Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis is a prevalent condition in older adults that leads to reduced physical function in many patients and ultimately requires hip or knee replacement. The aim of the study was to determine the impact of hip and knee arthroplasty on the physical performance of orthogeriatric patients with osteoarthritis.

Methods

In this prospective study, we used data from 135 participants of the ongoing Special Orthopaedic Geriatrics (SOG) trial, funded by the German Federal Joint Committee (GBA). Physical function, measured by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), was assessed preoperatively, 3 and 7 days postoperatively, 4–6 weeks and 3 months after hip and knee arthroplasty. For the statistical analysis, the Friedman test and post-hoc tests were used.

Results

Of the 135 participants with a mean age of 78.5 ± 4.6 years, 81 underwent total hip arthroplasty and 54 total knee arthroplasty. In the total population, SPPB improved by a median of 2 points 3 months after joint replacement (p < 0.001). In the hip replacement group, SPPB increased by a median of 2 points 3 months after surgery (p < 0.001). At 3 months postoperatively, the SPPB increased by a median of 1 point in the knee replacement group (p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Elective total hip and knee arthroplasty leads to a clinically meaningful improvement in physical performance in orthogeriatric patients with osteoarthritis after only a few weeks.

Trial registration

This study is part of the Special Orthopaedic Geriatrics (SOG) trial, German Clinical Trials Register DRKS00024102. Registered on 19 January 2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is considered the most prevalent chronic joint disease in the world and one of the most common causes of pain and disability in older people [1]. About half of the world’s population aged 65 years and older is affected by OA [2]. 80% of people with symptomatic OA have limited mobility, while 25% are unable to carry out normal daily activities [3, 4]. Several studies have also found an association between OA and frailty [5, 6]. Reduced mobility is part of the frailty syndrome. With the increasing incidence of OA, more and more older people are facing severe financial and social burdens [3]. Therefore, prevention and treatment of OA must be a high priority in health and socioeconomic policy.

The prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with age because the disease is not reversible. OA of the hip and knee is a major cause of impaired physical performance and disability, especially in older people [3]. Increasing symptoms and loss of joint function often lead to hip or knee replacement surgery. Due to demographic trends, the number of primary hip and knee arthroplasties will increase dramatically in the coming years. For example, the number of elective total hip and total knee arthroplasties (THA and TKA) in the US is expected to increase by 71% and 85% respectively by 2030 [7].

The aim of surgical joint replacement is to restore joint function and thus reduce pain and improve mobility as well as restore social participation according to the World Health Organization (WHO) model of disability. There is a large body of literature on functional recovery after hip and knee replacement, but it is often based on younger patients and uses the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) to assess mobility [8, 9]. However, little is known about the increase in physical performance in orthogeriatric patients after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty as measured by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). It is a commonly used, validated test of physical function in geriatrics. SPPB evaluates balance, mobility and muscle strength by examining an individual’s ability to stand in different positions, time to walk 4 m, and time to rise up from and sit down on a chair 5 times [10]. So far, only a pilot study with four patients has investigated the feasibility and acceptability of the SPPB as a clinically applicable, simple and objective test to assess physical function in older adults after joint replacement [11].

In Germany, total hip and knee arthroplasty are among the 20 most common surgical procedures for hospitalised patients overall [12]. The aim of the study was to determine the impact of elective total hip and knee arthroplasty on the physical performance of older adults with OA. We hypothesised that hip and knee joint replacement in orthogeriatric patients would be associated with an improvement in physical performance as measured by the SPPB.

Methods

Study design

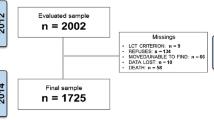

This study is part of the ongoing Special Orthopaedic Geriatrics (SOG) trial (German Clinical Trials Register, 19/01/2021, DRKS00024102). The SOG study is a monocentric, prospective, randomised controlled trial funded by the German Federal Joint Committee (GBA). The original study aimed to investigate a specially developed multimodal care model (SOG care model) for orthogeriatric patients with total hip and total knee arthroplasty compared to usual orthopaedic care without orthogeriatric co-management. Physical performance as measured by the SPPB was the primary outcome measure. A detailed description of the study can be found elsewhere [13]. The current study enrolled 145 patients from the SOG trial between 01April 2021 and 15 April 2023. This additional analysis was not planned when the original study was designed.

Data collection

In the Orthopaedics Department of our University Centre, about 18,000 patients are treated annually in the university outpatient clinic and > 1,500 endoprosthetic procedures on hip and knee joints are performed each year. Participants were recruited at the university outpatient clinic if they were diagnosed with primary hip or knee osteoarthritis and had an indication for THA or TKA. The study data were collected preoperatively (t1), 3 and 7 days postoperatively (t2 and t3), 4–6 weeks (t4) and 3 months (t5) after surgery.

