Abstract

Background

Diet and physical activity are key components of healthy aging. Current interventions that promote healthy eating and physical activity among the elderly have limitations and evidence of French interventions’ effectiveness is lacking. We aim to assess (i) the effectiveness of a combined diet/physical activity intervention (the “ALAPAGE” program) on older peoples’ eating behaviors, physical activity and fitness levels, quality of life, and feelings of loneliness; (ii) the intervention’s process and (iii) its cost effectiveness.

Methods

We performed a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial with two parallel arms (2:1 ratio) among people ≥60 years old who live at home in southeastern France. A cluster consists of 10 people participating in a “workshop” (i.e., a collective intervention conducted at a local organization). We aim to include 45 workshops randomized into two groups: the intervention group (including 30 workshops) in the ALAPAGE program; and the waiting-list control group (including 15 workshops). Participants (expected total sample size: 450) will be recruited through both local organizations’ usual practices and an innovative active recruitment strategy that targets hard-to-reach people. We developed the ALAPAGE program based on existing workshops, combining a participatory and a theory-based approach. It includes a 7-week period with weekly collective sessions supported by a dietician and/or an adapted physical activity professional, followed by a 12-week period of post-session activities without professional supervision. Primary outcomes are dietary diversity (calculated using two 24-hour diet recalls and one Food Frequency Questionnaire) and lower-limb muscle strength (assessed by the 30-second chair stand test from the Senior Fitness Test battery). Secondary outcomes include consumption frequencies of main food groups and water/hot drinks, other physical fitness measures, overall level of physical activity, quality of life, and feelings of loneliness. Outcomes are assessed before the intervention, at 6 weeks and 3 months later. The process evaluation assesses the fidelity, dose, and reach of the intervention as its causal mechanisms (quantitative and qualitative data).

Discussion

This study aims to improve healthy aging while limiting social inequalities. We developed and evaluated the ALAPAGE program in partnership with major healthy aging organizations, providing a unique opportunity to expand its reach.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05140330, December 1, 2021.

Protocol version: Version 3.0 (November 5, 2021).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Relevance

Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years old will increase from 12 to 22% (and from 25 to 34% in France) [1]. Older age is associated with a greater prevalence of chronic diseases, frailty, dependence, and associated healthcare costs [2,3,4]. This has led the United Nations General Assembly to declare 2021–2030 the “Decade of Healthy Ageing” which aims to optimize older peoples’ functional abilities (e.g., ability to meet one’s basic needs; to learn, grow, and make decisions; to build and maintain relationships; and to be mobile) [2]. The Decade of Health Ageing includes equity as one of its guiding principles, highlighting that some population groups may sometimes require more attention to ensure the greatest benefit to the least advantaged [5].

The World Health Organization identified nutrition and physical activity as key components that influence healthy ageing [6]. Healthy diets among the elderly may help to maintain autonomy and to increase activity limitation and limitation-free life expectancy: in particular, it has been associated with a reduced risk of physical frailty [7,8,9,10], activity limitation [11], decline in cognitive function, [12] and death [13]. Physical activity in older age also helps to maintain autonomy, reduces risks of diseases like coronary heart disease or diabetes, improves physical and mental health capacities, as well as quality of life and social outcomes (e.g., community involvement, maintenance of social networks) [6, 14]. Physical activity can especially help reduce social isolation and loneliness. These growing public health concerns have been made even more salient by the COVID-19 pandemic [15].

Several behavioral interventions promoting healthy eating among community-dwelling elderly people have been implemented worldwide. Most of them have included meal services and have targeted frail older people [16,17,18,19]. Other behavioral interventions that targeted broader populations of community-dwelling elderly people and included dietary educational interventions, found either no significant effect [20, 21] or positive impacts on diet, nutritional status and other outcomes like self-efficacy or social support [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Some of the effective interventions [22, 25, 26] originally aimed at improving dietary diversity among older people: eating a wide range of foods is positively associated with nutritional adequacy in diets and contributes to the prevention of frailty [28,29,30,31,32]. Many interventions which target older peoples’ physical activity levels have also been implemented, most frequently, to reduce the risk of falls [33]. These programs focused on improving posture, balance, and walking. Effective programs usually lasted 3 months (three times a week); however, some shorter programs (lasting five to eight weeks) were also found to improve balance and mobility issues [34,35,36]. The Australian Lifestyle-integrated Functional Exercise (LiFE) program, which combines both balance and strength training, merits particular interest. This program is an innovative intervention based on a new dual-tasking approach where exercises are included into the elderly’s usual daily activities in their everyday lives [37]. This program showed greater adherence than traditionally structured programs and had positive impacts on the risk of falls and the maintenance of functional capacities [37].

However, few studies have assessed the effectiveness of combined programs that target both dietary habits and physical activity among older adults who live at home (e.g., [25, 27]). These studies used traditional recruitment strategies and also did not make concerted efforts to recruit hard-to-reach older populations (e.g., those who live in deprived areas), who are known to participate infrequently in health promotion interventions [38]. Active recruitment strategies (i.e., direct, face-to-face contact) could be particularly effective in improving participation of hard-to-reach older people, but further evidence is needed [38, 39]. Finally, as part of the French national strategy for healthy aging [40], several national and regional stakeholders (e.g., the French Public Health Agency, regional health agencies, retirement funds, associations involved in health promotion) have been supporting health promotion interventions that target older peoples’ diet and physical activity for many years (most frequently as collective prevention workshops). However, no study to date has been conducted to assess their effectiveness [41].

