Abstract

Background

The association between socioeconomic status and depression is weaker in older adults than in younger populations. Loneliness may play a significant role in this relationship, explaining (at least partially) the attenuation of the social gradient in depression. The current study examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and depression and whether the association was affected by loneliness.

Methods

A cross-sectional design involving dwelling and nursing homes residents was used. A total of 887 Spanish residents aged over 64 years took part in the study. Measures of Depression (GDS-5 Scale), Loneliness (De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale), Socioeconomic Status (Education and Economic Hardship), and sociodemographic parameters were used. The study employed bivariate association tests (chi-square and Pearson’s r) and logistic regression analyses.

Results

The percentage of participants at risk of suffering depression was significantly higher among those who had not completed primary education (45.5%) and significantly lower among those with university qualifications (16.4%) (X2 = 40.25;p <.001), and respondents who could not make ends meet in financial terms faced a higher risk of depression (X2 = 23.62;p <.001). In terms of the respondents who experienced loneliness, 57.5% were at risk of depression, compared to 19% of those who did not report loneliness (X2 = 120.04;p <.001). The logistic regression analyses showed that having university qualifications meant a 47% reduction in the risk of depression. This risk was 86% higher among respondents experiencing financial difficulties. However, when scores for the loneliness measure were incorporated, the coefficients relating to education and economic hardships ceased to be significant or were significantly reduced.

Conclusion

Loneliness can contribute to explaining the role played by socioeconomic inequalities in depression among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a key issue during ageing. In Europe, depression is more prevalent among people aged over 64 years than among other age groups [1]. Depression decreases quality of life for older adults [2] and increases the risk of deterioration of health and functionality [3, 4]. The existing literature has confirmed the significance of socioeconomic status (SES) for mental health among older adults. Specifically, the empirical evidence indicates the presence of a socioeconomic gradient in the case of depression [5]. There are two main indicators for SES in the literature on health: education and income [6]. Several studies have shown that education is linked to a lower prevalence of depression [7] and can be a significant protective factor [8]. However, other studies have not identified a significant association between education and depressive symptoms [9] and some studies have even reported higher scores for depression among those with higher levels of education [10]. In short, as noted by Li and Zhao [11], the empirical evidence on the relationship between education and depression in later life is inconclusive.

The literature on ageing also reports an inconclusive relationship between income and depression, with some studies finding a significant association and others not [12,13,14]. In fact, as with education, the association between income and depression is heavily influenced by contextual variables (State, national) [5] related to policies for the protection of older adults, and particularly pension and health systems. As stated in these studies [15], it can be difficult to use income as a measure for SES in the case of older adults given that in a majority of cases this income derives from standards established by retirement systems following the cessation of employment. In this regard, economic hardship would be a more accurate approach to examine the role that income plays in psychological wellbeing among older adults, and particularly as regards depressive symptoms. The concept of economic hardship describes a situation where someone has insufficient income to cover their daily socioeconomic needs. This process acts as a stressor for individuals (financial strain) and threatens their ability to meet basic needs. Its relationship with depression has been reported in numerous studies [16,17,18,19]. More specifically, the existing research underlines the role played by recent economic hardship, which has a greater impact on depressive symptoms than difficulties experienced in the more distant past [20]. Finally, it is worth noting the work of Sun et al. [21], who found that financial stress continues to affect mental health even when controlled by household income, which suggests that its potential effect may be only partly related to income.

In summary, an analysis of the published empirical evidence shows that the SES gradient for depression among older adults is characterised by specific elements compared to other age groups. In fact, several articles suggest that inequalities of this kind are reduced in the case of older adults. In other words, there are processes that are characteristic of ageing and reduce the social gradient in health, meaning that SES might not be such a significant determinant compared to its impact among the younger or middle-aged population [22]. This hypothesis, which can be defined as the age-as-leveller hypothesis, suggests that socioeconomic differences in health increase during adulthood and accumulate to affect health during middle age. However, the following factors come into play at older ages: (a) biological processes leading to increased fragility; and (b) social, economic and health policies specifically aimed at older people. Both processes contribute to reducing the effects of low SES on health, causing a weakening of the education and income gradients with older age [23].

