Abstract

Background

To explore whether differences between men and women in the sensitivity to (strength of the association) and/or in the exposure to determinants (prevalence) contribute to the difference in physical functioning, with women reporting more limitations.

Methods

Data of the Doetinchem Cohort Study was used (n = 5856, initial ages 26–70 years), with follow-up measurements every 5 years (up to 20). Physical functioning (subscale SF-36, range:0–100), sex (men or women) and a number of socio-demographic, lifestyle- and health-related determinants were assessed. Mixed-model multivariable analysis was used to investigate differences between men and women in sensitivity (interaction term with sex) and in exposure (change of the sex difference when adjusting) to determinants of physical functioning.

Results

The physical functioning score among women was 6.55 (95%CI:5.48,7.61) points lower than among men. In general, men and women had similar determinants, but pain was more strongly associated with physical functioning (higher sensitivity), and also more prevalent among women (higher exposure). The higher exposure to low educational level and not having a paid job also contributed to the lower physical functioning score among women. In contrast, current smoking, mental health problems and a low educational level were more strongly associated with a lower physical functioning score among men and lower physical activity and higher BMI were more prevalent among men.

Conclusions

Although important for physical functioning among both men and women, our findings provide no indications for reducing the difference in physical functioning by promoting a healthy lifestyle but stress the importance of differences in pain, work and education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical functioning involves the ability of performing daily physical and routine activities. Self-reported data of physical functioning are commonly used for health and ageing research and one common finding is that women more often report limitations in performing these routine activities compared to men [1,2,3,4]. Insights into why men and women differ in physical functioning may provide relevant information for the prevention of physical limitations and the promotion of healthy ageing. One approach to study the difference in physical functioning between men and women is to examine differences in (modifiable) determinants for poorer physical functioning. Men and women may differ in the sensitivity to determinants; the strength of the association with physical functioning differs. Another possibility is that men and women may differ in their exposure to determinants, i.e. the prevalence of determinants differs.

Potential (modifiable) determinants for physical functioning among older adults are socio-demographic, lifestyle-related or health-related [2, 3, 5]. A difference between men and women in the sensitivity to these determinants are often not reported in the literature, but a difference in the prevalence (i.e. exposure) are more commonly known. Socio-demographic factors such as a low level of education, not having a paid job or a low level of social contacts are mentioned as determinants for poorer physical functioning [2, 3, 5], with women on average having a lower level of education [6], more often being unemployed [6] and having more social contacts [7]. Lifestyle related determinants for poorer physical functioning are smoking, physical inactivity, no alcohol consumption compared to moderate consumption and both over- and underweight [2, 3, 5]. For some of these determinants it is known that men and women in western societies differ in exposure, this holds e.g. for smoking (higher among men [8]), alcohol consumption (higher among men [9]), and overweight/obesity (higher among middle-aged men [10]). In addition, many health conditions can be viewed as determinants for poorer physical functioning including all chronic diseases and pain. For a long time it has been described that women are more likely to experience health conditions associated with high morbidity (including worse physical functioning) and low mortality, whereas men are more likely to experience conditions associated with high mortality [11]. Women have a higher life expectancy and a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions [12], with for instance pain more often found among women [13]. So, differences between men and women in exposure to determinants are thus known or to be expected. These are however usually not taken into account while studying determinants for poor physical functioning.

Taken together, the investigation of the difference between men and women in physical functioning is limited, especially using a systematic approach across a wide range of determinants. Therefore, in order to provide insight into how differences between men and women in sensitivity and/or exposure to (modifiable) determinants contribute to the more reported limitations in physical functioning among women compared to men, data from a Dutch cohort study were examined with 20 years of follow-up, representing a population aging from 26–70 to 46–87 years.

