Abstract

Background

This study investigated the association between xerostomia and health risk behaviours, general and oral health and quality of life.

Methods

A cross-sectional study involving 800 adults over 65 years of age residing in Spain using a computer-assisted telephone questionnaire. The severity of xerostomia was assessed through the Xerostomia Inventory (XI). Both univariate and adjusted multinomial logistic regression were used to determine the risk (OR) of xerostomia.

Results

The sample comprised of 492 females (61.5%) and 308 males, with a mean age of 73.7 ± 5.8 years. Some, 30.7% had xerostomia: 25.6% mild, 4.8% moderate and 0.3% severe, the majority being female (34.8% vs 24%; p = 0.003). The mean XI was 24.6 ± 6.3 (95% CI 19.2–24.8) for those with poor health, whereas it was 17.4 ± 6.3 (95%CI 16.1–18.6) in those reporting very good health (p < 0.001). This difference was also observed in terms of oral health, with the XI mean recorded as 14.7 ± 10.7 for very poor oral health and 6.4 ± 5.4 for those with very good health (p = 0.002). Logistic regression showed that the highest OR for xerostomia was observed among adults with poor general health (2.81; 95%CI 1.8–4.3; p < 0.001) and for adjusted model the OR was still significant (2.18; 95%CI 1.4–3.4; p = 0.001). Those who needed help with household chores had 2.16 higher OR (95%CI 1.4–3.4; p = 0.001) and 1.69 (95%CI 1.1–2.7; p = 0.03) in the adjusted model. Females had a higher risk of suffering from xerostomia than males.

Conclusion

The strong association between xerostomia and the general and oral health status of older adults justifies the need for early assessment and regular follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The world’s population is ageing at a much faster rate than ever before, and it is estimated that between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years of age will increase from 12 to 22% [1]. Xerostomia (or the feeling of dry mouth) mainly affects older people and may be due to a variety of underlying etiologies [2]. Older people have more comorbidities, meaning that a high proportion are polymedicated. It is estimated that so-called “polypharmacy” affects 40–50% of the older population in high-income countries [3], and it is a well-known cause of hyposalivation and xerostomia [2].

Alcohol use disorders in the geriatric population are considered to be the “invisible epidemic” [4]. The European Union has the highest rate of alcohol consumption in the world, with a seemingly low perception of the associated risks [5]. Alcohol ingestion inhibits the release of the antidiuretic hormone, resulting in body dehydration [6], likewise, it also causes salivary gland atrophy and is one of the main causes of sialadenosis [7]. Smoking also has this same effect, and preliminary studies have shown that long-term smoking is significantly associated with hyposalivation [8]. Profound and complex interactions exist between nutrition and oral health [9], however, to our knowledge, no existing studies have considered the relationship between diet in older people and the sensation of dry mouth, although Machowicz et al. [10] associated adherence to a Mediterranean diet with a lower probability of suffering from primary Sjögren’s Syndrome.

The relationship between oral and general health has been widely discussed in scientific literature and it is known that poor oral health can increase the risk of certain physical disorders [11]. A meta-analysis published in 2021 found a positive association between poor general health and poor oral health-related quality of life among older adults [12]. In a systematic map of systematic reviews that examined current knowledge about older persons’ oral health status and dental care, it is concluded that there is an urgent need for research within most domains in geriatric dentistry [13].

The aim of this study was to analyse the association between xerostomia and health risk behaviours, general and oral health and oral health-related quality of life among a large representative sample of adults over 65 years of age.

Methods

Data came from the 2020 SEGER (Spanish society of Gerodontology) Survey, a national survey following the STROBE guidelines for observational studies [14].

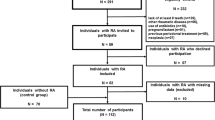

The target population included men and women over the age of 65, with significant representation throughout Spain. Simple random sampling was performed at the national level, with proportional stratification by geographic area. Data were collected anonymously, and the study was granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela.

Survey design

A computer-assisted telephone survey (CATI research method: Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing) was conducted using a structured questionnaire (interview length: 16 minutes). This questionnaire comprised five sections that includes information related with: Social-demographic data; General and oral health; Oral problems during 2019; Tobacco and alcohol consumption and Dietary habits.

