Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have shown that sarcopenia was associated with depression among older adults. However, most of these investigations used a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to establish a causal relation, the present study examined whether sarcopenia was associated with incident depressive symptoms.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study with participants from the Western China Health and Aging Trends (WCHAT) study. Participants could complete anthropometric measurements and questionnaires were included. The exposure was sarcopenia, defined according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia in 2019, the outcome was depressive symptoms, evaluated by GDS-15. We excluded depression and depressive symptoms at baseline and calculated the risk of incident depressive symptoms during the follow-up year.

Results

A total of 2612 participants (mean age of 62.14 ± 8.08 years) were included, of which 493 with sarcopenia. 78 (15.82%) participants with sarcopenia had onset depressive symptoms within the next year. After multivariable adjustment, sarcopenia increased the risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.651, 95%CI = 1.087–2.507, P = 0.0187) in overall participants. Such relationship still exists in gender and sarcopenia severity subgroups. Low muscle mass increased the risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.600, 95%CI = 1.150–2.228, P = 0.0053), but low muscle strength had no effect (RR = 1.250, 95%CI = 0.946–1.653, P = 0.117).

Conclusions

Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms, Precautions to early detect and targeted intervene for sarcopenia should continue to be employed in adult with sarcopenia to achieve early prevention for depression and reduce the incidence of adverse clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcopenia is an age-related disease characterized by progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, muscle strength, and/or physical function. Sarcopenia is prevalent among older adults and is associated with a wide variety of adverse outcomes, such as frailty, falls, disability, and mortality [1]. Recent studies have found that sarcopenia is also related to depression [2]. Aging, physical inactivity and dysregulated levels of inflammatory cytokines or hormones in sarcopenia may be risk factors for depression [3, 4]. Depression is one of the most important causes of emotional distress in later life, significantly reducing quality of life and becoming one of the major diseases contributing to the global disease burden [5].

The latest meta-analysis identified a higher prevalence of depression among sarcopenia patients than in the general population and revealed a significant association between sarcopenia and depression [6]. However, all included studies were cross-sectional in design and could not establish a causal relationship between sarcopenia and depression, and the degree of sarcopenia was not graded in almost all studies, so the effect of varying severity of sarcopenia on the risk of depression is unclear.

Therefore, we examined the association between sarcopenia and incident depressive symptoms among older adults without preexisting depressive symptoms in western China. Furthermore, we examined the association between sarcopenia and incident depressive symptoms among subgroups stratified by baseline age, gender, sarcopenia severity and sarcopenia diagnostic components. This prospective cohort study can confirm the effect of sarcopenia on the risk of depression and provide a theoretical basis for sarcopenia prognosis research and depression risk factor screening in the future.

Methods

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee (approval: 2017 − 445) and all subjects signed informed consent forms, and the cohort study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study setting and population

This was a one-year prospective cohort study, the baseline survey was done from July to December 2018 and follow-up information was obtained from July to December 2019 [7].

Participants were from the Western China Health and Aging Trends (WCHAT) study [7]. Participants with 50 years and older and could completed a body composition test, handgrip strength test, 4-meter walking test, and questionnaires were included into the cohort [7]. Participants who had baseline depression and depressive symptoms as assessed by the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15), severe malnutrition, cancer, or > 5% weight change in the last 3 months were excluded.

Exposure

The primary exposure was sarcopenia, defined as loss of skeletal muscle mass plus loss of muscle strength and/or reduced physical performance according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia in 2019 (AWGS 2019) criteria [8], and defined participants with low muscle mass, low muscle strength and low physical performance as having “severe sarcopenia.” Muscle mass was assessed by bioimpedance analysis (BIA) using a Body Composition Analyzer (Inbody 770, BioSpace, Seoul, Korea) [9]. Low muscle mass was defined as skeletal muscle mass index (SMMI) less than 7.0 kg/m2 for men and less than 5.7 kg/m2 for women [8]. Muscle strength was assessed by hand strength using a hand-held dynamometer (EH101; Camry, Zhongshan, China). Low muscle strength was defined as a grip strength of less than 28 kg for men and less than 18 kg for women [8]. Physical performance was assessed by usual gait speed over a 4-meter course. Low physical performance was defined as a usual gait speed of less than 1.0 m/s for both sexes [8].

