Abstract

Background

Frailty is a pervasive clinical syndrome among the older population. It is associated with an increased risk of diverse adverse health outcomes including death. The association between sleep duration and frailty remains unclear. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between sleep duration and frailty in community-dwelling Korean older adults and to determine whether this relationship is sex-dependent.

Methods

Data on 3,953 older adults aged ≥ 65 years were obtained from the 7th (2016–2018) Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Frailty was defined using the Fried phenotype with criteria customized for the KNHANES dataset. Self-reported sleep duration was classified as short sleep duration (≤ 6 h), middle sleep duration (6.1–8.9 h), and long sleep duration (≥ 9 h). Complex samples multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The percentage of male participants with short, middle, and long sleep durations was 34.9%, 62.1%, and 16.8%, respectively, while that of female participants was 26.1%, 59.2%, and 14.7%. The prevalence of frailty in the middle sleep duration group was lower than that in the short and long sleep duration groups in both men (short, 14.7%; middle, 14.2%; long, 24.5%; p < 0.001) and women (short, 42.9%; middle, 27.6%; long, 48.6%; p < 0.001). Both short (OR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.91 − 4.83) and long (OR = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.36 − 3.88) sleep duration groups had a significantly higher OR for frailty than the middle sleep duration group even after adjusting for confounding variables among women, but not among men.

Conclusion

Short and long sleep durations were independently associated with frailty in community-dwelling Korean older adult women. Managing sleep problems among women should be prioritized, and effective interventions to prevent frailty should be developed accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to stressors that results from decreased physiological reserves and multisystem dysregulation, or a state of limited capacity to maintain homeostasis and respond to internal and external stresses [1]. In community-dwelling older adults, frailty is associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes including falls, disability, hospitalization, institutionalization, and death [2, 3].

The prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older adults varies widely depending on age, sex, and country. Although direct comparisons may be limited because of factors such as differences in frailty assessment methods, the prevalence of frailty in Korea (23.1%) is relatively higher than that in other countries such as the United States (7.1%), Japan (7.4%) and China (10.1%) [4,5,6,7]. Although the cause of frailty has not been fully identified yet, its prevalence increases with age. By 2050, the proportion of people aged ≥ 65 years in Korea is predicted to be 39.8% [8]. Frailty is an important public health issue for older adults in the aging Korean population owing to its prevalence and social burden. However, frailty is partially reversible and preventable [9, 10]. Therefore, a better understanding of the risk factors associated with frailty is crucial to develop new strategies for its prevention and management.

Appropriate sleep is crucial to the overall health and well-being of older adults. However, sleep disturbance is reportedly experienced by approximately 50% of this population [11, 12]. In Korea, 32.4% of older adults in the Korean community experience sleep disorders [13], and 61.8% do not sleep for the duration recommended by The National Sleep Foundation [14]. In addition, older adults with sleep problems may have a lower quality of life, cognitive decline, depression, and other adverse health outcomes including frailty [15].

Sleep disturbances and frailty often coexist and are interrelated, especially among older adults [16], and recent studies have shown that frailty is significantly associated with sleep duration among these individuals [17, 18]. While some studies [17, 19,20,21,22] have reported that long sleep duration was associated with a greater risk of frailty, others [23, 24] reported that short sleep duration was associated with frailty. However, some studies [21, 25] found that both long and short sleep durations were associated with frailty. In addition, the relationship between sleep duration and frailty is reportedly sex-dependent [5, 20, 23, 24]. Investigation of the relationship between sleep duration and frailty is crucial and essential for managing sleep problems and frailty among the Korean older adults. Nevertheless, only few studies have investigated this relationship community-dwelling Korean older adults [14, 20]. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the relationship between sleep duration and frailty in community-dwelling Korean older adults and to determine whether this association is sex-dependent. Based on existing literature, we hypothesized that individuals with a short or long sleep duration exhibit more severe frailty than those with a normal sleep duration among Korean older adults, and there are sex differences in the association between sleep duration and frailty after controlling for sociodemographic variables, lifestyle-related variables, and health-related variables.