Variables

The Xerostomia Inventory (XI) was used to assess dry mouth sensation, designed in 1999 [15] using the validated Spanish version [16]. The ranges of values associated with each degree were as follows: 0–11: No xerostomia, 12–22: Mild xerostomia, 23–33: Moderate xerostomia, and 34–44: Severe xerostomia [17]. In relation to health risk behaviours, tobacco use has been assessed (former or current, number of cigarettes smoked and, for ex-smokers, years since they gave up smoking) as well as alcohol consumption (type of alcoholic beverages and frequency) and dietary habits (frequency of vegetables, legumes, fruit, white meat (chicken, rabbit, turkey), red meat (beef, pork, lamb) and daily drinking water). In relation to general and oral health, concerns about own general and oral health status and perception of own general and oral health were assessed following a 5-point Likert scale. With regard to oral health-related quality of life, it was assessed in terms of oral problems during 2019.

The variables eligible for inclusion in the model, namely “general health” and “oral health”, were split into two by considering “poor or very poor” as poor, and “acceptable, good or very good” as good, for the multilevel binary logistic regression.

Statistical analysis

Contingency tables analysed the associations between categorical variables using a chi-squared test. Parametric statistics were used to describe the differences in the means, using the ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-hoc correction for comparisons with more than two elements. Both univariate and adjusted multinomial logistic regression were used to determine the Odds Ratio (OR) of xerostomia. A Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) has been constructed by using the version 0.2.7 of the R package ggdag (R Core Team, 2022). It provides a visual representation of causal relationships among the set of variables involved in the adjusted multinomial logistic regression. The data were analyzed with the SPSS v.28.00 (IBM, Madrid, Spain). The significance level was p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The sample comprised 492 females (61.5%) and 308 males (38.5%) with a mean age of 73.7 years (SD = 5.8). The complete descriptive data are in Table 1 and their territorial distribution is outlined in Fig. 1.

Xerostomia

Some 30.7% of the respondents suffered from xerostomia, most of whom were females (34.8% vs 24% in males) (p = 0.003). There were 25.6% with a mild degree of xerostomia, 4.8% moderate and 0.3% severe. The mean XI score was 8.9 ± 6.8. The mean XI was lower with better overall health, so it was 24.6 ± 6.3 (95% CI 19.2–24.8) for poor health, but 17.4 ± 6.3 (95% CI 16.1–18.6) for very good health (p < 0.001 Bonferroni test). This pattern was also observed in terms of oral health, with the XI mean recorded as 14.7 ± 10.7 for very poor oral health versus 6.4 ± 5.4 for very good (p = 0.002) (Table 2). The full data for the Xerostomia Inventory are found in Table 3.

General and oral health

There were 74.4% of respondents reporting acceptable or good general health and only 12.9% stated that their health was poor or very poor. The incidence of xerostomia in people with poor general health was 54.3% as opposed to 17.2% in people with good health (p < 0.001). There were 84.7% of respondents reporting acceptable or good oral health, with only 5.5% reporting that their oral health was poor or very poor. Of those who claimed to have poor oral health, 54.3% had xerostomia, unlike 20.5% of those who considered that their oral health is very good (p < 0.001). Xerostomia degree was higher among those who expressed greater concerns about their oral health, with an incidence of 46% among those who expressed great concern about this aspect, compared with just 18.9% of those who stated that they were not concerned about their oral health (p < 0.001). With regards to quality of life, 15.9% reported that they had problems with their mouth, teeth or dentition; 14.6% that they had difficulty eating; 13.9% that they experience tooth or gum pain, and 7% that they had avoided smiling or talking because of the appearance of their teeth or dentition. The percentage of xerostomia was higher (p < 0.001) the higher the frequency with which oral issues were suffered. In fact, 100% of people who stated that they avoided smiling or talking on a very frequent basis had a certain degree of xerostomia, whereas 28.7% stated that they never avoided said actions (p < 0.001).

Health risk behaviours: tobacco, alcohol and dietary habits

There were 54.1% who stated that they had never smoked, while 36.9% declared that they were ex-smokers, with the majority having given up smoking more than 15 years ago, and only 8.9% stated that they currently smoke. The number of non-smokers was higher among women and among those over the age of 74 years (p < 0.001).

Of those interviewed, 46.9% stated that they consume alcoholic beverages occasionally, and 17.5% that they do so on a daily basis, mainly wine, consuming around 1 or 2 drinks a day (7.8 and 3.8% respectively). Furthermore, 35.1% stated that they do not consume any alcohol at all, and this percentage was higher among women (47.5% vs 18.2%) (p < 0.001). With regards to tobacco and alcohol consumption, no significant differences were observed in terms of xerostomia.