Outcomes

The primary outcome was depressive symptoms and was assessed by GDS-15, which was a commonly used screening tool for depression among older adults [10]. The GDS-15 has been found to be highly correlated with the original GDS in the Chinese population, and the reliability and validity of this scale have been established [11]. Participants with a score of ≥ 5 were classified as having depressive symptoms [12].

Covariates

Demographic information included age, sex, marital status (single, married, divorced), educational level (illiteracy, bachelor’s degree or below, and bachelor’s degree or above), occupation (manual labor and other), and whether they lived alone. The height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) of all the participants were recorded. Healthy lifestyle factors included smoking (yes/no), alcohol use (heavy (0.75 g per day), light, and no drinking). Chronic diseases diagnosed by medical institutions, including cancer, heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic liver disease (CLD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), which were reported by participants or their caregivers. Major trauma and acute illness in the last three months were recorded. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess the sleep quality in the last month, scores of 16–21 were defined as poor sleep quality [13]. Cognitive status was assessed using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ), scores of 0–2 were categorized as normal cognitive function; scores of 3–10 were categorized as cognitive function impairment [14]. Physical disability was assessed using the Barthel index activity of daily living (ADL), and ADL disability was defined as having difficulty in ≥ 1 ADL (defecation, urination, grooming, toileting, eating, transferring, moving, dressing, stairs, bathing) [15]. Social support survey was used Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), which including 10 items across three dimensions: objective support, subjective support and the utilization of support, the total score was the summary of scores for each item, the higher the score was, the better the social support status [16].

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics are presented using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables among the entire sample and by baseline sarcopenia status. We used a t test to compare continuous variables and a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables between persons with and without sarcopenia.

We calculated the risk of incident depressive symptoms during the follow-up year among participants with and without sarcopenia and used a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables between the two groups.

Using univariate analysis to find depressive symptoms and its related factors, then a multicollinearity diagnostic was conducted by calculating the values of tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) [17]. The values of tolerance > 0.1 and VIF < 10 were used to indicate the absence of multicollinearity among the dependent variables [17].

Subsequently, we used generalized linear regression models to examine the unadjusted and adjusted associations between sarcopenia and incident depressive symptoms. The adjustment variables incorporated those variables that were considered significant in the univariate analysis. Furthermore, we performed subgroups analysis stratified by baseline gender, age (< 60 years and ≥ 60 years), sarcopenia severity (sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia) and sarcopenia diagnostic components (low muscle mass and low muscle strength) using the same methods as above.

The statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data management and analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

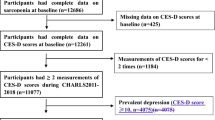

About 4426 participants completed a body composition test, handgrip strength test, 4-m walking test, and depression assessment. We excluded participants who had baseline depression and depressive symptoms (n = 877), severe malnutrition or cancer (n = 59), and > 5% weight change in the last 3 months (n = 81). A total of 3409 participants were included at baseline in 2018, and we then excluded participants who were lost to follow-up data (n = 751) and had major trauma or acute illness in the last 3 months at follow-up assessment (n = 46) in 2019 (Fig. 1).

Ultimately, a total of 2612 participants (mean age of 62.14 ± 8.08 years) were analyzed in this study, including 493 patients with sarcopenia and 2119 nonsarcopenia controls. There were differences in age, gender, BMI, skeletal muscle mass, grip strength, walking speed, divorce, widowhood, illiteracy, smoking, cognitive impairment, disability, social support between the two groups, the demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

The sarcopenia group included 424 older people (≥ 60 years old) (Supplementary Table S1), 234 male participants (Supplementary Table S2) and 253 participants with severe sarcopenia (Supplementary Table S3)). A total of 575 participants with low muscle mass and 980 with low muscle strength in this study (Supplementary Table S4).

