Abstract

Background

Although several studies have reported the relationship between vision impairment (VI) and multimorbidity in high-income countries, this relationship has not been reported in low- and middle-income countries. This study aimed to explore the relationship between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions among the elderly Chinese population.

Methods

The cross-sectional analysis was applied to data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2018. A total of 8,108 participants ≥ 60 years old were included, and 15 chronic conditions were used in this study. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the relationship between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions.

Results

The prevalence of 15 chronic conditions and multimorbidity was higher among the elderly with VI than those without VI. After adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic confounders, 10 chronic conditions were associated with VI (all P < 0.05). Furthermore, positive association was observed between VI and one (odds ratio [OR]: 1.52; 95% confidence intervals [95%CI]: 1.16–2.00; P = 0.002), two (OR: 2.09; 95%CI: 1.61–2.71; P < 0.001), three (OR: 2.87; 95%CI: 2.22–3.72; P < 0.001), four (OR: 3.60; 95%CI: 2.77–4.69; P < 0.001), and five or more (OR: 5.53; 95%CI: 4.32–7.09; P < 0.001) chronic conditions, and the association increased as the number of chronic conditions (P for trend < 0.001). Sensitivity analysis stratified by gender, education, smoking status, and annual per capita household expenditure still found VI to be positively associated with multimorbidity.

Conclusions

For patients older than 60 years, VI was independently associated with multimorbidity and various chronic conditions. This result has important implications for healthcare resource plans and clinical practice, for example, increased diabetes and kidney function screening for patients with VI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multimorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions affecting the same individual [1], has become a public health disaster worldwide. It was estimated that more than half of the worldwide population older than 60 years has multimorbidity [2]. Chronic conditions, especially multimorbidity, are associated with decreased quality of life, impaired functional status, poor physical and mental health, and increased mortality [3,4,5,6,7]. As the population rapidly ages, multimorbidity’s public health impact will increase, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Vision impairment (VI) is also a common condition correlated with aging, and it is among the most disabling chronic conditions for the elderly population. In 2020, about 1.1 billion people suffered from VI worldwide [8], and this number is expected to rise to 1.7 billion by 2050 [8]. Studies have reported that VI and chronic conditions often co-occur [9,10,11]. Additionally, when combined with VI, chronic conditions significantly affect daily functioning and social participation, while VI may aggravate chronic conditions [12, 13]. Therefore, clarifying the association between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions is critical. Such an understanding would contribute to the coordinated healthcare resources plan, thus improving medical practice and care services.

However, most previous studies have focused on the relationship between VI and a single chronic disease. For example, studies have found associations between VI and diabetes, heart disease, cognitive decline, and stroke [14,15,16,17]. Few studies have reported on the association between VI with comprehensive chronic conditions and multimorbidity [18,19,20], and these studies have been conducted in high-income countries. Up to date, no studies have reported on the relationship between VI and multimorbidity in low- and middle-income countries, which may be limited relevance by differences in prevalence and progression rates, the risk factors for VI and chronic conditions, and cultural, lifestyle, environmental, and socioeconomic factors. This relationship is important in low- and middle-income countries, which bear 80% of the global burden of chronic conditions [21], and limited healthcare resources.

Accordingly, the current study aimed to determine the association between VI with multimorbidity and 15 chronic conditions among the elderly Chinese population (≥ 60 years old), using nationally representative survey data pertaining to the world’s largest elderly population of 264 million [22].

Method

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was conducted using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The CHARLS protocol and population have been described in detail previously [23]. In brief, CHARLS collects high-quality data through face-to-face interviews and structured questionnaires from a nationally representative sample of Chinese residents aged 45 years and older, and its sample is selected using multistage, stratified, proportional-to-scale probability. CHARLS conducted a baseline survey in 2011, which included 17,708 respondents from 450 villages or resident communities in 28 of the 31 provincial-level administrative divisions in mainland China. CHARLS followed up with these participants every two years, and three follow-ups were conducted in 2013, 2015, and 2018, respectively. The CHARLS program’s protocol followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015). All participants signed an informed consent form before completing the survey.

