Abstract

Background

Individuals 65 years or older are presumably more susceptible to becoming frail, which increases their risk of multiple adverse health outcomes. Reversing frailty has received recent attention; however, little is understood about what it means and how to achieve it. Thus, the purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize the evidence regarding the impact of frail-related interventions on older adults living with frailty, identify what interventions resulted in frailty reversal and clarify the concept of reverse frailty.

Methods

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage scoping review approach and conducted searches in CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed, and Web of Science. We hand-searched the reference list of included studies and conducted a grey literature search. Two independent reviewers completed the title, abstract screenings, and full-text review using the eligibility criteria, and independently extracted approximately 10% of the studies. We critically appraised studies using Joanna Briggs critical appraisal checklist/tool, and we used a descriptive and narrative method to synthesize and analyze data.

Results

Of 7499 articles, thirty met the criteria and three studies were identified in the references of included studies. Seventeen studies (56.7%) framed frailty as a reversible condition, with 11 studies (36.7%) selecting it as their primary outcome. Reversing frailty varied from either frail to pre-frail, frail to non-frail, and severe to mild frailty. We identified different types of single and multi-component interventions each targeting various domains of frailty. The physical domain was most frequently targeted (n = 32, 97%). Interventions also varied in their frequencies of delivery, intensities, and durations, and targeted participants from different settings, most commonly from community dwellings (n = 23; 69.7%).

Conclusion

Some studies indicated that it is possible to reverse frailty. However, this depended on how the researchers assessed or measured frailty. The current understanding of reverse frailty is a shift from a frail or severely frail state to at least a pre-frail or mildly frail state. To gain further insight into reversing frailty, we recommend a concept analysis. Furthermore, we recommend more primary studies considering the participant’s lived experiences to guide intervention delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Within the next few decades, the population of people aged 65 and over will continue to rise more than all other age groups, with roughly one in six people over 65 by 2050, compared to one in eleven in 2019 [1]. Individuals over 65 years are presumably at greater risk of becoming frail [2,3,4]. Theoretically, frailty is considered a clinically recognized state of vulnerability that results from an age-related decline in reserve and function, compromising an individual’s ability to cope with the daily challenges of life [5, 6]. The Frailty Phenotype (FP), which is the most dominant conceptual model in literature [3, 7,8,9,10], considers an individual frail by the presence of at least three of five phenotypes: weakness, low levels of physical activity, unintentional weight loss, slow walking speed, and exhaustion. Physical, cognitive, psychological, and social impairments often characterize the different domains of frailty [11]. The physical domain is devoted to FP-related conditions [12], the cognitive domain is the co-existence of physical deficits and mild cognitive impairments [13], the psychological domain focuses on an individual’s coping mechanisms based on their own experiences [14], and the social domain looks at a person’s limited participation in social activities and limitations in social support [15]. Frail older adults are prone to adverse outcomes such as frequent falls, hospitalizations, disabilities, loneliness, cognitive decline, depression, poor quality of life, and even death [16,17,18]. In response, researchers have proposed various interventions to prevent or slow frailty progression by either targeting a single domain (e.g., physical, social, cognitive, etc.) using single component interventions or targeting two or more domains using multi-component interventions.

For example, Hergott and colleagues investigated the effects of a single-component intervention, functional exercise, on acromegaly-induced frailty [19]. Abizanda and colleagues examined the effects of a multi-component intervention, composed of nutrition and physical activity, on frail older people’s physical function and quality of life [20]. Some studies indicate that certain single or multi-component interventions can either reduce frailty, slow its progression, and possibly reverse it [3, 21, 22]. The current understanding of reverse frailty lacks clarity, and the characteristics of interventions related to frailty reversal have not yet been examined in a systematic manner.

Authors have determined the reversal of frailty using various measures. For instance, Kim and colleagues’ study evaluating an intervention composed of exercise and nutritional supplementation in frail elderly community-dwellers demonstrated reversals in FP components [23]. Components included fatigue, low physical activity, and slow walking, an improvement from the presence of 5 components of frailty (according to the FP) to 2, considered a pre-frail state [23]. Conversely, De Souto and colleagues demonstrated frailty reversal based on changes in frailty index (FI) scores, a measure of accumulation of deficits [24]. A FI score of 0.22 or greater indicates frailty, score less than or equal to 0.10 indicates a non-frail state [25,26,27,28,29]. Hergott et al. (2020) used frailty severity to indicate frailty reversal. Participants in their study reversed frailty from a severe state to a mild state [19]. These studies demonstrate the variability in how reversing frailty is measured and understood. For a more comprehensive understanding of reverse frailty and the characteristics of interventions associated with it, a comprehensive review of the literature on this topic is needed. Therefore, through a scoping review, the aim of this study is to provide an overview and synthesis of interventions that have been implemented for frail older adults, to determine whether some interventions have had an impact on reversing frailty.

This methodology is ideal because it encompasses a broad scope and can comprehensively analyze and synthesize data on a subject [30]. Findings from this review will synthesize the evidence regarding the impact of frail-related interventions on older adults living with frailty, identify what interventions resulted in frailty reversal and clarify the concept of reverse frailty.

Guiding conceptual framework

The deficit accumulation model framework, unlike the FP, considers frailty as more than a physical deficit but rather an accumulation of health-related deficits across multiple domains [31]. For this reason, the deficit accumulation model framework serves as our guiding conceptual framework. Through this framework, we recognize frailty as a complex phenomenon, strengthening the case for interventions addressing other health and personal concerns, such as illness, environmental disturbance, social dysfunction, cognitive decline, and psychosocial distress. This framework provides a helpful lens through which we can examine the number of domains addressed in the reported interventions and their relationship to one another.

