Abstract

Introduction

The aging population is a challenge for the healthcare system that must identify strategies that meet their needs. Practicing patient-centered care has been shown beneficial for this patient-group. The effect of patient-centered care is called patient-centered outcomes and can be appraised using outcomes measurements.

Objectives

The main aim was to review and map existing knowledge related to patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcomes measurements for older people, as well as identify key-concepts and knowledge-gaps. The research questions were: How can patient-centered outcomes for older people be measured, and which patient-centered outcomes matters the most for the older people?

Study design

Scoping review.

Methods

Search for relevant publications in electronical databases, grey literature databases and websites from year 2000 to 2021. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full text review and extraction of data using a data extraction framework.

Results

Eighteen studies were included, of which six with involvement of patients and/or experts in the process on determine the outcomes. Outcomes that matter the most to older people was interpreted as: access to- and experience of care, autonomy and control, cognition, daily living, emotional health, falls, general health, medications, overall survival, pain, participation in decision making, physical function, physical health, place of death, social role function, symptom burden, and time spent in hospital. The most frequently mentioned/used outcomes measurements tools were the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT), EQ-5D, Gait Speed, Katz- ADL index, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9), SF/RAND-36 and 4-Item Screening Zarit Burden Interview.

Conclusions

Few studies have investigated the older people’s opinion of what matters the most to them, which forms a knowledge-gap in the field. Future research should focus on providing older people a stronger voice in what they think matters the most to them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Both the number and proportion of older people is increasing in most countries. In 2019, there were 703 million people aged 65 years and older in the world, corresponding to nine percent of the population, and estimates predict that this number will have doubled by 2050 [1]. An aging population is a challenge for the healthcare system [2], which was underscored by the coronavirus pandemic 2019 (COVID-19) [3]. Hence, the healthcare system needs to identify strategies to meet the needs of the growing proportion of older people in order to achieve a high quality of care [2], a central aspect of being the focus on patient-centered care and outcomes for older people [3].

The concept of patient-centered care was first introduced in the late 1980ies, and has come to gain impact on healthcare research [4]. The essence of patient-centered care can be captured by the question posed as “what matters to you?, rather than the more traditionally used, “what is the matter with you?”[5]. The patient-centered approach shifts the focus from clinical guidelines to the patient’s requests, experiences, and point of view – i.e. a shift of caring focus from healthcare-centered to patient-centered [5]. The effect of patient-centered care is patient-centered outcomes which can be measured by patient-centered outcome measurements [6]. There are to our knowledge no prior systematic reviews studying both patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcome measurements specific to older people.

Studies regarding patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcome measurements typically focus on a specific condition, disease, or event, such as stroke, bladder cancer, anemia or asthma [7,8,9,10]. Previous studies have focused on patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcome measurements in general [11,12,13], but few studies have focused on patient-centered outcomes and how to measure these for older people [14]. Old people often have complex needs [15] motivating a holistic, patient-centered approach [5]. Therefore, this review has focused on publications reflecting a general approach among unselected patient populations, i.e. not on specific conditions.

The aim of the current scoping review was to review and map the existing knowledge regarding patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcome measurements for people 65 years of age and above, representing an unselected patient population, as well as to identify key-concepts and knowledge-gaps.

Methods

Study design

The scooping review method was chosen as a form of knowledge synthesis to provide an overview of available knowledge in relation to the research questions: which patient-centered outcomes matter the most for older people? How can these patient-centered outcomes for older people be measured? [16].

Protocol and registration

A review protocol was established in accordance with the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [17], Levac et al. [18] and the Joanna Briggs Institute [16]. The review protocol was registered in April 2021 on the Open Science Framework (OSF) website [19].

Eligibility criteria

An initial exploratory search of publications relevant to the topic was conducted prior to the registration of the review protocol, and the results discussed in the research group. Based on the exploratory search, the following eligibility criteria were defined:

-

▪ Main topic/core concept of the publication: Patient-centered outcomes and/or patient-centered outcome measurements.

-

▪ Study context: A broad context was chosen to limit the risk of overseeing relevant evidence anywhere in the health care system.

-

▪ Study population: People aged 65 years and older. The age-limit was chosen since the cutoff age for older people in research commonly is 65 years and older [20, 21]. An unselected study population, i.e. no specific medical condition, since the aim was to investigate the population of older people in general, and not in relation to a given condition. Publications using the term “multimorbidity”, which is common among the study population of interest [15], were included.