In the current study, we used these 2018 data (which included 19,816 participants) to analyze the association between VI and multimorbidity. To focus on age-related VI, we included participants who were aged 60 years and older in our analysis. Participants with missing data on vision, depressive symptoms, or any of the chronic conditions were excluded from this study. Figure 1 is a flowchart depicting the study’s selected participants. The final sample included 8,108 participants with and without VI.

Defining vision impairment

A self-report assessment of visual function identified VI in the CHARLS data. Participants were asked two questions related to vision impairment: (1) How good is your eyesight for seeing things at a distance, like recognizing a friend from across the street (with glasses or corrective lenses if you wear them)? (2) How good is your eyesight for seeing things up close, like reading ordinary newspaper print (with glasses or corrective lenses if you wear them)? Responses to these questions were “poor,” “fair,” “good,” “very good,” and “excellent”. Participants whose responses were “poor” eyesight for seeing things at a distance or up close were classified as VI in the current study.

Defining chronic conditions and multimorbidity

We used 15 chronic conditions to measure multimorbidity in this study. Each participant was asked to report whether they had been diagnosed with any of the following chronic conditions by a physician: hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic lung disease, digestive system diseases, liver disease, kidney disease, asthma, arthritis, and memory-related diseases. The standardized questionnaire assessed chronic conditions in Table S1. Hearing loss was defined as a patient having (a) had hearing problems, (b) worn a hearing aid, or (c) self-reported their hearing status as poor (rather than excellent, very good, good, or fair). Participants with depressive syndrome or emotional, neurological, or mental problems were defined as having psychiatric diseases. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 10-item Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) was used to assess [24], and participants with the CESD-10 ≥ 10 were defined as having depressive symptoms. Emotional, neurological, or mental problems were from self-reported questions. Multimorbidity was defined as the presence of ≥ 2 chronic conditions in the same person [1].

Covariates

The CHARLS questionnaire collected data on participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. These data included age, gender (male or female), residence (rural or urban), marital status (married or partnered versus single or widowed), education levels (primary school or below versus middle school or above), smoking status (current smoker, former smoker, or never having smoked), drinking status (current drinker, former drinker, or never having drunk), and health insurance status (insure or uninsured). Previous studies have confirmed that per capita household consumption expenditure reflects living standards better than household income [25]. Therefore, we used annual per capita household expenditure levels to assess participants’ economic situation. We divided per capita household consumer spending into three groups by tertiles.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the continuous variables’ normal distribution. The normally distributed variables were represented using means ± standard deviations (SDs), while the non-normally distributed continuity variables were represented by medians (interquartile ranges). The categorical variables were represented using their number (percentage). An independent-sample t-test or chi-square test was used to compare participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Two logistic regression models were used to calculate the relationship between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions. Model 1 adjusted for age and gender. Meanwhile, Model 2 further adjusted for residence, marital status, education levels, smoking status, drinking status, health insurance, and annual per capita household expenditure levels. To validate the results’ robustness, we performed a sensitivity analysis stratified by gender, education levels, smoking, and per capita household consumption levels. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (Version 17.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). All p values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 8,108 participants aged over 60 years enrolled in this study. Participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Their average age was 68.0 ± 6.1 years, and 48.7% were male. The number of participants with VI stood at 2,541 (31.3%). Generally, compared to the participants without VI, the participants with VI were older and more likely to be female, rural residents, single or widowed, never smoked or drank, and did not have health insurance (all P < 0.05). Additionally, the participants with VI had lower education levels and annual per capita household expenditure than those without VI (all P < 0.001).

