre E, Ba-Gomis FO, Eholie SP, Maiga M, Amani-Bosse C, et al. Low retention of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in 11 clinical centres in West Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15 Suppl 1:34–42.

Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8(7), e1001056.

Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15 Suppl 1:1–15.

Bassett IV, Wang B, Chetty S, Mazibuko M, Bearnot B, Giddy J, et al. Loss to care and death before antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:135–9.

Bisson GP, Gaolathe T, Gross R, Rollins C, Bellamy S, Mogorosi M, et al. Overestimates of survival after HAART: implications for global scale-up efforts. PLoS One. 2008;3(3), e1725.

Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4, e5790.

Geng EH, Nash D, Kambugu A, Zhang Y, Braitstein P, Christopoulos KA, et al. Retention in care among HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: emerging insights and new directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):234–44.

Ahonkhai AA, Noubary F, Munro A, Stark R, Wilke M, Freedberg KA, et al. Not all are lost: Interrupted laboratory monitoring, early death, and loss to follow-up (LTFU) in a large South African treatment program. PLoS One. 2012;7(3), e32993.

Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Geng EH, Kaaya SF, Agbaji OO, Muyindike WR, et al. Toward an understanding of disengagement from HIV treatment and care in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1), e1001369.

Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):248–56.

Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, Emenyonu N, Bwana MB, Yiannoutsos CT, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(3):405–11.

Kranzer K, Ford N. Unstructured treatment interruption of antiretroviral therapy in clinical practice: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(10):1297–313.

Brennan AT, Maskew M, Sanne I, Fox MP. The importance of clinic attendance in the first six months on antiretroviral treatment: a retrospective analysis at a large public sector HIV clinic in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:49.

Zhang Y, Dou Z, Sun K, Ma Y, Chen RY, Bulterys M, et al. Association between missed early visits and mortality among patients of china national free antiretroviral treatment cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):59–67.

Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, Klein DB, Quesenberry CP, Mugavero MJ. Missed office visits and risk of mortality among HIV-infected subjects in a large healthcare system in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(8):442–9.

Mills EJ, Funk A, Kanters S, Kawuma E, Cooper C, Mukasa B, et al. Long-term health care interruptions among HIV-positive patients in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):e23–7.

The World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.DDAY. Accessed January 10 2014

UNAIDS. 2013 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf. Accessed January 15 2014.

National Agency for the Control of AIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, Nigeria. 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2014countries/NGA_narrative_report_2014.pdf. Accessed September 22 2015.

Federal Ministry of Health Nigeria. National Guidelines for HIV and AIDS Treatment and Care in Adolescents and Adults. 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/nigeria_art.pdf. Accessed September 22 2015.

Chi BH, Yiannoutsos CT, Westfall AO, Newman JE, Zhou J, Cesar C, et al. Universal definition of loss to follow-up in HIV treatment programs: a statistical analysis of 111 facilities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. PLoS Med. 2011;8(10), e1001111.

Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):817–24.

Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(15):1897–908.

Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT, Chandrasekhar A, Gupte N, Bisson GP, et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(12), e28691.

Kranzer K, Lewis JJ, Ford N, Zeinecker J, Orrell C, Lawn SD, et al. Treatment interruption in a primary care antiretroviral therapy program in South Africa: cohort analysis of trends and risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(3):e17–23.

McGuire M, Munyenyembe T, Szumilin E, Heinzelmann A, Le Paih M, Bouithy N, et al. Vital status of pre-ART and ART patients defaulting from care in rural Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15 Suppl 1:55–62.

Kohler PK, Chung MH, McGrath CJ, Benki-Nugent SF, Thiga JW, John-Stewart GC. Implementation of free cotrimoxazole prophylaxis improves clinic retention among antiretroviral therapy-ineligible clients in Kenya. AIDS. 2011;25(13):1657–61.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health apprach. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/. Accessed January 20 2014.

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Dodd PJ, Garnett GP, Hallett TB. Examining the promise of HIV elimination by 'test and treat' in hyperendemic settings. AIDS. 2010;24(5):729–35.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F, Boyer S, Lessells RJ, Lert F, et al. Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (Treatment as Prevention) trial in Hlabisa sub-district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:230.

Hassan AS, Fielding KL, Thuo NM, Nabwera HM, Sanders EJ, Berkley JA. Early loss to follow-up of recently diagnosed HIV-infected adults from routine pre-ART care in a rural district hospital in Kenya: a cohort study. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(1):82–93.