-

▪ Type of publication: Peer reviewed original articles and systematic reviews.

-

▪ Time frame: From year 2000 to 2021.

-

▪ Language: English.

Exclusion criteria:

▪ Conference abstracts, book reviews, commentaries, and editorial publications.

▪ Publications that focus on a specific disease or event.

Search

The search strategy was developed and executed in collaboration with experienced librarians.

The full electronic search strategy for the database PubMed is shown in Appendix No 1. Grey literature was searched in databases and websites relevant to the topic. This was done in the same manner as for the electronic databases, however, the search strategy was adapted to the specific database or website and its search function.

Information sources

In 2021 a search for previous reviews related to the topic of patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcome measurements for older people was conducted in the databases PubMed and Joanna Briggs Institute. The search generated five systematic reviews of patient-centered care and patient-centered outcomes for older people [22,23,24,25,26] and three scoping reviews regarding patient-centered outcomes, however, not specific to older people [27,28,29].

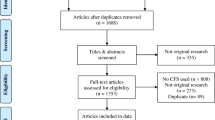

Relevant publications were searched in 2021 using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and EMBASE. Grey literature sources were searched in the databases Grey Literature Report and Open Grey and in the following websites: the “Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute” (pcori.org), the “Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality” (ahrq.gov) and “Patient Centered Outcomes Research” (pcor.org.uk). Removal of duplicates was performed by the librarian and the remaining publications were consolidated in the reference management software Covidence®. The reference lists of the initially included publications (n = 13) were hand searched to limit the risk of overlooking relevant publications. An additional five relevant publications were identified and included in Covidence (Fig. 1).

Selection of publications. Flowchart according to PRISMA [30]

Selection of publications

The review process consisted of two levels of screening. At first, two reviewers (LD, ÅA) independently screened publications for titles and abstracts in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Second, the publications of interest were read independently and reviewed in full text by the two reviewers, with application of the eligibility- and exclusion criteria. Disagreements regarding the eligibility of a publication were discussed and a third reviewer acted as an arbitrator (LK) when consensus was not reached.

Data extraction

The data extraction framework was developed prior to the registration of the review protocol, Appendix No 2. A pilot test on one of the included publications was performed to ensure consistent application of the data extraction framework. No revision of the data extraction framework was needed after the pilot test. The two reviewers independently extracted the data from the included publications using the data extraction framework. The data was compared between the two reviewers. Any differences in extracted data were discussed (LD and ÅA), and a third reviewer (LK) was consulted if consensus was not reached.

Data collection

Data was extracted in accordance with the data extraction framework, (Appendix No 2).

Synthesis of results

Data was reviewed and synthesized to obtain an accessible overview and to answer the research aims. Information from the included publications was synthesized using a pragmatic narrative approach in the following steps. First, the publications were categorized based on country of origin, year of publication, study design and context in the health care system. Secondly, patient-centered outcomes and outcome measurement tools were categorized based on the core concept of the outcome of the publication into the following categories: access to and experience of care, carer needs, cognition, daily living, emotional health, physical health, quality of life and others. Thereafter, an additional consolidation of results to present the most common expressions of what matters the most to the older people and how this can be measured is presented. Finally, the involvement of the study population was categorized based on study participants as: participation of older people, older people and experts and experts.

Results

Selection of sources of publications

Eighteen publications of the total of 4 222 publications were included. The identification and selection of publications is presented in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of included publications

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Appendix No 3 and include the information according to the data extraction framework (Appendix No 2) with the exception of study outcomes.

Results from included publications

Patient-centered outcomes, patient-centered outcome measurements and the involvement of the study population in the process of determining which outcomes to measure and which matters the most, are presented in Table 1.

Synthesis of results

Publication information

Over half of the publications were written in the USA, published after year 2010 and the most common context was the community setting. Several different study designs/methods were used. Information regarding the publications is summarized in Table 2.

Synthesis of patient-centered outcomes and outcome measurement tools

The following patient-centered outcomes were the most frequently mentioned: access to care, activities of daily living (ADL), care needs, carer burden, cognitive function, communication, depression, emotional well-being, health, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), medications, physical function, quality of care, quality of life and social activity. The most frequently mentioned measurement tools were the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT), EQ-5D, Gait Speed, Katz- ADL index, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9), SF/RAND-36 and 4-Item Screening Zarit Burden Interview.

