Abstract

Background

Falling is a major concern for the health of older adults and significantly affects their quality of life. Identifying the various risk factors and the differences between older patients can be challenging. The objective of this study was to identify the risk factors for falls among polymedicated community-dwelling older Lebanese patients following a medication review.

Methods

In this analytical cross-sectional study, we examined the risk factors for falls in 850 patients aged ≥ 65 years who were taking ≥ 5 medications daily. The study involved conducting a medication review over the course of a year in primary care settings and using multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze the data.

Results

Our results showed that 106 (19.5%) of the 850 included patients had fallen at least once in the three months prior to the medication review. Loss of appetite and functional dependence were identified as the most significant predictors of falls ORa = 3.020, CI [2.074–4.397] and ORa = 2.877, CI [1.787–4.632], respectively. Other risk factors for falls included drowsiness ORa = 2.172, CI [1.499–3.145], and the use of beta-blockers ORa = 1.943, CI [1.339–2.820].

Conclusion

Our study highlights the importance of addressing multiple risk factors for falls among Lebanese older adults and emphasizes the need for customized interventions and ongoing monitoring to prevent falls and improve health outcomes. This study sheds light on a critical issue in the Lebanese older population and provides valuable insight into the complex nature of falls among poly-medicated Lebanese community-dwelling older adults.

Trial registration

2021REC-001- INSPECT -09–04.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Given the ageing of societies, falls among community-dwelling older adults are considered a major public health problem that needs to be addressed due to its clinical and socioeconomic implications [1].

The number of older adults in the Arab world is expected to double by 2050 and treble by 2100, with disability, functional dependence, and chronic noncommunicable diseases being the main causes of morbidity and mortality [2]. The published literature describes a high worldwide prevalence of falls (26.5%) among older adults [3]. Moreover, in Arab countries, the reported rates vary, with instances of 21.9% in Lebanon [4], 34% in Qatar [5], and a peak of 57.7% in Saudi Arabia [6]. Given the elevated prevalence rates, the World Falls guidelines advocate for the integration of fall screening into the routine comprehensive geriatric assessment of community-dwelling older adult [7].

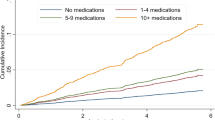

Multiple predisposing factors put community-dwelling older adults at higher risk for falls. These include sociodemographic characteristics [8,9,10], geriatric syndromes [11, 12], clinical, and medical conditions, among others [13]. Fall risk increases linearly with the number of these factors [14].

Furthermore, older patients often suffer from the existence of several comorbidities leading to the concomitant use of multiple drugs. The pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of drugs also change with age, due to decreased renal and hepatic function, altered fat distribution, and reduced metabolic rate. This results in a different response to drug therapy, rendering older adults more susceptible to adverse drug events (ADEs) if these changes are not taken into account [15,16,17,18,19]. Several studies have evaluated the association between medication use and the increased likelihood of fall [13, 20]. Three systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted by Seppala et al. highlighted the occurrence of falls associated with particular classes of medications such as cardiovascular drugs, psychotropic drugs, opioids, and proton pump inhibitors [13, 20,21,22,23].

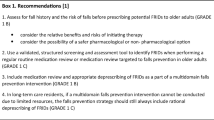

To limit ADEs associated with falls in older adults, the Swedish National Board of Health has classified certain medications as ‘fall risk-increasing drugs’ (FRIDs) [24]. Screening of all these factors including FRIDs through a medication review may be a practical way to prevent future falls.

A well-structured medication review in older patients not only leads to the optimization of medical prescriptions but also allows the pharmacist to determine what diseases the patient is suffering from, and to evaluate the adherence and management of their treatment. A thorough analysis of all these elements will make it possible to prevent further deterioration of the patient’s health and ensure his or her well-being [25,26,27,28].

In Lebanon, no previous study has evaluated the risk of falls among community-dwelling older adults and its associated factors. One study conducted at a tertiary care center in Lebanon showed that 99.2% of falls occurred at home and emphasized the importance of public awareness and the necessity of screening for fall risk factors [29].

This study aimed to look at the risk factors associated with falls in community-dwelling older Lebanese patients taking more than 5 different medications daily [30] through a medication review to address the problem of falls in older adults.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study is a secondary analytical cross-sectional study, designed to examine falls and their associated risk factors following a medication review. This study is part of the project entitled “Management of potentially inappropriate drug prescribing among Lebanese patients in primary care settings” (MGPIDP-L). The MGPIDP-L project aimed to assess potentially inappropriate drug prescribing (PIDPs) in Lebanese older patients in primary care settings (upon hospital discharge, at the patient’s home, and in community pharmacies).