Study population

Eligibility criteria included: primary hip or knee osteoarthritis, age ≥ 70 years and multimorbidity or age ≥ 80 years and indication for elective unilateral hip or knee replacement. Exclusion criteria were age < 70 years, previous bony surgery or tumour in the area of the joint to be treated, acute infection and increased need for care (care level ≥ 4; severe impairment of independence, need for help with basic care 24 h a day).

Out of a total of 145 subjects in the SOG study, there were 10 drop-outs. The reasons were cancellation of surgery or refusal to participate in the study. As a result, the number of people included in the analysis was 135. In 5 participants, SPPB could not be performed on postoperative days 3 and 7. The number of patients lost to follow-up was 8 at 4–6 weeks (follow-up 1) and 8 at 3 months (follow-up 2).

Surgical techniques and implants

All operations were performed in a single Department of Orthopaedic Surgery of a University Medical Centre. The lateral decubitus position was used for the THA. A minimally invasive anterolateral approach was chosen [14]. Press-fit acetabular components and stems from a single manufacturer (Pinnacle cup, Corail stem; DePuy, Warsaw, IN) were used in all THAs. Cementless stems were preferred. Knee arthroplasty was performed via a medial parapatellar approach. Cemented components from a single manufacturer (PFC Sigma; DePuy) were used in all TKAs. Patella resurfacing was not performed. All patients were mobilised under full weight bearing immediately after surgery. Postoperatively, patients with THA and TKA remained in hospital for 7 days unless complications occurred. They received daily physiotherapy and were then discharged to inpatient rehabilitation. With a few exceptions, outpatient rehabilitation was performed at the patient’s request. Most patients were transferred to the rehabilitation clinic belonging to the hospital. The duration of inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation was three weeks.

Assessment of physical performance

Physical performance was measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), a commonly used and validated assessment in geriatrics that includes three objective tests of lower body function [8]. SPPB evaluates balance, mobility and muscle strength by examining an individual’s ability to stand in different positions, time to walk 4 m, and time to rise up from and sit down on a chair 5 times. The individual tests are scored between 0 and 4, with a maximum total score of 12 (range 0–12). Higher total scores indicate better lower body function [10, 15]. Small meaningful changes in the SPPB are present at 0.5 points, substantial changes are assumed from a 1-point improvement [16].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including demographic and morbidity-related characteristics were calculated for the whole sample. As a core statistical method, the non-parametric Friedman test was employed, as an alternative to the one-way repeated measures ANOVA. The Friedman test was preferred due to the scale and distribution of the outcome variable. It was tested whether there were significant differences between the five times of measurement, with the SPPB score being the dependent variable of interest. Medians and interquartile ranges were reported for each time of measurement alongside the respective p-values yielded by the Friedman test. Post-hoc tests were then performed for significant differences comparing all of the time points against each other using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. In this procedure Bonferroni-correction was applied to reduce the risk of a type I error. Effect sizes and p-values will be reported for each comparison. Further analyses included Friedman tests as well as post-hoc tests for hip replacement surgery patients and knee replacement surgery patients separately as well as for each of the three subscores (standing balance, 4 m gait speed test, and the timed five-repetition sit-to-stand test) of the SPPB. Taking into account the drop-outs and patients lost to follow-up described under study population, the following number of patients were available for the analyses: t1: n = 135, t2: n = 130, t3: n = 130, t4: n = 127, t5: n = 127. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.1. using the package using the R-package “rstatix”. p-values p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of a total of 135 participants, 81 patients underwent total hip arthroplasty and 54 patients underwent total knee arthroplasty. The female gender was represented more frequently overall (65.2%). The mean age of all participants was 78.5 ± 4.7 years, in the hip replacement group it was 78.1 ± 4.5 years and in the knee replacement group 79.1 ± 4.8 years. All study participants had a mean of 7.6 ± 2.9 comorbidities. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) for the total population was 5.3 ± 1.8 and the overall mean PFP (Physical Frailty Phenotype) score was 2.1 ± 1.3. (Table 1).

Using the Friedman test, we first examined whether there were significant differences between the five measurement points of the SPPB score. In the total sample as well as in the hip and knee arthroplasty groups, there were significant differences (p < 0.001) between at least two of the SPPB values measured perioperatively at 5 different time points (Table 2).