The impact of psychosocial processes closely linked to ageing also has to be taken into account in the case of mental health, and particularly depression. In this paper, we propose that loneliness is one of these factors. In this regard, the aim of this research was to analyse the relationship between socioeconomic status and depression and whether the association was affected by loneliness. The starting point was to consider loneliness as a key process to understand the role played by SES in depression among older adults. With good reason, the study of loneliness has recently become one of the key lines of research regarding the wellbeing of older adults [24]. The existing evidence had already demonstrated the importance of relationships and social support for depression among older people [25]. This evidence showed that functional aspects of social support from various sources act as buffers against negative life experiences, thereby reducing the potential of such experiences to cause depression [26]. The literature examining loneliness has focused on this line of study. The ageing process is characterised by the narrowing of support networks and a potential increase in situations of loneliness [27]. Loneliness is an unpleasant experience that occurs when social relationships are insufficient in quantity and quality [28]. Along these lines, de Jong-Gierveld [29, p.73–74] defined loneliness as “a situation in which the number of existing relationships is smaller than is considered desirable, as well as situations where the intimacy one wishes for has not been realized”. Various authors have described the multidimensional nature of this concept [30]. Emotional and social loneliness are frequently distinguished in this regard. The former arises from a lack of the emotional support provided by close relationships, while the latter occurs in the absence of an adequate social network. The available empirical evidence has shown that loneliness is a risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms among older people [31, 32]. As part of their systematic review, Lambert Van As et al. [33] concluded that the published literature shows the existence of both a longitudinal association between loneliness and depressive symptoms and an unfavourable course of depression associated with loneliness.

As previously stated, the aim of this research was to analyse the role that loneliness plays in the relationship between SES and depression. The findings of recent studies suggest that loneliness and SES are inter-related processes, with objective financial measures of financial strain (such as income, financial downturn and income disparities) associated with higher levels of loneliness [34,35,36]. Specifically, subjective measures of financial strain are associated with higher levels of loneliness, and this association could be even more intense than the link with objective measures of economic hardship [37]. There is contradictory empirical evidence in the case of education. Some studies suggest that loneliness is more intense and/or frequent among people with lower levels of education [38,39,40], but others have found no association [41, 42] and there are even studies whose findings suggest that higher qualifications are associated with greater experiences of loneliness [43].

It hence appears important to empirically analyse the relationship between SES and depression, taking into account the role that loneliness plays in that relationship. More specifically, this study was based on the following particular aims: (a) to analyse the association between SES and experiences of loneliness; (b) to analyse the association between SES and depression; (c) to identify changes to the pattern of association between SES and depression as a result of the incorporation of (emotional and social) loneliness into the analyses; and (d) to explore the existence of interaction between SES and loneliness in the case of depression.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

A total of 887 Spanish residents took part in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) aged at least 65 years; (b) living with partner (no other people living at home) or living alone, or residing in a nursing home for more than six months; (c) no severe cognitive impairment; and (d) able to communicate. For community-dwelling participants, the procedure included the application of the Mini-Mental State Examination test only in cases where signs of severe cognitive impairment were detected (mild cognitive impairment was not an exclusion criterion) at the time of informing participants about the study objectives and requesting their consent. On the other hand, the researchers collaborated with the professionals of the nursing homes to identify participants who met the inclusion criteria for the study. The participants’ mean age was M = 78.5, SD = 8.7, and 62% of participants were women.

The data were collected using a survey administered by trained personnel. Following the initial contact with potential participants and once their informed consent had been obtained, the surveys were applied under the conditions chosen by those who agreed to take part. For nursing home residents, the surveys were applied in an area of their nursing home that ensured the interview would be confidential. All study procedures were approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Universidad Complutense (Madrid) (report reference CE_20220217-14_SOC).

Measures

Outcome variable

Depression. The five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-5) was used. The short version of the Geriatric Depression Scale maintains the effectiveness of the original scale while improving ease of administration [44]. This instrument is used to record the presence of five depressive symptoms, producing a score ranging from 0 to 5. The validation of the five-item version in Spain [45] showed adequate sensitivity levels that are comparable to those of the two longer versions. The cut-off point of ≥2, recommended by Hoyl et al. [44] was used for the identification of potential cases. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.701.