Methods

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s [30] five-stage approach, elaborated by Levac et al., [32] and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for scoping review [33]. They propose six stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) locating relevant studies, (3) selecting the study, (4) charting data, (5) summarizing results, and (6) consulting with stakeholders. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [34] to guide study reporting. Refer to Additional file 1.

Stage one: identifying the research question

According to Levac and colleagues, fundamental research questions should be broad enough to enable comprehensive analysis and appropriate mapping of relevant literature [32]. Following this, our three research questions are as follows:

-

1.

What is the available literature on the impact of interventions for frail older adults?

-

2.

Did any of these interventions result in frailty reversal?

-

3.

What does it mean to reverse frailty?

Stage two: identifying relevant studies

Using the research questions as a guide, we engaged in an iterative process that involved searching the literature, identifying search terms, developing, and refining search strategies, to identify appropriate studies. We also sought the assistance of an experienced librarian who gave guidance on the use of various electronic databases, provided validation on the appropriateness of the methodology for this study, and conducted a peer-review of the search strategies. An overview of each step is provided below.

Eligibility criteria

JBI’s PCC mnemonic guided eligibility criteria, where P (population): frail older people over 65yrs of age, C (concept): frailty outcome, and C (context): all contexts. We included French and English studies of frail older adults over 65 years because most studies focused on frailty target this age group [35,36,37,38]. All types of interventions for frail older adults were included, except for interventions intended to prevent frailty. We did not apply any limitations to study dates, and settings. All study designs (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods) were considered for inclusion. We excluded conference abstracts, theses, dissertations, and knowledge syntheses, but did refer to their reference list for potential studies. Lastly, we performed a grey literature scan to identify relevant primary studies to ensure a comprehensive literature search.

Search terms

An a priori concept analysis [39] of frailty and frailty interventions revealed relevant search terms regarding the population of interest which included ‘frail elderly, frail, aged hospital patient, institutionalized elderly, very elderly, geriatrics, senior, and aged’. These keywords were presented to and approved by an academic librarian (VL). To capture a comprehensive list of studies that may be relevant, we looked at all types of interventions on frail older adults aimed at either reducing, improving, managing, enhancing, treating, or reversing frailty. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and boolean operators of these terms were used in different databases to identify relevant studies.

Search strategy

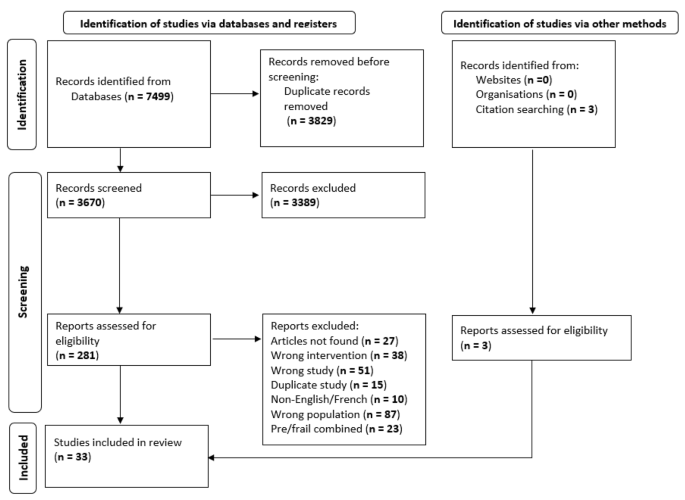

Two academic librarians (VL & VC) guided the development of the search strategy and selected databases. We conducted the searches between August 6th and August 9th, 2021, using MEDLINE (OVID interface), Embase (OVID interface), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Web of Science. We first implemented the search in MEDLINE (Fig. 1), which we later adapted for the other three databases. We manually searched for relevant studies from the reference lists of included/eligible articles and reviewed conference abstracts and secondary analyzes to identify primary studies. A third academic librarian (LS) peer-reviewed the search strategy using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines [40] on August 19th, 2021, without modification. On August 23rd, 2021, we imported the results in RIS format into Covidence, a web-based system for systematic reviews provided by Cochrane [41, 42], which also removed duplicates. We did not import the articles identified via hand-searching the reference list into Covidence for screening. However, two reviewers independently assessed the articles’ eligibility according to our eligibility criteria.

Stage three: study selection

There were two reviewers (AK, OB) involved in this stage, which involved a first and second screening level. The first level included an independent screening of the titles and abstracts, and we decided by selecting ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘maybe’. To qualify for full-text screening, a study must receive two ‘yes’ or two ‘maybe’ votes. Two ‘no’ votes moved the study to exclude, and one ‘no’ vote along with one ‘yes’ or ‘maybe’ vote moved it to conflicts, pending resolution. After consultation with the second reviewer, the first author (AK) and second reviewer (OB) resolved the conflicts together. Following this first-level screen, the second level involved a full-text review of all studies included at the title-abstract level. Using the same principles as the first level screening, the first author (AK) and another reviewer (MA) completed this stage [41, 42]. In cases where full-text articles could not be located or had to be purchased, the corresponding authors were contacted once by email to request copies. We excluded the articles if we did not receive a response after two weeks. We also searched Google Scholar for conference abstracts to see if the full text of the papers had been published and accessible. For most searches, this process was ineffective, leading to the exclusion of all conference abstracts. Articles excluded with reasons can be found in Additional file 2.

Stage Four: charting the data

To extract essential information from the articles, we developed a standard Microsoft Excel form a priori. We used the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist [43] to guide the extraction of the interventions. The form was pilot tested with five articles and revised following recommendations from the research team. After establishing the information to be extracted, we imported the data into Google Forms to facilitate the extracting process for the reviewers. To ensure consistency and reliability in data extraction, two reviewers (AK and MA) independently extracted data from at least 10% of the included studies and compared the results, as recommended by Levac and colleagues [32]. Once we established consistency, the first author (AK) extracted data from the remaining studies.

