Abstract

Background

Iatrogenic skin and soft tissue infections by rapidly growing mycobacteria are described with increasing frequency, especially among immunocompromised patients.

Case presentation

Here, we present an immunocompetent patient with extensive Mycobacterium fortuitum skin and soft tissue infections after subcutaneous injections to relieve joint pains by a Vietnamese traditional medicine practitioner. Moreover, we present dilemmas faced in less resourceful settings, influencing patient management.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the pathogenic potential of rapid growing mycobacteria in medical or non-medical skin penetrating procedures, their world-wide distribution and demonstrates the dilemmas faced in settings with fewer resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mycobacterium fortuitum is a member of the group of non-pigmented Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria (RGM), and is found ubiquitously in nature (soil, dust, and in tap water in biofilms), over a wide geographical area. Infections with non-tuberculous mycobacteria have been described increasingly, especially in immunocompromised patients and as iatrogenic infections in immunocompetent patients, causing a variety of local and disseminated disease. RGM in particular can cause local skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) and have also been described in outbreak and pseudo-outbreak settings involving infections after surgery or other invasive procedures [1]-[3]. Here, we describe a case from the Hospital of Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam of M. fortuitum infection of the skin and soft tissues covering several joints after injection of traditional Vietnamese medicine to relieve joint pain. We discuss the diagnostic process and treatment for this patient in a setting with fewer resources.

Case presentation

An immunocompetent, 61-year old female patient from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, was admitted to the Hospital for Tropical Diseases with multiple painful fluctuating and non-fluctuating masses on both hands and feet (see Figure 1) and on her back. She was also subfebrile (37.8°C). Her previous history was uneventful except for mild hypertension and a hysterectomy because of a benign tumour. For the past 2 years she experienced numbness in both hands and feet, which was the reason for consulting a Vietnamese traditional medicine practitioner 15 days prior to admission. For three consecutive days, the patient received an oral preparation, as well as multiple subcutaneous injections (at the metacarpophalangeal and metatarsophalangeal joints of the hands and feet, and at the shoulder and hip joints) with a red substance, both of unknown composition. Five days post-injection, the injection sites became erythematous, painful, and swollen. She developed a fever and was treated at a local clinic with unknown (antimicrobial) drugs without clinical improvement, after which she was admitted to our hospital.

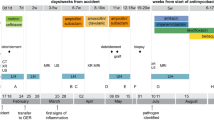

Top, left to right: pretreatment pictures of hands and feet at day 4 and during treatment at day 67, respectively. Bottom, left to right: two pictures of a Ziehl-Neelsen stain (1000X) of aspirated pus from the abscess on dorsal side of the patient’s right hand (acid-fast bacilli indicated with arrowheads), and a blood agar plate of aspirated pus showing non-pigmented dry colonies of Mycobacterium fortuitum after 4 days incubation (with two contaminating yellow colonies in the middle and bottom of the plate).

Laboratory findings showed: procalcitonin 0.083 ng/ml (reference range <0.05 ng/ml), leucocytes 14.8 • 103/μl (6-10 • 103/μl), neutrophiles 81.2% (reference range: 49-65.5%). Blood cultures (BactAlert; bioMérieux, France) were taken and empiric antimicrobial therapy was started with intravenous (i.v.) oxacilline to cover Staphylococcus aureus and group A beta-haemolytic streptococci.

A pulmonary X-ray, and X-ray imaging of hands and feet were unremarkable, and incision and drainage of the abscesses followed. Gram stains of the collected fluids showed slender beaded and fragmentally stained Gram positive rods, suggestive of mycobacteria. This was subsequently confirmed by Ziehl-Neelsen staining (see Figure 1). Because of reported sensitivity loss and the presence of nodules, leprosy was ruled out by investigation of ear lobe skin slits.

