Abstract

Background

In the early COVID-19 pandemic concerns about the correct choice of analgesics in patients with COVID-19 were raised. Little data was available on potential usefulness or harmfulness of prescription free analgesics, such as paracetamol. This international multicentre study addresses that lack of evidence regarding the usefulness or potential harm of paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission in a setting of COVID-19 disease within a large, prospectively enrolled cohort of critically ill and frail intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

Methods

This prospective international observation study (The COVIP study) recruited ICU patients ≥ 70 years admitted with COVID-19. Data on Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, prior paracetamol intake within 10 days before admission, ICU therapy, limitations of care and survival during the ICU stay, at 30 days, and 3 months. Paracetamol intake was analysed for associations with ICU-, 30-day- and 3-month-mortality using Kaplan Meier analysis. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were used to stratify 30-day-mortality in subgroups for patient-specific characteristics using logistic regression.

Results

44% of the 2,646 patients with data recorded regarding paracetamol intake within 10 days prior to ICU admission took paracetamol. There was no difference in age between patients with and without paracetamol intake. Patients taking paracetamol suffered from more co-morbidities, namely diabetes mellitus (43% versus 34%, p < 0.001), arterial hypertension (70% versus 65%, p = 0.006) and had a higher score on Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS; IQR 2–5 versus IQR 2–4, p < 0.001). Patients under prior paracetamol treatment were less often subjected to intubation and vasopressor use, compared to patients without paracetamol intake (65 versus 71%, p < 0.001; 63 versus 69%, p = 0.007). Paracetamol intake was not associated with ICU-, 30-day- and 3-month-mortality, remaining true after multivariate adjusted analysis.

Conclusion

Paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission was not associated with short-term and 3-month mortality in old, critically ill intensive care patients suffering from COVID-19.

Trial registration.

This prospective international multicentre study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier “NCT04321265” on March 25, 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Older patients are more likely to die from COVID-19, the disease caused by Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. Early studies of COVID-19 have shown that especially old and frail patients are at particular risk for a worse outcome compared to younger people, with case fatality rates increasing up to 14.8% in patients aged 80 years and more. The majority of COVID-19 related deaths are in patients aged 80 years or greater [1,2,3,4,5]. These observations are in line with past studies of outcome of frail intensive care unit (ICU) patients showing that frailty – and not old age alone—is an important predictor of outcome in critically ill patients [6, 7]. In response to the eminently high vulnerability of old and frail patients, many countries chose to prioritize this vulnerable group in their vaccination programs to protect them from a likely fatal outcome [8]. This patient cohort is also of particular interest since they frequently take inter-current medications and have comorbid conditions.

In the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic there were warnings not to use prescription-free analgesics such as ibuprofen and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), since they were suspected to cause higher morbidity and mortality. Those statements were taken up by the media and led to widespread confusion and fear of – up to then – commonly used drugs for everyday ailments, like headaches and fever [9, 10].

Several studies suggested a potential influence of NSAIDs on the clinical course of respiratory viral diseases, namely worsening the overall outcome due to a suppression of the initial inflammatory cascade [11, 12]. Despite an early focus on a potential detrimental effect of NSAIDs on clinical outcomes, studies have shown no association of NSAID use with mortality [12, 13]. However, the role and influence of paracetamol, often used as an alternative to NSAIDs, remains unclear. To date, no data are available on the effects of paracetamol intake on COVID-19 disease in the vulnerable cohort of very old and critically ill patients admitted to ICUs.

This international multicentre study addresses this lack of evidence regarding the usefulness or potential harm of paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission in a setting of COVID-19 disease within a large, prospectively enrolled cohort of critically ill and frail ICU patients.

Methods

Design and settings

This international multicentre study is part of the Very old Intensive care Patients (VIP) project and has been endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM, http://www.vipstudy.org). Furthermore, it was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT04321265) and planned in adherence to the European Union General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) directive, which is implemented in most participating countries. The COVIP (COVID-19 in very old intensive care patients) investigation aims to improve and enhance the knowledge about relevant factors for predicting mortality in older COVID-19 patients to help detect these patients early on and prevent a worse outcome. National coordinators were responsible for ICU recruitment, coordination of national and local ethical permissions and supervision of patient recruitment, as in the previous VIP studies [14, 15]. Ethical approval was mandatory for study participation. In most of the countries informed consent was obligatory for inclusion. However, due to a waiver of informed consent by some local Ethics committees, in a few countries, recruitment was possible without informed consent as previously described [16]. Overall, 138 intensive care units from 28 countries participated in the COVIP study [5, 17]. A list of all collaborating centers is given in the acknowledgement section.

Study population

COVIP recruited patients with proven COVID-19, defined as a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result, aged 70 years or older who were admitted to an ICU. Data collection started at ICU admission. Thus, data about pre-ICU triage were not available. The admission day was defined as day one, and all consecutive days were numbered sequentially from the admission date. The dataset contained patients enlisted to the COVIP study from 19th March 2020 until the 4th of February 2021.

Data collection

All study sites used a uniform online electronic case report form (eCRF). For this subgroup analysis, only patients with documented information regarding intake of paracetamol up to ten days prior to ICU admission were included.