Objectives

In this context, we designed the ALAPAGE study to assess:

-

(1)

the effectiveness of a combined diet and physical activity intervention (the “ALAPAGE program”) on older peoples’ dietary diversity and eating behaviors; physical activity and fitness; and quality of life and feelings of loneliness (effectiveness evaluation);

-

(2)

the fidelity, dose, and reach of the intervention as well as the mechanisms by which the intervention may modify outcomes (process evaluation);

-

(3)

the cost effectiveness of the intervention (economic evaluation).

The present article describes the ALAPAGE study protocol in conformance to SPIRIT’s (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) 2013 statement [42] (see completed SPIRIT checklist in Additional file 1).

Methods

Study design and setting

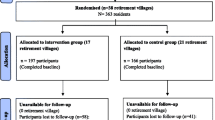

The ALAPAGE study is a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT) [43] with two parallel arms using a 2:1 ratio. It is performed among older people who live at home in southeastern France (intervention period: January 2022–October 2023). A cluster consists of approximately 10 people participating in a “workshop”, which is defined as a collective intervention that is conducted on the premises of local organizations (e.g., municipalities, social/community centers). A total of 45 workshops are randomized into two groups: (i) the intervention group (corresponding to 30 workshops), who benefits from the ALAPAGE program; and (ii) the control group (corresponding to 15 workshops), who will only benefit from the ALAPAGE program after the completion of the study (waiting-list control group).

The complete study duration for participants is four and a half months (19 weeks; see Fig. 1 for an overview of the study). Participants in the control group have measurement visits, but no intervention visits before benefiting from the ALAPAGE program.

The ALAPAGE study design was tested in a pilot study between September and February 2022 and was based on two intervention and one control workshops. This pilot study led us to make several modifications to the intervention (e.g., the increase of the sessions’ duration from 2 to 2.5 hours; the revision of the training content/duration that professionals undertook before the intervention; the improvements to the intervention tools), the data collection procedures (e.g., the addition/removal of items in self-administered questionnaires) and research documentation (e.g., the revision of the information sheets to make them more readable).

Participants and recruitment procedure

We aim to recruit 450 adults, age 60 years old or over who live at home, and split them across 45 workshops (30 intervention and 15 control workshops) with on average 10 participants in each (see details in paragraph “Sample size calculation”).

Selection of local organizations and allocation of workshops

First, we looked for local organizations who would volunteer to host the workshops as part of the ALAPAGE study. The research team, with support from its operational partners (e.g., the regional retirement fund) launched the call for applications to invite local organizations to participate in the study. Local organizations who were interested in the study filled out an information sheet (requesting information such as location, number of older people in their active file, experience in organizing prevention workshops, period of availability to organize one or more workshops, availability of a “point-of-contact” person to manage the logistical aspects of the workshops, the provision and storage of materials, etc.) and returned it to the research team. A total of 45 local organizations submitted proposals between June 1, 2021 and July 16, 2021. The research team and its operational partners then selected 25 out of the 45 organizations to host a total of 45 workshops. The selections were based on a reasoned choice and operational criteria (e.g., availability, materials, and staff resources).

We performed a block randomization with the use of computer-generated randomization lists. We created four time-based blocks (start date of the workshop); each observed a 2:1 allocation ratio. We did this to take into account the seasonality of both diet and physical activity behaviors in addition to any potential disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic (block 1: 12 workshops between January 2022–April 2022; block 2: 12 workshops between May 2022–October 2022; block 3: 15 workshops between November 2022–April 2023; block 4: 6 workshops between May 2023–June 2023).

Recruitment of participants

Participants are then recruited by one of two methods:

-

(1)

Recruited according to the usual practices of local organizations (e.g., announcements and advertisements within the organization, local newspapers, public posters, leaflets). The inclusion criteria are: age ≥ 60 years, who live at home, have health insurance coverage and are able to read and write in French. The non-inclusion criteria are: receiving allocation for dependence (i.e., belonging to one of the fourth-highest groups of the AGGIR grid, a six-level scale used in France to measure the independency levels of elderly people [44, 45]), being under guardianship, and having participated in a previous prevention workshop on diet or physical activity within the last 2 years. These criteria aim to target individuals: who, according to the operational partners’ usual practices within the field of healthy aging, are suitable for the preventive intervention program; who meet the research requirements (e.g., are able to give free and informed consent and to complete self-administered questionnaires) and who meet the regulatory requirements (health insurance).

-

(2)

Recruited using an active recruitment strategy, which was previously designed and pilot-tested by our research team, that targets hard-to-reach people [46]. In sum, this strategy aims to increase the participation of socioeconomically disadvantaged people and/or socially isolated older people in health-prevention programs on diet and physical activity by the following four steps: (i) identification in the retirement fund database of targeted older people; (ii) invitation letter by mail; (iii) telephone call by a social worker; (iv) home visit by the same social worker. The inclusion criteria are: 60–80 years old who live at home in the municipality where the prevention workshop will take place, receive allocation for economically deprived and/or socially isolated older people, have a telephone number recorded in the retirement fund database and be able to read and write in French. The non-inclusion criteria are the same as the aforementioned for people recruited by usual pathways. For each workshop of 10 participants, we aim to recruit 3 participants through this active strategy.