Based on microscopy results, a preliminary diagnosis of multiple mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) with rapidly growing mycobacteria was made, and treatment was initiated with oral clarithromycine (500 mg/b.i.d.) and intramuscular (i.m.) amikacin (500 mg/t.i.d.).

Purulent fluid was cultured on standard culture media (blood agar and McConkey agar) for three days and yielded grey wrinkled colonies on blood agar (no growth on McConkey agar) (see Figure 1), morphologically suspect of Mycobacterium spp. This was confirmed by Gram and ZN staining and the isolate was later genotyped as Mycobacterium fortuitum by 16S DNA PCR and sequencing analysis.

Initial drug susceptibility testing (DST) by disk diffusion on Müller-Hinton agar showed the strain to be resistant to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), azithromycin and tobramycin, but susceptible to amikacin, imipenem and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Clinical improvement during the 120-day admission was variable and slow, with subfebrile temperatures (38°C) last monitored on day 14, and the appearance of new fluctuating lesions on days 23 (hands/feet), 29 (hands/feet), 32 (right shoulder and hip), and 72 (shoulder), which were incised and drained. M. fortuitum was isolated again from the day-23 and day-29 samples, whilst microscopy and culture remained negative thereafter. Papules and blisters emerged at the sites of formerly drained sites on the hands/feet on day 72 and 80, and healed 5 days later; microbiological investigations were negative. From day 90 onwards, all lesions healed (see Figure 1), and no new skin and soft tissue abnormalities were observed.

Antimicrobial therapy was adjusted several times during admission based on repeated DST results and financial incentives. Empiric treatment was started with amikacin (i.m. 500 mg/t.i.d.) and oral clarithromycin (500 mg/b.i.d.). This was later changed to amikacin (i.m. 500 mg/t.i.d.), doxycycline (100 mg/b.i.d.) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole, 960 mg/b.i.d.), after culture results and pending additional DST. Imipenem, to which the isolate was susceptible but which the patient could not afford, was not given at this time. Once resistance to tetracyclines and co-trimoxazole were reported and amikacin had been administered for 14 days, therapy was adjusted to imipenem monotherapy i.v. 500 mg/t.i.d, and later (day 50) to imipenem 1 gram/q.i.d, based on international guidelines. Imipenem therapy was funded by the hospital. The patient was discharged on day 120, at which point imipenem was changed to oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (500/125 mg/t.i.d.), and follow-up visits transpired for 8 months. Antimicrobial treatment was stopped 4 months after discharge, while clinical improvement was observed 1 month after discharge (Table 1).

Our patient was not immunocompromised, as were 21/29 cases described by Lee et al., yet had extensive lesions which were spreading, even during therapy [4]. The number and location of lesions on initial presentation correlated with the received subcutaneous injections. Guevara-Patinos et al. describe M. fortuitum infection with multiple skin lesions after acupuncture. This was treated with doxycycline and ciprofloxacin for three months which led to full recovery [5]. Pai et al. describe a case of recurrent subcutaneous abscesses of unknown aetiology that did not respond to empiric antibiotic treatment and later was diagnosed as a M. fortuitum SSTI [6]. Because of side effects, this patient was eventually successfully treated with surgical excisions. The development of several new nodules/abscesses during antimicrobial therapy was worrisome in our case, as this could be indicative of failure of antimicrobial therapy due to misinterpretation of the susceptibility results, resistance development or dissemination in an ongoing extensive infection [7],[8]. The gold standard for susceptibility testing of RGM is the broth dilution method as described by the CLSI [8]. In our setting, broth dilution was unavailable. For imipenem an E-test was performed, for ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, tobramycin, azithromycin, co-trimoxazole, amikacin and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid disk diffusion was performed on Müller-Hinton agar.