Paracetamol intake

Paracetamol intake was defined as any oral or intravenous intake regardless of dosage and duration within the ten days prior to ICU admission, including during prior hospitalization, as reported by patient interviews; in case the patient was not able to respond, the relatives were asked to provide information. No differentiation was made between regular or irregular, i.e., single use, in reporting paracetamol intake.

The Sequential Organ Failure Score (SOFA) on admission was recorded [14, 15]. For calculation of the Horowitz Index (paO2/FiO2-ratio), the first arterial blood gas analysis after ICU admission was used ideally within one hour of ICU admission. Additionally, the need for non-invasive (NIV) or invasive ventilation, prone positioning, tracheostomy, vasopressor use, renal replacement therapy (RRT) and limitation or withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy during the ICU stay were recorded.

Data storage

The eCRF was constructed with the REDCap software [18]. Data storage and hosting of the eCRF took place on a secure server of Aarhus University in Denmark. The servers were operated in collaboration between the Information Technology Department and the Department of Clinical Medicine of the Aarhus University.

Frailty assessment

The frailty level prior to the acute illness and hospital admission was assessed using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) as described previously [14, 15]. Patients were grouped into three categories: fit (CFS 0–3) vulnerable (CFS 4) and frail (CFS ≥ 5).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were described as median ± interquartile range (IQR). Differences between independent groups were calculated using the Mann Whitney U-test. Categorical data were expressed as percentages. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used for assessment of mortality. For calculating differences between groups, the chi-square test was applied. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess associations of paracetamol use with ICU-, 30-days and 3-months-mortality. We report (adjusted) odds ratios (OR) with respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). We performed sensitivity analyses plotting univariate OR and 95%CI. All tests were two-sided. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stata 16 was used for all statistical analyses (StataCorp LLC, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Brownsville, Texas, USA).

Results

Demographic data (age, sex, frailty, co-morbidities)

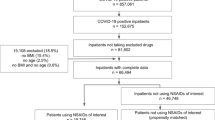

The study included 2,646 patients in total, of which 1,480 patients (56%) did not take paracetamol up to ten days prior to admission to an intensive care unit, whereas 1,166 patients (44%) confirmed paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission. The median age was 75 years in both groups (IQR 72–79 years, p > 0.98); significantly more women reported an intake of paracetamol 10 days prior to ICU admission. Patients on paracetamol intake were slightly more frail in comparison to patients without paracetamol intake (IQR 2–5 versus 2–4, p < 0.001). In addition, patients using paracetamol had more co-morbidities, such as arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus in comparison to non-users (43% versus 34%, p < 0.001 for diabetes mellitus and 70% vs 65%, p = 0.006 for arterial hypertension). Concerning the occurrence of COVID-19 symptoms, patients under treatment with paracetamol had a shorter duration from symptom onset until ICU admission in comparison with patients without paracetamol medication (6 versus 7 days, p = 0.01). Additional data regarding patient demographics and co-morbidities are displayed in Table 1.

Treatment in intensive care units

We observed a significant difference in SOFA scores on ICU admission between the two groups: those who received paracetamol treatment were admitted with a slightly higher SOFA score compared to those without paracetamol intake (5 versus 5, IQR 3–8 versus 3–8; cf. Table 1; p = 0.004). Furthermore, we observed several differences in intensive care treatment: Patients on paracetamol treatment prior to ICU admission were significantly less often subjected to endotracheal intubation and vasopressor treatment (65% versus 71%, p < 0.001 and 63% versus 68%, p = 0.007, respectively). No difference in tracheostomy rates were observed (16% versus 19%, p = 0.073). Additionally, the need for renal replacement therapy and NIV did not differ between both groups (14% versus 15%, p = 0.3; 26% vs 27%, p = 0.58, respectively). Concerning treatment withholding and withdrawal, patients with a reported paracetamol intake were less likely to be subjected to either treatment withholding or withdrawal, such as discontinuing respiratory or circulatory support, when compared to those without paracetamol intake (25% versus 29%, p = 0.021; 16% versus 19%, p = 0.011, respectively).

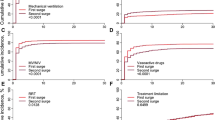

Mortality

No difference in mortality was observed between patients with and without paracetamol intake up to ten days prior to ICU admission (Fig. 1): ICU mortality was 46% vs 48% (p = 0.3) in patients with and without paracetamol intake respectively; 30-day mortality was 48% versus 51% (p = 0.12) in patients with and without paracetamol intake; 3-month mortality rates were 60% versus 64% (p = 0.059), respectively.

Sensitivity analyses stratifying 30-day-mortality into subgroups for patient-specific characteristics using logistic regression producing univariate odds ratios are shown in Fig. 2. The 30-day-mortality was similar between patients with and without paracetamol intake regardless of treatment limitations, the use of NIV, age strata and the time from symptom onset until admission. There was a trend towards higher mortality in patients with paracetamol intake without intubation and in vulnerable patients as assessed by CFS.