Given that 22% of the participants were not followed up after one year, we further compared baseline characteristics with and without follow-up data (Supplementary Table S5). The prevalence of sarcopenia and important confounders did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Incidence of depression after one-year follow-up

At the one-year follow-up, 78 (15.82%) participants with sarcopenia had onset depressive symptoms. The incidence of depressive symptoms was 10.05% for male participants with sarcopenia, 14.55% for female participants with sarcopenia, 16.75% for older participants with sarcopenia (≥ 60 years old), and 15.42% for participants with severe sarcopenia. 85 (17.78%) participants with low muscle mass and 142 (14.49%) participants with low muscle strength had onset depressive symptoms (Table 2).

Risk ratios of Sarcopenia to depressive symptoms

In all participants, sarcopenia increased the risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.330, 95%CI = 1.041-1.700, P = 0.0226) after adjusting for age and gender, and after adjusting for important confounding factors, sarcopenia increased the risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.651, 95%CI = 1.087–2.507, P = 0.0187) (Table 3).

After adjusting for important confounding factors, sarcopenia did not increase the risk of depressive symptoms in participants < 60 years old (RR = 1.169, 95%CI = 0.523–2.609, P = 0.7040). Sarcopenia increased the risk of depressive symptoms in participants ≥ 60 years old (RR = 1.792, 95%CI = 1.219–2.633, P = 0.0030), as well as in male participants (RR = 1.651, 95%CI = 1.087–2.507, P = 0.0187) and female participants (RR = 1.792, 95%CI = 1.219–2.633, P = 0.0030). In sarcopenia severity subgroup, both nonsevere sarcopenia (RR = 1.520, 95%CI = 1.072–2.376, P = 0.0464) and severe sarcopenia (RR = 1.746, 95%CI = 1.108–2.680, P = 0.0107) increased the risk of depressive symptoms.

Low muscle mass did not increase the risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.213, 95%CI = 0.956–1.539, P = 0.1122) after adjusting for age and gender, but after adjusting for important confounding factors, low muscle mass increased the risk of depressive symptoms RR = 1.600, 95%CI = 1.150–2.228, P = 0.0053). However, low muscle strength could not increase the risk of depressive symptoms after adjusting for age and gender (RR = 1.163, 95%CI = 0.945–1.433, P = 0.1547) or important confounding factors (RR = 1.250, 95%CI = 0.946–1.653, P = 0.117).

Discussion

The results of this study clearly confirmed the causal relationship between sarcopenia and depressive symptoms. Sarcopenia increased the risk of depressive symptoms onset among the older population in western China, as well as in old population and sarcopenia severity subgroups. Compared with muscle strength, low muscle mass was more significant in the risk of depressive symptoms.

The overall prevalence of depression in sarcopenia patients was 0.28 and the overall adjusted odds ratio (OR) between sarcopenia and depression was 1.57 in our recent meta-analysis. In our cohort study, the onset of depressive symptoms in sarcopenia patients was 15.82% overall and 16.71% in patients aged ≥ 60 years, slightly higher than the longitudinal study by Chen et al. [18], which is the only longitudinal study on the incidence of sarcopenia and depressive symptoms to date, showing that the annual incidence of depressive symptoms over the course of the 1-year follow-up was 12.0% for people over the age of 60 years and sarcopenia was significantly associated with depressive symptoms incidence (OR = 3.57, 95% CI = 1.59–8.04). While, in our study sarcopenia was associated with 46.5% higher risks of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.465, 95% CI = 1.141–1.880). These differences are likely due to differences between study populations, varying ethnic characteristics and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia. In that study, sarcopenia was defined according to the AWGS 2014 criteria and severe sarcopenia was not distinguished.