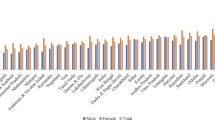

Prevalence of multimorbidity and chronic conditions among people with or without VI

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the prevalence of multimorbidity and chronic conditions among participants with and without VI. Of the participants with VI, 95.8% had at least one chronic condition, compared to 87.5% among the participants without VI (P < 0.001). Participants without VI had a higher prevalence of one or two chronic conditions than those with VI (19.6% vs. 11.0% for one condition; 20.9% vs. 15.7% for two conditions). Also, the participants with VI had a higher prevalence of four, or five or more chronic conditions than those without VI (16.2% vs. 12.3% for four conditions; 35.1% vs. 17.6% for five or more conditions). Furthermore, participants with VI had a higher prevalence of the 15 chronic conditions we considered than those without VI, but no statistical difference was observed for cancer (P = 0.181). The greatest difference in prevalence between the participants with VI and without VI was observed for hearing loss (31.2% vs. 10.7%) and psychological diseases (52.4% vs. 32.1%).

Association between VI with Multimorbidity and chronic conditions

Table 3 shows the association between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions. After adjusting for age and gender, VI was found to positively correlate with multimorbidities (all P < 0.001) and chronic conditions (all P < 0.05) except for cancer (P = 0.239). After further adjusting for the other potential confounders, this result showed that patients with VI were significantly positively associated with one (odds ratio [OR]: 1.52; 95%CI: 1.16–2.00; P < 0.001), two (OR: 2.09; 95%CI: 1.61–2.71; P < 0.001), three (OR: 2.87; 95%CI: (2.22–3.72; P < 0.001), four (OR: 3.60; 95%CI: 2.77–4.69; P < 0.001), and five or more (OR: 5.53; 95%CI: 4.32–7.09; P < 0.001) chronic conditions, and this association increased with the number of chronic conditions (P for trend < 0.001). Additionally, VI was independently associated with 10 chronic conditions: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, digestive disease, arthritis, asthma, hearing loss, memory-related disease, and psychological diseases (all P < 0.05). Among these conditions, hearing loss (OR: 3.19; 95%CI: 2.78–3.67; P < 0.001) and psychological diseases (OR: 1.65; 95%CI: 1.47–1.85; P < 0.001) were the most strongly associated with VI.

Sensitivity analysis

To consider the potential implications of participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, we performed sensitivity analyses stratified by gender, education level, smoking status, and annual per capita household expenditure. The results showed that VI remained significantly associated with multimorbidity (Tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

Using nationally representative data on the older Chinese population, this study showed that patients with VI experience a higher prevalence of multimorbidity and chronic conditions than those without VI. After adjusting for residence, marital status, education levels, smoking status, drinking status, health insurance, and annual per capita household expenditure levels, we found that VI was independently associated with multimorbidity and various chronic conditions, and this association increased with the number of chronic conditions. Additionally, this association was not influenced by gender, educational levels, smoking status, or annual per capita household expenditure. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the relationship between VI with multimorbidity and extensive chronic conditions in low- and middle-income countries.

This study analyzed the association between VI with extensive chronic conditions and multimorbidity, highlighted the cumulative effect of chronic conditions. Court et al. reported a significant association between VI and multimorbidity [18]. However, this study did not fully correct for demographic and socioeconomic confounders. Furthermore, a National Health Interview Survey in the United States found that patients with four patterns of multimorbidity group had a higher risk of VI compared with the healthy group [20]. This current study first analyzed the relationship between VI with multimorbidity in low- and middle-income countries, and we have corrected for potential confounding factors and performed sensitivity analysis. Our study provides robust evidence for the relationship between VI and multimorbidity. In addition, our results showed a stronger relationship between VI and multimorbidity compared with two previous studies in high-income countries [18, 19], which may be related to harder access to healthcare in low-and middle-income countries. However, this relationship’s underlying mechanism remains unclear. The accumulation of multiple deficits and the interaction between multiple domains may be important factors in the high risk of adverse health outcomes [26]. Therefore, individuals with multiple chronic conditions are more likely to develop VI due to the accumulated risk caused by pathological pathways such as vascular damage, neurodegeneration, inflammatory response, and immunity.

This study showed that the association between VI and multimorbidity is stronger among women. An important reason may be gender inequality in health insurance and health care; women have less health insurance and are less likely to receive health care than men [27, 28]. Studies also confirmed that persons with females are more susceptible to VI [29, 30]. In addition, chronic conditions and VI are bidirectional causal associations [31]. The above reasons may prompt this association to be stronger in women. Our result also showed that individuals with lower education levels are more likely to have VI, which may be that they are less likely to have health insurance or healthcare and worse health conditions [32, 33].