Sensitivity analyses stratifying 30-day-mortality in subgroups for patient-specific characteristics using logistic regression producing univariate odds ratios. The 30-day-mortality was similar between patients with and without paracetamol intake regardless of treatment limitations, the use of NIV, age strata and the time from symptom onset until admission. Patients categorized as vulnerable according to CFS (OR 0.36) and without endotracheal intubation and vasopressor use (OR 0.62, respectively) were more likely to take paracetamol

After adjustment for age, sex, SOFA score and CFS at admission, paracetamol use was not associated with ICU (aOR 0.93 95%CI 0.78–1.11; p = 0.42), 30-day (aOR 0.86 95%CI 0.72–1.03; p = 0.10) and 3-month (aOR 0.88 95%CI 0.72–1.07; p = 0.20) mortality.

Discussion

In this subgroup analysis of critically ill patients ≥ 70 years of age, we investigated the influence of prior paracetamol intake on short-term and long-term mortality in patients with COVID-19. At the beginning of the pandemic, on the 14th of March 2020, the French Ministry of Health published data on 400 patients suffering from a severe clinical course of COVID-19 after taking ibuprofen; it therefore advised against the use of ibuprofen and other NSAIDs as the analgesics and antipyretics of choice. Instead, several health experts advised the use of paracetamol in case of fever or pain [9, 19, 20]. Previous studies investigated possible pathophysiological mechanisms by which NSAIDs and paracetamol could influence the clinical course of an infection with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses [12, 21,22,23].

Paracetamol on the other hand is not included in the group of NSAIDs and has a more pronounced effect on cyclooxygenase (COX) 3 iso-enzyme, which is located in the central nervous system in contrast to the COX variants 1 and 2; thus, paracetamol has more central antipyretic and analgesic effects without compromising the systemic inflammatory cascade [24, 25]. Our findings are in line with current literature, confirming the safety of paracetamol as a potent analgesic and antipyretic drug in viral infections and especially in the case of COVID-19 disease [26, 27]. This is even true in a setting of critically ill and vulnerable, very old and frail people admitted to an ICU. We found no association of paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission with either ICU-, 30-day- and 3-months-mortality in patients with COVID-19 aged 70 years or more.

Since the study at hand did not report on analgesic use other than paracetamol, e.g., aspirin or NSAIDs, it remains unclear, whether paracetamol has any specific impact on the clinical course concerning the extent of intensive care treatment. Additionally, no differences in renal replacement therapy were observed. This may be explained by the mainly hepatic metabolism of paracetamol and a central activation of the COX 1 splice variant COX 3 as stated above [11, 24, 25, 28].

Patients on paracetamol treatment prior to hospitalization were also less prone to treatment withholding or withdrawal in comparison with those without paracetamol intake. In the light of the increased frailty of the paracetamol group, it remains unclear, why, despite this difference in co-morbidities, such as arterial hypertension and diabetes, they were less likely to have treatment withheld and withdrawn. This may be the result of the heterogeneity due to the international and multicentric setup of the COVIP study; hence individual differences, ethical, socio-medical patient backgrounds and the current epidemiological local burden of COVID-19 disease in the study sites must be considered, when discussing the observed differences in therapy and therapeutic limitations.

Our results are in line with findings by Park and colleagues, who showed safety of paracetamol in comparison to ibuprofen regarding the outcome of COVID-19 disease by analysing a propensity matched cohort of Korean patients in the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [29]. Similar results were published by Rinott et al. in a retrospective study on Israeli patients with a median age of 45 years, who reported ibuprofen or paracetamol intake up to 14 days prior to study inclusion; no difference in mortality or respiratory support rates were observed [30]. Further data on safety of paracetamol and NSAIDs were provided by Chandan and colleagues in a retrospective propensity matched study of 17,190 patients with osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom, who were prescribed either paracetamol and codeine, paracetamol and dihydrocodeine or NSAID: the study showed no increased risk of COVID-19 disease or mortality in both groups [31].

Importantly, we do neither observe paracetamols efficacy nor its safety in use. In summary, our multi-centre study suggests safety of paracetamol intake prior to hospitalization in intensive care units in a vulnerable and frail collective of more than 70 years old patients suffering from COVID-19 disease. This hypothesis is based on the evidence provided within this international, prospective multicentre study.

Limitations

Our study has some methodological limitations. Firstly, the study lacks a control group of younger patients admitted to ICU wards for severe COVID-19. Secondly, no control group of non-ICU patients age ≥ 70 was analyzed. Furthermore, data recording was only limited to time after ICU admission, thus leaving out information on pre-ICU care and possible triage. In addition, no detailed information on ICU equipment, quality of care, nurse-patient ratios and measure of staff stress was obtained; neither was paracetamol use during ICU treatment addressed. These local circumstances may affect the care of older ICU patients [32]. Also, participating countries varied widely in their care structure, thus resulting in a large heterogeneity in the level of care and the regional burden of care regarding local COVID-19 cases. Regarding paracetamol intake, we did not assess and document the doses of paracetamol ingested. Limitations of care in the pandemic surges did not allow to measure plasma metabolites and estimate true drug exposure, thus limiting data reliability. Lastly, our study did not analyze the intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen or aspirin and their corresponding impact on mortality and clinical course. Therefore, no recommendation towards a specific subgroup of analgesics can be made.