Data extracted

Data extraction items include a bibliography (authors, the journal-title and year of publication), setting, study population (frail, number and age of participants), aims of the study, the conceptual framework of frailty used, domains of frailty considered, details on interventions that reduce, enhance, treat or reverse frailty, the framework used to develop interventions, assessment tools or instruments to assess frailty outcome before and/or after the intervention, outcomes (frailty completely, partially, or not reversed). Data extraction items can be found in Additional file 3.

Quality appraisal (QA)

We critically appraised included studies strengths and limitations of the studies (e.g., randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, case reports, case series, and cohort studies) using the corresponding JBI checklist for quality appraisal. Checklists, ranged from eight to 13 items [35]. Answers to the questions in each scale ranged from ‘yes’, ‘no’, and ‘unclear’. Three reviewers (YA, MA, and AK) independently appraised the included studies. After completing the assessment, the first author (AK) sorted the answers to determine any discrepancies. When two reviewers reported the same answer, agreement was achieved. When answers differed, the first author extensively reviewed the study and discussed the differences with the other two to reach a consensus. After completion, we converted all the answers into descriptive variables, with yes representing ‘1’ and no and unclear meaning ‘0’. Following recommendations from some studies [44, 45], we used these variables to generate a total score, which we further used to classify a study into “low”, “moderate”, and “high” risk of bias. The quality appraisal interpretation scale can be found in Additional file 4.

Stage five: summarizing and reporting the results

Data analysis

To summarize and elaborate on the first research question, we used a narrative synthesis. Initially, we developed a preliminary synthesis by grouping studies that focused on similar concepts such as but not limited to types of interventions, domains of frailty targeted, outcome of interventions, into a tabular format. Next, using excel, we created bar graphs where we explored relationships between and within studies. Through the use of conceptual mapping, we linked multiple pieces of evidence from individual studies to highlight key concepts and ideas [46, 47].

Our approach to answering the second research question, comparing study demographics and participant characteristics, was descriptive in nature. Using Excel, we calculated the counts and frequencies of variables in each category and compared their percentages across studies [48].

Results

Study selection

We identified 7499 potential records, of which thirty met eligibility criteria. In addition, our hand search of references of included studies revealed three eligible studies, reaching a total of thirty-three. We illustrate the screening and selection process for the included studies using the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews (Fig. 2).

Study characteristics

Sample sizes ranged from one to 250,428 participants across the studies. The most common study designs were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 23) [22,23,24, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], quasi-experimental (n = 4) [69,70,71,72], cohort Studies (n = 3) [20, 73, 74], case series (n = 2) [75, 76] and a case report (n = 1) [19]. Geographically, the studies took place in fifteen different countries, namely Japan (n = 6) [23, 49, 53, 58, 72, 74], Spain (n = 6) [20, 59, 60, 62, 70, 75], United States of America (n = 4) [19, 63, 64, 68], China (n = 3) [51, 52, 69], Sweden (n = 2) [50, 55], South Korea (n = 2) [71, 76], Singapore (n = 2) [22, 54], Australia (n = 1) [66], Netherlands (n = 1) [65], Canada (n = 1) [73], France (n = 1) [24], Brazil (n = 1) [67], Thailand (n = 1) [56], Turkey (n = 1) [57], Denmark (n = 1) [61]. Publication dates ranged from June 23rd, 1994, to January 2nd, 2021, with most articles (n = 24) published after 2015.

Critical appraisal results

The quality assessment scores of the studies ranged from seven to twelve, and study bias was low to moderate for all included studies (Appendix 4). Given that scoping reviews do not mandate the inclusion of studies based on critical appraisal results [77], we did not exclude studies based on their quality assessment cores.

Participant characteristics

Twelve studies (36.4%) included participants over 65 years of age, 11 studies (33.3%) over 70 years of age, and 10 studies (30.3%) over 75 years of age. Most authors referred to participants as male or female without definition making it difficult to distinguish between gender and sex. Consequently, we present the results as reported in the studies. All but one study reported the sex/gender of participants [57], with one study having only male participants [19] and two studies having only female participants as per their eligibility criteria [23, 61]. In many studies, the presence of comorbidities beyond frailty was not a requirement for participation (n = 27). Some studies, however, required comorbid conditions for inclusion, such as acromegaly (n = 1) [19], cardiovascular disease (n = 1) [72], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/lung disease (n = 1) [60], fatigue (n = 1) [69], and risk of mobility disability and sedentary lifestyle (n = 1) [64]. Table 1 presents a summary of participant characteristics.

Most and least common domains targeted

Twenty-six studies involved intervention and control groups. Additionally, each study’s intervention targeted at least one domain of frailty. For example, some interventions targeted one single domain (n = 23) [19, 20, 23, 49, 50, 52, 53, 55,56,57, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 67, 68, 70, 72,73,74], two domains (n = 6) [4, 22, 54, 56, 57, 78], three domains (n = 2) [58, 66], and four domains of frailty (n = 2) [51, 71]. Counts per domain are presented in Fig. 3. The most targeted domains were the physical and the cognitive domains. The social domain was the least targeted.

Single and multi-component interventions

Thirteen studies (39.4%) focused on single-component interventions; twelve were physical activity interventions [52, 53, 56, 60, 62,63,64, 67, 70, 73, 76], and one was a social intervention [74]. These activities were either individually tailored or performed in a group. Over 50% of the studies focused on multicomponent interventions [19, 20, 22,23,24, 49,50,51, 54, 55, 58, 59, 65, 66, 68, 69, 71, 72, 75]. The number of components varied across interventions; from two components to the interventions (n = 10) [20, 23, 49, 50, 55, 59, 65, 68, 69, 75], three components to the interventions (n = 8) [19, 22, 24, 54, 58, 66, 71, 72], or four components to the interventions (n = 2) [51, 71]. Characteristics of the interventions are.

included in Table 2.