Methods

Study sample

Data from the Doetinchem Cohort Study were used, a Dutch prospective population-based study [14]. The first cycle (years: 1987–1991) was carried out among 12,406 men and women aged 20–59 years from Doetinchem. A random sample of these respondents (n = 7769) was re-invited every five years. Measurements included questionnaires and a physical examination. The study was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments since 1964, and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO). All participants gave written informed consent. Physical functioning was measured from 1995 onwards, so the baseline measurement of the study sample was set in the years 1995–1999, with a maximum of four follow-up measurements (supplementary Fig. 1). Participants were included in the current study if they had a physical functioning score and determinant value on at least one measurement point, resulting in 5856 participants (of the 6391), aged 26–70 years at baseline, with on average 2.8 follow-up measurements in the final multivariable model (total number of observations = 16,773).

Measures

Physical functioning was measured using the physical functioning scale of the Dutch version of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [15, 16], which contains responses on the question ‘The following items are about activities you might do during a typical day. Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much?' for the following 10 items: Vigorous activities such as running, lifting heavy objects or participating in strenuous sports; Moderate activities such as moving a table, vacuuming or bicycling; lifting or carrying groceries; climbing several flights of stairs; climbing one flight of stairs; bending, kneeling, or stooping; walking more than a thousand meter; walking 500 m; Walking 100 m and bathing or dressing yourself. The response options were: “yes, limited a lot”/”yes, limited a little”/”no, not limited at all”. The sum scores were rescaled to a score from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better physical functioning [16].

Possible determinants included sociodemographic and lifestyle- and health-related characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics included sex (sex registered at civil registers, i.e. defined at birth), age (years), work status (yes/no), living alone (yes/no) and level of education (defined as the highest level of education obtained). Educational level was categorized into low (intermediate secondary education or less), moderate (intermediate vocational or higher secondary education), and high (higher vocational education or university). Lifestyle characteristics included current smoking status (yes/no), alcohol consumption (total number of glasses alcohol per day, categorized into ≤ 1 glass/day and > 1 glass/day), physical activity (assessed with a self-administered questionnaire on time spent on physical activities, defined as total hours/week including light, moderate or vigorous leisure time physical activities, sleep duration (average per 24 h, and classified in short (≤ 6 h/night), normal (7–8 h/night) and long (≥ 9 h/night) [17]) and BMI (Body Mass Index), calculated by weight(kg)/height(m)^2 from measured height and body weight (with classification following WHO guidelines [10]). Health-related characteristics included self-reported chronic conditions, pain and mental health. The number of chronic conditions was based on the following diseases: stroke, heart attack, diabetes, cancer, and chronic low back pain. Pain was based on the question “How much bodily pain have you had during the past 4 weeks?” part of the SF-36 questionnaire with response options “none”, “very mild”, “mild”, “moderate”, “severe” and “very severe” [16]. “Very mild” and “mild” were combined as mild pain, and the higher categories in ‘moderate to severe’. Mental health was measured using the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) and dichotomized into ‘poor’ (≤ 60) versus ‘good’ (> 60) mental health [18].

Data analyses

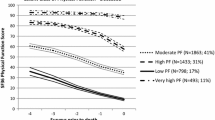

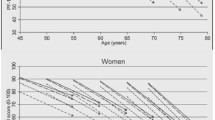

Multivariable mixed model analyses for repeated measures was used, including sociodemographic, lifestyle and health-related determinants. A tobit model in the likelihood function was used to correct for the maximum threshold of 100 of the SF-36 physical functioning score that is accompanied with a ceiling effect [19, 20]. The model with the best fit to depict the difference between men and women in physical functioning by age also included age2. Multicollinearity among determinants was tested and not found (all variance inflation factors < 10 and correlation < 0.5). In order to evaluate the differences between men and women in sensitivity we examined the interaction term determinant*sex separately for each determinant in a multivariable model including all determinants. A p < 0.10 belonging to this interaction beta was considered as a statistical significant difference in sensitivity, i.e. the association between the determinant and physical functioning [21]. Each multivariable association between the determinant and physical functioning was investigate for men and women separately. In order to evaluate the difference between men and women in exposure we determined the percentage change of the beta sex in physical functioning by adjustment for the determinant of interest [22]. A relevant percentage change was set at > 5%. Because our data presents a wide age range we also explored whether the findings were different for those under and over 55 years of age at baseline. This statistical cut-off was chosen to create similar groups with regard to size and number of repeated measurements and to define the age after which the difference in physical functioning between men and women increases (Fig. 1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