Methods

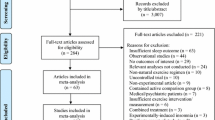

Study design and participants

This study used data from the 7th (2016 − 2018) Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). The KNHANES, conducted annually by the Korea Center for Disease Control (KCDC) and the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, is a nationwide population-based survey designed to assess the health-related behavior, health conditions, and nutritional status of Korean adults. The survey uses stratified, multistage, clustered probability sampling methods to select a representative sample of civilian non-institutionalized Korean adults (the plan, protocol, and survey license are available at http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr). The inclusion criteria for the current study were as follows: age ≥ 65 years and presence of relevant data. Of the 24,269 participants from the 7th KNHANES, we included 3,953 participants in the current analysis after excluding 19,313 participants aged < 65 years and 1,003 with missing data on frailty, sleep duration, and covariate variables. All participants provided written informed consent, and the survey collection process was approved by the KCDC Research Ethics Review Committee (Institutional Review Board number: 2018-01-03-P-A).

Assessment of sleep duration

The participants were queried about their usual times for the onset of sleep and waking. Self-reported sleep duration was calculated as the difference between these times. As previously described [18, 23], we classified participants into three groups according to their self-reported sleep duration: short ≤ 6 h, middle 6.1–8.9 h, and long ≥ 9 h.

Assessment of frailty

The outcome variable in this study was frailty, assessed as per a modified frailty phenotype developed by Fried et al. [3]: (1) unintended weight loss (self-reported; ≥3 kg in the past year) [26], (2) weakness (handgrip strength < 26 kg for men and < 18 kg for women based on the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2014) [27], (3) slowness (responded “I have slight difficulty walking” or “I have to stay in the bed all day” in at least one of two questions in the Euro Quality of life 5-Dimensions, a motor ability indicator) [28], (4) emotional exhaustion (responded “I feel considerably exhausted” to the level of stress awareness question) [29], and (5) low physical activity (< 2 h of moderate-intensity physical activity/week or < 1 h of high-intensity physical activity/week) [30]. Participants who met three or more criteria were classified as “frail,” one or two as “pre-frail,” and zero as “robust.”

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included sex (man/woman), age (65 − 69/70 − 74/75 − 79/≥80 years), education level (≤ 6 years/≥7 years), household income (lower/lower middle/upper middle/upper), living arrangement (alone/with family), and area of residence (urban/rural). Lifestyle-related variables included self-rated health status (good/poor), current smoking (yes/no), and current drinking (yes/no). Health-related variables included the number of chronic diseases (0/1 − 2/≥3), body mass index (BMI) (underweight/normal weight/overweight/obese), pain (yes/no), and limitation of daily life (yes/no). Chronic diseases included hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, diabetes mellitus, cancer (stomach, liver, colon, breast, cervical, and lung), and liver disease (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and cirrhosis). BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m2) and defined (according to the Korean guidelines and KNHANES recommendations) as follows: underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, 18.5–22.9 kg/m2; overweight, 23–24.9 kg/m2; and obese, ≥ 25 kg/m2 [31]. Limitation of daily life was evaluated using a questionnaire focused on daily life and social activities affected by health problems, physical disorders, or mental disorders.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Based on statistical guidance from the KCDC, we used a complex sample analysis method to utilize all weighted data from the KNHANES. Descriptive statistics were calculated as frequencies and percentages. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables among groups. Complex samples multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between sleep duration and frailty. Potential confounding factors, including age, education level, household income, living arrangements, area of residence, self-rated health status, smoking status, drinking status, number of chronic diseases, BMI, pain, and limitation of daily life, were adjusted for. Due to the significant sex differences in frailty, data from men and women were analyzed separately. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

The characteristics of the participants according to sleep duration stratified by sex are presented in Table 1. Among men, there were 375 (34.9%), 1,104 (62.1%), and 299 (16.8%) participants in the short, middle, and long sleep duration groups, respectively. All covariates differed among the three groups of different sleep durations, except for current smoking and the number of chronic diseases. While in women, there were 568 (26.1%), 1, 287 (59.2%), and 320 (14.7%) participants in the short, middle, and long sleep duration groups, respectively. There were differences in age, education, household income, area of residence, self-rated health, and limitation of daily life among the sleep duration groups. The prevalence rate of frailty in the middle sleep duration group was lower than that in the short and long sleep duration groups in both men (short, 14.7%; middle, 14.2%; long, 24.5%; p < 0.001) and women (short, 42.9%; middle, 27.6%; long, 48.6%; p < 0.001). These results were similar in each frailty component, except for unintended weight loss (Table 1).