Exposure variables

Loneliness. The six-item version of the De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale [46] (DJGLS) was used. The DJGLS scale was validated in Spain by Ayala et al. [47] for a sample of older adults. It is a short and commonly used instrument in loneliness research that produces an overall score and two sub-scores for social and emotional loneliness. This multidimensional approach makes this instrument the most appropriate one to achieve the aims of this research. Items are scored on a scale from 0 to 2, although they are subsequently recodified as dichotomous (0 or 1). The scale include items that required reverse scoring, such as ‘There are many people I can trust completely.’ The recoding process ensured consistency in the direction of responses. Higher scores on the total scale indicate stronger feelings of loneliness (range from 0 to 6). The loneliness scale was used in two ways for the analyses on which this article is based. First, the total scores for both subscales (emotional and social loneliness) were used as predictive variables for the outcome variable values. Second, participants with an overall DJGLS score of 3 or higher were classified as being in situations involving a risk of loneliness. Typically, three cut-off points are used for this scale (0–1: not lonely; 2–4: moderately lonely; 5–6: strongly lonely). However, de Jong-Gierveld and Van Tilburg [48, p.12] point out that “there is the problem that the scale for emotional loneliness is more closely related to the direct question of loneliness than the scale for social loneliness. It also applies that an equal cut-off point for both subscales does not result in a similar score on the shortened scale”. In the present study, the cut-off point to identify a situation of risk of loneliness (versus no risk) was established, following the strategy of Rodríguez-Blázquez et al. [49]. The analyses were carried out separately to avoid collinearity risks. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.751.

Socioeconomic status (SES). Two indicators were selected to measure socioeconomic status. First of all, level of education was used given its recognised value as an indicator of SES in the literature on social determinants of health [6]. Education was classified into four large categories in this study: incomplete primary education (including unqualified people); completed primary education; secondary education; and university education. Economic hardship was used as the second indicator: the presence of difficulties making ends meet in financial terms. This indicator is frequently used to indirectly measure limitations arising from income levels. The following specific item was used: “Regardless of your household income and taking into account your total monthly income, would you say you can make ends meet?”. Four response categories were offered: (1) easily; (2) reasonably easily; (3) with some difficulty; and (4) with great difficulty. Categories 1 and 2 were combined, as were categories 3 and 4, to produce a dichotomous variable (1 = difficulties making ends meet).

Control variables

The variables of sex (1 = female), age, children (1 = no children) and limitations on activities of daily living due to health problems were incorporated. The latter variable was evaluated using the Global Activity Limitation Indicator (GALI) [50]. The GALI consists of a single item (“For at least the last six months, have you been limited because of a health problem in activities people usually do?”), with three response categories (yes, strongly limited; yes, limited; no, not limited). The GALI is a useful and valid instrument to assess global activity limitation in both health and non-health surveys.

Living arrangement. This was used as a control variable in models that included loneliness among the predictors of the outcome variable. This decision was based on the available empirical evidence regarding the notable impact of the three situations taken into account in this study (living with partner only; living alone; living in a nursing home) on levels of loneliness experienced by older adults when compared with other living arrangements [51, 52].

Analysis

First, the descriptive statistics of the study variables and bivariate association statistics were obtained. Second, a logistic regression analysis was performed to test the fit of five models. The base model only incorporated the control variables. The SES indicators were then included in the equation (model 2: “Socioeconomic Status”). The third model (“Loneliness”) included the dimensions of loneliness considered in the study. Models 4 and 5 successively incorporated interactions between the variables related to SES and loneliness. Third, the logistic regression equations for models 3 to 5 were calculated by replacing the scores for the two dimensions of loneliness (emotional and social) with a variable estimating the existence of a risk of loneliness based on a cut-off point (as described in the previous section).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of the main study variables. The high prevalence of depression and loneliness is due to the sample composition. In fact, the present study included participants living alone, with their partner, or in a nursing home, precisely because such living arrangements are especially relevant to the study of loneliness. In this sense, it was necessary to ensure the presence of a sufficient number in the sample of each situation, especially in the case of people living in a residence (20.7% of the participants). Table 1 disaggregates the information according to living arrangements. As expected, the percentage of people with limitations in ADL due to health problems is higher among those who live in a nursing home. The percentage of women and childless people is also higher. On the other hand, economic hardships are less frequent in this group. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the quantitative study variables. As may be observed, all coefficients are significant except for that measuring the association between age and social loneliness.