Previous studies have reported that VI is associated with specific chronic conditions [14,15,16, 34]. Our study shows that stroke and VI are associated, consistent with previous clinical studies [17, 35]. Further, the current population study confirms that patients with stroke should conduct visual function assessments. We also found strong associations between arthritis and VI. Arthritis is a common autoimmune disorder associated with sight-threatening ocular diseases such as uveitis, keratitis, and corneal melts [36]. Moreover, patients with arthritis usually use long-term corticosteroid therapy, and studies confirmed that corticosteroids are a risk factor for glaucoma and cataracts [37, 38]. Moreover, VI often co-occurs in elderly patients with hearing loss, and both diseases were considered important barriers to physical activity in low-and middle-income countries [39]. Therefore, good health services are needed for patients with VI and hearing loss to improve their health status and quality of life. At present, mental problems are a great global public health concern, and our study showed a 0.6-fold increased risk of psychological disorders in patients with VI, consistent with previous reports [40, 41], which reminds the whole society and family to pay attention to the mental health of patients with VI.

The causal relationship between VI and chronic conditions is complex. The Lancet Global Health Commission recently presented integrative evidence regarding the relationship between VI and chronic conditions [31]. The commission proposed that some chronic conditions cause VI, including diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia [42,43,44]. Additionally, VI and chronic conditions may share common risk factors. For example, drinking alcohol is associated with systemic diseases (such as liver, digestive, and cardiovascular diseases) [45], as well as ocular abnormalities (such as diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and glaucoma) [46]. Importantly, VI and chronic conditions can be linked by mediating factors likely limited physical activity, reduced access to health care, and increased social isolation [31], leading indirectly to or exacerbating chronic conditions.

Mortality due to chronic conditions accounts for three-quarters of all global deaths, with low- and middle-income countries accounting for 77% [47]. Therefore, to cope with the burden of multimorbidity, the healthcare systems should transform from a single-disease model to a more effective management multimorbidity model. Clinical guidelines have developed in the United States and Europe [48, 49], emphasizing patient-centered healthcare for older adults with multimorbidity. This current study showed that 85% of patients with VI Combined with multimorbidity. Previous studies have confirmed that VI, combined with chronic conditions, influences patients’ health status and quality of life significantly more than one condition alone [9, 50]. Additionally, studies have suggested that patients with VI have less access to healthcare than those without VI [51, 52]. Therefore, for patients who have both VI and systemic conditions, especially multimorbidity, clinicians should pay more attention to their healthcare services to improve their physical status. However, the current study did not analyze the healthcare utilization and health expenditure of patients with both VI and multimorbidity or chronic conditions, and these elements require further research.

This study has several strengths. First, it is the first nationally representative study to explore the association between VI with multimorbidity and 15 chronic conditions among the Chinese population. Second, this study adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic confounding factors and explored whether gender, education levels, smoking, and annual per capita household expenditure altered the association between VI and multimorbidity. Nonetheless, this study also faced several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study determining the association between VI with multimorbidity and chronic conditions, it has not established causes or effects, and longitudinal studies are needed to clarify causality. Second, although previous studies have shown that self-reporting is satisfactory for chronic conditions compared to physician diagnoses [53], self-reporting may have recall and other biases, which might have underestimated chronic conditions’ prevalence. Third, although we corrected potential confounders such as age, gender, education levels, etc., other residual confounders may not be included in our study. In addition, we may have included non-confounding in this analysis. Finally, the CHARLS visual function assessment was conducted using a visual acuity questionnaire rather than objectively measured. Although previous studies have confirmed that self-reported visual acuity is a good indicator of overall visual function and a strong association between self-reported visual acuity and objective measurements [54, 55], some discrepancies may exist.

Conclusion

In this study, we found a higher prevalence of chronic conditions among elderly Chinese patients with VI than those without VI. Furthermore, VI was independently associated with multimorbidity, and this association was found to increase with the number of chronic conditions. These results indicate that VI often coexists with multiple chronic health conditions in low- and middle-income countries, patients with multimorbidity will benefit from eye care, and this will improve the healthcare system’s efficiency. This has important implications for the healthcare services plan and clinical practice.