There were 5856 participants with at least one measurements of physical functioning; 2762 men and 3094 women Table 1. At baseline, participants were between 26 and 70 years old. The age-unadjusted mean of the physical functioning score was higher for men (89.5) than women (86.0). Compared to men, women had on average a lower level of education, higher level of physical activity, were less often employed, reported more pain—both ‘mild’ and ‘moderate to severe’- and a lower score on mental health. In addition, alcohol consumption (> 1 glass/day) and overweight were more often found among men.

Sex difference in physical functioning by age

Physical functioning decreased with increasing age for both men and women Fig. 1 and Table 2. Adjusted for age, women scored on average 6.55 (95%CI:5.48,7.61) points lower than men (on a scale from 0 to 100) (Table 2). The sex difference is shown at all ages, though the gap seems to widen at older ages, from on average of 6 points at age 45 to 12 points at age 80. Both the linear (Beta = -0.54) and quadratic (Beta = -0.01) change in the sex difference were statistically significant, (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Differences between men and women in sensitivity

For both men and women, chronic diseases and pain were the strongest determinants associated with physical functioning Table 3. There was a difference in sensitivity between men and women – looking at the interaction terms of determinant*sex and comparing the associations for men and women separately – to current smoking, pain, mental health problems and educational level (p < 0.10). Mild pain had a larger negative association with physical functioning among women, and current smoking, a low educational level and mental health problems had a larger negative association with physical functioning among men. To illustrate: Mild versus no pain was associated with a lower physical functioning score of 10.9 points (95%CI:11.8,9.87) in women and of 9.30 points (95%CI:10.2,8.36) in men.

The differences between men and women in sensitivity were in general similar for adults above and below 55 years of age (data not shown). Exceptions were: a higher sensitivity to pain among women and to mental health problems among men were only significant among older adults, the sex-specific role of education was more pronounced among those < 55 years at baseline and the sex-specific role of work was only significant among adults aged < 55 years.

Differences between men and women in exposure

The largest effect of a difference between men and women in exposure was found for pain: a larger sex difference was observed in the multivariable model including the determinant pain (-5.41, 95%CI: -6.41,-4.42) compared to the model without pain (-3.28, 95%CI:-4.13,-2.43) Table 4. So, adjusting for pain decreased the sex difference by (2.13/3.28) 65.0%, therefore pain contributes to the more reported limitations in physical functioning among women. In addition, women more often had a low educational level, no paid job and were alcohol abstainers, each decreasing around 10% of the beta for the sex difference in physical functioning and therefore contributing. In contrast, men were on average more exposed to a higher BMI and lower levels of physical activity compared to women, contributing to more reported limitations in physical functioning among men and therefore suppressing the sex difference.

The differences between men and women in exposure were in general similar between adults above and below 55 years of age (data not shown). There were some differences in the relative size of contribution: work status contributed more among adults below versus above 55 years of age, whereas BMI suppressed more among those below 55 years. In exception, alcohol consumption only contributed to the sex difference among adults below 55 years.