Most of the participants stated that they consume fruit and vegetables on a daily basis (89 and 56.3% respectively), as opposed to their less frequent consumption of meat and legumes (only 0.6% stated that they consume red meat every day and, likewise, this figure was 2.5% for white meat, and 7.1% for legumes). As regards the consumption of red meat, there was a significant difference between men and women (p < 0.001), with the latter consuming less red meat. Among those who stated that they never consume vegetables, the percentage of xerostomia was 42.9%, but 28.9% for those who consume said products on a daily basis (p < 0.001). The incidence of xerostomia among individuals who stated that they never consume legumes was 55.6% but 29.2% for those who consume legumes every two or three days (p < 0.001).

The relation between the main studied variables has been illustrated in Fig. 2 by a DAG. The influence of general and oral health and health risk behaviours can be graphically observed.

Logistic regression analysis

Logistic regression showed that the highest OR for xerostomia was observed among adults with poor general health, who had 2.81 higher odds of suffering from this condition (95%CI 1.8–4.3, p < 0.001) than those in good health. In the model adjusted for gender, oral health, education, employment and household chores, the OR was 2.18 (95%CI 1.4–3.4, p = 0.001). Those who need help with household chores had 2.16 higher odds of suffering xerostomia (95%CI 1.4–3.4; p = 0.001) and the OR was 1.69 (95%CI 1.1–2.7; p = 0.03) in the adjusted model. Females had higher odds of suffering from xerostomia than males in both the univariate and multivariate models. Overall, adults with poor oral health had higher odds of suffering from this condition (Table 4).

Discussion

Our findings indicate a strong association between xerostomia (assessed using XI) and general and oral health. We found that the prevalence of xerostomia was 30.6%. Women had a higher risk of suffering from xerostomia than men. Poor general and oral health have been reported as risk factors for xerostomia. Regarding alcohol and tobacco consumption, the results were quite heterogeneous and we did not observe any variation in relation to xerostomia. A lower perception of xerostomia was observed among those who consume vegetables and legumes on a regular basis.

When interpreting the findings of this study it is important to consider certain limitations. Firstly, given its cross-sectional nature, it is not possible to prove causality, which would be ideal for clinical translation, therefore emphasizing the need for prospective longitudinal studies. Nevertheless, this research has notable strengths, such as a large sample size and the fact that our findings were drawn from a very specific group by age range (over 65 years of age) residing in different areas of Spain.

The prevalence of xerostomia was close to the findings reported by other international organizations, which put it between 20 and 30% [18]. In Australia, an incidence of 26.5% was reported among people over 75 years of age [19]. Among participants aged 20 to 80 years, Nederfors et al., observed a significant difference in incidence (21.3% in men and 27.3% in women) which increased substantially with age [18]. A recent prospective study among younger participants (aged 20–59 years) revealed that general health affects episodes of xerostomia [20]. Although in our study the majority of the respondents claimed to have an acceptable or good oral health status, in the systematic review by Wong et al. [21], the oral hygiene and oral health of older adults was reported to be poor. The explanation for this apparent contradiction could be that self-perceived health is often better than objectively observed health. Furthermore, self-reporting of general and oral health, as well as health risk behaviours may be biased by social desirability, which may lead to inaccurate self-reports and erroneous conclusions. Heberto et al. [22] have observed a high bias in reporting food intake. However, in a study published in 2020 [23], it has been reported that there is no significant association between social desirability bias and general medical beliefs or self-reported health. Methods to decrease this bias include writing and prefacing questions [24], which were designed by gerodontology experts in this study. In terms of the quality of life, as other authors have also observed [25, 26], xerostomia has a significant negative impact on the older population’s quality of life.

According to the “Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health” 2018 [27], 43% of the world’s population are current drinkers, while in our sample 64.4% reported drinking alcohol occasionally or daily. Wine was the most consumed beverage (14.4% of daily consumers), followed by beer, while only 2.1% stated that they consume spirits every day. This consumption pattern is very different to the one observed worldwide, where 44.8% of all recorded alcohol consumption was in the form of spirits, followed by beer and wine [27]. Several studies have shown that the use of alcohol or alcohol-free mouthwashes does not significantly affect xerostomia [28, 29]. We also did not find any relevant differences in terms of tobacco use and xerostomia severity, although preliminary studies have found that smoking significantly increases symptoms of xerostomia [8]. In studies of younger populations (under 60 years of age), smoking has also been found to increase the likelihood of suffering from regular xerostomia [20]. Xerostomia’s relationship with tobacco and alcohol remains unclear [30], however, whether or not these health risk behaviours play a relevant role in the development of xerostomia, there should be avoided as there is evidence that they do play a significant role in the development of oral cancer and other systemic diseases. A healthy diet should be advised and collaboration from doctors and dentists is essential in dietary interventions; indeed, dentists may be the earliest healthcare providers to detect an eating disorder [31]. Dentistry enables older adults to follow a satisfactory diet by restoring dental function and, as oral health improves, there is an opportunity to promote a good diet among this population group.