Studies on the association between muscle mass and muscle strength and depression have been inconsistent. Some studies considered low muscle mass and low muscle strength to be significantly and independently associated with depression, [19] some reported that depression was not associated with low muscle mass but was associated with low muscle strength, [20] and others indicated that depression was significantly correlated with muscle strength but not with muscle mass [21]. However, all the above studies had cross-sectional designs. Fukumori et al. [22] used data from the Locomotive Syndrome and Health Outcomes in the Aizu Cohort Study (LOHAS), and multivariate random-effects logistic analysis revealed that participants with lower grip strength at baseline had higher odds of developing depressive symptoms one year later. Cao’s prospective cohort study including 1,094 participants indicated no significant relationship between baseline grip strength and the risk of developing depressive symptoms during a one-year follow-up period [23]. Our findings are consistent with Chen’s reported that muscle mass rather than muscle strength was associated with new onset depressive symptoms [18]. These differences may be due to the different diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia and depression, differences between the study populations and different ethnic characteristics.

Several mechanisms may be involved in the association between sarcopenia and depression. First, skeletal muscle cells secrete various myokines to regulate their mass and function. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a myokine that can cross the blood-brain barrier [24] and is involved in the regulation of neuronal and glial development, neuroprotection, and synaptic interactions [25], several studies have reported decreased serum and plasma BDNF levels in patients with depression [26]. In addition, age-related chronic low-grade inflammation is an important cause of sarcopenia, and low levels of inflammation and oxidative stress also playing a role in depression [27, 28]. Sarcopenia may adversely affect mental function through metabolic and endocrine mechanisms, skeletal muscle is the main organ of glucose homeostasis, and 75% of postprandial glucose intake is completed by skeletal muscle. Low muscle mass may impair glucose homeostasis, and various studies have shown that there is a correlation between blood glucose homeostasis and depression [29]. Disability and insufficient physical activity due to decreased muscle strength and muscle mass may be a cause of depression [30].

This study has several advantages. This was a large, prospective cohort study with rigorous quality control, rigorous assessment of sarcopenia and depressive symptoms, and a complete analysis of sarcopenia diagnostic components on depressive symptoms risk. Despite extensive efforts to curb study limitations, some limitations exist. First, with a follow-up period of only one year, we did not examine the long-term relationship between sarcopenia and depressive symptoms. Second, the attrition rate of follow-up was relatively high, but adults who were lost to follow-up had a similar baseline health status to those who completed follow-up, and incident depressive symptoms should not be affected by missing data. Third, in this study, BIA was used to diagnose low muscle mass, rather than dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) or CT, which are inconvenient to perform in large sample surveys in communities and rural areas, and BIA is also recommended as one of the diagnostic methods in AWGS 2019. Finally, our study did not exclude older adults with dementia/cognitive impairment, and GDS assessment results for depressive symptoms may be inadequate for participants with cognitive problems.

Conclusions

Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for depressive symptoms, as well as in old population and sarcopenia severity subgroups. Compared with muscle strength, low muscle mass was more significant in the risk of depressive symptoms.

In future clinical studies, precautions to early detect and targeted intervene for sarcopenia should continue to be employed in adult with sarcopenia to achieve early prevention for depression and reduce the incidence of adverse clinical outcomes.

For future research, long-term and large-scale prospective cohort studies with different ages and regions are required to verify the effect of sarcopenia on depression.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the data needs further analysis, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WCHAT:

-

Western China health and aging trends

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- AWGS:

-

Asian working group for sarcopenia

- BIA:

-

Bioimpedance analysis

- SMMI:

-

Skeletal muscle mass index

- GDS:

-

Geriatric depression scale

- ADL:

-

Activity of daily living

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- DEXA:

-

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

References

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA, Sarcopenia. Lancet (London England). 2019;393(10191):2636–46.

Kim NH, Kim HS, Eun CR, et al. Depression is associated with Sarcopenia, not central obesity, in elderly Korean men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2062–8.