The results for the bivariate analyses referring to qualitative variables (see Table 3) showed that the risk of being above the GDS-5 cut-off point (for depression) was higher for women (χ2 = 10.45;p <.001) and lower for those who did not suffer limited mobility owing to illness (χ2 = 106.34;p <.001) than for those who faced mild or serious limitations. In addition, the percentage of participants at risk of depression was significantly higher among those who had not completed primary education (45.5%) and significantly lower among those who had obtained university qualifications (16.4%) (χ2 = 40.25;p <.001). Meanwhile, participants who had difficulty making ends meet faced a higher risk of depression (X2 = 23.62;p <.001). Residential status was also significantly associated with the risk of depression (χ2 = 77.34;p <.001). Specifically, 54.3% of people in nursing homes and 29.5% of those living alone were above the established cut-off point, compared to 18.1% of those living with a partner. Notably, 57.5% of those experiencing loneliness were at risk of depression, as opposed to 19% of those who were not experiencing loneliness (χ2 = 120.04;p <.001).

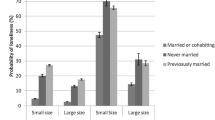

Bivariate analyses were conducted for loneliness and the other variables (Table 3), due to the importance of loneliness for this study. The findings showed no differences between men and women, with experiences of loneliness more common among participants who did not have children (χ2 = 17.77;p <.001) and those who faced limitations affecting their daily activities (χ2 = 42.24;p <.001). The percentage of people experiencing loneliness was significantly lower among participants with university qualifications (15.2%) and significantly higher (38.4%) among unqualified participants (χ2 = 10.45;p <.001). Strikingly, 39.9% of people with difficulties making ends meet experienced loneliness, compared to 19.6% in the case of people who did not face economic hardship (χ2 = 34.84;p <.001). Finally, 44.5% of participants living in nursing homes and 29.1% of those living alone were above the cut-off point for loneliness. This percentage fell to 15.4% among those living with a partner (χ2 = 51.95;p <.001).

Table 4 summarises the results obtained from the logistic regression analysis incorporating the two dimensions of loneliness (emotional and social) as quantitative variables. As may be observed, in model 2 the variables related to socioeconomic status had a statistically significant association with the outcome variable, such that having university qualifications implied a 47% reduction in the likelihood of depression. In contrast, the likelihood of depression was 86% higher among those experiencing economic hardship. Table 4 demonstrates the importance of living arrangements, with the potential for depression being 103% higher among those living in nursing homes. However, model 3 represents a notable shift in the range of variables significantly associated with the depression measure (GDS-5). This model incorporated the two dimensions of loneliness considered in the study: emotional and social. Of these two, only the former showed a positive and statistically significant association with the outcome variable, meaning that the likelihood of identifying a case of depression increased in the presence of emotional loneliness. The inclusion of social loneliness in the model did not result in a significant association at p <.05 level; however, it should be noted that there was such an association at p <.10 level. Notably, incorporating the two dimensions of loneliness into model 3 meant that the coefficients for education and economic hardship were not significant, although living in a nursing home continued to play the same role. Neither of the models that included interactions between SES and loneliness (models 4 and 5) implied an improvement compared to model 3.

Table 5 shows the results for calculating the models’ goodness-of-fit by replacing the quantitative variables of emotional and social loneliness with a variable that covers the potential identification of a case of loneliness. As described in the methodology section, a cut-off point of 3 was established. Table 5 hence reproduces the logic of the models defined for this study, making it possible to calculate the difference in the likelihood of identifying a case of depression among those people who are suffering potential situations of loneliness (or not). As might be expected, the results were consistent with those set out in Table 4. However, it should be noted that in model 3 the significant association between loneliness and depression entailed a difference in likelihood of over 300% compared to people who were not potentially in a position of loneliness. In addition, that model maintains a significant coefficient for the economic hardship measure, which increased the likelihood of depression by 51%. Finally, only the interaction between primary education and the potential presence of loneliness produced a significant coefficient (models 4 and 5), although it is necessary to take into account that its incorporation does not significantly improve explained variance.