Total study group

Patients had intermediate to low physical performance preoperatively with a median SPPB score of 7 (IQR 5–9). On postoperative day 3, there was a significant decrease in the SPPB score to a median of 4 (p < 0.001). After three months, the median SPPB in the total population improved by 2 points (p < 0.001) compared to the baseline median (Fig. 1; Table 3).

Hip arthroplasty group

The hip patients had already returned to their pre-surgery baseline on postoperative day 7 (hospital discharge) with a median score of 7. After 4–6 weeks, the SPPB even increased by 2 points (from a baseline value of 7 to a value of 9) (p = 0.005). After 3 months, the median SPPB remained 9 (Tables 2 and 3).

Knee arthroplasty group

The decrease in SPPB was particularly pronounced in the knee arthroplasty group, from a median score of 8 preoperatively to a median of 4 postoperatively (p < 0.001). In this cohort, the baseline SPPB was not reached with a median value of 6 on day 7 after surgery. This was only the case 4–6 weeks after surgery. After 3 months, the median SPPB in the knee group improved by 1 point (p = 0.003) compared to the baseline median (Fig. 1; Table 3).

Figure 2 describes the differences in the SPPB subscores standing balance, 4-meter gait speed test (4MGS) and 5 times sit to stand test (5STS) between the five different measurement points (t1-t5). The Friedman test showed significant differences in all three subscores between the five measurement points (Supplementary Table 1). With the exception of the knee replacement group in the balance subscore, all other groups improved by a median of one point between preoperative assessment and measurement 3 months after surgery.

Discussion

In our study, SPPB increased by 2 points 3 months after THA and by 1 point 3 months after TKA. Perera et al. considered a change in the SPPB total score of 0.5 points as a small significant change. A change in the SPPB of 1.0 points or more is assumed to be a substantial change [16]. This means that after both elective THA and TKA, there is a substantial improvement in the physical performance of orthogeriatric patients with OA 3 months after surgery. In line with the results of Perera et al. [16], the SPPB score decreased in the first days after surgery, but returned to baseline by postoperative day 7 in the total population (hospital discharge). The THA group demonstrated substantial improvement in SPPB 4–6 weeks postoperatively (discharge from rehabilitation). The TKA group showed substantial improvement in SPPB 3 months after surgery.

To assess physical performance, the SPPB is commonly used in geriatrics in both clinical and research contexts [10]. Przkora et al. evaluated the applicability and acceptability of SPPB before and after TKA in 2021 [11]. The results indicated that SPPB is easy to perform and can be easily integrated into daily clinical practice. Although the study only investigated SPPB in knee replacement, Przkora et al. concluded that assessing SPPB in the perioperative setting in patients undergoing lower extremity joint replacement surgery is feasible and acceptable [11]. The SPPB is therefore an objective test for the simple assessment of physical function in older adults undergoing elective TKA and THA with known high reliability, validity and responsiveness. As a measure of postoperative functional outcome, the SPPB has mainly been studied and used in patients undergoing cardiac or pulmonary surgery [17, 18].

SPPB is correlated with sarcopenia, frailty, disability and mortality [15, 19,20,21]. It is possible that all these factors can be improved after THA and TKA. OA of the hip and knee is a significant barrier to physical activity and is one of the top five causes of disability in American adults [22]. According to Guralnik et al., increasing physical function can lead to the prevention of severe, especially mobility-related, disabilities on the one hand, and promote recovery from disabilities on the other [15]. A 1-point improvement in the SPPB summary score has been indicated as clinically meaningful and correlated well with increases in overall activity and survival [15]. In their review, de Fátima Ribeiro Silva et al. reported numerous studies in which lower SPPB scores (range 0–6 points) were associated with a significantly increased risk of death [23]. In addition, SPPB is related to activities of daily living (ADLs), falls, dyspnoea, postoperative complications, cardiovascular disease, institutionalisations and hospitalisations [23].

Compared to non-surgical interventions, THA and TKA seems superior in improving physical performance in older patients with OA and multimorbidity. In a cluster randomised trial comparing two community-based programmes, Zgibor et al. showed an improvement in SPPB of 0.3 and 0.5 points respectively after 6 months [24]. In our study, participants’ SPPB scores improved by a median of 2.0 points at three months after surgical hip and knee replacement compared to preoperative baseline. The participants in the study by Zgibor et al. were younger (included age ≥ 50 years, mean age 72.7 ± 7,8 years). Also, arthritis was not defined more precisely and no severity was given, so mild forms of arthritis may have been included [24].