Tables 3 and 4 present a synthesis of patient centered outcomes and measurement tools. The main categories were access to- and experience of care, carer needs, cognition, daily living, emotional health, physical health, and quality of life.

Study population and what matters the most

Older people were not involved in the process of determining which outcomes mattered the most and how to measure them in 12 of the 18 included publications. Three of the studies involved older people as participants, one used experts in the field as patient representatives, and two involved both older people and experts. The synthesis of the results showed that the outcomes that matter most to older people were: access to- and experience of care, autonomy and control, cognition, daily living, emotional health, falls, general health, medications, overall survival, pain, participation in decision making, physical function, physical health, place of death, social role function, symptom burden and time spent in hospital, (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The current scoping review aimed to explore the knowledge in the field of patient-centered outcomes and measurements for older people. The results showed that the outcomes that matter the most to older people were: access to- and experience of care; autonomy and control; cognition; daily living; emotional health; falls; general health; medications; overall survival; pain; participation in decision making; physical function; physical health; place of death; social role function; symptom burden; and time spent in hospital. The Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT), EQ-5D, Gait Speed, Katz- ADL Index, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9), SF/RAND-36 and 4-Item Screening Zarit Burden Interview were the measurement tools most frequently used to measure patient-centered outcomes for older people.

The patient-centered outcomes in the current review were consolidated into the main categories: access to- and experience of care, carer needs, cognition, daily living, emotional health, others, physical health, and quality of life. Researchers at the Picker Institute have described that patient-centered care is based on the following dimensions: respect for the patient´s values, preferences and expressed needs, information and education, access to care, emotional support to relieve fear and anxiety, involvement of family and friends, continuity and secure transitions between healthcare settings, physical comfort, and coordination of care [48]. Further, a NEJM Catalyst article has suggested the following dimensions; mission and values aligned with patient goals; care is collaborative, coordinated and accessible; physical comfort and emotional well-being are top priorities; patient and family viewpoint respected and valued; patient and family always included in decisions; family welcome in care setting; full transparency and fast delivery of information [49]. The dimensions of patient centered care as suggested by the Picker Institute and the NEJM Catalyst article capture the same dimensions and support the current results. However, the current review identifies an important knowledge gap, i.e. that there are few studies actually including the target population: the older people themselves, while experts tend to speak on their behalf. Therefore, the list of what matters the most to older people, as presented here, should be considered as indicative. Future studies should involve older people to be able to answer to the question of what matters most to this population.

Attending to an ageing population is and will continue to be a challenge for the healthcare system [2]. Our results present how patient-centered outcomes can be measured and indicate that personal domains such as daily living and quality of life seem to be linked with the patient’s experienced health and well-being. Patient-centered care has been shown to lower the need of high-level emergency care and the risk of mortality for older people with multimorbidity [5] as well as reducing healthcare costs in multiple settings [50,51,52]. Including older people in the design of health care organization and caring pathways is needed in addition to including older people in scientific studies.

Limitations

A strength of the study is the extensive literature search. A structured review has been carried out by two independent reviewers. A third reviewer was consulted if consensus was not reached. The major limitation is the inherent risk of limiting the literature search with the risk of not including relevant publications. An additional limitation is that the search strategy was not peer-reviewed. However, the search strategy was, in addition to the research team, developed in collaboration with experienced clinical librarians.

An additional limitation was the method used in the four steps of consolidation and results synthesis. A rigid method to analyze the level of evidence and further analyze the results was not applicable due to the limited number of publications which were included in the current study. Hence, a pragmatic, narrative approach was used.

Moreover, the search term “elderly” may be questioned, as the term old people has evolved to be the recommended terminology for the patient population of interest. However, this is a more recent development and we believe the results of the current study to be of interest despite this evolution.

Conclusions

Patient-centered outcomes for older people can be summarized in the categories: access to- and experience of care; carer needs; cognition; daily living; emotional health; others; physical health; and quality of life. Patient-centered outcomes can be measured using several different measurement tools. Outcomes that matter the most to older people were: access to- and experience of care, autonomy and control, cognition, daily living, emotional health, falls, general health, medications, overall survival, pain, participation in decision making, physical function, physical health, place of death, social role function, symptom burden, and time spent in hospital. Importantly, few studies included the older people as the study population, despite patient centered aims. Future research should focus on providing the older people with a stronger voice in what they think matters the most to them.