Participants: Patients were systematically recruited over a 12-month period from a wide range of primary care settings, such as hospitals upon discharge, through home visits, and within community pharmacies. Contact was established with community and hospital pharmacies in Lebanon through conferences, phone calls, and mails to explain the study's rationale and methodology. Hospital pharmacists selected recently discharged patients meeting inclusion criteria, while community pharmacists displayed posters to encourage patient’s participation. Patients aged 65 years or older who were taking 5 or more medications per day, and who could provide all necessary medical information directly or with the assistance of a caregiver or family member in certain cases such as dementia were included. Patients not fulfilling the mentioned criteria were excluded.

During this project, a Medication review was conducted by two experienced clinical pharmacists over 12 months. Following the patient’s interview, an analysis of the patient’s medical treatment was performed. The analysis included the list of medications incorporating both those prescribed by the physician for the patient and any over-the-counter medications self-administered by the patient. Then, a formulation of justified pharmaceutical interventions was proposed for the patient’s general practitioner. After the physician’s approval, treatment modifications were communicated to the patient [28].

In the Original MGPIDP-L project, a sample size was calculated using Epi Info 7.2.5.0. For a total population size of around 600,000 Lebanese older adults, a confidence level of 99.9%, and a prevalence of 60% of inappropriate prescribing among the elderly population [31], 1083 patients were needed. Out of 1,038 patients involved in the study, 188 (18.11%) records were excluded due to incomplete, insufficient, or conflicting data. This left a sample of 850 patients enrolled with complete data during the 12-month inclusion period. In this study, we used this convenience sample for secondary analysis. Based on the following calculation: Using the G-Power software, version 3.0.10, this sample was sufficient to detect a calculated difference in fall rate of 0.0526, an alpha error of 5%, and a power of 80%. Given the expected fall rate of 0.05, 25 predictors could be included in the model.

Tool used and analysis performed

The data collected directly from the patients included information on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, chronic diseases, presence of geriatric syndromes including previous falls, medical treatment, and its management, tolerability, and compliance. The collected data were analyzed using a combination of both implicit and explicit approaches. The implicit criteria are based on the patient's global assessment while explicit criteria consist of predefined indicators of potentially inappropriate medication use in the geriatric population, established by expert consensus. To enhance the detection of potentially inappropriate drug prescriptions (PIDPs) and optimize medical prescribing, we utilized five distinct lists—Beers criteria, EU7-PIM, Laroche, STOPP/START, and STOPP/Frail [31,32,33,34,35]. Given the variation in PIDP prevalence based on the criteria employed and considering the diverse origins of medications in the Lebanese market, we combined these lists to increase the likelihood of PIDP detection. Two pharmacists assessed each medication taken by the patient to determine if it matched any of the criteria listed in the five sets. They also evaluated the appropriateness of each medication based on the patient's clinical condition and determined whether a pharmaceutical intervention should be recommended to the general practitioner. In the current study, the medical prescriptions of the included subjects were also analyzed to detect the presence of FRIDs according to the Swedish National Board of Health. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare defined FRID classes and further classified them into drug categories that cause a high risk of falling, orthostatic hypotension, and/or systemic hypotension [24].

Assessment and predictors of falls

The variable of interest “the previous fall” was self-reported by the study participants. In the questionnaire, participants were asked whether they had fallen at least once in the past 3 months. The period of 3 months was chosen to avoid bias due to memory loss and to associate the fall with medication use recorded at baseline [36, 37]. These subjects were compared with participants who had not fallen to identify variables associated with increased fall risk.

Potential risk factors for falls were divided into 3 categories:

-

Sociodemographic variables

Age (young old (65–74); middle-old (75–84); old-old (≥ 85)), biological gender, weight, living arrangement (patient lives alone, with a spouse, or with family), residence area (North Lebanon, Beirut, Mount Lebanon, Beqaa and South), and type of assistance needed (nurse, housekeeper, physical therapy). The choice of these forms of assistance was influenced by the Lebanese context, where hiring a housekeeper was feasible for many individuals prior to the economic downturn. This served as a significant alternative to nursing homes, particularly for families with members who go out to work or are residing abroad. Registered nurses are typically required for older adults with specific healthcare needs. Additionally, in instances of falls, patients needing specialized medical attention are often hospitalized in tertiary care facilities due to the increased expenses associated with home-based nursing care and rehabilitation.