A cooperative approach involving different healthcare professionals in geriatric caregiving makes it possible to adjust to the individual needs of older patients [32, 33]. In this sense, our study updated and built on the current knowledge on the subject by providing evidence of xerostomia’s relationship with general and oral health in Spain. Although, mild cognitive impairment can be assumed in the participants, it was not assessed objectively as it requires a clinical diagnosis aided by a complete medical record, neurological examination, mental status examination and formal neuropsychological testing [34].

Our findings can probably be extrapolated to the rest of Europe. In Norway and Sweden, a dramatically increased incidence of xerostomia has also been reported amongst older patients, which must be taken into account in the clinical management of these individuals. It has also been pointed out that the comorbidity between xerostomia and oral pathologies must not be ignored in older adults [35,36,37].

In conclusion, we found a strong association between general and oral health with xerostomia in older adults, so this relationship should be taken into account when providing health care to this group. The findings of our study showed the value of focusing on general and oral health when detecting xerostomia in older people, as well as periodic assessment of xerostomia in patients with poor health.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article (and its additional file).

References

WHO: World Health Organitation 2021: World Health Organitation 2021. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/envejecimiento-y-salud

Millsop JW, Wang EA, Fazel N. Etiology, evaluation, and management of xerostomia. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(5):468–76.

Charlesworth CJ, Smit E, Lee DSH, Alramadhan F, Odden MC. Polypharmacy among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States: 1988-2010. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(8):989–95.

Kalapatapu RK, Paris P, Neugroschl JA. Alcohol use disorders in geriatrics. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40(3):321–37.

Pérez-González A, Lorenzo-Pouso A, Gándara-Vila P, Blanco-Carrión A, Somoza-Martín J, García-Carnicero T, et al. Counselling toward reducing alcohol use, knowledge about its morbidity and personal consumption among students of medical and dental courses in North-Western Spain. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021;27(1):e59–67.

Roberts KE. Mechanism of dehydration following alcohol ingestion. Arch Intern Med. 1963;112:154–7.

Enberg N, Alho H, Loimaranta V, Lenander-Lumikari M. Saliva flow rate, amylase activity, and protein and electrolyte concentrations in saliva after acute alcohol consumption. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92(3):292–8.

Dyasanoor S, Saddu SC. Association of Xerostomia and Assessment of salivary flow using modified Schirmer test among smokers and healthy individuals: a Preliminutesary study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(1):211–3.

Walls AWG, Steele JG. The relationship between oral health and nutrition in older people. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(12):853–7.

Machowicz A, Hall I, de Pablo P, Rauz S, Richards A, Higham J, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk of Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(4):216–21.

van der Putten GJ. The relationship between oral health and general health in the elderly. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2019;126(12):653–6.

Baniasadi K, Armoon B, Higgs P, Bayat A, Mohammadi Gharehghani MA, Hemmat M, et al. The Association of Oral Health Status and socio-economic determinants with Oral health-related quality of life among the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2021;19(2):153–65.

Ástvaldsdóttir Á, Boström A, Davidson T, Gabre P, Gahnberg L, Sandborgh Englund G, et al. Oral health and dental care of older persons-a systematic map of systematic reviews. Gerodontology. 2018;35(4):290–304.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Thomson WM, Chalmers JM, Spencer AJ, Williams SM. The xerostomia inventory: a multi-item approach to measuring dry mouth. Community Dent Health. 1999;16(1):12–7.

Serrano C, Fariña MP, Pérez C, Fernández M, Forman K, Carrasco M. Translation and validation of a Spanish version of the xerostomia inventory. Gerodontology. 2016;33(4):506–12.

Pérez-González A, Suárez-Quintanilla J, Otero-Rey E, Blanco-Carrión A, Gómez-García F, Gándara-Vila P, et al. Association between xerostomia, oral and general health, and obesity in adults. A cross-sectional pilot study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021;26(6):e762–9.