Availability of data and material

Inquiries for data access should be sent to the corresponding author, asa.andersson@oru.se, who will then contact the ethics board at Örebro University for permission to openly share the data.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily life

- ASCOT:

-

Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit

- BIMS:

-

Brief Interview for Mental Status

- CFS:

-

Clinical Frailty Scale

- CMAS:

-

Condensed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol 5 dimensions

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7

- GFI:

-

Groningen Frailty Index

- GWI:

-

Groningen Well-being Indicator

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities of daily living

- LiSat-11:

-

Life Satisfaction Questionnaire

- LSI:

-

Life Satisfaction Index -Z (LSI-Z)

- MDS:

-

Minimum Data Set assessments

- MMSE:

-

Mini Mental State Examination

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PAT:

-

Preferences Assesment Tool

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PROMIS-29:

-

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29-item Health Profile

- QUAL-E:

-

Quality of life at the end of life

- SF/RAND-36:

-

36 Item Short Form Survey

References

World population ageing 2019 (ST/ESA/SER.A/444) p. 1-3. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf.

Mahishale V. Ageing world: health care challenges. J Sci Soc. 2015;42(3):139.

Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219–25.

Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm J. 2012;16(3):49–53.

Berntsen GKR, Dalbakk M, Hurley JS, Bergmo T, Solbakken B, Spansvoll L, Bellika JG, Skrøvseth SO, Brattland T, Rumpsfeld M. Person-centred, integrated and pro-active care for multi-morbid elderly with advanced care needs: a propensity score-matched controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):2.

Helping measure person-centred care. Chapter. 5. Measurement tools. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/HelpingMeasurePersonCentredCare.pdf.

Xian Y, O’Brien EC, Fonarow GC, Olson DM, Schwamm LH, Hannah D, Lindholm B, Maisch L, Lytle BL, Greiner MA, et al. Patient-centered research into outcomes stroke patients prefer and effectiveness research: implementing the patient-driven research paradigm to aid decision making in stroke care. Am Heart J. 2015;170(1):36-45.e11.

Gore JL. Patient-centered outcomes in bladder cancer. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19(12):105.

Staibano P, Perelman I, Lombardi J, Davis A, Tinmouth A, Carrier M, Stevenson C, Saidenberg E. Patient-centered outcomes in the management of anemia: a scoping review. Transfus Med Rev. 2019;33(1):7–11.

Anise A, Hasnain-Wynia R. Patient-centered outcomes research to improve asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1503–10.

Ahmed S, Djurkovic A, Manalili K, Sahota B, Santana MJ. A qualitative study on measuring patient-centered care: Perspectives from clinician-scientists and quality improvement experts. Health Sci Rep. 2019;2:e140.

Winn K, Ozanne E, Sepucha K. Measuring patient-centered care: an updated systematic review of how studies define and report concordance between patients’ preferences and medical treatments. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(7):811–21.

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;70(4):351–79.

Akpan A, Roberts C, Bandeen-Roche K, Batty B, Bausewein C, Bell D, Bramley D, Bynum J, Cameron ID, Chen L-K, et al. Standard set of health outcome measures for older persons. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):36.

Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35(1):75–82.

Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Patient-centered outcomes and patient-centered outcomes measurements for elderly: a scoping review protocol. https://osf.io/mtg64/.

Österholm JH, Larsson Ranada Å. Characteristics of research with older people (over 65 years) in occupational therapy journals, 2013–2017. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(4):240–7.

Ouchi Y, Rakugi H, Arai H, Akishita M, Ito H, Toba K, Kai I, on behalf of the Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological S, Japan Geriatrics Society on the d, classification of the e. Redefining the elderly as aged 75 years and older: proposal from the Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(7):1045–7.

Ebrahimi Z, Patel H, Wijk H, Ekman I, Olaya-Contreras P. A systematic review on implementation of person-centered care interventions for older people in out-of-hospital settings. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(1):213–24.

Kogan AC, Wilber K, Mosqueda L. Person-centered care for older adults with chronic conditions and functional impairment: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):1–7.

Brownie S, Nancarrow S. Effects of person-centered care on residents and staff in aged-care facilities: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1–10.

de Jong MJ, Huibregtse R, Masclee AAM, Jonkers DMAE, Pierik MJ. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(5):648–63.

Preyde M, Brassard K. Evidence-based risk factors for adverse health outcomes in older patients after discharge home and assessment tools: a systematic review. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2011;8(5):445–68.

Kersting C, Kneer M, Barzel A. Patient-relevant outcomes: what are we talking about? A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):596.