The characteristics of the participants according to frailty status stratified by sex are presented in Table 2. Among men, there were 346 (19.4%), 1,141 (64.1%), and 291 (16.3%) participants in the robust, pre-frailty, and frailty groups, respectively, while in women, there were 188 (8.6%), 1,197 (55.0%), and 790 (36.3%). In men, all covariates differed among the three groups. In women, all covariates, except for the living arrangement, current smoking, and BMI, differed among the three groups (Table 2).

The associations of sleep duration with frailty and components of frailty were analyzed using complex samples multivariate logistic regression, after the control of age, education level, household income, living arrangement, area of residence, self-reported health status, smoking status, drinking status, number of chronic diseases, BMI, pain, and limitation of daily life. Multivariate analysis revealed that compared with the middle sleep duration group, the odds ratio (OR) for frailty were significantly higher in the short (OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.91 − 4.83) and long (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.36 − 3.88) sleep duration groups among women. This association was not observed in men.

According to each component, the long sleep duration group had a significantly higher OR for weakness (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.24 − 1.97) than the middle sleep duration group among men. In women, compared with the middle sleep duration group, the ORs for weakness (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.58 − 2.25) and exhaustion (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.02 − 1.78) were higher in the short sleep duration group, while the ORs for weakness (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.92 − 2.87) and low physical activity (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.36 − 3.09) were higher in the long sleep duration group (Table 3).

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that both short and long sleep durations were associated with frailty among women, but not among men. Particularly, short and long sleep durations had a higher OR for frailty than middle sleep duration, even in multivariate analysis after adjusting for age, education level, household income, living arrangement, area of residence, self-rated health status, smoking status, drinking status, number of chronic diseases, BMI, pain, and limitation of daily life.

Literature reports on the relationship between sleep duration and frailty, however, are inconsistent. A previous study [18] on 9,824 Japanese older adults aged 65 and above showed that both short (< 6 h) and long (≥ 9 h) sleep durations were associated with a higher frailty risk compared to middle sleep duration, extending to statistical analysis stratified by sex. A longitudinal study on Mexican older adults aged 70 and above showed that both short (< 6 h) and long (≥ 9 h) sleep durations were associated with frailty [21]. In another study, only short sleep duration (< 5 h or < 6 h) was associated with frailty among women, but not among men [23, 32]. On the contrary, other studies found that only long sleep duration (≥ 9 h or ≥ 10 h) was associated with frailty [19, 20, 22]. Kang et al. [20] reported that long sleep duration (≥ 8 h), but not short sleep duration (< 6 h), effectively explained frailty in older adult women aged 70 years or older in Korea. In addition, no association was observed between sleep duration and frailty in men. Interestingly, Zhang et al. [5] reported that long sleep duration (≥ 9 h) was associated with frailty in men, while short sleep duration (< 6 h) was associated with frailty in women, this indicated a sex-specific association.

These inconsistencies may be attributed to differences in the frailty measures, sleep duration assessment methods (self-reported vs. actigraphy), or sleep duration classifications (short sleep duration defined as < 5 h, < 6 h, or < 7 h), or due to sex disparity [19, 33]. The inconclusive results of these studies also raise the question of whether older adults in different countries or regions have different sleep requirements [22]. Disruptions in neuroendocrine regulation leading to chronic inflammation, lowered testosterone levels, increased oxidative stress, and growth hormone imbalance may underlie the association between short sleep duration and frailty [34, 35]. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, several similar mechanisms underlie the association between long sleep duration and frailty. First, long sleep duration is associated with poor health and reduced physical function [36, 37], which increases frailty risk [38, 39]. Second, people with long sleep durations have high levels of pro-inflammatory factors, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 [40], which are positively associated with frailty [41]. In addition, elevated melatonin and cortisol levels, lower body temperature, and immune system imbalances have also been suggested to lead to frailty [42].