To confirm the robustness of the findings, the results obtained for model 3 were further validated by bootstrapping analysis (random sampling, n = 1.000). The results are shown in Table 6. For all the variables included in the model, the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals obtained in the analysis replicate the results obtained in the original analysis. Taken as a whole, these results suggest stability and consistency in the findings obtained in this study.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study add empirical evidence for the association between SES and depression among older people. Both the bivariate analyses and models 1 and 2 of the logistic regression analysis suggest that low levels of education and the presence of economic hardship are associated with high scores for the depression measure [53, 54]. Tables 3 and 4 show that the incorporation of SES into model 2 of our logistic regression analyses resulted in statistically significant association coefficients, meaning that people with university qualifications showed a lower likelihood of being identified as potential cases of depression, while those experiencing economic hardships were in the opposite situation. There was an increase of 32% in explained variance for the outcome variable (depression) in model 2 compared to model 1 (the latter model only including the control variables, sex, age, children and limitations affecting mobility). This implies a moderate but significant predictive capacity of SES in terms of scores for depression.

However, the main contribution of this study was the analysis of the role played by loneliness in the association between SES and depression among older adults. In this regard, model 3 added the following to the logistic regression analysis: (a) scores for emotional and social loneliness, to predict the scores for the depression variable (Table 3); and (b) identification of a potential case of loneliness and its relationship to the existence of a potential case of depression (Table 4). These results specifically refer to the main research aim, which was to analyse the role played by loneliness in the relationship between SES and depression. First of all, the results shown in Table 3 indicated a significant association only between emotional loneliness and the existence of a potential case of depression, but not in the case of social loneliness. Moreover, and this is particularly significant, the incorporation of this association meant that the regression coefficients for level of education and economic hardship ceased to be significant. Similar results were obtained when introducing the loneliness variable into model 3 as a dichotomous variable (presence/absence) (Table 4). The only variation consisted of economic hardship maintaining a significant association with depression, although it is important to note that the intensity of that association was significantly reduced.

These results show that the relationship between socioeconomic status and depression among the older people who took part in the study was significantly affected by their experience of loneliness. In other words, the positive association between socioeconomic disadvantages and depression could arise indirectly as a result of its link to loneliness. Our results suggest that this is a plausible explanation, insofar as loneliness was significantly more prevalent in our sample among unqualified people than those with university qualifications. Moreover, loneliness occurred more frequently among participants who were experiencing economic hardship. These results coincide with those obtained in previous studies [35, 55, 56]. In this regard, socioeconomic difficulties can restrict relationships for older adults in terms of their social lives, limiting opportunities to take part in sociocultural activities and curtailing access to community resources that are valuable in combating loneliness [39], such that low SES during the ageing process can result in the truncation of social links [34]. It is even possible that low SES (meaning less education and more economic deprivation) may be related to living in contexts– whether neighbourhoods or nursing homes– offering social, economic, cultural and environmental resources that do not support people’s needs for socialisation and intimacy as they age. In other words, socioeconomic inequalities during ageing are reflected in the resources that comprise the place of residence, meaning that those in privileged social positions have greater enjoyment of age-friendly communities that “strive to find the best fit between the various needs and resources of older residents and those of the community” [57].These may include psychosocial resources, insofar as low income and lower levels of education can have an impact on self-esteem, self-efficacy and sense of mastery [17, 37]. These processes are closely related to the experience of emotional loneliness, on one hand, and depression, on the other [58].

In any case, rather than being confined to influencing the potential impact of SES, loneliness played a specific role in the results of this study (hence the 67% increase in explained variance when introducing this variable into our models compared to the model that only included SES). It is worth taking into account that recent studies have shown that the impact of socioeconomic inequalities on depression among older adults varies notably from country to country. Findings reported by Richardson et al. [59] using data corresponding to 18 countries in North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East suggest considerable variability related to country-specific characteristics, such that they are more significant than any regional characteristics. In the European context, Sánchez-Moreno and Gallardo-Peralta [60] noted that one of the contextual factors with the greatest impact on the relationship between SES and depression is the level of perceived social support. In this regard, there were country-by-country variations in terms of the extent to which perceived social support was a protective factor against depression.