Conclusion

In the international multicentre COVIP study of old, critically ill patients with COVID-19, we found no association of paracetamol intake prior to ICU admission with short-term and 3-month mortality. Paracetamol is therefore likely safe for analgesic and antipyretic use in this group.

Availability of data and materials

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article are available to investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the COVIP steering committee. The anonymized data used and analyzed in this study can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request if required.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index (kg/m2)

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CFS:

-

Clinical Frailty Scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- COX:

-

Cyclooxygenase

- eCRF:

-

Electronic case report form

- FiO2 :

-

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- (a)OR:

-

(Adjusted) odds ratio

- paO2 :

-

Arterial partial oxygen pressure

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Score

References

Smorenberg A, Peters EJ, van Daele P, Nossent EJ, Muller M. How does SARS-CoV-2 targets the elderly patients? A review on potential mechanisms increasing disease severity. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;83:1–5.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42.

Nachtigall I, Lenga P, Jozwiak K, Thurmann P, Meier-Hellmann A, Kuhlen R, Brederlau J, Bauer T, Tebbenjohanns J, Schwegmann K, et al. Clinical course and factors associated with outcomes among 1904 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Germany: an observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(12):1663–9.

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–6.

Jung C, Flaatten H, Fjolner J, Bruno RR, Wernly B, Artigas A, Bollen Pinto B, Schefold JC, Wolff G, Kelm M, et al. The impact of frailty on survival in elderly intensive care patients with COVID-19: the COVIP study. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):149.

Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, Bagshaw SM, Boyd JG, Maslove D, Sibley S, Rockwood K. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(8):1105–22.

Hewitt J, Carter B, Vilches-Moraga A, Quinn TJ, Braude P, Verduri A, Pearce L, Stechman M, Short R, Price A, et al. The effect of frailty on survival in patients with COVID-19 (COPE): a multicentre, European, observational cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(8):e444–51.

Bubar KM, Reinholt K, Kissler SM, Lipsitch M, Cobey S, Grad YH, Larremore DB. Model-informed COVID-19 vaccine prioritization strategies by age and serostatus. Science. 2021;371(6532):916–21.

Day M. Covid-19: ibuprofen should not be used for managing symptoms, say doctors and scientists. BMJ. 2020;368: m1086.

Anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens (AINS) et complications infectieuses graves [https://ansm.sante.fr/actualites/anti-inflammatoires-non-steroidiens-ains-et-complications-infectieuses-graves#_ftn1]

Micallef J, Soeiro T, Jonville-Bera AP. French Society of Pharmacology T: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapie. 2020;75(4):355–62.

Robb CT, Goepp M, Rossi AG, Yao C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prostaglandins, and COVID-19. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(21):4899–920.

Drake TM, Fairfield CJ, Pius R, Knight SR, Norman L, Girvan M, Hardwick HE, Docherty AB, Thwaites RS, Openshaw PJM, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and outcomes of COVID-19 in the ISARIC Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK cohort: a matched, prospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(7):e498–506.

Flaatten H, De Lange DW, Morandi A, Andersen FH, Artigas A, Bertolini G, Boumendil A, Cecconi M, Christensen S, Faraldi L, et al. The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (>/= 80 years). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1820–8.

Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A, Leaver S, Watson X, Boulanger C, Szczeklik W, Artigas A, Morandi A, Andersen F, et al. The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: the VIP2 study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(1):57–69.

Bruno RR, Wernly B, Kelm M, Boumendil A, Morandi A, Andersen FH, Artigas A, Finazzi S, Cecconi M, Christensen S, et al. Management and outcomes in critically ill nonagenarian versus octogenarian patients. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):576.

Jung C, Bruno RR, Wernly B, Joannidis M, Oeyen S, Zafeiridis T, Marsh B, Andersen FH, Moreno R, Fernandes AM, et al. Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and COVID-19 in critically ill elderly patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7(1):76–7.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Iraqi W, Rossignol P, Angioi M, Fay R, Nuee J, Ketelslegers JM, Vincent J, Pitt B, Zannad F. Extracellular cardiac matrix biomarkers in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure: insights from the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS) study. Circulation. 2009;119(18):2471–9.

Little P. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and covid-19. BMJ. 2020;368: m1185.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80 e278.

Cabbab ILN, Manalo RVM. Anti-inflammatory drugs and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: Current knowledge and potential effects on early SARS-CoV-2 infection. Virus Res. 2021;291: 198190.

Voiriot G, Philippot Q, Elabbadi A, Elbim C, Chalumeau M, Fartoukh M. Risks Related to the Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adult and Pediatric Patients. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):786.

Chandrasekharan NV, Dai H, Roos KL, Evanson NK, Tomsik J, Elton TS, Simmons DL. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(21):13926–31.

Sharma CV, Mehta V. Paracetamol: mechanisms and updates. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):153–8.

von Philipsborn P, Biallas R, Burns J, Drees S, Geffert K, Movsisyan A, Pfadenhauer LM, Sell K, Strahwald B, Stratil JM, et al. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with viral respiratory infections: rapid systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11): e040990.