Our patient’s treatment regimen was altered on many occasions, but overall, 105 days of imipenem monotherapy was prescribed, in addition to the 14 days of amikacin therapy and 4 months of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, for which the isolate was sensitive according to disk diffusion. After discharge and an 8 months follow-up period, she remained free of symptoms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, M. fortuitum and other RGM are not very pathogenic, but can cause infections after direct inoculation into sterile sites, e.g. trauma with skin damage, use of contaminated surgical instruments or fluid for injection or after use of contaminated tap water during invasive procedures [7]. Infections with M. fortuitum appear to occur in younger patients who are generally not immunocompromised, and manifest more often after surgical procedures [9]. M. fortuitum is more sensitive to antibiotics than the related M. abscessus or M. chelonae and infections have a better recovery rate [10]. In our case, the isolate was relatively resistant by disk diffusion tests and only susceptible to amikacin, imipenem and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. The patient clinically recovered after more than 12 weeks of antimicrobial therapy, which was continued for a total of 8 months. This case illustrates the pathogenic potential of RGM in medical or non-medical skin penetrating procedures and their world-wide distribution. Additional dilemmas faced in this setting with less resources were the limited availability of (biochemical) typing and susceptibility testing methods, of required antibiotics and of insurance coverage.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Authors’ contributions

NVVC and DHL were responsible for patient treatment, NPHL, NTT, JC and HRVD participated in the described diagnostic process, NVD and MEK collected data and information and drafted the report, HRVD finalized the manuscript, all authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

References

De Groote MA, Huitt G: Infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2006, 42 (12): 1756-1763. 10.1086/504381.

Wallace RJ, Swenson JM, Silcox VA, Good RC, Tschen JA, Stone MS: Spectrum of disease due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Rev Infect Dis. 1983, 5 (4): 657-679. 10.1093/clinids/5.4.657.

Cho SY, Peck KR, Kim J, Ha YE, Kang CI, Chung DR, Lee NY, Song JH: Mycobacterium chelonae infections associated with bee venom acupuncture. Clin Infect Dis. 2014, 58 (5): e110-e113. 10.1093/cid/cit753.

Lee WJ, Kang SM, Sung H, Won CH, Chang SE, Lee MW, Kim MN, Choi JH, Moon KC: Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin: a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Dermatol. 2010, 37 (11): 965-972. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00960.x.

Guevara-Patino A, de Mora M S, Farreras A, Rivera-Olivero I, Fermin D, de Waard JH: Soft tissue infection due to Mycobacterium fortuitum following acupuncture: a case report and review of the literature. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010, 4 (8): 521-525.

Pai R, Parampalli U, Hettiarachchi G, Ahmed I: Mycobacterium fortuitum skin infection as a complication of anabolic steroids: a rare case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013, 95 (1): e12-e13. 10.1308/003588413X13511609955175.

Esteban J, Garcia-Pedrazuela M, Munoz-Egea MC, Alcaide F: Current treatment of nontuberculous mycobacteriosis: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012, 13 (7): 967-986. 10.1517/14656566.2012.677824.

Kothavade RJ, Dhurat RS, Mishra SN, Kothavade UR: Clinical and laboratory aspects of the diagnosis and management of cutaneous and subcutaneous infections caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013, 32 (2): 161-188. 10.1007/s10096-012-1766-8.

Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, Virk A, Wilson JW: Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006, 142 (10): 1287-1292. 10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287.

Wallace RJ, Swenson JM, Silcox VA, Bullen MG: Treatment of nonpulmonary infections due to Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonei on the basis of in vitro susceptibilities. J Infect Dis. 1985, 152 (3): 500-514. 10.1093/infdis/152.3.500.

Acknowledgements

NVD, NTT and HRVD were funded by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain, grant 089276/Z/09/Z. JIC was supported by the European Union FP7 project “European Management Platform for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Disease Entities (EMPERIE)” (no. 223498). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, N.P.H., Kolader, ME., Van Dung, N. et al. Mycobacterium fortuitum skin infections after subcutaneous injections with Vietnamese traditional medicine: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 14, 550 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0550-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0550-z