Discussion

To summarize, our findings confirm that women report a poorer physical functioning compared to men (6.55 lower on average). This is similar to an older Finish population (mean age 61 years), where a mean difference of 6.67 points in the physical functioning score between men and women was found [23]. Other studies that use different measures to evaluate self-reported physical functioning (mainly ADL-focused measures) also show that women systematic report more limitations in physical functioning compared to men [1,2,3,4]. In addition, our results show that men and women have similar determinants of physical functioning. In exception, older women have a higher sensitivity to pain while men have a higher sensitivity to current smoking, a low educational level and mental health problems in association with physical functioning. Men and women more often differed in their exposure to determinants of poor physical functioning, where men were on average more exposed to a higher BMI and lower levels of physical activity, while women were higher exposed to pain, low alcohol consumption, lower educational level and no paid work, contributing to the more reported limitations in physical functioning among women.

Pain is the most important contributing determinant due to both a higher sensitivity and a higher exposure among (older) women compared to men. The association between pain and physical functioning has been found previously and determinants for pain seem to be quite similar to determinants associated with physical functioning [24]. In line with the current findings, pain is well-known to be more prevalent and more severe among women compared to men [13]. The type or origin of pain has not been measured in our study and can therefore not be disentangled, however, the contributing role of a higher exposure to pain does not differ between adult women or older women, suggesting a limited role of menstrual pain. The mechanisms underlying the association between pain and physical functioning are not fully understood [25]. Future studies on the link between pain and physical functioning should take differences between men and women into account to better understand the role of sex and/or gender in this association.

The current results suggest that tackling the health-related determinant pain may result in the reduction of the difference between older men and women in physical functioning. One study on the effect of a multimodal pain management program on pain-related physical disabilities in daily life suggested that older women (aged 40–60 years) improved more compared to men [26]. Preventing pain is, however, not an easy task, nor is pain management. Previous studies indicate that there are sex and gender differences in essential elements of pain treatment, suggesting the need for a specific approach for men and women. For example women use social support to cope with pain, while men seek behavior distraction [27]. To date, however, a men and women specific approach for pain treatment and management is often lacking. Besides pain also ‘poor mental health’ is a health issue associated with physical functioning, but in contrast to pain the association is stronger among men compared to women. Because men seem to be more sensitive to poor mental health, this does not contribute to the difference in physical functioning with more limitations among women, but it does emphasize the relevance of a specific approach for men and women. No earlier studies on the specific association for men and women between mental health and physical functioning were found.

This exploration on differences between men and women in sensitivity or exposure to determinants of self-reported physical functioning provides almost no clues for reducing the sex difference in physical functioning by a prevention strategy directed to modifiable lifestyle-related determinants. Though physical functioning in general may benefit from a healthier lifestyle, this might not reduce the more reported limitations in physical functioning among women compared to men. The prevalence of lifestyle-related determinants, in particular a higher BMI, is higher among middle aged men. A higher BMI is associated with a greater physical decline [2], but most of these studies on the relationship between BMI and physical functioning do not present data specific for men and women. A difference between men and women in the role of smoking for physical functioning was reported in the current study, in line with a recent review which suggests that the relative risk of smokers for impaired function is higher among men than among women [28]. For the association between physical activity and health-related quality of life, Liao et al. (2020) found a stronger positive association among men [29]. The current findings did not reach a significant difference between men and women in the association of physical activity with physical functioning, although a trend was observed.

Of the socio-demographic determinants, ‘living alone’ did not contribute to the difference between men and women in physical functioning. In contrast, both the quantity and quality of social support have been shown to have a greater impact on the well-being of women compared to men [30]. It is therefore recommended to include more extensive indicators for social contacts and social support in future studies, which were not included at baseline in the Doetinchem Cohort Study. The findings that educational level and work status were associated with physical functioning are in line with previous studies [31], but its contributing role for predominance of women in physical functioning limitations is not reported before. Intervention strategies aiming for equal opportunities regarding the work field, for example regarding promotion strategies, might decrease the difference in physical functioning between men and women.