An alternative test often used in studies to assess mobility is the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) [25]. Compared to the SPPB [10], it is faster and allows the use of armrests. However, it always requires the patient to stand up. As long as standing up is not possible independently, progress in walking cannot be shown. The test is therefore susceptible to floor effects. In contrast, the SPPB is less vulnerable as a test battery [10]. The SPPB is a widely studied and well-validated tool with good test quality criteria and particularly good reliability. Studies identified good prognostic properties for functional deterioration, mortality, institutionalisations and duration of clinical treatments [10, 15, 19,20,21, 23]. Unnanuntana et al. and also Pongcharoen et al. demonstrated significantly shorter TUG test times after TKA at 3 months in their 2018 and 2023 studies [9, 26]. Although these studies were not conducted in orthogeriatric patients, their results are consistent with our demonstrated improvements in mobility with SPPB.

This study has some limitations. The study is part of the ongoing SOG trial and the analyses presented here were not originally planned. For this reason, there is no control group for this evaluation. Although the participants had exhausted all conservative measures (analgesics including opioids, physiotherapy and often rehabilitation) as a prerequisite for surgery, there are always circumstances that could have influenced physical performance even without special intervention. This may include, for example, psychosocial aspects or the treatment of comorbidities. The improvement in physical performance is not exclusively a benefit of the surgery. Post-operative care by the healthcare team, physiotherapy and rehabilitation for functional exercise after joint replacement also contribute. The results were observed in this context. The additional impact of orthogeriatric co-management is not clear, especially as such care models can be very heterogeneous. Prestmo et al. observed no significant difference between orthopaedic treatment and orthogeriatric co-management in the context of hip fractures in both SPPB and TUG within 1 month after surgery. Only at 4 months and 1 year did significant differences appear for SPPB, but not for TUG [27].

A major strength of this study is its prospective design with 135 participants. Apart from the pilot study by Przkora et al. with a total of 4 subjects [11], we are not aware of any other study on this issue. The mean age of the total population of this study is 78.5 ± 4.7 years. Many geriatric studies also accept significantly younger participants, sometimes from the age of 50. Furthermore, these are not only very old patients, but also multimorbid and often pre-frail/frail participants. The close collaboration between orthopaedists and geriatricians in the SOG study made it possible for the first time to address this issue using an established and validated geriatric assessment tool such as the SPPB. Although many participants had OA in other joints, which worsened in some patients in the further course after surgery, a considerable improvement in physical performance could still be achieved through THA or TKA. Data analysis was performed externally and independently by the Department of Health Economics at the Technical University of Munich.

Conclusion

Elective total hip and knee arthroplasty leads to a clinically meaningful improvement in physical performance in orthogeriatric patients with OA. With total hip replacements, there is a substantial increase in SPPB as early as 4–6 weeks after surgery. Knee replacement demonstrates substantial improvement in SBBP 3 months after surgery.

Data Availability

The data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CCI:

-

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- d:

-

Day

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- IQR:

-

Interquartile Range

- Md:

-

Median

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- mo:

-

months

- NRS:

-

Nutritional Risk Screening

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- p:

-

p-value

- PFP:

-

Physical Frailty Phenotype (Fried)

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SOG:

-

Special Orthopaedic Geriatrics

- SPPB:

-

Short Physical Performance Battery

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- TUG:

-

Timed Up and Go Test

- w:

-

week

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Li Y, Wei X, Zhou J, Wei L. The age-related changes in cartilage and osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:916530.

Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F, Lafeber FP. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2115–26.

Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):646–56.

Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022;30(2):184–95.

Misra D, Felson DT, Silliman RA, Nevitt M, Lewis CE, Torner J, Neogi T. Knee osteoarthritis and Frailty: findings from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study and Osteoarthritis Initiative. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(3):339–44.

Drey M, Wehr H, Wehr G, Uter W, Lang F, Rupprecht R, Sieber CC, Bauer JM. The frailty syndrome in general practitioner care: a pilot study. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;44(1):48–54.

Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg. 2018;100(17):1455–60.

Götz J, Maderbacher G, Leiss F, Zeman F, Meyer M, Reinhard J, Grifka J, Greimel F. Better early outcome with enhanced recovery total hip arthroplasty (ERAS-THA) versus conventional setup in randomized clinical trial (RCT). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-023-05002-w.

Pongcharoen B, Liengwattanakol P, Boontanapibul K. Comparison of Functional Recovery between Unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023;105(3):191–201.

Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scherr PA, Wallace RB. A short physical performance Battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):85–94.