-

Disease-related variables

Existing medical conditions and/or geriatric syndromes [38] (Frailty, urine incontinence, insomnia, daytime drowsiness, involuntary weight loss, loss of appetite).

-

Medication-related variables

Total number of PIDPs/medical prescriptions, presence of fall risk-increasing drugs (FRIDs)/medical prescriptions, and FRID classes used according to the Swedish National Board of Health [24], dichotomous questions related to the patient’s behavior toward his medical treatment. These questions covered various aspects such as medical treatment management (e.g., pill organizer usage, medication pick up, self-dependent medication management), prescription of drugs (e.g., perception of medication quantity, adaptability to lifestyle), stock management (e.g., medication availability, excess, sharing), preparation and administration challenges, medication utility, side effects, treatment follow up, and self-medication tendencies.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 26 was used to analyze the data. The dependent variable was the self-reported fall history (fallers vs. non-fallers). The chi-square test was used to assess bivariate associations between categorical variables and fall history. The student-independent t-test and Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney tests were used when appropriate to compare means between fallers and non-fallers for continuous variables (weight, total number of medications, total number of diseases, total number of identified (PIDPs)/prescriptions, and total number of (FRIDs)/prescription) after checking for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Given the exploratory nature of our analysis, we opted not to adjust for multiple testing in the bivariate analyses as an initial step to identify variables that might warrant further investigation in subsequent multivariate analyses.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent factors associated with a fall in the past 3 months using a backward likelihood ratio method. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. To mitigate the risk of chance findings due to multiple tests, we applied the Bonferroni correction which adjusts the significance threshold for each test to maintain an overall experiment-wise error rate. The Hosmer & Lemeshow test was used to ensure sample adequacy. The evaluation of collinearity in our analysis was conducted by computing Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for each predictor variable incorporated in the different models. The main explanatory variables that were associated with fall in the bivariate analysis (p < 0.05) were included in the models to decrease potential confounding. Considering the case-to-independent variables (IVs) ratio of 40:1 [39], three consecutive regression models were conducted. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors variables from Table 1 were included in the first model. Medication-related variables from Tables 2, and 3 were introduced into the second model. The final model (model 3) was run with significantly associated variables from the previous two models as explanatory variables. The total number of drugs listed as FRID /prescription and the total number of PIDPs/prescription were also forced. In all cases, a P-value of less than 0.05, adjusted for the number of tests using the Bonferroni correction, was considered significant. This adjustment ensured a more conservative interpretation of statistical significance, guarding against inflated Type I error rates associated with multiple comparisons.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

In total, four hospitals (located in Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North and South) and ten community pharmacies (two in each region) participated in the study. 850 patients were included from the MGPIDP-L project. Of those, 166 (19.5%) had experienced a recent fall in the past three months. No difference between fallers and non-fallers was found in terms of age, gender, living arrangement, and residence area in our sample. However, fallers relied significantly more on different types of assistance when compared to non-fallers: 26.5%(n = 44) of them were helped by a housekeeper versus (vs.) 19.3%(n = 132) of non-fallers, 6.6% (n = 11) needed assistance of a registered nurse vs. 3.3% (n = 21) of non-fallers, and 7.8%(n = 13) necessitated physiotherapy sessions compared to 2.8%(n = 19) of non-fallers, Table 1.

Disease-related factors

Geriatric syndromes were more prevalent among fallers. 26.5% (n = 44) were frail and 47%(78) were dependent according to the Find survey [40]. Insomnia had a high overall prevalence in fallers, thus leading to experiencing more daytime drowsiness. 61.4%(n = 102) and 67.5% (n = 112) experienced insomnia and daytime drowsiness compared to 37.5%(n = 257) and 45.5% (n = 311) in non-fallers. Urinary incontinence was also more common among fallers (35.2%(n = 58) vs. 20.7%(n = 142)). Loss of appetite was more frequent in fallers (48.2%(n = 80) vs.18.5%(n = 127)) as well as weight loss (39.8%(n = 66) vs. 20.3%(n = 139)), Table 1.

Our results showed that fallers suffered from a higher number of diseases than non-fallers. The most frequent diseases among fallers and non-fallers were hypertension, followed by diabetes and dyslipidemia. Osteoporosis (29.8% (n = 48). vs. 16.8%(n = 115)), depression (15.7%(n = 26) vs. 9.8%(n = 67)), Alzheimer’s disease or dementia (6.6% (n = 11) vs. 1.5%(n = 10)), and epilepsy (4.8%(n = 8) vs. 1.6%(n = 11)) were significantly higher in fallers than non-fallers, Table 1.