Crighton AJ, McCann CT, Todd EJ, Brown AJ. Safe use of paracetamol and high-dose NSAID analgesia in dentistry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br Dent J. 2020;229(1):15–8.

Dwyer JP, Jayasekera C, Nicoll A. Analgesia for the cirrhotic patient: a literature review and recommendations. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(7):1356–60.

Park J, Lee SH, You SC, Kim J, Yang K. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent use may not be associated with mortality of coronavirus disease 19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5087.

Rinott E, Kozer E, Shapira Y, Bar-Haim A, Youngster I. Ibuprofen use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(9):1259-e5.

Chandan JS, Zemedikun DT, Thayakaran R, Byne N, Dhalla S, Acosta-Mena D, Gokhale KM, Thomas T, Sainsbury C, Subramanian A, et al. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and Susceptibility to COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(5):731–9.

Flaatten H, deLange D, Jung C, Beil M, Guidet B. The impact of end-of-life care on ICU outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(5):624–5.

Acknowledgements

List of collaborators of the COVIP-study group.

Hospital | City | ICU | Name | |

Austria | ||||

Medical University Graz | Graz | Allgemeine Medizin Intensivstation | Philipp Eller | |

Medical University Innsbruck | Innsbruck | Division of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine | Michael Joannidis | |

Belgium | ||||

Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg | Genk | Department of Intensive Care | Dieter Mesotten | |

CHR Haute Senne | Soignies | Department of Intensive Care | Pascal Reper | |

Ghent University Hospital | Ghent | Department of Intensive Care | Sandra Oeyen | |

AZ Sint-Blasius | Dendermonde | Department of Intensive Care | Walter Swinnen | |

Clinique Saint Pierre Ottignies | Ottignies | Department of Intensive Care | Nicolas Serck | |

Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel | Brussel | ICU UZB | ELISABETH DEWAELE | |

Denmark | ||||

Herlev og Gentofte Hospital | Herlev | Intensiv Behandling | Helene Brix | |

Slagelse | Slagelse | Intensiv | Jens Brushoej | |

Regionshospitalet Horsens | Horsens | Intensiv | Pritpal Kumar | |

Odense University Hospital | Odense | Intensive Care Unit | Helene Korvenius Nedergaard | |

Sygehus Lillebælt | Kolding | Intensiv | Helene Korvenius Nedergaard | |

Regionshospitalet Viborg | Viborg | Intensiv | Ida Riise Balleby | |

Sygehus Sønderjylland | Aabenraa | Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care | Camilla Bundesen | |

Regionshospitalet Herning | Herning | Intensiv Afdeling | Maria Aagaard Hansen | |

Nordsjællands Hospital | Hillerød | Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care | Stine Uhrenholt | |

Regionshospitalet Randers | Randers | Intensiv | Helle Bundgaard | |

Aarhus University Hospital | Aarhus | Department of Intensive Care | Jesper Fjølner | |

England | ||||

Musgrove Park | Adult ICU | Taunton | Richard Innes | |

Princess Alexandra Hospital Harlow | Princess Alexandra Hospital ICU | Essex | James Gooch | |

Royal Papworth Hospital | Cardiothoracic Critical Care | Cambridge | Lenka Cagova | |

Royal Surrey Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | Intensive Care Unit | Guildford | Elizabeth Potter | |

Russells Hall | Russells Hall Anaes Dept | Dudley | Michael Reay | |

Tunbridge Wells Hospital | Tunbridge Wells Intensive Care/High Dependency Unit | Tunbridge Wells | Miriam Davey | |

Walsall Manor Hospital | Walsall ICU | Walsall | Mohammed Abdelshafy Abusayed | |

West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust | Critical Care | Bury St Edmunds | Sally Humphreys | |

France | ||||

Hôpital Privé Claude Galien | Quincy sous Sénart | Medico-surgical ICU | Arnaud Galbois | |

Saint Antoine | Paris | Medical ICU | Bertrand Guidet | |

Hôpital Ambroise Paré | Boulogne Billancourt | Medico-urgical ICU | Cyril Charron | |

Hopital Européen Georges Pompidou | Paris | Medical ICU | Caroline Hauw Berlemont | |