Most and least common frailty definitions used

Frailty was defined in all but three studies (n = 30) [49, 61, 68]. Two different definitions of frailty were used dominantly: Fried’s phenotype (n = 20) [20, 22, 23, 51,52,53,54, 56, 57, 59, 62, 64, 66, 67, 69,70,71,72, 75, 76], and the Frailty Index (n = 4) [24, 60, 71, 73]. Notwithstanding, other definitions of frailty involved the use of the clinical frailty scale [19] and checklist such as the kihon checklist [74].

Studies without frailty reversal outcome

In the 33 studies included, the results of 22 did not indicate reversal of frailty. Among these, 36.36% (n = 8) focused solely on physical interventions [53, 57, 60,61,62,63,64, 76], while 63.63% (n = 14) combined physical activity with nutritional, cognitive, social, pharmaceutical, or behavioral interventions [20, 24, 49,50,51, 54, 55, 58, 65, 66, 68, 69, 71, 75]. Although physical activity remains a significant factor in these studies, the types of physical activity (aerobic, strengthening, gait, resistance, etc.) varied. Research suggests that resistance exercise performed at high intensity over a minimum of 12 weeks has the most beneficial effect on physical frailty [68, 79]. When done regularly over the course of six months, it has the potential to improve both the physical and physiological aspects of frailty [80]. In this context, we noted that resistance exercise was more prevalent than other forms of physical activity. Although similar physical activities were often implemented, their characteristics often differed. For example, there was variation in frequency from daily to three times per week, variation in intensity from moderate to high, and variation in duration from 6 weeks to 6 months.

In addition to physical activity, other types of interventions were also used, including cognitive interventions such as memory and reasoning training, pharmaceutical interventions such as medication reconciliation, social interventions such as improving social lifestyles, and behavioral interventions such as goal setting, action plans, and goal execution. Similarly, the characteristics of these interventions were heterogeneous across studies, with some provided as group therapies, and others designed as per the needs of participants.

Studies indicating frailty reversal outcome

Eleven studies reported frailty reversal as an outcome [19, 22, 52, 56, 59, 67, 70, 72,73,74, 81]. The physical domain was targeted in over 80% of the studies (n = 9) [19, 23, 52, 56, 59, 67, 70, 72, 73], while the social [74] and cognitive domains [22] were each targeted in one study. In single-component interventions such as physical activities (n = 5) [52, 56, 67, 70, 73], resistance exercises appeared to be the most common, done on its own or in combination with other physical exercises. Meanwhile, the social intervention enhanced the patient’s social capital, a social network that facilitates access to benefits and helps individuals solve problems through association [74].

The multi-component intervention consisted of physical activity combined with either nutritional counselling/advice or supplements. Some (n = 5) of the interventions included physical activity, nutrition, plus pharmaceutical intervention in one study [72], physical activity, nutritional plus cognitive intervention in another study [22], and physical activity combined with occupational and speech therapy [19], with intervention characteristics varying across studies.

Definition/clarity about the concept of reverse frailty

Authors of 17 studies referred to frailty as a reversible condition. However, the concept of reversing frailty was not defined or explained in six studies [22, 54, 57, 58, 63, 64]. When defined, definitions varied. Some authors defined it as a shift from a frail to pre-frail state (n = 1) [56], frail to non-frail (n = 2) [24, 59], frail to pre- and non-frail (7) [23, 52, 67, 70, 72,73,74], and severe frailty to mild frailty (n = 1) [19]. What was common across all definitions is that the direction of reversal was from a more severe state of frailty to a less severe state of frailty or pre-frail state. What is different is the degree of frailty, given that some definitions indicated a participant should be frail while others indicated participants being severely frail. This suggests the use of different definitions, criteria, methods, and measures to determine whether frailty reversal occurred. For example, seven of the studies that showed reversal used the definition of Fried et al., [23, 52, 56, 59, 67, 70, 72], one study used the frailty index [73], and another study used the clinical frailty scale [19]. Finally, one study used the Kihon checklist, consisting of 25 yes or no questions on daily-life-related activities, motor functions, nutritional status, oral functions, homebound, cognitive functions, and depressed mood [74].

Discussion

Our study aimed to summarize and synthesize evidence on the impact of interventions on frail older adults, to identify those that resulted in frailty reversal and those that did not. In cases where frailty reversal was indicated, we explored the meaning of the concept of reversing frailty. Among the 33 studies included, frailty was revealed to be a complex syndrome encompassing multiple domains, indicating the need for interventions targeting different aspects. Even though some interventions were more prevalent, we observed similarities between types of interventions across studies that showed frailty reversal and those that did not. We noted that the physical domain received the most attention across all studies, whereas the social domain received the least attention in studies with frailty reversal outcomes. Considering that frailty has been defined, addressed, or assessed in multiple ways throughout the studies, further exploration will contribute to clarifying the concept of reversing frailty. These findings lead us to the following points.

Frailty reversal may depend on targeted domains

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to systematically map interventions that indicate frailty reversal as an outcome and relates these interventions to the targeted frailty domains. Using the deficit accumulation model framework as our conceptual framework, we anticipated interventions would target multiple domains of frailty to achieve frailty reversal. However, this was not the case. We identified that the physical domain of frailty is the most frequently targeted as compared to the cognitive, social, and psychological domains. This is supported by the findings of other reviews where authors perceived frailty as primarily a physical impairment, measured by the Fried criteria [82,83,84,85,86,87]. This finding suggests that reversing frailty may probably depend on the domain that is targeted by the intervention, or the conceptual framework used to identify and measure its outcome.

Definition of reverse frailty remains unclear

There is no standard definition of reverse frailty, yet the concept appears in several research studies. We used a descriptive approach such as percentages to examine the differences and similarities between the various definitions. A fundamental similarity is that the individual must be deemed frail at baseline. However, the process of determining an individual’s frailty score or status differed among the studies because of the different assessment instruments used. Another similarity was that to reverse frailty, frailty scores or status must not progress to a more severe state but rather improve to a pre-frail or milder state of frailty. Further research is required to clarify this concept, preferably through concept analysis.