Medication-related variables

Patient’s medical treatment management

Fallers depended more on assistance to take their own medical treatment (63%(n = 104) of fallers vs. 47%(n = 319) of non-fallers). 68% (n = 113) of them needed assistance with medication collection from the pharmacy compared to 57%(n = 387) of non-fallers. The management of drug stock was also a problem that was more detected among fallers. 15.7%(n = 26) of them would run out of medications from time to time vs. 10.2% (n = 70) in non-fallers. 21% (n = 35) of fallers felt that their medication’s schedule was not adapted to fit their lifestyle compared to 14%(n = 96) of non-fallers. However, self-medication was less frequent among fallers (13.3% (n = 22) vs. 22.5%(n = 154)), Table 2.

Analysis of medical prescriptions

In total, 396 FRIDs were identified for the 166 fallers and 1423 FRIDs for 684 non-fallers. Among drugs affecting the central nervous system, antipsychotics (7.3% (n = 12) vs. 3.5%(n = 24)) and antidepressants (15.7% (n = 26) vs. 9.2%(n = 63)) were significantly more prescribed for fallers compared to non-fallers. Since they affect the central nervous system, they increase the chances of imbalance and falls in the participants.

In addition, drugs causing orthostatic hypotension were frequently prescribed in our sample for both groups (86.3%(n = 342) in fallers vs.89.38%(n = 1272) in non-fallers). Anti-adrenergic hypertensives (C02) (7.8% (n = 13) vs. 3.2%(n = 22)) and beta-blockers (61.4%(n = 102) vs. 51.1%(n = 350)) were significantly more used in fallers. On the contrary, vasodilators prescribed in the treatment of cardiac diseases were less frequent among fallers (3.6%(n = 6) in fallers vs. 9.8%(n = 67) in non-fallers), Table 3.

However, no significant differences were found between fallers and non-fallers in terms of the total number of medications per prescription classified as FRIDs nor in the total number of identified drug-related problems, Table 3.

Multivariate analysis

The multivariate analysis was done in three consecutive models as described in Table 4.

In the first model, statistically significant predictors for sociodemographic and disease-related factors with a corrected Bonferroni p-value of 0.0033 were: functional dependence, loss of appetite, and drowsiness.

In the second model, the use of beta-blockers increased the risk of falls. Self-dependent medication management was negatively associated with falls. In contrast, patients who ran out of medication from time to time were more likely to fall. The adjusted P-value after the Bonferroni correction for model 2 was 0.0055.

The final model (Model 3) showed that having experienced a fall in the last three months was significantly associated with several risk factors considering an adjusted Bonferroni P-value of 0.0055. Loss of appetite increased the odds of falling by 3 (ORa = 3.020, CI [2.074–4.397]). The risk of fall almost tripled for dependent subjects (ORa = 2.877, CI [1.787–4.632]) and, it was doubled for patients suffering from drowsiness (ORa = 2.093, CI [1.440–3.043]). Among the FRIDs, using beta-blockers increased the odds of falling by 1.9 (ORa = 1.943, CI [1.339–2.820]), Table 4.

Discussion

In our study population, 19.5% of the patients had experienced a fall in the three months prior to the medication review. The study found that loss of appetite and dependency were significant predictors of falls. Drowsiness was also identified as risk factor. Beta-blocker use predisposed to falls in the last three months.

Our study showed that loss of appetite is the most significant predictor of falls among Lebanese older adults. Poor appetite has been reported in the literature as a predictor of malnutrition. Nutritional status in older adults is a key predictor of both frailty and sarcopenia [41,42,43]. The decrease in daily energy intake leads to weight loss, disproportionate loss of lean body tissue, and reduced muscle strength. These outcomes render older adults at higher risk of imbalances and falls [44]. Recently published studies discuss a possible association between polypharmacy, weight loss, and malnutrition [45,46,47,48,49]. This could be explained by the fact that certain drugs have been proven to affect taste, smell, or salivation, which may lead patients to change their patterns of food or fluid intake [50]. In our study, medications causing taste disturbances were the most prevalent in patients who experienced falls such as diuretics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, Table 3 [51]. Early detection of the loss of appetite can help to prevent falls and improve overall health outcomes in older adults. These findings highlight the importance of addressing the loss of appetite as a critical risk factor for falls in the Lebanese elderly population.