Nederfors T, Isaksson R, Mörnstad H, Dahlöf C. Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population--relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25(3):211–216.

Jamieson LM, Thomson WM. Xerostomia: its prevalence and associations in the adult Australian population. Aust Dent J. 2020;65(Suppl 1):S67–70.

da Silva L, Kupek E, Peres KG. General health influences episodes of xerostomia: a prospective population-based study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45(2):153–9.

Wong FMF, Ng YTY, Leung WK. Oral health and its associated factors among older institutionalized residents—a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(21).

Hebert JR, Clemow L, Pbert L, Ockene IS, Ockene JK. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(2):389–98.

Latkin CA, Edwards C, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict Behav. 2017;73:133–6.

Wan B, Ball P, Jackson D, Maynard G. Subjective health, general medicine beliefs and social desirability response among older hospital outpatients in Hong Kong. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020;28(5):498–505.

Herrmann G, Müller K, Behr M, Hahnel S. Xerostomia and its impact on oral health-related quality of life. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;50(2):145–50.

Matear DW, Locker D, Stephens M, Lawrence HP. Associations between xerostomia and health status indicators in the elderly. J R Soc Promot Heal. 2006;126(2):79–85.

WHO Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639.

Nair R, Chiu SE, Chua YK, Dhillon IK, Li J, Fai YT, et al. Should short-term use of alcohol-containing mouthrinse be avoided for fear of worsening xerostomia? J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(2):140–6.

Kerr AR, Katz RW, Ship JA. A comparison of the effects of 2 commercially available nonprescription mouthrinses on salivary flow rates and xerostomia. Quintessence Int. 2007;38(8):e440-7.

Villa A, Polimeni A, Strohmenger L, Cicciù D, Gherlone E, Abati S. Dental patients' self-reports of xerostomia and associated risk factors. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(7):811–6.

Kisely S, Baghaie H, Lalloo R, Johnson NW. Association between poor oral health and eating disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(4):299–305.

Da Mata C, Allen F. Time for routine use of minimum intervention dentistry in the elderly population. Gerodontology. 2015;32(1):1–2.

Barbe AG. Medication-induced xerostomia and Hyposalivation in the elderly: culprits, complications, and management. Drugs Aging. 2018;35(10):877–85.

Tangalos EG, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment in geriatrics. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(4):563–89.

Åstrøm AN, Lie SA, Ekback G, Gülcan F, Ordell S. Self-reported dry mouth among ageing people: a longitudinal, cross-national study. Eur J Oral Sci. 2019;127(2):130–8.

Johansson A, Johansson A, Unell L, Ekbäck G, Ordell S, Carlsson GE. Self-reported dry mouth in 50- to 80-year-old swedes: longitudinal and cross-sectional population studies. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47(2):246–54.

Johansson A, Johansson A, Unell L, Ekbäck G, Ordell S, Carlsson GE. Self-reported dry mouth in Swedish population samples aged 50, 65 and 75 years. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e107-15.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Paula Saavedra Nieves for her valuable participation in statistical analysis.

Funding

The data are based on a population-based survey sponsored by the Spanish Society of Gerodontology (SEGER). This study was partly funded by a pre-doctoral grant (on a competitive basis) from the Health Research Institute of Santiago de Compostela that was awarded to Alba Pérez Jardón (IDIS2020/PREDOC/03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B.C and M.P-S conceived the ideas; A.P.J., E.O.R, A.B.C, E.V.O and J.L.L designed the study; JM.M.G and M.P-S: methodology; A.P.J and M.M.P collected the data; A.B.C., M.P-S and J.L.L analysed the data; M.P-S.: software; A.P.J., J.L.L., E.O.R, and M.M.P writing—original draft preparation; M.P-S, A.B.C,, E.V.O, JM.M.G writing—review and editing; M.P-S.: supervision and project administration; A.P.J, M.P-S, M.M.P, E.O.R,, E.V.O, J.L.L, JM.M.G and A.B.C final approval of the version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela (REF USC-2020). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The survey was conducted over the phone and recorded so that the respondents voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. This consent procedure has been approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Santiago de Compostela.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Survey database.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Jardón, A., Pérez-Sayáns, M., Peñamaría-Mallón, M. et al. Xerostomia, the perception of general and oral health and health risk behaviours in people over 65 years of age. BMC Geriatr 22, 982 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03667-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03667-3