Constand M, Macdermid J, Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271.

Poitras M-E, Maltais M-E, Bestard-Denommé L, Stewart M, Fortin M. What are the effective elements in patient-centered and multimorbidity care? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):446.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Shoup JA, McQuillan DB, Steiner JF, Zeng C. Association between continuity of care and health-related quality of life. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(2):205–12.

Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Shoup JA, Zeng C, McQuillan DB, Steiner JF. Association of patient-centered outcomes with patient-reported and ICD-9-based morbidity measures. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):126–33.

Bearon LB, Crowley GM, Chandler J, Robbins MS, Studenski S. Personal functional goals: a new approach to assessing patient-centered outcomes. J Appl Gerontol. 2000;19(3):326–44.

Berg AI, Hoffman L, Hassing LB, McClearn GE, Johansson B. What matters, and what matters most, for change in life satisfaction in the oldest-old? A study over 6 years among individuals 80+. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2):191–201.

Drouin H, Walker J, McNeil H, Elliott J, Stolee P. Measured outcomes of chronic care programs for older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(1):139.

Berglund H, Hasson H, Kjellgren K, Wilhelmson K. Effects of a continuum of care intervention on frail older persons’ life satisfaction: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(7–8):1079–90.

Hong SH, Liu J, Tak S, Vaidya V. The impact of patient knowledge of patient-centered medication label content on quality of life among older adults. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(1):37–48.

Kane AR, Lum YT, Cutler JL, Degenholtz BH, Yu T. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: a longitudinal evaluation of the initial green house program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:832–9.

Lee W-J, Peng L-N, Lin C-H, Lin S-Z, Loh C-H, Kao S-L, Hung T-S, Chang C-Y, Huang C-F, Tang T-C, et al. First insights on value-based healthcare of elders using ICHOM older person standard set reporting. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):335.

Lee H, Shi SM, Kim DH. Home time as a patient-centered outcome in administrative claims data: home time as a patient-centred outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(2):347–51.

Leff B, Sheehan OC, Harrison KL, Eaton England A, Mickler A, Basyal PS, Garrigues SK, Schuchman M, Perissinotto C, Garrett SB, et al. A home-based care research agenda by and for homebound older adults and caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(12):1715–21.

Roberts TJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Lor M, Liebzeit D, Crnich CJ, Saliba D. Important care and activity preferences in a nationally representative sample of nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(1):25–32.

Working Group on Health Outcomes for Older Persons with Multiple Chronic C. Universal health outcome measures for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(12):2333–41.

Shankar KN, Bhatia BK, Schuur JD. Toward patient-centered care: a systematic review of older adults’ views of quality emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(5):529-550.e521.

Stock R, Mahoney ER, Reece D, Cesario L. Developing a senior healthcare practice using the chronic care model: effect on physical function and health-related quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1342–8.

You EC, Dunt D, Doyle C, Hsueh A. Effects of case management in community aged care on client and carer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials and comparative observational studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):395.

Wald HL, Leykum LK, Mattison MLP, Vasilevskis EE, Meltzer DO. A patient-centered research agenda for the care of the acutely Ill older patient: research agenda for older patient care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):318–27.

Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet A-M. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):953–7.

What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559?targetBtn=articleToolSaveBtn.

Pirhonen L, Gyllensten H, Olofsson EH, Fors A, Ali L, Ekman I, Bolin K. The cost-effectiveness of person-centred care provided to patients with chronic heart failure and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Policy Open. 2020;1:100005.

Stewart M, Ryan BL, Bodea C. Is patient-centred care associated with lower diagnostic costs? Healthcare Policy. 2011;6(4):27–31.

Gyllensten H, Koinberg I, Carlström E, Olsson LE, Olofsson EH. Economic analysis of a person-centered care intervention in head and neck oncology: Hanna Gyllensten. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(Supplement 3):ckx187.336.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to all personnel at the University Library, Örebro University.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University. Open access funding provided by Örebro University. The study was partly founded by Region Örebro County, Sweden. Grant number OLL 961450.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design LD, ÅA and LK. LD and ÅA independently screened publications, LK acted as an arbitrator. ÅA, LD and LK have contributed scientifically, and contributed to the data analysis, drafting of the manuscript (LD) and manuscript revision (ÅA, LK). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, Å.G., Dahlkvist, L. & Kurland, L. Patient-centered outcomes and outcome measurements for people aged 65 years and older—a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 24, 528 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05134-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05134-7