The strengths of the current study include the use of a broad range of determinants, a large-scale data set and the use of a commonly used measure of physical functioning. The physical functioning domain of the SF-36 focuses on the ability to carry out specific physical activities, and to a lesser extent on daily routine and instrumental activities, and is therefore an adequate tool to measure physical functioning in an ageing cohort [23]. While interpreting the findings of the current study, some limitations should be taken into account. First, there is some selection bias towards a healthier and younger population, commonly found in cohort studies [14]. However, the associations between the determinants of chronic health problems are usually not likely to be affected by attrition [32]. In addition, there was no significant difference found in the response bias between men and women, and thus not affecting the current study of differences between men and women [32]. However, since women have a higher life expectancy this could lead to an overrepresentation of older women with poor physical functioning compared to men. Second, both the physical functioning and pain measures are self-reported and therefore bias may be gender specific: women may report more disability compared to men as a result of their increased subjective impression of functional loss and men are socially conditioned to neglect pain and disease [33]. However, it has also been demonstrated that women have similar degrees of self-reported limitation in physical functioning as men of the same age, health, and physical abilities [34]. In addition, the lower score among women compared to men is both found using self-report and performance-based measures [35]. Third, some relevant determinants for physical functioning were not included in the current study, e.g. cognitive functioning, vision and social contacts [5]. Cognitive functioning was not incorporated in our analyses, since cognition was measured in less than half of the sample and vision and social contacts were not included in the baseline measurement. It is recommended for future studies to take these variables into account. Fourth, a statistical approach was used to investigate ‘sensitivity’ and ‘exposure’ to determinants, but it is probably impossible to completely disentangle those two. Paradoxically, more limitations in physical functioning among women compared to men goes together with a lower mortality among women [4]. Other explanations for this sex/gender-health paradox than the determinant approach explored here, include sex differences in physiological aging such as differences between in chronic inflammation, in immunosenescence and in genes [11].

Conclusions

For the aim of explaining and reducing the ‘female disadvantage’ in physical functioning, the ‘sensitivity and exposure’ approach shows that in particular the difference between man and women in pain seems relevant. Hence, although an effective prevention program focusing on lifestyle-related determinants is known to improve physical functioning, it might not reduce the difference between men and women in physical functioning, where women report more limitations. Differences between men and women in physical functioning and health in general are persistent and require more attention from research, prevention and disease management in order to contribute to more equal opportunities in health.

Availability of data and materials

Data cannot be shared publicly because of confidentiality. Data are available from the Doetinchem Cohort Study (contact via https://www.rivm.nl/doetinchem-cohort-studie/onderzoekers/aanvraag-gegevens-dcs and doetinchemstudie@rivm.nl) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. The data underlying the results presented in the study are available from the Doetinchem Cohort Study. The Scientific Advisory Group ensures that proposals for the use of the Doetinchem Cohort Study data do not violate privacy regulations and are in keeping with informed consent that is provided by all participants. The authors of this study do not have any special access privileges to the data underlying this study that other researchers would not have.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Chatterji S, Byles J, Cutler D, Seeman T, Verdes E. Health, functioning, and disability in older adults - Present status and future implications. Lancet. 2015;385:563.

Van Der Vorst A, Zijlstra GAR, De Witte N, Duppen D, Stuck AE, Kempen GIJM, et al. Limitations in activities of daily living in community-dwelling people aged 75 and over: A systematic literature review of risk and protective factors. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0165127.

Chen CM, Chang WC, Lan TY. Identifying factors associated with changes in physical functioning in an older population. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:156.

Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Lin H, Han L, Allore HG. Comparisons Between Older Men and Women in the Trajectory and Burden of Disability Over the Course of Nearly 14 Years. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:280.

Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Büla CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: A systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:445.

Albanesi S, ?ahin A. The gender unemployment gap. Rev Econ Dyn. 2018

McLaughlin D, Vagenas D, Pachana NA, Begum N, Dobson A. Gender differences in social network size and satisfaction in adults in their 70s. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:671.

Raho E, Van Oostrom SH, Visser M, Huisman M, Zantinge EM, Smit HA, et al. Generation shifts in smoking over 20 years in two Dutch population-based cohorts aged 20–100 years. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:142.