Staff from local organizations --for (1)--, or social workers --for (2)--, relay information about the study both orally and in writing and prescreen participants for eligibility criteria. During the inclusion session/visit (S0 and V0 for the intervention and control groups respectively, see Fig. 1), the dietician reads the written information aloud to the participants, verifies eligibility criteria and asks for informed consent in writing.

Interventions

Intervention group

The intervention (the ALAPAGE program that means “up to date” in French) was designed based on a diagnostic study that we performed in 2016–2017 to examine strengths, limitations, ways of improving existing prevention workshops on diet and physical activity for the elderly in France [41], and on the scientific literature. In particular, this diagnostic study highlighted the need to improve the attractiveness of these workshops to the elderly, the participation of socioeconomically-disadvantaged and socially-isolated people, and participation maintenance throughout the workshop sessions. We optimized the content of existing workshops by involving dieticians and APA professionals as part of the participation process, and used intervention mapping as a guide [47]. In sum, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior [48], the ALAPAGE program aims to improve participants’ attitudes, perceived norms, perceived self-control, and intention to improve diet and physical activity. Moreover, to increase the probability of behavior change and reduce the intention-behavior gap, we introduced additional behavior change techniques like setting goals, planning actions, using feedback and monitoring, and reviewing goals [49].

Each intervention workshop includes (i) a 7-week intervention period with weekly collective sessions supported by a dietician and/or a qualified APA professional (one introductory session, 4 sessions on diet, and 2 sessions on physical activity, each 2.5 hours in duration); followed by (ii) a 12-week intervention period that consists of a post-sessional program of activities among participants without the supervision of a professional (see Table 1 for more details). As part of this pragmatic trial, professionals (e.g., dieticians, APA professionals and staff from local organizations) have some flexibility in the implementation of the ALAPAGE program in order to take into account for “real-life” constraints (e.g., they can opt for a two-week interval between sessions instead of a one-week interval) [43]. Compared to existing workshops, the ALAPAGE program newly addresses the following themes: dietary diversity, nutritional profiles, budget (healthy eating on a budget), sustainable diet and, regarding physical activity, balance, flexibility, strength and aerobic exercises incorporated into everyday tasks [37], and a 10-minute routine exercise (see Table 1 for more details). The ALAPAGE program uses innovative tools developed as part of the participation process and involved dieticians, APA professionals, and elderly people.

Control group

Participants in the control group will receive no intervention and will only benefit from the ALAPAGE program at the end of the research study. In order to encourage retention, however, the inclusion visit (V0) includes light refreshments and the measurement visit (V2) includes an interesting one-hour activity on waste recycling (see details on the content of the control group measurement visits in Additional file 2).

Outcomes

Effectiveness evaluation

Primary and secondary outcomes, with few exceptions, are assessed before the intervention (“T0”), at 6 weeks (“T1” corresponding to the end of ALAPAGE program’s session period) and then 3 months later (“T2”) (see Table 2 for an overview of outcomes and data time points).

Primary outcomes

Dietary diversity is assessed using the Diversity ALAPAGE Score (DAS). Based on dietary diversity scores developed abroad [50,51,52], we developed the DAS using individuals’ consumption habits of 20 food categories (see Additional file 3 for more details). Individuals must complete two 24-hour diet recalls (for foods that they usually eat every day, such as fruits, vegetables, meat excluding poultry and sweetened products) and one Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (for foods that they consume less frequently, such as eggs, legumes, nuts, fatty fish, see Additional file 4). Each consumption earns positive or negative points according to the nutritional quality of its food category. The DAS for one individual is calculated by adding all attributed points. A higher DAS means a greater diversity in diet. We found that DAS was positively associated with the quality of diet among a representative sample of French people age 60 years or older [53], and that a low DAS was associated with an increased death risk among a cohort of older French people who were followed over 15 years [54].

Lower-limb muscle strength is assessed using the 30s Chair Stand Test from the Senior Fitness Test battery (adapted in French) [55]. Participants repeatedly stand up from and sit down on a chair for 30 seconds and an APA professional records the number of complete stands.

Secondary outcomes

Consumption frequencies of main food groups and water/hot drinks are assessed using data from two 24-hour diet recalls and one FFQ.

Physical fitness is assessed using the French version of the Senior Fitness Test battery [55]. Besides the 30s Chair Stand Test which indicates lower-body strength (see primary outcomes), it also includes: (i) the Arm Curl Test (upper-body strength); (ii) the 2-minute Step Test (aerobic endurance); (iii) the Chair Sit and Reach Test (lower-body flexibility); (iv) the Back Scratch Test (upper-body flexibility); and (v) the Get Up and Go Test (dynamic balance). Additionally, the Open-Eye Stand on Dominant Foot Test assesses static balance. According to the range of scores [56], there are four levels for each physical parameter: low, below average, to be maintained, and good.

Overall level of physical activity is assessed by (i) the number of steps recorded with a pedometer (Yamax Power-Walker EX™-210) during 1 week and reported by the participant on a weekly notebook provided by the APA professional; (ii) the Questionnaire d’activité physique pour personnes âgées (QAPPA) self-reported physical activity questionnaire for the elderly [57]. This 7-day recall questionnaire includes 4 items on moderate and intense physical activity. Scores are calculated using the number of minutes of each type of activity reported in metabolic equivalent per week and individuals are then classified into three activity levels (low, moderate, or high).