Previous studies have reported relationships between sleep duration and frailty components. Our study showed that the prevalence of weakness, slowness, fatigue, and physical inactivity (excluding unintended weight loss) was higher in individuals with short or long sleep duration than in to those with middle sleep duration. The results were similar for women, but for men, only weakness and slowness were statistically significant. Previous studies among older adults aged 65 years and above in Hong Kong and the United States reported that reduced grip strength was associated with shorter sleep duration [43] and longer sleep duration [44, 45], which is consistent with our findings. Nakakubo et al. [18] demonstrated that both short and long sleep durations were associated with slowness in both men and women, whereas Goldman et al. [46] reported that only older women with short and long sleep durations had slower gait speeds. In our study, older adults with short sleep durations had a higher rate of exhaustion, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [18, 46]. Several studies [18, 47] have also found that older adults who sleep for long durations have a higher rate of low physical activity, in line with our findings. This may be because long sleep duration is associated with poor sleep quality [48], which in turn is associated with low physical activity. The results of the present study showed that unintended weight loss was not associated with sleep duration, which is inconsistent with previous studies [45, 49]. Furthermore, previous studies [45, 49] reported that short sleep duration (< 5 h/<6 h) was associated with obesity; therefore, further research is needed to clarify this aspect. The relationship between frailty components and sleep duration differs among studies, probably due to between-study differences in participant age and ethnicity, frailty component definitions, or frailty assessment methods.

In the present study, sex-related differences were observed in the association between sleep duration and frailty. The effect of short and long sleep durations on frailty was only significant for women, and not for men; however, the underlying mechanisms are unclear. Several recent studies have addressed the possible contributors, including menopausal hormonal changes and inflammatory markers [40, 50,51,52]. In a prospective study conducted by Gale et al. [53], elevated inflammatory markers (CRP and fibrinogen) were predictive of incident frailty among women, but not among men. Women have higher levels of inflammatory markers [51], which could lead to catabolic processes and sarcopenia [54], thus increasing the frailty risk [54]. Therefore, there is a need to identify the effect of sex on frailty and clarify the underlying mechanisms. In addition, sex differences must be considered when developing future frailty prevention interventions.

This study has several limitations. First, we could not establish a causal relationship between sleep duration and frailty due to the cross-sectional study design. Because the association between sleep duration and frailty could be bi-directional in nature, future research should be conducted to further evaluate this causal relationship. Second, sleep duration was measured using a self-reported questionnaire. Although this is commonly applied in population-based studies, it may lead to recall bias and inaccurate results. Thus, future studies using more objective measures, such as actigraphy, are required. Third, the data used for analysis were existing secondary data from KNHANES, which were not specifically collected for sleep and frailty research. Thus, this study did not consider hypnotic drug use, pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., CRP, interleukin-6), cortisol levels, sex hormones, and various diseases (e.g., obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, obstructive apnea, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cognitive impairment), all of which can affect sleep duration and frailty. To clarify the relationship between sleep duration and frailty in older adults, we propose conducting future research that includes all of these confounding factors. Despite these limitations, our study results are meaningful because they reveal a significant association between sleep duration and frailty in a large number of participants representative of the Korean community-dwelling older adults. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first Korean study to identify sex-based differences in the relationship between sleep duration and frailty.

Conclusion

This nationwide survey of representative community-dwelling Korean older adults demonstrated that both short and long sleep durations were independently associated with frailty in women, but not in men. Therefore, the management of sleep problems among women should be prioritized and effective frailty prevention interventions should be developed accordingly. Large-scale longitudinal studies that overcome the limitations of this study would provide a more detailed understanding of the causal relationship between sleep duration and frailty.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- KCDC:

-

Korea Center for Disease Control

- KNHANES:

-

Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

References

Shim EY, Ma SH, Hong SH, Lee YS, Paik WY, Seo DS, et al. Correlation between frailty level and adverse health-related outcomes of community-dwelling elderly, one year retrospective study. Korean J Fam Med. 2011;32:249–56. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.2011.32.4.249.

Chang SF, Lin HC, Cheng CL. The relationship of frailty and hospitalization among older people: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50:383–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12397.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

Kang MG, Kim OS, Hoogendijk EO, Jung HW. Trends in frailty prevalence among older adults in Korea: a nationwide study from 2008 to 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(29):e157. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e157.

Zhang Q, Guo H, Gu H, Zhao X. Gender-associated factors for frailty and their impact on hospitalization and mortality among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional population-based study. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4326. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4326.

Kojima G, Iliffe S, Taniguchi Y, Shimada H, Rakugi H, Walters K. Prevalence of frailty in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol. 2017;27(8):347–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.je.2016.09.008.

Zhou Q, Li Y, Gao Q, Yuan H, Sun L, Xi H, Wu W. Prevalence of frailty among Chinese community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605964. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605964.