Absence of a universal method to reverse frailty

This review included a heterogeneous group of studies with a diverse range of participant characteristics, intervention types, and duration of intervention. Single-component and multi-component interventions have shown efficacy in reversing frailty, with more studies of single-component interventions (i.e., physical activity or social interventions) than the latter.

Use of single-component interventions to reverse frailty

Our study identified physical activity as the most used intervention across studies that reversed frailty. This fits with previous findings that physical activity is essential in interventions for frail older adults [85,86,87,88]. The activities were performed together (combination exercises) or separately (resistance only). In one study, frailty was reversed as early as six weeks [70]. The authors attributed this to the combination of resistance, strength training and aerobic exercises. Therefore, when combined with other types of exercise, resistance exercise could promote the rapid improvement of physical frailty.

According to a recent scoping review, social frailty has not received adequate attention [15]. Based on the findings of our review, we agree with this notion, given we identified only one study [74] that explored frailty reversal through singular intervention. Using an established checklist of items, the study monitored the effects of enhanced social capital (including interaction with neighbours, trust in the community, social participation in activities) on frailty reversal over two years. The results showed that 31.8% of the participants’ frailty statuses reversed to pre-frail or non-frail Another study [58] showed that increasing participants’ social capital improved their adherence to activities and encouraged them to continue interventions even after the study had ended. Thus, interventions that consider this approach may have better outcomes when it comes to frailty reversal.

Use of multi-component interventions to reverse frailty

The studies(n = 11) that showed frailty reversal as an outcome employed a combination of two or more intervention components tailored to participant needs or conducted in small groups. Physical activity, particularly resistance exercise, is recommended in conjunction with nutritional interventions as a preventative measure of muscle atrophy in older adults [58], which may explain why this combination was the most common among the multi-component interventions. We also noted other physical activities such as strength, balance gait and aerobic exercise performed in combination with resistance exercise at varying frequencies and durations. Nutritional interventions included dietary supplements and nutritional education (advice and counselling) on healthy food choices, with the latter being the most reportedly used. We related the advantage of this approach as reported in other studies where Interventions that aimed to empower participants by way of soliciting and incorporating their input (e.g., choosing meals) were more likely to result in participants feeling in control and autonomous over their dietary choices [89, 90]. This may explain how nutritional education may provide older adults with more food variety and improved food intake compared with dietary supplements [58]. In addition to nutritional education and physical activity, Ushijima et al. [72] also provided medication guidance, to mitigate the effects of polypharmacy, which have been shown to negate the effects of physical and nutritional interventions [91, 92].

Recommendations

The results and discussion points above guide our research, practice, and policy recommendations.

Research

In this scoping review, the reporting of the interventions was suboptimal. For example, not all studies reported whether interventions were modified, personalization of interventions were planned, fidelity and adherence were measured, or how intervention fidelity was maintained or improved. Therefore, we recommend that authors use the template for intervention description and replication (TIDIER) checklist [43] or the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) [93] whenever possible to improve intervention reporting. These checklists facilitate clinician use of interventions and researchers’ synthesis and replication. Additionally, we recommend that authors of future studies provide details on the definition and components of frailty. Clinically, this may help identify groups of individuals in need of care and facilitate understanding among researchers.

Despite having no study design restrictions, we did not identify any qualitative or mixed method studies about frailty reversal interventions. None of the included studies reported engaging participants in decision-making or incorporating participant experiences into intervention delivery. A recent scoping review [94] echoes this concern, as older adults worry that they are not involved in health and well-being decisions. It is known that engaging older adults in decision-making improves health outcomes [95]. Therefore, we recommend qualitative and mixed methods studies aiming to integrate the older adults’ perspective regarding intervention development, evaluation, or implementation.

Acknowledging that frailty is complex in nature, RCTs with a large sample size could be beneficial to investigate the social, psychological, and cognitive aspects of frailty, which have received little attention to date.

Among the studies that did not report frailty reversal as an outcome, behavioural enhancement was one of the interventions implemented. The use of behavioral enhancement has been associated with the development of self-management skills and the maintenance of long-term changes [69]. It is therefore our recommendation that more studies consider a behavioural enhancement approach to facilitate adherence to interventions and maintain the benefits of interventions over the long-term. Lastly, given that frailty assessments and measurements are inconsistent, there is a need for more work to standardize them.

Practice

Further to considering the perspectives of older adults with frailty, we recommend tailoring interventions to fit the needs and capabilities of individuals rather than generalizing it across an entire population. For example, Latham and colleagues [96] conducted a resistance training program with Vitamin D supplements over ten weeks for participants with certain functional limitations, such as dependence on others for activities of daily living, prolonged bed rest, or impaired mobility. Contrary to other studies reporting positive effects of resistance exercise, such as improved functional outcomes and decreased frailty scores during this period [53, 58, 67, 68], Latham and colleagues reported increased fatigue and musculoskeletal injury risks, which may be related to the participants’ functional limitations. We, therefore, recommend tailoring interventions to match participants’ needs and abilities rather than having set durations, frequencies, or intensities of interventions. Another reason is that some older adults may have functional limitations affecting their ability to adhere to prescribed interventions, including the potential adverse effects of polypharmacy on intervention effectiveness [92].