In the context of our study's findings, the observed two-fold higher risk of falls in dependent individuals reaching the stage of disabled frailty aligns with the established understanding that frailty as a clinical geriatric syndrome [52, 53] contributes significantly to vulnerability in the elderly. This vulnerability, in turn, heightens the risk of adverse outcomes including dependency, disability, falls, and increased mortality [54]. Notably, our results emphasize the importance of considering the specific disability associated with frailty as a crucial factor influencing the risk of falls among older adults.

While previous literature has consistently highlighted that frail older adults exhibit the highest risk of falls, followed by prefrail older adults [55], our study provides additional nuance by indicating that the disability aspect of frailty appears to play a pivotal role in determining the risk of falls. This nuanced understanding contributes valuable insights into the intricate relationship between frailty, disability, and the propensity for falls among the elderly population.

As demonstrated in previous findings [56], drowsiness was also among the geriatric syndromes that were found to be associated with falls. This result can be explained by the fact that there’s a common use of medications that cause sleep disturbances among fallers [31, 57,58,59,60,61]. Drugs that affect the brain (antidepressants and antipsychotics) and some antihypertensive agents (adrenergic antihypertensives and beta-blockers) were frequently used in fallers. It may be necessary to consider alternative medications, modify dosages, or monitor side effects to reduce the risk of falls in older adults who are taking such medications.

When we examined the subclasses of FRIDs, we found that only beta-blockers increased the likelihood of falls. This could be explained by the fact that this drug class can increase the risk of orthostatic hypotension and imbalances leading to falls. In our study, selective and nonselective beta-blockers were more frequently prescribed than other FRID classes, possibly influencing our findings. Nonselective β-blockers could be related to fall risk because of their broader spectrum of action and their potentially negative effect on skeletal muscle. Conflicting results regarding the effects of beta-blockers on falls have been previously published [21, 62,63,64], and deprescribing FRIDs in isolation has not been shown to reduce falls in older adults in previous meta-analyses [65]. This may be due to the variability among patients and the multifactorial nature of falls [66,67,68]. Our data suggest that exploring and intervening on a broad range of risk factors including the personalization of pharmacologic treatment is likely necessary to help reduce falls in older adults.

This study had many strengths. Overall, it has a robust methodology, with a detailed statistical analysis that allows the identification of significant predictors of falls among Lebanese community-dwelling older adults. The findings provide valuable information for healthcare professionals in identifying risk factors for falls and implementing customized interventions tailored to individual needs to reduce the risk of falls. Furthermore, the study examined the occurrence of falls within the three months prior to the medication review. While this timeframe may restrict comparisons to international studies, as a duration of 12 months is commonly used, it can mitigate the risk of bias due to memory loss. We included several factors that have not been studied in the literature that may influence the risk of falls, such as behavioral factors. There are several well-studied approaches to fall prevention that either target a single risk factor or focus on multiple risk factors [25,26,27] but none examine patient behaviors towards their medical treatment. Although patient behaviors were not significantly associated with fall risk in multivariate analysis, this was the first article to address how patients manage their medications in terms of their provision, preparation, or follow-up. In addition, this study included all Lebanese regions, which improves the external validity of our findings. The study is a foundation for further research and will prove essential to the implementation of various plans to control the risk of falls among Lebanese older adults.

The limitations of the study include the questionnaire that didn’t take into consideration all potential risk factors of falls, such as environmental hazards, injuries associated with falls, and the number of previous falls. In addition, it was not possible to correlate the information obtained from the patients with the physician’s medical records due to the challenges of accessing such records in the Lebanese health system. The one-time medication review may not accurately capture the cause-effect relationship between drugs and falls, making it difficult to determine with certainty whether the falls happened before or while using the medication. The list of medications used to identify FRIDs may not be complete and uniform and may not highlight differences between pharmacological subclasses. The study did not consider testing for interactions like the combined effect of disease and medical treatment and excluded participants taking less than 5 drugs which may lead to selection bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of addressing various risk factors for falls in Lebanese older adults, including loss of appetite, dependency, drowsiness, and specific medications such as beta-blockers. Customized interventions may help prevent falls and improve overall health outcomes in addition to performing continuous medication reviews and analysis of medical prescriptions. Finally, the identification of these factors allows the recognition of the groups that are most susceptible to the occurrence of this outcome and consequently offers important support for the elaboration and planning of Lebanese government policies, actions, and strategies to address this serious public health problem.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper, its supporting information file, and on the repository Zenodo at the following 10.5281/zenodo.6321171.