Quality of life is measured by the SF-12 V1 Health Survey questionnaire [58] which includes 12 questions corresponding to the following eight domains: 1) Limitations in physical activities because of health problems; 2) Limitations in social activities because of physical or emotional problems; 3) Limitations in usual role activities because of physical health problems; 4) Bodily pain; 5) General mental health; 6) Limitations in usual role activities because of emotional problems; 7) Vitality; and 8) General health perceptions.

Feelings of loneliness are assessed using one item of the environmental dimension of the FRAGIRE tool for assessing an older person’s risk for frailty [59]: “Do you feel lonely or abandoned?” (Not at all, A little, Quite a bit, A lot).

Process evaluation

Intervention fidelity, dose, and reach are assessed using data obtained from attendance lists, information sheets completed by local organizations, information sheets completed by dieticians and APA professionals after each session, and self-administered questionnaires that are completed by participants during T1 and T2 (e.g., self-reported exercises from everyday tasks; participation in post-session activities between participants, see Additional file 5) [60]. To ensure fidelity, and to make sure that the program is transferable, we will also document how the actors who are involved in the program interact [61], in comparison with planned interactions.

To explore how the intervention might modify outcomes, we will analyze data from the self-administered questionnaires to be completed by participants at T0, T1 and T2, especially from the questions that assess the major constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior [48] (beliefs, attitudes, and intention, see Additional file 5). In the Theory of Planned Behavior questionnaires, the behavior of interest must be clearly defined in terms of target, action, context, and time elements. We measured the beliefs, attitudes, and intention of physical activity (“daily physical activity in the next 3 months”) [62], but found that the questions were not applicable to dietary diversity. We also conduct semi-structured individual interviews with approximately 20 participants from the intervention group, who accepted to be contacted again, to gain a better understanding of how/why participation in ALAPAGE workshops improves (or does not improve) eating behaviors, physical activity, and quality of life, as facilitators and barriers to behavior changes that participants encountered.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation

All unit costs (e.g., hourly cost for dieticians, APA professionals) and quantities required (e.g., total number of working hours) were listed and collected in advance from the local organizations who are responsible for the intervention and control workshops. These costs will then be compared to the effectiveness of the intervention (outcomes related to eating behaviors, physical activity, and Quality Adjusted Life Years, QALYs [63]) using the cost-effectiveness ratio (i.e., incremental costs divided by the incremental health benefits) [64].

Sample characterization

Sociodemographic data (e.g., age, sex, educational level, perceived financial situation, frequency of participation in social activities) as antecedents towards physical activity and history of falls are also collected through self-questionnaires (see Additional file 6).

Data collection procedure

Data collection is performed on the premises of local organizations under the supervision of a dietician and/or an APA professional, except for: one 24-hour recall performed at home during week 5 for the control group and during week 18 for both groups; and the number of steps during 1 week recorded at home three times for each group (Table 2).

Face-to-face interviews with participants are performed by researchers, who have significant qualitative research experience, in the month following T2 at the local organization or at home depending on the participants’ preference.

All study participants will be financially compensated (the intervention group will receive a 15 € voucher; the control group will receive two 15 € vouchers, the second voucher compensating for the additional participation in the measurement visit).

Expected and non-expected serious adverse events and other unintended effects of the intervention (i.e., those that require hospitalization, result in a significant or long-lasting disease/disability, or death) are collected and immediately reported to the research team by the sessions’ dieticians and APA professionals.

Prior to the commencement of the study, dieticians and APA professionals participate in training sessions that are led by research team members (including by one person who is certified in Good Clinical Practices [GCP]) and includes (i) a two-hour video conference that presents the study and its data circuit; (ii) a half-day session on research issues (e.g., clinical practices, information, consent, notification of adverse events); and a further one and a half day session on the study’s content and visits (e.g., program, objectives, tools).

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculations are based on the (i) research team’s preliminary results on dietary diversity and the development of the DAS [53], and the research team’s consensus on the intervention’s effect size of + 1 standard deviation between T0 and T2; (ii) impact on older people’s lower-limb muscle strength from a previous intervention that showed similarities with the exercises proposed in the ALAPAGE program [65]. We performed power calculations using simulations (10,000 samples per simulation, see Additional file 7 for more details) assuming α = 0.05, similar characteristics of participants in both groups, a 30% dropout rate between T0 and T2, and an intra-cluster correlation of 0.03 [22, 66]. Based on these simulations, we intend to enroll 300 participants in the intervention group (i.e., 30 workshops with 10 participants in each) and 150 participants in the control group (15 workshops with 10 participants in each); this provides a 95% power for both primary outcomes.

Data management

The participants are each given a unique identification code (without any personal information that could allow for their identification). During the study period, all of the collected data is stored in a locked cabinet at the local organizations, according to a procedure compliant with GCP guidelines. When the study is complete, the collected data will be securely transmitted to the research team’s logistic department, who will create the databases. The collected data will be stored according to standards for archiving research materials.

Leaders of the research team who are involved in the ALAPAGE study and who have signed a consortium agreement will have access to the final study dataset.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses will be performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A α of 0.05 will be used to determine statistical significance.

First, descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, median, and frequency distribution) will be carried out to describe baseline characteristics (sociodemographic, life conditions, primary and secondary outcomes) of participants in both groups. To compare the baseline characteristics (age, gender, life conditions) between the two groups, a one-way ANOVA or a Kruskal-Wallis test will be used for continuous variables and a Chi-square or a Fisher’s exact test will be used for categorical variables.