CHU de Besançon | Besançon | Medico-surgical ICU | Guillaume Besch | |

Dieppe General Hospital | Dieppe | Medical ICU | Jean-Philippe Rigaud | |

CHU Amiens | Amiens | Medical ICU | Julien Maizel | |

Tenon | Paris | Medico-surgical ICU | Michel Djibré | |

Clinique Du Millenaire | Montpellier | Surgical ICU | Philippe Burtin | |

Marne La Vallee | Jossigny | Medico-surgical ICU | Pierre Garcon | |

CHU Lille | Lille | Medical ICU | Saad Nseir | |

CHU de Caen | Caen | Medical ICU | Xavier Valette | |

Compiegne Noyon Hospital | Compiegne | Medico-surgical ICU | Nica Alexandru | |

Cochin | Paris | Medical ICU | Nathalie Marin | |

CH Pau | Pau | Medico-surgical ICU | Marie Vaissiere | |

Victor Dupouy | Argenteuil | Medico-surgical ICU | Gaëtan PLANTEFEVE | |

CH Saint Philibert | Lomme lez Lille | Medical ICU | Thierry Vanderlinden | |

Beaujon | Clichy | Medico-surgical ICU | Igor Jurcisin | |

Lariboisière | Paris | Medical ICU | Buno Megarbane | |

Lariboisière | Paris | Surgical ICU | Benjamin Glenn Chousterman | |

Saint-Louis | Paris | Surgical ICU | François Dépret | |

Saint Antoine | Paris | Surgical ICU | Marc Garnier | |

Louis Mourier | Colombes | Medico-surgical ICU | Sebastien Besset | |

Avicenne | Bobigny | Medico-surgical ICU | Johanna Oziel | |

Centre hospitalier de Versailles | Le Chesnay | Medico-surgical ICU | Alexis Ferre | |

Robert Debré | Paris | Pediatric ICU | Stéphane Dauger | |

Saint-Louis | Paris | Medical ICU | Guillaume Dumas | |

Sainte-Anne | Paris | Medico-surgical ICU | Bruno Goncalves | |

CHU de Besancon | Besançon | Medical ICU | Lucie Vettoretti | |

CH Dr SCHAFFNER, Reanimation polyvalente | Lens | Medico-surgical ICU | Didier Thevenin | |

Germany | ||||

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | 44i | Stefan Schaller | |

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | W1 | Stefan Schaller | |

Florence-Nightingale Krankenhaus | Duesseldorf | 32 | Muhammed Kurt | |

Kliniken Nordoberpfalz AG Klinikum Weiden | Weiden | Interdisziplinäre Intensivmedizin | Andreas Faltlhauser | |

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | 8i | Stefan Schaller | |

Evangelisches Krankenhaus Düsseldorf | Düsseldorf | Intensivstation | Christian Meyer | |

Malteser Krankenhaus St. Franziskus Hospital | Flensburg | Intensivstation 1 | Milena Milovanovic | |

Uniklinik Schleswig Holstein Campus Kiel | Kiel | Internistische Intensivstation | Matthias Lutz | |

Johanna Etienne Krankenhaus | Neuss | Station 2 | Gonxhe Shala | |

Kliniken Maria Hilf | Mönchengladbach | Internistische Intensivstation I und II | Hendrik Haake | |

Krankenhaus Bethanien GmbH Solingen | Solingen | Intensivpflege Bethanien | Winfried Randerath | |

Uniklinik Düsseldorf | Düsseldorf | MX01 | Anselm Kunstein | |

University Hospital Würzburg | Würzburg | Patrick Meybohm | ||

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | 43i | Stefan Schaller | |

St Vincenz | Limburg | ICU | Stephan Steiner | |

University Hospital Ulm | Ulm | IOI-Interdisziplinäre Operative Intensivmedizin | Eberhard Barth | |

Marienhospital Aachen | Aachen | ITS | Tudor Poerner | |

University Hospital Leipzig / Klinik und Poliklinik für Anästhesiologie und Intensivtherapie | Leipzig | IOI (Interdisciplinary Operational/Surgical ICU) | Philipp Simon | |

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | 203i | Marco Lorenz | |

Städtische Kliniken Mönchengladbach | Mönchengladbach | Interdisziplinäre Intensivstation | Zouhir Dindane | |

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Berlin | 144i | Karl Friedrich Kuhn | |

Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH | Darmstadt | Interdiszipinaere Operative Intensivstation Klinik fuer Anaesthesiologie und operative Intensivmedizin | Martin Welte | |

Elisabeth-Krankenhaus Essen | Essen | Kardiologisch-internistische Intensivstation | Ingo Voigt | |

Klinikum Konstanz | Konstanz | I01 | Hans-Joachim Kabitz | |

Medical Center - University of Freiburg | Freiburg | Anaesthesiologiesche Intensivtherapiestation | Jakob Wollborn | |

St. Franziskus-Hospital Münster | Münster | Klinik für Anästhesie und operative Intensivmedizin | Ulrich Goebel | |

University Hospital Cologne | Cologne | Surgical ICU of the Department of Anesthesiology | Sandra Emily Stoll | |

University Hospital Duesseldorf | Duesseldorf | CIA1 | Detlef Kindgen-Milles | |

Essen University Hospital | Essen | Ana Int | Simon Dubler | |

University Hospital Duesseldorf | Düsseldorf | MI1/2 | Christian Jung | |

Rechts der Isar Technical University | Munich | ICU 1 | Kristina Fuest | |

Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz | Mainz | Anästhesie-Intensivstation | Michael Schuster | |

Greece | ||||

GENERAL HOSPITAL OF LARISSA | LARISSA | ICU | Antonios Papadogoulas | |

General University Hospital of Patras | Patras | ΜΕΘ | Francesk Mulita | |

Sotiria Hospital National and Kapodistrian University of Athens | Athens | ICU 1st Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Dpt | Nikoletta Rovina | |