Abbreviations

- ADE:

-

Adverse drug events

- FRID:

-

Fall risk increasing drugs

- PIDP:

-

Potentially inappropriate drug prescribing

- MGPIDP-L:

-

Management of potentially inappropriate drug prescribing in Lebanon

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- P:

-

Power

References

Qin Z, Baccaglini L. Distribution, determinants, and prevention of falls among the elderly in the 2011–2012 California health interview survey. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(2):331–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100217.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, & Population Division. (2017). World population ageing: 2017 highlights. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf.

Salari N, Darvishi N, Ahmadipanah M, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M. Global prevalence of falls in the older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2022;17(1):334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-022-03222-1.

Boulos C, Salameh P, Barberger-Gateau P. The AMEL study, a cross sectional population-based survey on aging and malnutrition in 1200 elderly Lebanese living in rural settings: Protocol and sample characteristics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):573. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-573.

Almawlawi E, Al Ansari A, Ahmed A. (2011). Prevalence and Risk Factors for Falls Among the Elderly in Primary Healthcare Centers (PHC) in Qatar. Qatar Medical Journal, 2011(1). https://doi.org/10.5339/qmj.2011.1.7.

Assiri EH, Assiri MH, Alsaleem SA. Epidemiology of falls among elderly people attending primary healthcare centers in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. World Family Med J/Middle East J Family Med. 2020;18(2):47–59. https://doi.org/10.5742/MEWFM.2020.93766.

Guidelines WF. (n.d.). World Falls Guidelines. World Falls Guidelines. Retrieved January 8, 2024, from https://worldfallsguidelines.com/.

Pluijm SMF, Smit JH, Tromp EAM, Stel VS, Deeg DJH, Bouter LM, Lips P. A risk profile for identifying community-dwelling elderly with a high risk of recurrent falling: results of a 3-year prospective study. Osteoporosis Int. 2006;17(3):417–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-0002-0.

Zhang L, Ding Z, Qiu L, Li A. Falls and risk factors of falls for urban and rural community-dwelling older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):379. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1391-9.

World Health Organization, World Health Organization. Ageing and Life Course Unit, 2008. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. World Health Organization. (n.d.).

Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x.

Smith EM, Shah AA. Screening for geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):55–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2017.08.002.

Le K, Chou E, Boyce RD, Albert SM. Fall risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and falls among low-income community-dwelling older adults. Innovation in Aging. 2021;5(1):igab001. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab001.

Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E, Mcinnes E, Horton K. A systematic review of older people’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls-prevention interventions. Ageing Soc. 2008;28(4):449–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006861.

Huang AR, Mallet L, Rochefort CM, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R. Medication-related falls in the elderly: causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(5):359–76. https://doi.org/10.2165/11599460-000000000-00000.

Chung JY. Geriatric clinical pharmacology and clinical trials in the elderly. Transl Clin Pharmacol. 2014;22(2):64–9. https://doi.org/10.12793/tcp.2014.22.2.64.

Tan JL, Eastment JG, Poudel A, Hubbard RE. Age-related changes in hepatic function: an update on implications for drug therapy. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(12):999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-015-0318-1.

Chen Y, Zhu L-L, Zhou Q. Effects of drug pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties, characteristics of medication use, and relevant pharmacological interventions on fall risk in elderly patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:437–48. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S63756.

SciELO - Brazil—Chronic kidney disease and the aging population Chronic kidney disease and the aging population. (n.d.). Retrieved July 14, 2022, from https://www.scielo.br/j/jbn/a/Yh9RsTbnS3qcKTT5HJ7hLRF.

Correa-Pérez A, Delgado-Silveira E, Martín-Aragón S, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Fall-risk increasing drugs and recurrent injurious falls association in older patients after hip fracture: a cohort study protocol. Therapeu Adv Drug Safety. 2019;10:204209861986864. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098619868640.

de Vries M, Seppala LJ, Daams JG, Van de Glind EMM, Masud T, van der Velde N, Blain H, Bousquet J, Bucht G, Caballero-Mora MA, van der Cammen T, Eklund P, Emmelot-Vonk M, Gustafson Y, Hartikainen S, Kenny RA, Laflamme L, Landi F, Masud T, van der Velde N. Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Cardiovascular drugs. J American Med Directors Assoc. 2018;19(4):371.e1-371.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.013.

Seppala LJ, van de Glind EMM, Daams JG, Ploegmakers KJ, de Vries M, Wermelink AMAT, van der Velde N, Blain H, Bousquet J, Bucht G, Caballero-Mora MA, van der Cammen T, Eklund P, Emmelot-Vonk M, Gustafson Y, Hartikainen S, Kenny RA, Laflamme L, Landi F, van der Velde N. Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: III. Others. J American Med Directors Assoc. 2018;19(4):372.e1-372.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.099.