Along these lines, the link between loneliness and depression may be particularly significant in societies where accompaniment and support during difficult life situations falls essentially to support networks in general, and families in particular. This is true of Spain, where family support is a key cultural factor as a mechanism for social protection and psychosocial accompaniment [61]. Difficulties in generating intimate and reciprocal two-way relationships may increase the impact of loneliness on the deterioration of wellbeing during the ageing process [62]. At the same time, this relationship could be intensified in less resourceful contexts, in which SES (and particularly education and income) would be more significant in combating the negative effects of loneliness on depression [11]. In these contexts, people with more education and income would be less susceptible to the deleterious effects of loneliness.

The main limitation of this study concerns its cross-sectional design, which hinders an analysis of the impact of the variations of loneliness on depression, controlled by the dimensions of SES taken into account (education and economic hardship). In this context, moreover, the fact that loneliness levels can fluctuate over time needs to be taken into account. Awad et al. [63] suggest that this variation can occur on a weekly basis. This means that the specific time when the measurement is taken might not offer a general reflection of the experience of loneliness among interviewees. Finally, the loneliness scale used in this study is generally a reliable and valid measure across different countries. However, some still argue that gender and/or cultural differences may influence the response to the items of the scale [64].

Conclusion

Alongside these limitations, this study suggests that loneliness– particularly emotional loneliness– can contribute to explaining the role played by socioeconomic inequalities in depression among older adults. Taking it into account when designing intervention plans could therefore contribute to reducing the social gradient in mental health for this group. In this regard, future research could further the understanding of the role that loneliness plays in the debate regarding social inequalities in health during the ageing process, and specifically the age-as-leveller hypothesis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available at the moment due to temporary restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arias-de la Torre J, Vilagut G, Ronaldson A, et al. Prevalence and variability of current depressive disorder in 27 European countries: a population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(10):e729–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00047-5.

Wels J. Assessing the impact of partial early retirement on self-perceived health, depression level and quality of life in Belgium: a longitudinal perspective using the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Ageing Soc. 2020;40(3):512–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18001149.

Curran E, Rosato M, Ferry F, Leavey G. Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression in older adults: gender differences in psychosocial indicators. J Affect Disord. 2020;267:114–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.018.

Rodda J, Walker Z, Carter J. Depression in older adults. BMJ. 2011;343:d5219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d521.

Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf182.

Schnittker J. Education and the changing shape of the income gradient in health. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):286–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650404500304.

Mohebbi M, Agustini B, Woods RL, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and its associated factors among healthy community-dwelling older adults living in Australia and the United States. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(8):1208–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5119.

Murchland AR, Eng CW, Casey JA, Torres JM, Mayeda ER. Inequalities in elevated depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults by rural childhood residence: the important role of education. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(11):1633–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5176.

Rutland-Lawes J, Wallinheimo AS, Evans SL. Risk factors for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in middle-aged and older adults. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(5):e161. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.997.

Nyberg A, Peristera P, Magnusson Hanson LL, Westerlund H. Socio-economic predictors of depressive symptoms around old age retirement in Swedish women and men. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(5):558–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1430741.

Li Y, Zhao D. Education, neighbourhood context and depression of elderly Chinese. Urban Stud. 2021;58(16):3354–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098021989948.

Brinda EM, Rajkumar AP, Attermann J, Gerdtham UG, Enemark U, Jacob KS. Health, social, and economic variables associated with depression among older people in low and middle income countries: World Health Organization Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(12):1196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.07.016.

Freeman A, Tyrovolas S, Koyanagi A, et al. The role of socio-economic status in depression: results from the COURAGE (aging survey in Europe). BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1098. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3638-0. Published 2016 Oct 19.

Hoebel J, Maske UE, Zeeb H, Lampert T. Social inequalities and depressive symptoms in adults: the role of objective and subjective socioeconomic status. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169764. Published 2017 Jan 20.

Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH. Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. Am J Sociol. 2007;112(6):1886–924. https://doi.org/10.1086/512712.

Cheruvu VK, Chiyaka ET. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care: findings from a nationally representative sample. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1203-2. Published 2019 Jul 18.

Pudrovska T, Schieman S, Pearlin LI, Nguyen K. The sense of mastery as a mediator and moderator in the association between economic hardship and health in late life. J Aging Health. 2005;17(5):634–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305279874.

Mendes de Leon CF, Rapp SS, Kasl SV. Financial strain and symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and women: a longitudinal study. J Aging Health. 1994;6(4):448–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/089826439400600402.