Budui SL, Rossi AP, Zamboni M. The pathogenetic bases of Sarcopenia. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015;12(1):22–6.

Hallgren M, Herring MP, Owen N, et al. Exercise, Physical Activity, and sedentary behavior in the treatment of Depression: broadening the Scientific perspectives and Clinical opportunities. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:36.

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet (London England). 2006;367(9524):1747–57.

Li Z, Tong X, Ma Y, Bao T, Yue J. Prevalence of depression in patients with Sarcopenia and correlation between the two diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(1):128–44.

Hou L, Liu X, Zhang Y, et al. Cohort Profile: West China Health and Aging Trend (WCHAT). J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(3):302–10.

Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–7e2.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(4):601.

Cruice M, Worrall L, Hickson L. Reporting on psychological well-being of older adults with chronic aphasia in the context of unaffected peers. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(3):219–28.

Chau J, Martin CR, Thompson DR, Chang AM, Woo J. Factor structure of the Chinese version of the geriatric Depression Scale. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(1):48–59.

Lim PP, Ng LL, Chiam PC, et al. Validation and comparison of three brief depression scales in an elderly Chinese population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(9):824–30.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–41.

Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(2):61–3.

Liu JW, Fu-Ye LI, Lian YL. Investigation of reliability and validity of the social support scale. Journal of Xinjiang Medical University; 2008.

Marcoulides KM, Raykov T. Evaluation of Variance inflation factors in regression models using Latent Variable modeling methods. Educ Psychol Meas. 2019;79(5):874–82.

Chen X, Guo J, Han P, et al. Twelve-Month incidence of depressive symptoms in Suburb-Dwelling Chinese older adults: role of Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(1):64–9.

Jin Y, Kang S, Kang H. Individual and Synergistic Relationships of Low Muscle Mass and Low Muscle Function with Depressive Symptoms in Korean Older Adults. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(19).

Hayashi T, Umegaki H, Makino T, et al. Association between Sarcopenia and depressive mood in urban-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(6):508–12.

Chen L, Sheng Y, Qi H, et al. Correlation of Sarcopenia and depressive mood in older community dwellers: a cross-sectional observational study in China. BMJ open. 2020;10(9):e038089.

Fukumori N, Yamamoto Y, Takegami M, et al. Association between hand-grip strength and depressive symptoms: Locomotive Syndrome and Health outcomes in Aizu Cohort Study (LOHAS). Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):592–8.

Cao J, Zhao F, Ren Z. Association between changes in muscle strength and risk of depressive symptoms among Chinese female College students: a prospective cohort study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:616750.

Pan W, Banks WA, Fasold MB, Bluth J, Kastin AJ. Transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor across the blood-brain barrier. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37(12):1553–61.

Kowiański P, Lietzau G, Czuba E, et al. BDNF: a key factor with multipotent impact on Brain Signaling and synaptic plasticity. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2018;38(3):579–93.

Zhou C, Zhong J, Zou B, et al. Meta-analyses of comparative efficacy of antidepressant medications on peripheral BDNF concentration in patients with depression. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0172270.

Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200.

Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Williams LJ, et al. Association of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein with de novo major depression. Br J Psychiatry: J Mental Sci. 2010;197(5):372–7.

DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):157–63.

Brach JS, FitzGerald S, Newman AB, et al. Physical activity and functional status in community-dwelling older women: a 14-year prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(21):2565–71.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from theSichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0295, 2022YFG0205), 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence at West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC21005), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022ZDZX0021),Health Research of Cadres in Sichuan province (SCR2022-101). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Z L and J Y. Acquisition of data: Z L, B L, X T, Y M, T B. Analysis and interpretation of data: Z L and B L. Drafting of the manuscript: Z L. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J Y and C W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University Ethical Committee (approval: 2017 − 445) and all subjects signed informed consent forms.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

: Characteristics of the participants at baseline in subgroups

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Liu, B., Tong, X. et al. The association between sarcopenia and incident of depressive symptoms: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 24, 74 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04653-z