As part of the effectiveness evaluation, linear or logistic (depending on the nature of the dependent variable) mixed models will be carried out to study the impact of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes, while taking into account the repeated nature of the data and the intra-cluster correlation. Time, group and their interaction will be defined as fixed factors (see Additional file 7 for more details). If imbalances occur between the groups, the baseline values will be added as covariates in the models. Missing data will be inspected, and, if appropriate, will be handled using multiple imputation.

As part of the process evaluation, we plan to perform mediation analyses to verify whether beliefs, attitudes, and intention are pathways by which the intervention impacts physical activity. Furthermore, we plan to perform moderating analyses to test whether the effect of the intervention varies according to some characteristics (in particular, type of recruitment, antecedents of physical activity or history of falls, and baseline dietary diversity).

As part of the process evaluation, qualitative data from participant interviews of the intervention group will be transcribed and analyzed using a data-driven inductive approach to explore how the intervention may have resulted in behavioral changes.

Dissemination policy

The results of the study will be communicated by the research team to the local organizations who participated in the study, the professional sponsors who are involved in healthy ageing and also the public (e.g., via the websites of the retirement fund and other operational partners). The study will result in several publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Discussion

The ALAPAGE study is a pragmatic cRCT which aims at assessing the effectiveness, process, and cost effectiveness of a combined diet and physical activity collective intervention among older French people who live at home. It is conducted by a multidisciplinary research team (epidemiology/public health, human nutrition, physical activity, health economics, social psychology) in close partnership with experienced operational partners in health promotion among elders.

This study has several strengths. First, the ALAPAGE program on diet and physical activity evaluated in this study is based on “real-life” interventions, i.e., collective prevention workshops that have been implemented by our operational partners for many years. Based on a diagnostic study, we optimized these workshops and tools using both a participatory approach involving dieticians, APA professionals and elderly people, and a theory-based approach [48, 49]. This development process is recommended to enhance the interventions’ fidelity, suitability to context, and effectiveness [67]. Secondly, this study includes an innovative active recruitment strategy to improve participation of hard-to-reach (i.e., socioeconomically-disadvantaged and socially-isolated) older people. It will thus contribute to creating greater equity in healthy ageing [5] and help prove the effectiveness of strategies aimed at identifying socially isolated/lonely people and also connect them to services [15]. Third, this cRCT includes a wide range of outcomes relating to eating behaviors, physical activity and fitness but also to social aspects like quality of life and feelings of loneliness. The methodology will also allow us to explore the causal mechanisms of the intervention and to understand how the ALAPAGE program – if effective, as we hypothesize -- improves the behaviors of participants [67].

We must also acknowledge some limitations. First, the recruitment of participants will take place after the randomization of workshops. This may lead to recruitment bias and a discrepancy in the characteristics of the participants in both the intervention and the control groups [68]. As part of this pragmatic cRCT, our operational partners did not find it feasible to recruit participants before the cluster randomization or by means of a blinded and independent person. To limit recruitment bias (e.g., participants in the intervention group are more interested in diet and physical activity issues and are thus more likely to change their behaviors than those in the control group), we will use a waiting-list control group design. Consequently, all participants are interested in participating in workshops on diet and physical activity. Second, due to feasibility constraints, the times points differ slightly between the intervention and control groups for some of the outcomes. However, we have done our best to limit these differences and to reconcile methodology requirements and practical feasibility. We hypothesize that this will have a limited impact on our results. Lastly, we cannot exclude differing attrition rates between the intervention and control groups that may lead to biased estimates of the intervention’s effects. In this instance, we plan to use appropriate econometric techniques (e.g., a Heckman sample selection correction model [69]) to correct for attrition bias [70].

The results of this study should help to implement public health interventions that are effective at improving dietary diversity, physical activity and fitness, and social outcomes among older people who live at home. They will contribute to the improvement of healthy aging while limiting social inequalities. The ALAPAGE program has been developed and will be evaluated in close relationship with major operational partners of healthy aging in France, thus providing a unique opportunity to expand its reach.

Roles and responsibilities

The steering committee for the ALAPAGE study is comprised of the study’s scientific coordinator, the principal investigator (and representative of the study’s sponsor) and several of his team members who are responsible for the project’s management, representatives from operational partners (Carsat Sud-Est, ASEPT PACA, Mutualité Française Sud, Géront’ONord, SudEval and Trophis), and a number of representatives from the scientific committee. The steering committee meets regularly depending on the research’s needs, including reviewing the study’s progress and providing overall feedback to each of its members. It is also responsible for making any important decisions regarding the proper conduct of the study and compliance with the protocol. It verifies ethical compliance.

Finally, a scientific committee composed of experts in health psychology, nutritional epidemiology, adapted physical activity and health economics meet at least once a year (or more times if necessary) to validate methodological aspects of the study, provide guidance on the study’s conduct and the dissemination of results.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- APA:

-

Adapted physical activity

- cRCT:

-

cluster randomized controlled trials

- DAS:

-

Diversity ALAPAGE Score

- FFQ:

-

Food Frequency Questionnaire

- GCP:

-

Good Clinical Practices

- LiFE:

-

Lifestyle-integrated Functional Exercise program

- QALYs:

-

Quality Adjusted Life Years

References

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2019. 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed 31 Mar 2022.

World Health Organization. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Chang AY, Skirbekk VF, Tyrovolas S, Kassebaum NJ, Dieleman JL. Measuring population ageing: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e159–67.

Roussel R. Personnes âgées dépendantes : les dépenses de prise en charge pourraient doubler en part de PIB d’ici à 2060. Etudes et Résultats (DREES). 2017;1032:1–6.