Seppala LJ, Wermelink AMAT, de Vries M, Ploegmakers KJ, van de Glind EMM, Daams JG, van der Velde N, Blain H, Bousquet J, Bucht G, Caballero-Mora MA, van der Cammen T, Eklund P, Emmelot-Vonk M, Gustafson Y, Hartikainen S, Kenny RA, Laflamme L, Landi F, van der Velde N. Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Psychotropics. J American Med Directors Assoc. 2018;19(4):371.e11-371.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.098.

Fastbom J, Schmidt I. (n.d.). Indikatorer för god läkemedelsterapi hos äldre. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, 106.

Bou Malham C, El Khatib S, Cestac P, Andrieu S, Rouch L, Salameh P. Impact of pharmacist-led interventions on patient care in ambulatory care settings: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):e14864. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14864.

Ming Y, Zecevic AA, Hunter SW, Miao W, Tirona RG. Medication review in preventing older adults’ fall-related injury: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Canadian Geriatr J. 2021;24(3):237–50. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.24.478.

Lavan AH, Gallagher P. Predicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults. Therapeu Adv Drug Safety. 2016;7(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098615615472.

Bou Malham C, El Khatib S, Cestac P, Andrieu S, Rouch L, Salameh P., C. (n.d.). Management of potentially inappropriate drug prescribing among Lebanese patients in primary care settings -the MGPIDP-L project: Description of an interventional prospective non-randomized study. PLOS ONE.

Ismail RA, Sibai RHE, Dakessian AV, Bachir RH, Sayed MJE. Fall related injuries in elderly patients in a tertiary care centre in Beirut, Lebanon. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020;13(2):142. https://doi.org/10.4103/JETS.JETS_84_19.

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):187–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x.

Malham CB, Khatib SE, Strumia M, Andrieu S, Cestac P, Salameh P. The MGPIDP-L project: potentially inappropriate drug prescribing and its associated factors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;109:104947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2023.104947.

By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: 2019 AGS beers criteria® update expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767.

Ml L, Jp C. (n.d.). Liste de médicaments potentiellement inappropriés à la pratique médicale française. 11.

Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thürmann PA. The EU(7)-PIM list: A list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(7):861–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1860-9.

Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C, O’Mahony D. STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy): Consensus validation. Age Ageing. 2017;46(4):600–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx005.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2014;44(2):213–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu145.

Lawlor DA. Association between falls in elderly women and chronic diseases and drug use: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327(7417):712–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7417.712.

Ziere G, Dieleman JP, Hofman A, Pols HAP, van der Cammen TJM, Stricker BHCh. Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61(2):218–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02543.x.

Srinivasan R, Lohith CP, Srinivasan R, Lohith CP. Main study—detailed statistical analysis by multiple regression. Strategic marketing and innovation for Indian MSMEs. Singapore: Springer; 2017. p. 69–92.

Vittinghoff et al. - Regression Methods in Biostatistics.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://cds.cern.ch/record/1499230/files/9781461413523_TOC.pdf.

Frailty.net. (2016, February 23). A self-reported screening tool for detecting community-dwelling older persons with frailty syndrome in the absence of mobility disability: The FiND questionnaire. Frailty. https://frailty.net/frailty-toolkit/diagnostic-tools/a-self-reported-screening-tool-for-detecting-community-dwelling-older-persons-with-frailty-syndrome-in-the-absence-of-mobility-disability-the-find-questionnaire-2/.

Esquivel MK. Nutritional assessment and intervention to prevent and treat malnutrition for fall risk reduction in elderly populations. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(2):107–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617742847.

Fávaro-Moreira NC, Krausch-Hofmann S, Matthys C, Vereecken C, Vanhauwaert E, Declercq A, Bekkering GE, Duyck J. Risk factors for malnutrition in older adults: a systematic review of the literature based on longitudinal data. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(3):507. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.011254.

Ülger Z, Halil M, Kalan I, Yavuz BB, Cankurtaran M, Güngör E, Arıoğul S. Comprehensive assessment of malnutrition risk and related factors in a large group of community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(4):507–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.006.

Weiss EP, Jordan RC, Frese EM, Albert SG, Villareal DT. Effects of weight loss on lean mass, strength, bone, and aerobic capacity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(1):206–17. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001074.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(5):514–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.2116.

Jyrkkä J, Mursu J, Enlund H, Lönnroos E. Polypharmacy and nutritional status in elderly people. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834d155a.

Fabian E, Bogner M, Kickinger A, Wagner K-H, Elmadfa I. Intake of medication and vitamin status in the elderly. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;58(2):118–25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000327351.