Statistics Korea. Future Population Special Estimation; 2020–2070 (Press Release), 2021.12.9. pp. 12–23.

Gobbens RJ, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58:76–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2009.09.005.

Puts MTE, Lips P, Deeg DJH. Static and dynamic measures of frailty predicted decline in performance-based and self-reported physical functioning. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1188–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.008.

Jaussent I, Bouyer J, Ancelin ML, Akbaraly T, Pérès K, Ritchie K, et al. Insomnia and daytime sleepiness are risk factors for depressive symptoms in the elderly. Sleep. 2011;34:1103–10. https://doi.org/10.5665/SLEEP.1170.

Lu L, Wang SB, Rao W, Zhang Q, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The prevalence of sleep disturbances and sleep quality in older Chinese adults: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17:683–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1469492.

Kim WJ, Joo WT, Baek J, Sohn SY, Namkoong K, Youm Y, et al. Factors associated with insomnia among the elderly in a rural community in a Korean rural community. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(4):400–6. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2017.14.4.400.

Gu HJ. The relationship between the level of frailty and sleep duration of the older adults in Korea. J Converg Inf Technol. 2022;12(2):94–106. https://doi.org/10.22156/CS4SMB.2022.12.02.094.

Li J, Cao D, Huang Y, Chen Z, Wang R, Dong Q, et al. Sleep duration and health outcomes: an umbrella review. Sleep Breath. 2022;26:1479–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-021-02458-1.

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Ancoli-Israel S, Redline S, Cawthon PM, Paudel ML, et al. Sleep disturbances and risk of frailty and mortality in older men. Sleep Med. 2012;13:1217–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2012.04.010.

Lee JSW, Auyeung TW, Leung J, Chan D, Kwok T, Woo J, et al. Long sleep duration is associated with higher mortality in older people independent of frailty: a 5-year cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:649–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.006.

Nakakubo S, Makizako H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Lee S, et al. Long and short sleep duration and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:1066–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1116-3.

Baniak LM, Yang K, Choi J, Chasens ER. Long sleep duration is associated with increased frailty risk in older community-dwelling adults. J Aging Health. 2020;32:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318803470.

Kang I, Kim S, Kim BS, Yoo J, Kim M, Won CW. Sleep latency in men and sleep duration in women can be frailty markers in community-dwelling older adults: the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS). J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1109-2.

Moreno-Tamayo K, Manrique-Espinoza B, Morales-Carmona E, Salinas-Rodríguez A. Sleep duration and incident frailty: the rural Frailty Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:368. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02272-0.

Zhao Y, Lu Y, Zhao W, Wang Y, Ge M, Zhou L, et al. Long sleep duration is associated with cognitive frailty among older community-dwelling adults: results from West China Health and Aging Trend Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:608. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02455-9.

Akın S, Özer FF, Zararsız GE, Şafak ED, Mucuk S, Arguvanlı S, et al. The impact of sleep duration on frailty in community-dwelling Turkish older adults. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2020;18:243–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00264-y.

Moreno-Tamayo K, Ramírez-García E, Sánchez-García S. Sleep disturbances are associated with frailty in older adults. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2018;56(Suppl 1):S38–44.

Sun XH, Ma T, Yao S, Chen ZK, Xu WD, Jiang XY, et al. Associations of sleep quality and sleep duration with frailty and pre-frailty in an elderly population Rugao longevity and ageing study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1407-5.

Yang S, Jang W, Kim Y. Association between frailty and dietary intake amongst the Korean elderly: based on the 2018 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Nutr Health. 2021;54:631–43. https://doi.org/10.4163/jnh.2021.54.6.631.

Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Bahyah KS, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025.

Kim SH, Ahn J, Ock M, Shin S, Park J, Luo N, et al. The EQ-5D-5L valuation study in Korea. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1845–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1205-2.

Grossi G, Jeding K, Söderström M, Osika W, Levander M, Perski A. Self-reported sleep lengths ≥ 9 hours among Swedish patients with stress-related exhaustion: associations with depression, quality of sleep and levels of fatigue. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69:292–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2014.973442.

Savela SL, Koistinen P, Stenholm S, Tilvis RS, Strandberg AY, Pitkälä KH, et al. Leisure-time physical activity in midlife is related to old age frailty. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1433–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt029.