World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy ageing plan of action. 2020.

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Struijk EA, Hagan KA, Fung TT, Hu FB, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E. Diet quality and risk of frailty among older women in the nurses’ health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:877–83.

Otsuka R, Tange C, Tomida M, Nishita Y, Kato Y, Yuki A, et al. Dietary factors associated with the development of physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23:89–95.

Pilleron S, Ajana S, Jutand M-A, Helmer C, Dartigues J-F, Samieri C, et al. Dietary patterns and 12-year risk of frailty: results from the Three-City Bordeaux study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:169–75.

Rahi B, Ajana S, Tabue-Teguo M, Dartigues J-F, Peres K, Feart C. High adherence to a Mediterranean diet and lower risk of frailty among French older adults community-dwellers: results from the Three-City-Bordeaux study. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1293–8.

Pilleron S, Pérès K, Jutand M-A, Helmer C, Dartigues J-F, Samieri C, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of self-reported activity limitation in older adults from the Three-City Bordeaux study. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:549–56.

Otsuka R, Nishita Y, Tange C, Tomida M, Kato Y, Nakamoto M, et al. Dietary diversity decreases the risk of cognitive decline among Japanese older adults: dietary diversity and cognitive decline. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:937–44.

Oftedal S, Holliday EG, Attia J, Brown WJ, Collins CE, Ewald B, et al. Daily steps and diet, but not sleep, are related to mortality in older Australians. J Sci Med Sport. 2020;23:276–82.

Marquez DX, Aguiñaga S, Vásquez PM, Conroy DE, Erickson KI, Hillman C, et al. A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1098–109.

World Health Organization. Social isolation and loneliness among older people: advocacy brief. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Zhou X, Perez-Cueto FJA, Santos QD, Monteleone E, Giboreau A, Appleton KM, et al. A systematic review of Behavioural interventions promoting healthy eating among older people. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):128.

Buhl SF, Beck AM, Christensen B, Caserotti P. Effects of high-protein diet combined with exercise to counteract frailty in pre-frail and frail community-dwelling older adults: study protocol for a three-arm randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:637.

Dorhout BG, Haveman-Nies A, van Dongen EJI, Wezenbeek NLW, Doets EL, Bulten A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a diet and resistance exercise intervention in community-dwelling older adults: ProMuscle in practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:792–802.e2.

van Dongen EJI, Haveman-Nies A, Doets EL, Dorhout BG, de Groot LCPGM. Effectiveness of a diet and resistance exercise intervention on muscle health in older adults: ProMuscle in practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1065–1072.e3.

Lara J, Turbett E, Mckevic A, Rudgard K, Hearth H, Mathers JC. The Mediterranean diet among British older adults: its understanding, acceptability and the feasibility of a randomised brief intervention with two levels of dietary advice. Maturitas. 2015;82:387–93.

Gallois KM, Buck C, Dreas JA, Hassel H, Zeeb H. Evaluation of an intervention using a self-regulatory counselling aid: pre- and post- intervention results of the OPTIMAHL 60plus study. Int J Public Health. 2013;58:449–58.

Kimura M, Moriyasu A, Kumagai S, Furuna T, Akita S, Kimura S, et al. Community-based intervention to improve dietary habits and promote physical activity among older adults: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:8.

Salehi L, Mohammad K, Montazeri A. Fruit and vegetables intake among elderly Iranians: a theory-based interventional study using the five-a-day program. Nutr J. 2011;10:123.

Yates BC, Pullen CH, Santo JB, Boeckner L, Hageman PA, Dizona PJ, et al. The influence of cognitive-perceptual variables on patterns of change over time in rural midlife and older women’s healthy eating. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:659–67.

Uemura K, Yamada M, Okamoto H. Effects of active learning on health literacy and behavior in older adults: a randomized controlled trial: health education to enhance health literacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1721–9.

Murayama H, Taguchi A, Spencer MS, Yamaguchi T. Efficacy of a community health worker–based intervention in improving dietary habits among community-dwelling older people: a controlled, crossover trial in Japan. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47:47–56.

Smith ML, Lee S, Towne SD, Han G, Quinn C, Peña-Purcell NC, et al. Impact of a behavioral intervention on diet, eating patterns, self-efficacy, and social support. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52:180–6.

Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop M-C. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Rome: FAO; 2011.

Tsuji T, Yamamoto K, Yamasaki K, Hayashi F, Momoki C, Yasui Y, et al. Lower dietary variety is a relevant factor for malnutrition in older Japanese home-care recipients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:197.

Roberts SB, Hajduk CL, Howarth NC, Russell R, McCrory MA. Dietary variety predicts low body mass Indexand inadequate macronutrient and MicronutrientIntakes in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:613–21.

Motokawa K, Watanabe Y, Edahiro A, Shirobe M, Murakami M, Kera T, et al. Frailty severity and dietary variety in Japanese older persons: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:451–6.

Marshall TA, Stumbo PJ, Warren JJ, Xie X-J. Inadequate nutrient intakes are common and are associated with low diet variety in rural, Community-Dwelling Elderly. J Nutr. 2001;131:2192–6.

Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C. Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004963.

Avelar NCP, Bastone AC, Alcântara MA, Gomes WF. Effectiveness of aquatic and non-aquatic lower limb muscle endurance training in the static and dynamic balance of elderly people. Rev Bras Fis. 2010;14:229–36.