Policy

Research results influence guidelines and expectations for delivering care, services, and programs [97]. Frailty is becoming a potential public and global health concern, as indicated by the inclusion of studies from North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, etc. This reinforces the need to prevent or reverse this geriatric syndrome. Future studies should investigate frailty in all continents to increase our understanding on the global challenges of expectations, implementation, or care delivery for frail older adults. Such information can facilitate the transfer of healthcare professionals between continents by bridging the knowledge gap concerning frailty, its interventions, and potential strategies for reversing the condition.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has strengths and limitations. We established a reproducible, systematic approach, from the literature search to screening and data extraction. Furthermore, the search strategy was guided and peer-reviewed by academic librarians with extensive knowledge of scoping and systematic reviews. We quality appraised included articles permitting us to have a better sense of the quality of the evidence on this topic. Although not formally published or registered, an a priori protocol approved by the research team guided this study. In comparison to the protocol, a few changes have been made to this study, such as not obtaining expert consultation and revising the research questions.

In terms of limitations, included studies were heterogeneous in their study objectives, frailty definition, frailty domain targeted, and intervention characteristics. Some studies used self-administered questionnaires as outcome measures to assess frailty, potentially increasing the risk of bias and making replication difficult because there is no guarantee of having the same responses among different participants. In addition, two studies did not report the characteristics of the intervention [19, 73], and one indicated that participants were frail but did not specify how frailty was determined [68]. Lastly, we acknowledge that using only a few databases may have limited the number of studies we were able to find.

Conclusions

We used a narrative and descriptive approach to synthesize the included studies. Despite the lack of a standard definition of frailty, we observed similar interventions across studies that reported an outcome of frailty reversal and those that did not. When frailty reversal was indicated, we explored the meaning of the concept. We noted that the physical domain received the most attention across all studies. In contrast, the social domain received the least attention in studies with frailty reversal outcomes.

This study confirms that frailty is a complex and worrying geriatric syndrome. As the world’s population ages, frailty is becoming a serious issue for public and global health. Thus, it is crucial for frailty to be considered a holistic phenomenon with a multi-factor approach rather than merely a physical condition. This requires more research addressing multiple domains to target its prevention and reversal. Our findings indicate that reversing frailty requires that a person first be considered frail, regardless of how frailty is assessed. Although we discovered different ways of assessing frailty among the studies, a key highlight is the fact that the ability to reverse frailty may depend on how frailty is defined and measured. Hence, a consensus on what reverse frailty means is necessary. A promising but challenging area for future research could be qualitative analysis that explores frail older adults’ lived experiences and perspectives. This will guide the development and implementation of possible interventions to reverse this critical geriatric syndrome.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Dur:

-

Duration

- FI:

-

Frailty Index

- FP:

-

Frailty Phenotype

- Freq:

-

Frequency

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- HI:

-

High intensity

- iADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- KCL:

-

Kihon checklist

- MEP:

-

Multi-component Exercise Program

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- PIFU:

-

Post-intervention follow-up

- PRESS:

-

Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes

- RAI-HC:

-

Resident Assessment Instrument-Home Care

- RCTs:

-

Randomized control trials

- RMR:

-

Resting metabolic rate

- RT:

-

Resistance training

- SPPB:

-

Short Physical Performance Battery

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

- StaRI:

-

Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies

- wks:

-

Weeks

- yrs:

-

years

- m:

-

months

References

United Nations. World Population Ageing 2019. 2019.

Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Gafni A. Nurse-led health promotion interventions improve quality of life in frail older home care clients: Lessons learned from three randomized trials in Ontario, Canada. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19:118–31.

Kojima G, Liljas AEM, Iliffe S. Frailty syndrome: implications and challenges for health care policy. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:23–30.

Sacha M, Sacha J, Wieczorowska-Tobis K. Multidimensional and physical Frailty in Elderly People: participation in Senior Organizations does not prevent Social Frailty and most prevalent psychological deficits. Front Public Heal. 2020;8:1–7.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394:1365–75.

Kamaruzzaman SB. Frailty in older people. Geriatric medicine. Springer, Singapore, 2018, 27–41.

Bahat G, Ilhan B, Tufan A et al. Success of simpler modified Fried Frailty Scale to predict mortality among nursing home residents. J Nutr Heal Aging 2021; 1–5.

McIsaac DI, Macdonald DB, Aucoin SD. Frailty for Perioperative Clinicians: a narrative review. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1450–60.

Vella Azzopardi R, Beyer I, Vermeiren S, et al. Increasing use of cognitive measures in the operational definition of frailty—A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;43:10–6.

Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:3–10.

Van Oostrom SH, Van Der ADL, Rietman ML, et al. A four-domain approach of frailty explored in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1–12.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:146–57.

Kwan RYC, Leung AYM, Yee A, et al. Cognitive Frailty and its Association with Nutrition and Depression in Community-Dwelling Older People. J Nutr Heal Aging. 2019;23:943–8.

Hoeyberghs LJ, Schols JMGA, Verté D, et al. Psychological Frailty and Quality of Life of Community Dwelling Older People: a qualitative study. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15:1395–412.

Bunt S, Steverink N, Olthof J, et al. Social frailty in older adults: a scoping review. Eur J Ageing. 2017;14:323–34.

Clegg. Frailty in Older People. Lancet. 2014;381:752–62.

Hao Q, Zhou L, Dong B, et al. The role of frailty in predicting mortality and readmission in older adults in acute care wards: a prospective study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–8.

Langlois F, Vu TTM, Chassé K, et al. Benefits of physical Exercise training on Cognition and Quality of Life in Frail older adults. Journals Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68:400–4.

Hergott CG, Lovins J. The impact of functional exercise on the reversal of acromegaly induced frailty: a case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1768456. Epub ahead of print.

Abizanda P, López MD, García VP, et al. Effects of an oral Nutritional Supplementation Plus Physical Exercise intervention on the physical function, Nutritional Status, and quality of life in Frail Institutionalized older adults: the ACTIVNES Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:439e9–16.

Marcucci M, Damanti S, Germini F, et al. Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: a journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Med. 2019;17:1–11.

Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, et al. Nutritional, Physical, Cognitive, and combination interventions and frailty reversal among older adults: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Med. 2015;128:1225–1236e1.