Data Availability

All data collected in the CHARLS are maintained at the National School of Development of Peking University, Beijing, China. The datasets are available from https://charls.pku.edu.cn/pages/data/111/zh-cn.html.

References

van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent Diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(5):367–75.

Chowdhury SR, Chandra Das D, Sunna TC, Beyene J, Hossain A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;57:101860.

Dugravot A, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, et al. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: a 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e42–e50.

Makovski TT, Schmitz S, Zeegers MP, Stranges S, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;53:100903.

Palladino R, Tayu Lee J, Ashworth M, Triassi M, Millett C. Associations between multimorbidity, healthcare utilisation and health status: evidence from 16 European countries. Age Ageing. 2016;45(3):431–5.

Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya U, Jain K, et al. The impact of multimorbidity on adult physical and mental health in low- and middle-income countries: what does the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) reveal? BMC Med. 2015;13:178.

Aubert CE, Kabeto M, Kumar N, Wei MY. Multimorbidity and long-term disability and physical functioning decline in middle-aged and older americans: an observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):910.

Blindness GBD. Vision impairment, vision loss expert group of the global burden of Diseases: Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e130–43.

Crews JE, Chou CF, Sekar S, Saaddine JB. The prevalence of chronic conditions and poor health among people with and without vision impairment, aged >/=65 years, 2010–2014. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:18–30.

Jones GC, Crews JE, Danielson ML. Health risk profile for older adults with blindness: an application of the International classification of Functioning, disability, and Health framework. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17(6):400–10.

Crews JE, Campbell VA. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older americans: implications for health and functioning. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):823–9.

Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(3):156–64.

Verbeek E, Drewes YM, Gussekloo J. Visual impairment as a predictor for deterioration in functioning: the Leiden 85-plus study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):397.

Klein R, Lee KE, Gangnon RE, Klein BE. The 25-year incidence of visual impairment in type 1 Diabetes Mellitus the Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(1):63–70.

Varadaraj V, Munoz B, Deal JA, et al. Association of vision impairment with cognitive decline across multiple domains in older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2117416.

Mendez I, Kim M, Lundeen EA, Loustalot F, Fang J, Saaddine J. Cardiovascular Disease risk factors in us adults with vision impairment. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E43.

Rowe F, Brand D, Jackson CA, et al. Visual impairment following Stroke: do Stroke patients require vision assessment? Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):188–93.

Court H, McLean G, Guthrie B, Mercer SW, Smith DJ. Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental comorbidities in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2014;12:181.

Garin N, Olaya B, Lara E, et al. Visual impairment and multimorbidity in a representative sample of the Spanish population. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:815.

Zheng DD, Christ SL, Lam BL, Feaster DJ, McCollister K, Lee DJ. Patterns of chronic conditions and their association with visual impairment and health care use. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(4):387–94.

Hunter DJ, Reddy KS. Noncommunicable Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1336–43.

National Bureau of Statistics. The main data of the seventh national census 2021. http://www.statsgovcn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901080html

Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–8.

Chen H, Mui AC. Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):49–57.

Angus DSZ. Guidelines for constructing consumption aggregates for welfare analysis. Living Standards Measurement Study working paper 135. World Bank 2002, Accessed February 15, 2021.

Pilotto A, Custodero C, Maggi S, Polidori MC, Veronese N, Ferrucci L. A multidimensional approach to frailty in older people. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;60:101047.

Zhou M, Zhao S, Zhao Z. Gender differences in health insurance coverage in China. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):52.

Fu Y, Chen M, Si L. Multimorbidity and catastrophic health expenditure among patients with Diabetes in China: a nationwide population-based study. BMJ Glob Health 2022, 7(2).

Zhao J, Xu X, Ellwein LB, et al. Cataract surgical coverage and visual acuity outcomes in rural China in 2014 and comparisons with the 2006 China nine-province survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;193:62–70.