Seo MH, Lee WY, Kim SS, Kang JH, Kang JH, Kim KK, et al. 2018 Korean society for the study of obesity guideline for the management of obesity in Korea. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2019;28:40–5. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes.2019.28.1.40.

Moreno-Tamayo K, Manrique-Espinoza B, Ortiz-Barrios LB, Cárdenas-Bahena Á, Ramírez-García E, Sánchez-García S. Insomnia, low sleep quality, and sleeping little are associated with frailty in Mexican women. Maturitas. 2020;136:7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.03.005.

Gordon EH, Peel NM, Samanta M, Theou O, Howlett SE, Hubbard RE. Sex differences in frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2017;89:30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.021.

Hall MH, Smagula SF, Boudreau RM, Ayonayon HN, Goldman SE, Harris TB, et al. Association between sleep duration and mortality is mediated by markers of inflammation and health in older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Sleep. 2015;38:189–95. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4394.

Piovezan RD, Abucham J, Dos Santos RVT, Mello MT, Tufik S, Poyares D. The impact of sleep on age-related Sarcopenia: possible connections and clinical implications. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;23:210–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.07.003.

Jike M, Itani O, Watanabe N, Buysse DJ, Kaneita Y. Long sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.011.

Zhai L, Zhang H, Zhang D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:664–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22386.

Vetrano DL, Palmer K, Marengoni A, Marzetti E, Lattanzio F, Roller-Wirnsberger R, et al. Frailty and multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74:659–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly110.

Yuan L, Chang M, Wang J. Abdominal obesity, body mass index and the risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50:1118–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab039.

Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:40–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.014.

Soysal P, Stubbs B, Lucato P, Luchini C, Solmi M, Peluso R, et al. Inflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;31:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.006.

Aeschbach D, Sher L, Postolache TT, Matthews JR, Jackson MA, Wehr TA. A longer biological night in long sleepers than in short sleepers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:26–30. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-020827.

Spira AP, Covinsky K, Rebok GW, Punjabi NM, Stone KL, Hillier TA, et al. Poor sleep quality and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1092–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03968.x.

Auyeung TW, Kwok T, Leung J, Lee JS, Ohlsson C, Vandenput L, et al. Sleep duration and disturbances were associated with testosterone level, muscle mass, and muscle strength: a cross-sectional study in 1274 older men. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:e6301–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.04.006.

Dam TTL, Ewing S, Ancoli-Israel S, Ensrud K, Redline S, Stone K, et al. Association between sleep and physical function in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men sleep study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1665–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01846.x.

Goldman SE, Ancoli-Israel S, Boudreau R, Cauley JA, Hall M, Stone KL, et al. Sleep problems and associated daytime fatigue in community-dwelling older individuals. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1069–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/63.10.1069.

Stenholm S, Kronholm E, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Self-reported sleep duration and time in bed as predictors of physical function decline: results from the InCHIANTI study. Sleep. 2011;34:1583–93. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1402.

Patel SR, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men-MrOS Research Group. Sleep characteristics of self-reported long sleepers. Sleep. 2012;35:641–8. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1822.

Patel SR, Blackwell T, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, et al. The association between sleep duration and obesity in older adults. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1825–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.198.

Xu M, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Guay B, Zhang J, Morin CM. Comparison of subjective and objective sleep quality in menopausal and non-menopausal women with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2011;12:65–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.003.

Yang Y, Kozloski M. Sex differences in age trajectories of physiological dysregulation: inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and allostatic load. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:493–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glr003.

Gordon EH, Hubbard RE. Differences in frailty in older men and women. Med J Aust. 2020;212:183–8. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50466.

Gale CR, Baylis D, Cooper C, Sayer AA. Inflammatory markers and incident frailty in men and women: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:2493–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-013-9528-9.

Ershler WB. A gripping reality: oxidative stress, inflammation, and the pathway to frailty. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103:3–5. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00375.2007.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, B.H., M.H.; methodology, W.Y.S., S.K.; formal analysis, B.H., M.H.; investigation, W.Y.S., S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.H., M.H.; writing—review and editing, W.Y.S., S.K.; supervision, B.H., M.H.; funding acquisition, W.Y.S., S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Center for Disease Control (Institutional Review Board number: 2018-01-03-P-A). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ha, B., Han, M., So, WY. et al. Sex differences in the association between sleep duration and frailty in older adults: evidence from the KNHANES study. BMC Geriatr 24, 434 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05004-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05004-2