Ught Ahepa | Thessaloniki | Metha | Zoi Aidoni | |

UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL (ATTIKON) | HAIDARI | 2nd DEPARTMENT OF CRITICAL CARE | EVANGELIA CHRISANTHOPOULOU | |

UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL OF HERAKLION | HERAKLION | ICU UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL OF HERAKLION | EUMORFIA KONDILI | |

UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL OF IOANNINA | IOANNINA | INTENSIVE CARE UNIT | Ioannis Andrianopoulos | |

Netherland | ||||

Alrijne Zorggroep | Leiderdorp | ICU Department | Martijn Groenendijk | |

Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital | Nijmegen | C38 | Mirjam Evers | |

Canisius Wilhelmlina Ziekenhuis | Nijmegen | ICU Department | Mirjam Evers | |

Diakonessenhuis Utrecht | Utrecht | Diakonessenhuis | Lenneke van Lelyveld-Haas | |

Haga Ziekenhuis | The Hague | ICU Haga | Iwan Meynaar | |

Medisch Spectrum Twente | Enschede | Intensive Care Center | Alexander Daniel Cornet | |

Radboudumc | Nijmegen | Intensive Care department Radboudumc | Marieke Zegers | |

University Medical Center Groningen | Groningen | Department of Critical Care | Willem Dieperink | |

University Medical Center Utrecht | Utrecht | Intensive Care | Dylan de Lange | |

Zuyderland mc | Heerlen | Intensive Care | Tom Dormans | |

Norway | ||||

Haugesund Hospital | Haugesund | ICU | Michael Hahn | |

Haukeland University Hospital | Bergen | KSK-ICU | Britt Sjøbøe | |

Kristiansund Hospital Helse Møre og Romsdal HF | Kristiansund | ICU | Hans Frank Strietzel | |

Oslo University Hospital | Oslo | Surgical ICU | Theresa Olasveengen | |

Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet Medical | Oslo | Department of Critical Care and Emergencies | Luis Romundstad | |

Ålesund Hospital | Ålesund | Dept. Anesthesia and Intensive Care Surgical ICU | Finn H. Andersen | |

Poland | ||||

Clinical Hospital Heliodor Święcicki Medical University of Karol Marcinkowski in Poznan | Poznan | Anesthesiology Intensive Therapy and Pain Treatment | Anna Kluzik | |

Infant Jesus Clinical Hospital Medical University of Warsaw | Warsaw | I Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care | Paweł Zatorski | |

Jagiellonia University Hospital Cracow | Cracow | Tomasz Drygalski | ||

Military Hospital | Krakow | ICU | Wojciech Szczeklik | |

Military Institute of Medicine | Warsaw | COVID-19 ICU | Jakub Klimkiewicz | |

Pomeranian Medical University | szczecin | ICU | Joanna Solek-pastuszka | |

Provincial Specialist Hospital | Olsztyn | Department of Intensive Care | Dariusz Onichimowski | |

SPSK-1 | Lublin | II Klinika Anestezjologii i Intensywnej Terapii | Miroslaw Czuczwar | |

University Hospital in Opole | Opole | Department of Anesthesiology and Intensvie Care | Ryszard Gawda | |

Uniwersyteckie Centrum Kliniczne w Gdańsku | Gdańsk | Klinika Anestezjologii i Intensywnej Terapii | Jan Stefaniak | |

Voivodship Hospital in Poznan | Poznan | Intensive Care Unit | Karina Stefanska-Wronka | |

ZDROWIE Sp. z o.o. | Kwidzyn | Oddział Anestezjologii i Intensywnej Terapii | Ewa Zabul | |

Portugal | ||||

Centro Hospitalar de Tondela-Viseu EPE | Viseu | Unidade de Cuidados Intensivos Polivalente | Ana Isabel Pinho Oliveira | |

Centro Hospitalar do Médio Tejo | Abrantes | Serviço de Medicina Intensiva | Rui Assis | |

Centro Hospitalar e Universitário São João | Porto | Infectious Diseases ICU | Maria de Lurdes Campos Santos | |

Centro Hospitalar Tráz os Montes e Alto Dour | Vila Real | D | Henrique Santos | |

Curry Cabral Hospital | Lisbon | UCIP | Filipe Sousa Cardoso | |

Hospital de Beatriz Ângelo | Loures | Serviço de Medicina Intensiva | André Gordinho | |

Spain | ||||

Clínico Universitario Lozano-Blesa | Zaragoza | Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos | M José Arche Banzo | |

Clínico Universitario Lozano-Blesa | Zaragoza | Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos | Begoña Zalba-Etayo | |

COMPLEJO ASISTENCIAL DE SEGOVIA | SEGOVIA | UCI SEGOVIA | PATRICIA JIMENO CUBERO | |

Complexo Hospitalario Universitario Ourense | Ourense | UCI CHUO | Jesús Priego | |

Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Sabadell | Parc Taulí | Gemma Gomà | |

Germans Trias i Pujol | Badalona | General ICU | Teresa Maria Tomasa-Irriguible | |

H. Universitari i Politècnic La Fe | Valencia | General ICU | Susana Sancho | |

Hospital Alvaro Cunqueiro | Vigo | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva CHUVI | Aida Fernández Ferreira | |

Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta | Tortosa | Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos | Eric Mayor Vázquez | |

Hospital General Universitario de Albacete | Albacete | aapm111 | Ángela Prado Mira | |

Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor | Barcelona | ICU | Mercedes Ibarz | |

Hospital Universitario de Burgos | Burgos | UCI Burgos | David Iglesias | |

Hospital Universitario de Getafe | Getafe | Getafe | Susana Arias-Rivera | |

Hospital Universitario de Getafe | Getafe | Medical-Surgical ICU | Fernando Frutos-Vivar | |

Hospital universitario Rey Juan Carlos | Mostoles | Cuidados intensivos | Sonia Lopez-Cuenca | |

Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega | Valladolid | Reanimación Quirurgica | Cesar Aldecoa | |

Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | Valladolid | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva - Unidad 1 | David Perez-Torres | |

Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | Valladolid | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva - Unidad 2 | Isabel Canas-Perez | |

Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | Valladolid | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva - Unidad 3 | Luis Tamayo-Lomas | |

Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | Valladolid | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva - Unidad 4 | Cristina Diaz-Rodriguez | |

Miguel Servet University Hospital | Zaragoza | Servicio de Medicina Intensiva | Pablo Ruiz de Gopegui | |

Switzerland | ||||

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois | Lausanne | Service de Médecine Intensive Adulte (SMIA) | Nawfel Ben-Hamouda | |

Clinica Luganese Moncucco | Lugano | Servizio di anestesia e rianimazione | Andrea Roberti | |

Fribourg Hospital | Fribourg | Intensive Care Unit | Yvan Fleury | |

Geneva University Hospitals | Geneva | Department of Acute Medicine | Nour Abidi | |

Inselspital Bern | Bern | Universitätsklinik für Intensivmedizin | Joerg C. Schefold | |

Kantonspital Thurgau Frauenfeld | Frauenfeld | Institut für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin | Ivan Chau | |

Kantonspital Thurgau Frauenfeld | Frauenfeld | Institut für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin | Alexander Dullenkopf | |

Wales | ||||

Glan Clwyd Hospital | Bodelwyddan | Critical Care Unit | Richard Pugh | |

Wrexham Maelor Hospital | Wrexham | Critical Care | Sara Smuts | |

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Free support for running the electronic database and was granted from the Department of Epidemiology, University of Aarhus, Denmark. The support of the study in France by a grant from Fondation Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris pour la recherche is greatly appreciated. In Norway, the study was supported by a grant from the Health Region West. In addition, the study was supported by a grant from the European Open Science Cloud (EOSC). EOSCsecretariat.eu has received funding from the European Union's Horizon Programme call H2020-INFRAEOSC-05–2018-2019, grant agreement number [831644]. This work was supported by the Forschungskommission of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf, No. [2018-32] to GW and No. [2020-21] to RRB for a Clinician Scientist Track. No (industry) sponsorship has been received for this investigator-initiated study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

PHB, BW and CJ analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HF and BG and DL contributed to statistical analysis and improved the paper. MK and MB and RRB and SB and GW and RE and SS and PVvH and ME and MJ and AA and BG and FHA and SL and JF and BM and RM and SO and BP and WS and JCS gave guidance and improved the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The primary competent ethics committee was the Ethics Committee of the University of Duesseldorf, Germany (application number 2020–892). Each participating center received a copy of the study protocol. Institutional research ethic board approval was obtained from each study site and was mandatory for study participation.

Due to the observational nature of the study, participation in this study did not impact medical procedures, which were all executed in accordance with the relevant medical guidelines and regulations. No additional examinations, e.g., sampling and storage of biomaterials, such as blood or CT-scans and X-rays, were performed.

The study was planned in adherence to the European Union General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) directive, which is implemented in most participating countries. Deceased patients were included within strict consideration of local requirements set up by the local ethics committees. However, in a few countries, recruitment was possible without informed consent in accordance with the respective local ethics committee (see above).

Consent for publication

The manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. JCS reports grants (full departmental disclosure) from Orion Pharma, Abbott Nutrition International, B. Braun Medical AG, CSEM AG, Edwards Lifesciences Services GmbH, Kenta Biotech Ltd, Maquet Critical Care AB, Omnicare Clinical Research AG, Nestle, Pierre Fabre Pharma AG, Pfizer, Bard Medica S.A., Abbott AG, Anandic Medical Systems, Pan Gas AG Healthcare, Bracco, Hamilton Medical AG, Fresenius Kabi, Getinge Group Maquet AG, Dräger AG, Teleflex Medical GmbH, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck Sharp and Dohme AG, Eli Lilly and Company, Baxter, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring, Novartis, Covidien, Philips Medical, Phagenesis Ltd, Prolong Pharmaceuticals and Nycomed outside the submitted work. The money went into departmental funds. No personal financial gain applied.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Baldia, P.H., Wernly, B., Flaatten, H. et al. The association of prior paracetamol intake with outcome of very old intensive care patients with COVID-19: results from an international prospective multicentre trial. BMC Geriatr 22, 1000 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03709-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03709-w