Kim H, Kim M, Kojima N, et al. Effects of exercise and nutritional supplementation in community-dwelling frail elderly women in Japan: a randomized placebo controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:107.

de Souto Barreto P, Rolland Y, Maltais M, et al. Associations of Multidomain Lifestyle intervention with Frailty: secondary analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Med. 2018;131:NPAG–NPAG.

Kulminski A, Yashin A, Arbeev K, et al. Cumulative index of health disorders as an indicator of aging-associated processes in the elderly: results from analyses of the National Long Term Care Survey. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:250–8.

Hoover M, Rotermann M, Sanmartin C, et al. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Heal Rep. 2013;24:10–7.

Martínez-Velilla N, Herce PA, Herrero ÁC, et al. Heterogeneity of different tools for detecting the prevalence of Frailty in nursing Homes: feasibility and meaning of different approaches. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:898. .e1-898.e8.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:722–7.

Theou O, Tan ECK, Bell JS, et al. Frailty levels in residential aged care Facilities measured using the Frailty Index and FRAIL-NH Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:e207–12.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8:19–32.

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323–36.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

Joanna Briggs Institute. The scoping review framework.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Apóstolo J, Cooke R, Bobrowicz-Campos E, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent pre-frailty and frailty progression in older adults: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports. 2018;16:140–232.

Chu W, Chang S, Ho H, et al. The relationship between Depression and Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older People: a systematic review and Meta‐analysis of 84,351 older adults. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019;51:547–59.

García-García FJ, Carcaillon L, Fernandez-Tresguerres J, et al. A new operational definition of Frailty: the Frailty Trait Scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:371. .e7-371.e13.

Taube E, Kristensson J, Midlöv P, et al. The use of case management for community-dwelling older people: the effects on loneliness, symptoms of depression and life satisfaction in a randomised controlled trial. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32:889–901.

Ankilma do Nascimento Andrade, Maria das Graças Melo Fernandes MML da N. FRAILTY IN THE ELDERLY: CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS. 2012; 21: 748–56.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Kellermeyer L, Harnke B, Knight S. Covidence and Rayyan. J Med Libr Association: JMLA. 2018;106:580–3.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. www.covidence.org; 2021.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:1–12.

Foe-Essomba JR, Kenmoe S, Tchatchouang S, et al. Diabetes mellitus and tuberculosis, a systematic review and meta-analysis with sensitivity analysis for studies comparable for confounders. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0261246.

Adalbert JR, Varshney K, Tobin R, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients co-infected with COVID-19 and Staphylococcus aureus: a scoping review. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:985.

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5:101–17.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A et al. Narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. ESRC Methods Program 2006; 93.

Nassaji H. Qualitative and descriptive research: data type versus data analysis. Lang Teach Res. 2015;19:129–32.

Imaoka M, Higuchi Y, Todo E, et al. Low-frequency Exercise and vitamin D supplementation reduce Falls among Institutionalized Frail Elderly. Int J Gerontol. 2016;10:202–6.

Lammes E, Rydwik E, Akner G. Effects of nutritional intervention and physical training on energy intake, resting metabolic rate and body composition in frail elderly. A randomised, controlled pilot study. J Nutr Heal AGING. 2012;16:162–7.

Li C-M, Chen C-Y, Li C-Y, et al. The effectiveness of a comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention program for frailty in community-dwelling older people: a randomized, controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(Suppl 1):39–42.

Liao YY, Chen IH, Wang RY. Effects of Kinect-based exergaming on frailty status and physical performance in prefrail and frail elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep; 9. Epub ahead of print 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45767-y.

Nagai K, Miyamato T, Okamae A, et al. Physical activity combined with resistance training reduces symptoms of frailty in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;76:41–7.

Ng T-P, Chan G, Nyunt M, et al. Multi-domains lifestyle interventions reduces depressive symptoms among frail and pre-frail older persons: Randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:918–26.

Rydwik E, Frändin K, Akner G. Effects of a physical training and nutritional intervention program in frail elderly people regarding habitual physical activity level and activities of daily living—A randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:283–9.

Sadjapong U, Yodkeeree S, Sungkarat S, et al. Multicomponent Exercise Program reduces Frailty and inflammatory biomarkers and improves physical performance in Community-Dwelling older adults: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113760. Epub ahead of print.

Sahin UK, Kirdi N, Bozoglu E, et al. Effect of low-intensity versus high-intensity resistance training on the functioning of the institutionalized frail elderly. Int J Rehabil Res. 2018;41:211–7.

Seino S, Nishi M, Murayama H, et al. Effects of a multifactorial intervention comprising resistance exercise, nutritional and psychosocial programs on frailty and functional health in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, controlled, cross-over trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2034–45.

Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ, Gómez-Cabrera MC, Pérez-Ros P, et al. A Multicomponent Exercise intervention that reverses Frailty and improves cognition, emotion, and Social networking in the Community-Dwelling Frail Elderly: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:426–33.

Torres-Sanchez I, Valenza MC, Cabrera-Martos I, et al. Effects of an Exercise intervention in Frail older patients with chronic obstructive Pulmonary Disease hospitalized due to an exacerbation: a Randomized Controlled Trial. COPD-JOURNAL CHRONIC Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;14:37–42.

Vestergaard S, Kronborg C, Puggaard L. Home-based video exercise intervention for community-dwelling frail older women: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:479–86.

Arrieta H, Rezola-Pardo C, Gil SM, et al. Effects of Multicomponent Exercise on Frailty in Long‐Term nursing Homes: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1145–51.

Brown M, DR S. Low-intensity exercise as a modifier of physical frailty in older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:960–5.

Cesari M, Vellas B, Hsu F-C, et al. A physical activity intervention to treat the frailty syndrome in older persons-results from the LIFE-P study. Journals Gerontol Ser a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70:216–22.