Marshall GL, Kahana E, Gallo WT, Stansbury KL, Thielke S. The price of mental well-being in later life: the role of financial hardship and debt. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(7):1338–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1758902.

Kahn JR, Pearlin LI. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(1):17–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650604700102.

Sun F, Hilgeman MM, Durkin DW, Allen RS, Burgio LD. Perceived income inadequacy as a predictor of psychological distress in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(1):177–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014760.

Robert SA, Cherepanov D, Palta M, Dunham NC, Feeny D, Fryback DG. Socioeconomic status and age variations in health-related quality of life: results from the national health measurement study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(3):378–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp012.

Seeman T, Merkin SS, Crimmins E, Koretz B, Charette S, Karlamangla A. Education, income and ethnic differences in cumulative biological risk profiles in a national sample of US adults: NHANES III (1988–1994). Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):72–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.027.

Gallardo-Peralta LP, Sánchez-Moreno E, Rodríguez Rodríguez V, García Martín M. Studying loneliness and social support networks among older people: a systematic review in Europe. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2023;97:e202301006.

Russell DW, Cutrona CE. Social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among the elderly: test of a process model. Psychol Aging. 1991;6(2):190–201. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.6.2.190.

Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles. 1987;17:737–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00287685.

Sánchez Rodriguez MM, de Jong Gierveld J, Buz J. Loneliness and the exchange of social support among older adults in Spain and the Netherlands. Ageing Soc. 2014;34(2):330–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000839.

Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. Personal relationships: 3. Relationships in Disorder. London: Academic; 1981. pp. 83–95.

de Jong Gierveld J. A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Rev Clin Gerontol. 1998;8(1):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259898008090.

Perlman D, Peplau L. Loneliness. In: H.S. Friedman HS, editor. Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Vol. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 571–581.

Domènech-Abella J, Mundó J, Haro JM, Rubio-Valera M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: longitudinal associations from the Irish longitudinal study on Ageing (TILDA). J Affect Disord. 2019;246:82–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.043.

Rokach A. The psychological journey to and from loneliness: development, causes, and effects of social and emotional isolation. Elsevier Academic; 2019.

Van As BAL, Imbimbo E, Franceschi A, Menesini E, Nocentini A. The longitudinal association between loneliness and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2022;34(7):657–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221000399.

de Jong Gierveld J, Keating N, Fast JE. Determinants of loneliness among older adults in Canada. Can J Aging. 2015;34(2):125–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980815000070.

Macdonald SJ, Nixon J, Deacon L. Loneliness in the city’: examining socio-economics, loneliness and poor health in the North East of England. Public Health. 2018;165:88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.003.

Tanskanen J, Anttila T. A prospective study of social isolation, loneliness, and Mortality in Finland. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2042–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303431.

Drost MA, Snyder AR, Betz M, Loibl C. Financial strain and loneliness in older adults. Appl Econ Lett. 2022;1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2152421.

Aung K. Loneliness among elderly in nursing homes. Int J Stud Child Women Elder Disabl. 2017;2:72–9.

Aylaz R, Aktürk Ü, Erci B, Öztürk H, Aslan H. Relationship between depression and loneliness in elderly and examination of influential factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(3):548–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.006.

Elsayed EBM, Etreby RRE-, Ibrahim AA-W. Relationship between Social Support, loneliness, and Depression among Elderly people. Int J Nurs Didactics. 2019;9(01). https://doi.org/10.15520/ijnd.v9i01.2412. Article 01.

Frenkel-Yosef M, Maytles R, Shrira A. Loneliness and its concomitants among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1257–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220003476.

González Ortega E, Pinedo González R, Vicario-Molina I, Palacios Picos A, Orgaz Baz MB. Loneliness and associated factors among older adults during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2023;86:101547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2023.101547.

Choi EY, Farina MP, Zhao E, Ailshire J. Changes in social lives and loneliness during COVID-19 among older adults: a closer look at the sociodemographic differences. Int Psychogeriatr. 2023;35(6):305–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610222001107.

Hoyl MT, Alessi CA, Harker JO, et al. Development and testing of a five-item version of the geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(7):873–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x.