Bekolo CE, Webster J, Batenganya M, Sume GE, Kollo B. Trends in mortality and loss to follow-up in HIV care at the Nkongsamba Regional hospital, Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):512.

Mugisha V, Teasdale CA, Wang C, Lahuerta M, Nuwagaba-Biribonwoha H, Tayebwa E, et al. Determinants of mortality and loss to follow-up among adults enrolled in HIV care services in Rwanda. PLoS One. 2014;9(1), e85774.

Merten S, Kenter E, McKenzie O, Musheke M, Ntalasha H, Martin-Hilber A. Patient-reported barriers and drivers of adherence to antiretrovirals in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-ethnography. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15 Suppl 1:16–33.

Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(1), e11.

O'Laughlin KN, Wyatt MA, Kaaya S, Bangsberg DR, Ware NC. How treatment partners help: social analysis of an African adherence support intervention. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1308–15.

Rispel LC, Cloete A, Metcalf CA. 'We keep her status to ourselves': experiences of stigma and discrimination among HIV-discordant couples in South Africa, Tanzania and Ukraine. SAHARA J. 2015;12(1):10–7.

Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN. Perceived HIV-related stigma and HIV disclosure to relationship partners after finding out about the seropositive diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):415–32.

Stirratt MJ, Remien RH, Smith A, Copeland OQ, Dolezal C, Krieger D. The role of HIV serostatus disclosure in antiretroviral medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):483–93.

Nachega JB, Knowlton AR, Deluca A, Schoeman JH, Watkinson L, Efron A, et al. Treatment supporter to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected South African adults. A qualitative study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43 Suppl 1:S127–33.

Aluede O, Idogho PO, Imonikhe JS. Increasing access to university education in Nigeria: present challenges and suggestions for the future. The African Symposium. 2012;12(1):3–13.

UNICEF. Nigeria Information Sheet on HIV/AIDS 2007. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/wcaro/english/WCARO_Nigeria_Factsheets_HIV-AIDS.pdf. Accessed October 5 2013.

PEPFAR. Action Today, a Foundation for Tomorrow: 2006 Second Annual Report to Congress on PEPFAR. Available at: http://www.state.gov/s/gac/rl/c16742.htm. Accessed April 15 2014.

Evans D, Menezes C, Mahomed K, Macdonald P, Untiedt S, Levin L, et al. Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adolescents attending public-sector HIV clinics across Gauteng and Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(6):892–900.

Minniear TD, Gaur AH, Thridandapani A, Sinnock C, Tolley EA, Flynn PM. Delayed entry into and failure to remain in HIV care among HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(1):99–104.

University of Ilorin. Faculty of Education. Ilorin Journal of Education. In: Alabi AT, editor. Conflicts in Nigerian Universities: Causes and Management. Ilorin, Nigeria: Faculty of Education; 2002. p. 102–14.

Adesulu D. Incessant ASSU strikes: bane of education sector. Vanguard. Lagos, Nigeria: Vanguard Media; 2012.

National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria. Available at: http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng. Accessed March 20 2014.

Fox MP, Mazimba A, Seidenberg P, Crooks D, Sikateyo B, Rosen S. Barriers to initiation of antiretroviral treatment in rural and urban areas of Zambia: a cross-sectional study of cost, stigma, and perceptions about ART. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:8.

Harries AD, Zachariah R, Lawn SD, Rosen S. Strategies to improve patient retention on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15 Suppl 1:70–5.

Tuller DM, Bangsberg DR, Senkungu J, Ware NC, Emenyonu N, Weiser SD. Transportation costs impede sustained adherence and access to HAART in a clinic population in southwestern Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):778–84.

NACDS. NCPDP Pharmacy File, ArcGIS Census Tract File 2013. Available at: http://rximpact.nacds.org/pdfs/rximpact_0313.pdf. Accessed February 10 2014.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers: K23 AI106406-02, R01 AI058736-09S1, R01 MH090326, 2P30AI060354. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported in part by cooperative agreement number 5U2GPS001058 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study/analysis: AAA, KAF, EL. Analyzed the data. AAA, SR. Contributed analysis tools: AAA, BB, JA, KAF, EL, SR. Wrote the paper: AAA. Performed and/or oversaw primary data collection, provided guidance on the analysis plan: BB, JA, IO, PO. Edited the manuscript: AAA, JA, IO, IVB, EL, KAF, PO, SR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahonkhai, A.A., Banigbe, B., Adeola, J. et al. High rates of unplanned interruptions from HIV care early after antiretroviral therapy initiation in Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis 15, 397 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1137-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1137-z