Chulvi-Medrano I, Colado JC, Pablos C, Naclerio F, García-Massó X. A lower-limb training program to improve balance in healthy elderly women using the T-bow device. Phys Sportsmed. 2009;37:127–35.

Sherrington C, Pamphlett PI, Jacka JA, Olivetti LM, Nugent JA, Hall JM, et al. Group exercise can improve participants’ mobility in an outpatient rehabilitation setting: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:493–502.

Clemson L, Fiatarone Singh MA, Bundy A, Cumming RG, Manollaras K, O’Loughlin P, et al. Integration of balance and strength training into daily life activity to reduce rate of falls in older people (the LiFE study): randomised parallel trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e4547.

Liljas AEM, Walters K, Jovicic A, Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, Goodman C, et al. Strategies to improve engagement of ‘hard to reach’ older people in research on health promotion: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:349.

Katula JA, Kritchevsky SB, Guralnik JM, Glynn NW, Pruitt L, Wallace K, et al. Lifestyle interventions and Independence for elders pilot study: recruitment and baseline characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:674–83.

Ministère des solidarités et de la santé. Vieillir en bonne santé. Une stratégie globale pour prévenir la perte d’autonomie. 2020-2022. Dossier de presse. 2020.

Bocquier A, Dubois C, Gazan R, Pérignon M, Amiot-Carlin MJ, Darmon N. L’offre de prévention « nutrition senior » : une étude quantitative et qualitative exploratoire dans le cadre de la préparation d’une recherche interventionnelle en région (projet ALAPAGE). 2017. 5ème Congrès Francophone Fragilité du sujet âgé & Prévention de la perte d’autonomie, Paris, France, 16–17 mars 2017.

Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586.

Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147.

Dupourqué E, Schoonveld S, Bushey JB. AGGIR, the Work of Grids. Long-term care news. 2012;32:1–11.

Negrete Ramírez JM, Roose P, Dalmau M, Cardinale Y, Silva E. A DSL-based approach for detecting activities of daily living by means of the AGGIR variables. Sensors. 2021;21:5674.

Bocquier A, Dubois C, Verger P, Darmon N. INVITE study group. Improving participation of hard-to-reach older people in diet interventions: the INVITE strategy. Eur J Pub Health. 2019;29 Supplement_4:ckz186.474.

Jacquemot AF, Bocquier A, Dubois C, Vinet-Jullian A, Cousson-Gélie F, Darmon N. Co-construction et fondements théoriques d’ateliers de prévention sur l’alimentation et l’activité physique à destination des seniors pour le projet ALAPAGE. Nutr Clin Métabol. 2021;35:73–4.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Verger EO, Le Port A, Borderon A, Bourbon G, Moursi M, Savy M, et al. Dietary diversity indicators and their associations with dietary adequacy and health outcomes: a systematic scoping review. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1659–72.

Vadiveloo M, Dixon LB, Mijanovich T, Elbel B, Parekh N. Development and evaluation of the US healthy food diversity index. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1562–74.

Drescher LS, Thiele S, Mensink GBM. A new index to measure healthy food diversity better reflects a healthy diet than traditional measures. J Nutr. 2007;137:647–51.

Prat R, Gazan R, Jacquemot AF, Dubois C, Féart C, Darmon N, et al. Evaluation de la validité du score de diversité ALAPAGE avec des indicateurs de qualité nutritionnelle de l’alimentation de seniors en France (INCA3). Journées Francophones de Nutrition, Lille, France, 10–12 novembre 2021.

Voix C, Gazan R, Dubois C, Helmer C, Delcourt C, Verger E, et al. Diversité alimentaire et risque de décès en population générale âgée. Journées Francophones de Nutrition, Lille, France, 10–12 novembre 2021.

Fournier J, Vuillemin A, Le Cren F. Measuring physical fitness in the elderly. Assessment of physical fitness in elderly: French adaptation of the “Senior Fitness Test”. Sci Sports. 2012;27:254–9.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60-94. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:162–81.

de Souto BP. Construct and convergent validity and repeatability of the questionnaire d’Activité physique pour les Personnes Âgées (QAPPA), a physical activity questionnaire for the elderly. Public Health. 2013;127:844–53.

Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1171–8.

Vernerey D, Anota A, Vandel P, Paget-Bailly S, Dion M, Bailly V, et al. Development and validation of the FRAGIRE tool for assessment an older person’s risk for frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:187.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258.

Savy M, Briaux J, Seye M, Douti MP, Perrotin G, Martin-Prevel Y. Tailoring process and impact evaluation of a “cash-plus” program: the value of using a participatory program impact pathway analysis. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(7):nzaa099.

González ST, López MCN, Marcos YQ, Rodríguez-Marín J. Development and validation of the theory of planned behavior questionnaire in physical activity. Span J Psychol. 2012;15:801–16.

Makai P, Brouwer WBF, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk EA, Nieboer AP. Quality of life instruments for economic evaluations in health and social care for older people: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:83–93.

Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC. Does preventive care save money? Health economics and the presidential candidates. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:661–3.

Leirós-Rodríguez R, Soto-Rodríguez A, Pérez-Ribao I, García-Soidán JL. Comparisons of the health benefits of strength training, aqua-fitness, and aerobic exercise for the elderly. Rehabil Res Pract. 2018;2018:1–8.

Giraudeau B. The cluster-randomized trial. Méd Sci. 2004;20:363–6.