Przkora R, Sibille K, Victor S, Meroney M, Leeuwenburgh C, Gardner A, Vasilopoulos T, Parvataneni HK. Assessing the feasibility of using the short physical performance Battery to measure function in the immediate postoperative period after total knee replacement. Eur J Transl Myol. 2021;31(2):9673.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Germany: The 20 most frequent surgeries of full inpatient hospital patients together. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Health/Hospitals/Tables/drg-surgeries-together.html (2023). Accessed 19 Jan 2023.

Kappenschneider T, Maderbacher G, Weber M, Greimel F, Holzapfel D, Parik L, Schwarz T, Leiss F, Knebl M, Reinhard J, Schraag AD, Thieme M, Turn A, Götz J, Zborilova M, Pulido LC, Azar F, Spörrer JF, Oblinger B, Pfalzgraf F, Sundmacher L, Iashchenko I, Franke S, Trabold B, Michalk K, Grifka J, Meyer M. Special orthopaedic geriatrics (SOG) - a new multiprofessional care model for elderly patients in elective orthopaedic Surgery: a study protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial of a multimodal intervention in frail patients with hip and knee replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1079.

Michel MC, Witschger P, MicroHip:. A minimally invasive procedure for total hip replacement Surgery A modified Smith-Petersen approach. Hip Int. 2006;3:40–7.

Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–61.

Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):743–49.

Ashikaga K, Saji M, Takanashi S, Nagayama M, Akashi YJ, Isobe M. Physical performance as a predictor of midterm outcome after mitral valve Surgery. Heart Vessels. 2019;34(10):1665–73.

Hanada M, Yamauchi K, Miyazaki S, Oyama Y, Yanagita Y, Sato S, Miyazaki T, Nagayasu T, Kozu R. Short-physical performance Battery (SPPB) score is associated with postoperative pulmonary Complications in elderly patients undergoing lung resection Surgery: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Chron Respir Dis. 2020;17:1479973120961846.

Cesari M, Landi F, Calvani R, Cherubini A, Di Bari M, Kortebein P, Del Signore S, Le Lain R, Vellas B, Pahor M, Roubenoff R, Bernabei R, Marzetti E, SPRINTT Consortium. Rationale for a preliminary operational definition of physical frailty and sarcopenia in the SPRINTT trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29(1):81–8.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M. Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older people 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31.

Mutambudzi M, Chen NW, Howrey B, Garcia MA, Markides KS. Physical performance trajectories and mortality among older Mexican americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(2):233–39.

Michaud CM, McKenna MT, Begg S, Tomijima N, Majmudar M, Bulzacchelli MT, Ebrahim S, Ezzati M, Salomon JA, Kreiser JG, Hogan M, Murray CJ. The burden of Disease and injury in the United States 1996. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:11.

de Fátima Ribeiro Silva C, Ohara DG, Matos AP, Pinto ACPN, Pegorari MS. Short physical performance Battery as a measure of physical performance and mortality predictor in older adults: a Comprehensive Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10612.

Zgibor JC, Ye L, Boudreau RM, Conroy MB, Vander Bilt J, Rodgers EA, Schlenk EA, Jacob ME, Brandenstein J, Albert SM, Newman AB. Community-based healthy aging interventions for older adults with arthritis and Multimorbidity. J Community Health. 2017;42(2):390–99.

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed up & go: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–8.

Unnanuntana A, Ruangsomboon P, Keesukpunt W. Validity and responsiveness of the two-Minute Walk Test for Measuring Functional Recovery after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(6):1737–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.015.

Prestmo A, Hagen G, Sletvold O, Helbostad JL, Thingstad P, Taraldsen K, Lydersen S, Halsteinli V, Saltnes T, Lamb SE, Johnsen LG, Saltvedt I. Comprehensive geriatric care for patients with hip fractures: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1623–33.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study used data from participants in the SOG trial. The SOG study was fully funded by the German Federal Joint Committee - GBA (Grant no. 01VSF19030 (SOG)) and the funding management was carried out by the German Aerospace Center. The funder played no role in the conception or execution of the study, data analyses or results reporting. The authors and their contributions to the manuscript are independent from the funder.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM, GM and TK originated the idea for the study and led on its design. MM and JG supervised the project. GM, FG, DH, TS, SP, JG, MS, KM and TK participated in the design of the study and were responsible for data acquisition. PB, MM and TK contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. PB provided statistical consultation. TK drafted the manuscript. MM, GM and PB revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is part of the SOG trial approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Regensburg (2020/06/24, No. 20-1837-101) and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. No financial compensation was offered for participation in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kappenschneider, T., Bammert, P., Maderbacher, G. et al. The impact of elective total hip and knee arthroplasty on physical performance in orthogeriatric patients: a prospective intervention study. BMC Geriatr 23, 763 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04460-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04460-6