Ortega Orcos R, Salinero Fort MA, Kazemzadeh Khajoui A, Vidal Aparicio S, de Dios del Valle R. Validation of 5 and 15 items Spanish version of the geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in primary health care setting. Rev Clin Esp. 2007;207(11):559–62. https://doi.org/10.1157/13111585.

de Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. A 6-Item scale for overall, emotional, and Social Loneliness: confirmatory tests on Survey Data. Res Aging. 2006;28(5):582–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506289723.

Ayala A, Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Frades-Payo B, et al. Psychometric properties of the functional Social Support Questionnaire and the loneliness scale in non-institutionalized older adults in Spain. Gac Sanit. 2012;26(4):317–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.08.009.

de Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T. Manual of the loneliness scale. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 2023. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/U6GCK.

Rodríguez-Blázquez C, Ayala-García A, Forjaz MJ, Gallardo-Peralta LP. Validation of the De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale, 6-item version, in a multiethnic population of Chilean older adults. Australas J Ageing. 2021;40:e100–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12893.

Robine JM, Jagger C, Euro, -REVES Group. Creating a coherent set of indicators to monitor health across Europe: the Euro-REVES 2 project. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13(3 Suppl):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/13.suppl_1.6.

Greenfield EA, Russell D. Identifying living arrangements that heighten risk for loneliness in later life: evidence from the U.S. National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Appl Gerontol. 2011;30(4):524–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464810364985.

Jansson AH, Savikko N, Kautiainen H, Roitto HM, Pitkälä KH. Changes in prevalence of loneliness over time in institutional settings, and associated factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104043.

Bielderman A, de Greef MH, Krijnen WP, van der Schans CP. Relationship between socioeconomic status and quality of life in older adults: a path analysis. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1697–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0898-y.

Xue Y, Lu J, Zheng X, et al. The relationship between socioeconomic status and depression among the older adults: the mediating role of health promoting lifestyle. J Affect Disord. 2021;285:22–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.085.

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a Meta-analysis. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2001;23(4):245–66. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2.

Solmi M, Veronese N, Galvano D, et al. Factors Associated with loneliness: an Umbrella Review of Observational studies. J Affect Disord. 2020;271:131–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.075.

Keating N, Eales J, Phillips JE. Age-Friendly Rural communities: conceptualizing ‘Best-Fit’. Can J Aging. 2013;32(4):319–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980813000408.

Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Control or defense? Depression and the sense of control over good and bad outcomes. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31(1):71–86.

Richardson RA, Keyes KM, Medina JT, Calvo E. Sociodemographic inequalities in depression among older adults: cross-sectional evidence from 18 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(8):673–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30151-6.

Sánchez-Moreno E, Gallardo-Peralta LP. Income inequalities, social support and depressive symptoms among older adults in Europe: a multilevel cross-sectional study. Eur J Ageing. 2021;19(3):663–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00670-2.

Dumitrache CG, Rubio L, Cordón-Pozo E. Successful aging in Spanish older adults: the role of psychosocial resources. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(2):181–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218000388.

Reynolds RM, Meng J, Dorrance Hall E. Multilayered social dynamics and depression among older adults: a 10-year cross-lagged analysis. Psychol Aging. 2020;35(7):948–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000569.

Awad R, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Palgi Y. Fluctuations in loneliness due to changes in frequency of social interactions among older adults: a weekly based diary study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2023;35(6):293–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610223000133.

Buz J, Pérez-Arechaederra D. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Spanish version of the 11-item De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Int Psychogeriatr Published Online April. 2014;15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214000507.

Funding

This work was supported by the Spanish Government, State Research Agency. State RandD + i Programme. Project reference: PID2020-115993RB-I00.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed substantially to the creation of this paper. LGP, ESM, and ABLR conceived and participated in this study’s planning and development. ESM, JRA, and LGP participated in the sample collection and data analysis. ESM and LGP wrote the initial and final draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article, revised the final draft, and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study protocol, including procedures and considerations, was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Complutense University (Madrid) (report reference CE_20220217-14_SOC). Participants were individually informed about the nature of the proposed study, its risks and benefits, and required to sign informed consent forms.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Moreno, E., Gallardo-Peralta, L., Barrón López de Roda, A. et al. Socioeconomic status, loneliness, and depression among older adults: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMC Geriatr 24, 361 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04978-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04978-3