Bleijenberg N, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Trappenburg JCA, Ettema RGA, Sino CG, Heim N, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: enriching the development phase of the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:86–93.

Caille A, Kerry S, Tavernier E, Leyrat C, Eldridge S, Giraudeau B. Timeline cluster: a graphical tool to identify risk of bias in cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2016;354:i4291.

Roux P, Le Gall J-M, Debrus M, Protopopescu C, Ndiaye K, Demoulin B, et al. Innovative community-based educational face-to-face intervention to reduce HIV, hepatitis C virus and other blood-borne infectious risks in difficult-to-reach people who inject drugs: results from the ANRS-AERLI intervention study: educational intervention for PWID. Addiction. 2016;111:94–106.

Molina Millan T, Macours K. Attrition in randomized control trials: using tracking information to correct Bias. 2017. https://ftp.iza.org/dp10711.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the dieticians and adapted physical activity professionals, who contributed to the design of the ALAPAGE program (as part of the participation process); the staff from local organizations who volunteered to participate in the ALAPAGE study; the professionals and older people who accepted to participate in the trial’s pilot study; the social workers and the management team from SudEval (the partner responsible for the recruitment of hard-to-reach older people); as well as all of the members of the steering and scientific committees.

The authors also thanks Mathieu Bertrand, Elisa Monticelli, Romain Paisant, Rosalie Prat, Julienne Sarthou, and Cindy Voix who contributed to the development of the ALAPAGE Study during their internship.

†The ALAPAGE Study Group includes the authors of the present manuscript and: Valérie Arquier10, Guillaume Briclot10, Rachel Chamla11, Florence Cousson-Gélie12,13, Sarah Danthony8, Karin Delrieu14, Julie Dessirier14, Catherine Féart3, Christine Fusinati11, Rozenn Gazan15, Mélissa Gibert16, Valérie Lamiraud14, Matthieu Maillot15, Dolorès Nadal16, Christelle Trotta10, Eric O. Verger9, Valérie Viriot17.

10 Caisse d’assurance retraite et de la santé au travail Sud-Est (Carsat Sud-Est), Marseille, France.

11 Association Géront’ONord Pôle Infos Séniors Marseille Nord, Marseille, France.

12 Institut régional du Cancer Montpellier/Val d’Aurelle, Epidaure, Montpellier, France.

13 Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, Univ. Montpellier, EPSYLON, Montpellier, EA, France.

14 Mutualité Française Sud Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Marseille, France.

15 MS-Nutrition, Marseille, France.

16 SudEval Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Corse, Marseille, France.

17 Association de Santé, d’Éducation et de Prévention sur les Territoires Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (ASEPT PACA), Marseille, France.

Funding

The ALAPAGE study is funded by the French Institute for Public Health Research (IReSP) as part of the general call for proposals 2018 (project LI-DARMONAAP18-PREV-004), the Regional Health Agency Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (ARS PACA), the southeastern France retirement fund (Carsat Sud-Est) and the Région Sud - Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur.

The IReSP, the ARS PACA and the Région Sud - Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur have no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. The Carsat Sud-Est is part of the steering committee for the study, and took part to the design of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AB wrote the research proposal that was sent to the funding organization and designed the study with AFJ, CD, HT, CC, GM, AV, PV, and ND, and drafted the first version of the manuscript with ND. AFJ designed the study with AB, CD, HT, CC, GM, AV, PV, and ND, and implemented the pilot study with CD, HT, CC, GM, AV, PV, and ND. CD designed the study with AFJ, HT, CC, GM, AV, PV, and ND, coordinated the design of the ALAPAGE program’s diet sessions, and implemented the pilot study with AFJ, HT, CC, GM, AV, PV, and ND. HT, CC and GM designed the study with AB, AFJ, CD, AV, PV, and ND, and implemented the pilot study with AFJ, CD, AV, PV, and ND. SC and LF managed the statistical aspects of the project. BDC managed the cost-effectiveness aspects of the project. AV designed the study with AB, AFJ, CD, HT, CC, PV, and ND, coordinated the design of the ALAPAGE program’s physical activity sessions, and implemented the pilot study with AFJ, CD, HT, CC, PV, and ND. PV serves as the study’s principal investigator (PI), designed the study with AB, AFJ, CD, HT, CC, AV, and ND, implemented the pilot study with AFJ, CD, HT, CC, AV, and ND and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. ND designed the study with AB, AFJ, CD, HT, CC, AV, and PV, supervised the design of the ALAPAGE program, implemented the pilot study with AFJ, CD, HT, CC, AV, PV, and ND, and drafted the first version of the manuscript with AB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the French ethics committee “Comité de Protection des Personnes TOURS - Région Centre - Ouest 1” (FDA IRB n°IORG0008143) on March 30, 2021 (n° 2021 T2–06). Major changes to this study protocol will be communicated to the ethics committee for approval.

Written consent to participate will be obtained after the dietician has provided all necessary information about the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

SPIRIT 2013 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Control group measurement visits’ content.

Additional file 3.

Diversity ALAPAGE Score: calculation method.

Additional file 4.

Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

Additional file 5.

Self-administered questionnaires’ sections related to process evaluation.

Additional file 6.

Self-administered questionnaires’ section related to participant’s characteristics.

Additional file 7.

Sample size calculation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bocquier, A., Jacquemot, AF., Dubois, C. et al. Study protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial to improve dietary diversity and physical fitness among older people who live at home (the “ALAPAGE study”). BMC Geriatr 22, 643 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03260-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03260-8