Rahi B, Daou T, Gereige N, Issa Y, Moawad Y, Zgheib K. Effects of polypharmacy on appetite and malnutrition risk among institutionalized lebanese older adults—preliminary results. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(Supplement_2):69–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa040_069.

Heuberger RA, Caudell K. Polypharmacy and nutritional status in older adults: a cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(4):315–23. https://doi.org/10.2165/11587670-000000000-00000.

Douglass R, Heckman G. Drug-related taste disturbance: a contributing factor in geriatric syndromes. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien. 2010;56(11):1142–7.

Doty RL, Shah M, Bromley SM. Drug-induced taste disorders. Drug Safety. 2008;31(3):199–215. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831030-00002.

Cesari M, Demougeot L, Boccalon H, Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, Vellas B, Andrieu S. A self-reported screening tool for detecting community-dwelling older persons with frailty syndrome in the absence of mobility disability: the FiND questionnaire. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101745.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A Biolog Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

Frailty in Older People. (2013). Lancet, 381(9868), 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9.

Cheng M-H, Chang S-F. Frailty as a risk factor for falls among community dwelling people: evidence from a meta-analysis: falls with frailty. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(5):529–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12322.

Brassington GS, King AC, Bliwise DL. Sleep problems as a risk factor for falls in a sample of community-dwelling adults aged 64–99 years. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(10):1234–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02596.x.

Glab KL, Wooding FGG, Tuiskula KA. Medication-related falls in the elderly: mechanisms and prevention strategies. Consult Pharm. 2014;29(6):5.

Chang C-H, Yang Y-HK, Lin S-J, Su J-J, Cheng C-L, Lin L-J. Risk of insomnia attributable to β-blockers in elderly patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28(1):53–8. https://doi.org/10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-12-rg-004.

Doghramji PP. Detection of insomnia in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 10):18–26.

CV Drugs That Negatively Affect Sleep Quality. (n.d.). American College of Cardiology. Retrieved January 16, 2022, from https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2014/07/18/15/46/http%3a%2f%2fwww.acc.org%2flatest-in-cardiology%2farticles%2f2014%2f07%2f18%2f15%2f46%2fcv-drugs-that-negatively-affect-sleep-quality.

Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, Marra CA. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1952–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357.

Zang G. Antihypertensive drugs and the risk of fall injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2013;41(5):1408–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060513497562.

Ham AC, van Dijk SC, Swart KMA, Enneman AW, van der Zwaluw NL, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, van Schoor NM, Zillikens MC, Lips P, de Groot LCPGM, Hofman A, Witkamp RF, Uitterlinden AG, Stricker BH, van der Velde N. Beta-blocker use and fall risk in older individuals: original results from two studies with meta-analysis: beta-blocker use and fall risk in older people. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(10):2292–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13328.

Lee J, Negm A, Peters R, Wong EKC, Holbrook A. Deprescribing fall-risk increasing drugs (FRIDs) for the prevention of falls and fall-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e035978. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035978.

Ageing and health. (n.d.). Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

Ungar A, Rafanelli M, Iacomelli I, Brunetti MA, Ceccofiglio A, Tesi F, Marchionni N. Fall prevention in the elderly. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2013;10(2):91–5.

Phelan EA, Mahoney JE, Voit JC, Stevens JA. Assessment and management of fall risk in primary care settings. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(2):281–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.004.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the staff of the Haroun Hospital, Makassed Hospital, Saint Therese Hospital, and Mazloum Hospitals for their help and cooperation in access to patients and treatment charts during the study period.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Sarah El Khatib, Philippe Cestac. Data handling: Sarah El Khatib, Carmela Bou Malham. Statistical analysis: Sarah El Khatib, Carmela Bou Malham. Methodology and Supervision: Pascale Salameh, Philippe Cestac. Validation: Philippe Cestac, Pascale Salameh, Sandrine Andrieu. Writing – original draft: Sarah El Khatib. Review & editing: Carmela Bou Malham, Pascale Salameh, Philippe Cestac, Sandrine Andrieu, Mathilde Strumia.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of INSPECT-LB under the number of 2021REC-001-INSPECT-09–04.

The study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the international standards pertaining to protection of human research subjects.

A informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khatib, S.E., Malham, C.B., Andrieu, S. et al. Fall risk factors among poly-medicated older Lebanese patients in primary care settings: a secondary cross-sectional analysis of the “MGPIDP-L project”. BMC Geriatr 24, 327 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04951-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04951-0