Chin A, Paw MJM, De Jong N, Schouten EG, et al. Physical exercise and/or enriched foods for functional improvement in frail, independently living elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:811–7.

Cameron ID, Fairhall N, Langron C, et al. A multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:65.

Coelho-Júnior HJ, Uchida MC. Effects of Low-Speed and High-Speed Resistance Training Programs on Frailty Status, physical performance, cognitive function, and blood pressure in Prefrail and Frail older adults. Front Med. 2021;8:1–19.

Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND, et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1769–75.

Liu JY-W, Lai CKY, Siu PM, et al. An individualized exercise programme with and without behavioural change enhancement strategies for managing fatigue among frail older people: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:521–31.

Losa-Reyna J, Baltasar-Fernandez I, Alcazar J, et al. Effect of a short multicomponent exercise intervention focused on muscle power in frail and pre frail elderly: a pilot trial. Exp Gerontol. 2019;115:114–21.

Oh G, Jang I-Y, Lee H, et al. Long-term effect of a Multicomponent intervention on physical performance and Frailty in older adults. Innov Aging. 2019;3:919–S920.

Ushijima A, Morita N, Hama T, et al. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation on physical function and exercise capacity in elderly cardiovascular patients with frailty. J Cardiol. 2021;77:424–31.

Larsen RT, Turcotte LA, Westendorp R, et al. Frailty Index Status of Canadian Home Care clients improves with Exercise Therapy and declines in the Presence of Polypharmacy. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:766.

Takatori K, Matsumoto D. Social factors associated with reversing frailty progression in community-dwelling late-stage elderly people: An observational study. PLoS One; 16. Epub ahead of print 2021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247296.

Cadore EL, Moneo ABB, Mensat MM, et al. Positive effects of resistance training in frail elderly patients with dementia after long-term physical restraint. Age (Omaha). 2014;36:801–11.

Kim YJ, Park H, Park JH, et al. Effects of Multicomponent Exercise on cognitive function in Elderly korean individuals. J Clin Neurol. 2020;16:612–23.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143.

Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polańska B, Wleklik M, et al. Frailty Syndrome: nursing interventions. SAGE Open Nurs. 2018;4:1–11.

Marcos-Pardo PJ, Orquin-Castrillón FJ, Gea-García GM, et al. Effects of a moderate-to-high intensity resistance circuit training on fat mass, functional capacity, muscular strength, and quality of life in elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7830.

Saragih ID, Saragih IS, Batubara SO et al. Effects of resistance bands exercise for frail older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Clin Nurs. Epub ahead of print 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15950.

Kim H, Suzuki T, Kim M, et al. Effects of exercise and milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) supplementation on body composition, physical function, and hematological parameters in community-dwelling frail japanese women: a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled, follow-up trial. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–20.

Campbell E, Petermann-Rocha F, Welsh P et al. The effect of exercise on quality of life and activities of daily life in frail older adults: A systematic review of randomised control trials. Exp Gerontol; 147. Epub ahead of print 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111287.

Stookey AD, Katzel LI. Home Exercise Interventions in Frail older adults. Curr Geriatr REPORTS. 2020;9:163–75.

Kelaiditi E, van Kan GA, Cesari M. Frailty: role of nutrition and exercise. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:32–9.

Labra C, De, Guimaraes-pinheiro C, Maseda A et al. Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. Epub ahead of print 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0155-4.

Arantes PMM, Alencar MA, Pereira LSM. Physical therapy treatment on frailty syndrome: systematic review. 2009; 13: 365–75.

Chin A, Paw MJM, Uffelen JGZ, Van, Riphagen I et al. The functional Effects of Physical Exercise Training in Frail a systematic review. 2008; 38: 781–93.

Dedeyne L, Deschodt M, Verschueren S, et al. Effects of multi-domain interventions in (pre)frail elderly on frailty, functional, and cognitive status: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:873–96.

Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci; 13. Epub ahead of print 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z.

Krist AH, Tong ST, Aycock RA, et al. Engaging patients in decision-making and Behavior Change to Promote Prevention. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240:284–302.

Dagli RJ, Sharma A. Polypharmacy: a global risk factor for elderly people. J Int oral Heal JIOH. 2014;6:i–ii.

Katsimpris A, Linseisen J, Meisinger C, et al. The Association between Polypharmacy and physical function in older adults: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1865–73.

Duncan E, O’Cathain A, Rousseau N, et al. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–12.

Durepos P, Sakamoto M, Alsbury K et al. Older adults’ perceptions of Frailty Language: a scoping review. Can J Aging. Epub ahead of print 2021. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980821000180.

Elliott J, McNeil H, Ashbourne J, et al. Engaging older adults in Health Care Decision-Making: a Realist synthesis. Patient. 2016;9:383–93.

Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the frailty interventions trial in elderly subjects (FITNESS). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:291–9.

Erismann S, Pesantes MA, Beran D, et al. How to bring research evidence into policy? Synthesizing strategies of five research projects in low-and middle-income countries. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2021;19:1–13.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Ottawa Health Science Librarians: Valentina Ly (VL), Victoria Cole (VC), and Lindsey Sikora (LS), for their guidance in ensuring searching for relevant studies. Special thanks also go to Ojongetakah Enokenwa Baa and Mbi Ayuk Solange, who acted as secondary screeners for selecting relevant studies.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK, the principal investigator, initiated the project, designed the search strategy, carried out data extracted, and performed an analysis of the findings. KL critiqued and guided the project’s direction, such as the research questions, methodology, and results. ML offered suggestions about the thesis design results, critiqued and provided feedback as needed. CB guided the development of the research topic, provided regular feedback, and edited and approved every stage of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolle, A.T., Lewis, K.B., Lalonde, M. et al. Reversing frailty in older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 23, 751 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04309-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04309-y