Zhao X, Lin J, Yu S, et al. Incidence, causes and risk factors of vision loss in rural Southern China: 6-year follow-up of the Yangxi Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107(8):1190–6.

Burton MJ, Ramke J, Marques AP, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(4):e489–e551.

Yan X, Yao B, Chen X, Bo S, Qin X, Yan H. Health insurance enrollment and vision health in rural China: an epidemiological survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):761.

Zhao Y, Atun R, Oldenburg B, et al. Physical multimorbidity, health service use, and catastrophic health expenditure by socioeconomic groups in China: an analysis of population-based panel data. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e840–9.

Kolli A, Seiler K, Kamdar N, et al. Longitudinal associations between vision impairment and the incidence of neuropsychiatric, musculoskeletal, and cardiometabolic chronic Diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;235:163–71.

Sand KM, Wilhelmsen G, Naess H, Midelfart A, Thomassen L, Hoff JM. Vision problems in ischaemic Stroke patients: effects on life quality and disability. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(Suppl 1):1–7.

Tong L, Thumboo J, Tan YK, Wong TY, Albani S. The eye: a window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(9):552–60.

Thorne JE, Woreta FA, Dunn JP, Jabs DA. Risk of cataract development among children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-related uveitis treated with topical corticosteroids. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(4S):21–S26.

Huscher D, Thiele K, Gromnica-Ihle E, et al. Dose-related patterns of glucocorticoid-induced side effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(7):1119–24.

Harithasan D, Mukari SZS, Ishak WS, Shahar S, Yeong WL. The impact of sensory impairment on cognitive performance, quality of life, depression, and loneliness in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(4):358–64.

Guo R, Li X, Sun M, et al. Vision impairment, hearing impairment and functional limitations of subjective cognitive decline: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):230.

Frank CR, Xiang X, Stagg BC, Ehrlich JR. Longitudinal associations of self-reported vision impairment with symptoms of anxiety and depression among older adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(7):793–800.

Valencia WM, Florez H. How to prevent the microvascular Complications of type 2 Diabetes beyond glucose control. BMJ. 2017;356:i6505.

Konstantinidis L, Guex-Crosier Y. Hypertension and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(6):514–21.

Wang S, Bao X. Hyperlipidemia, blood lipid level, and the risk of glaucoma: a meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(4):1028–43.

Barberia-Latasa M, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Alcohol, drinking pattern, and chronic Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14(9).

Wang S, Wang JJ, Wong TY. Alcohol and eye Diseases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(5):512–25.

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network., Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results (2020, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation – IHME) https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

Guiding principles for the. Care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for c: guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians: American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the care of older adults with Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1–E25.

Muth C, van den Akker M, Blom JW, et al. The Ariadne principles: how to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014;12:223.

Park SJ, Ahn S, Woo SJ, Park KH. Extent of exacerbation of chronic health conditions by visual impairment in terms of health-related quality of life. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(11):1267–75.

Floud S, Barnes I, Verfurden M, et al. Disability and participation in breast and bowel cancer screening in England: a large prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(11):1711–4.

Cheng Q, Okoro CA, Mendez I, et al. Health care access and use among adults with and without vision impairment: behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E70.

Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic Diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1407–17.

El-Gasim M, Munoz B, West SK, Scott AW. Associations between self-rated vision score, vision tests, and self-reported visual function in the Salisbury Eye evaluation study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(9):6439–45.

Zimdars ANJ, Gjonça E. The circumstances of older people in England with self-reported visual impairment: a secondary analysis of the English longitudinal study of ageing (ELSA). Br J Visual Impairment. 2012;30:22–30.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) and all workers who collected the data.

Funding

No funding had a role in the study design and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KX and YL designed the study and performed the statistical analysis. KX and YL interpreted data. KX interpreted the findings and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript, edited it for intellectual content, and gave final approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CHARLS was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided written informed consent before participating. The current study is a secondary analysis of the CHARLS public data. This study did not require separate ethical approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, K., Mao, H., Zhang, Q. et al. Associations between vision impairment and multimorbidity among older Chinese adults: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 23, 688 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04393-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04393-0