Gell L, Meier PS, Goyder E. Alcohol consumption among the over 50s: international comparisons. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50:1.

Marques A, Peralta M, Naia A, Loureiro N, De Matos MG. Prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in 20 European countries, 2014. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:295.

Gordon EH, Hubbard RE. Physiological basis for sex differences in frailty. Current Opinion in Physiology. 2018.

Bartz D, Chitnis T, Kaiser UB, Rich-Edwards JW, Rexrode KM, Pennell PB, et al. Clinical Advances in Sex- and Gender-Informed Medicine to Improve the Health of All: A Review. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:574.

Steingrímsdóttir ÓA, Landmark T, Macfarlane GJ, Nielsen CS. Defining chronic pain in epidemiological studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2017. 20

Picavet HSJ, Blokstra A, Spijkerman AMW, Verschuren WMM. Cohort Profile Update: The Doetinchem Cohort Study 1987–2017: Lifestyle, health and chronic diseases in a life course and ageing perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1751.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Bost New Engl Med Cent [Internet]. 1993;1 v. (various pagings). Available from: http://books.google.com/books/about/SF_36_health_survey.html?id=WJsgAAAAMA AJ

van der Zee KI, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36, een handleiding_sf-36. NCG reeks meetinstrumenten?; 3. 1993;

Lakerveld J, Mackenbach JD, Horvath E, Rutters F, Compernolle S, Bárdos H, et al. The relation between sleep duration and sedentary behaviours in European adults. Obes Rev. 2016;17:62.

Kelly MJ, Dunstan FD, Lloyd K, Fone DL. Evaluating cutpoints for the MHI-5 and MCS using the GHQ-12: a comparison of five different methods. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(10)

Austin PC, Escobar M, Kopec JA. The use of the Tobit model for analyzing measures of health status. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:901.

Twisk J, Rijmen F. Longitudinal tobit regression: A new approach to analyze outcome variables with floor or ceiling effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:953.

Twisk JWR. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology: A practical guide, second edition. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A Practical Guide. 2011.

Fairchild AJ, McDaniel HL. Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: Mediation analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:1259.

Von Bonsdorff MB, Rantanen T, Sipilä S, Salonen MK, Kajantie E, Osmond C, et al. Birth size and childhood growth as determinants of physical functioning in older age. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1336.

Thapa S, Shmerling RH, Bean JF, Cai Y, Leveille SG. Chronic multisite pain: evaluation of a new geriatric syndrome. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31:1129.

Leveille SG, Bean J, Ngo L, McMullen W, Guralnik JM. The pathway from musculoskeletal pain to mobility difficulty in older disabled women. Pain. 2007;128:69.

Pieh C, Altmeppen J, Neumeier S, Loew T, Angerer M, Lahmann C. Gender differences in outcomes of a multimodal pain management program. Pain. 2012;153:197.

Keogh E, Eccleston C. Sex differences in adolescent chronic pain and pain-related coping. Pain. 2006;123:275.

Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Smoking as a risk factor for physical impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 cohort studies. J Addict Dis. 2020;38:19.

Liao YH, Kao TW, Peng TC, Chang YW. Gender differences in the association between physical activity and health-related quality of life among community-dwelling elders. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;

Antonucci TC, Akiyama H. An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles. 1987;17:737.

Molarius A, Berglund K, Eriksson C, Lambe M, Nordström E, Eriksson HG, et al. Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(2):125–33.

Boshuizen HC, Viet AL, Picavet HSJ, Botterweck A, van Loon AJM. Non-response in a survey of cardiovascular risk factors in the Dutch population: Determinants and resulting biases. Public Health. 2006; 22

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. The Lancet. 2020;296:565.

Louie GH, Ward MM. Sex disparities in self-reported physical functioning: True differences, reporting bias, or incomplete adjustment for confounding? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(6):1117–22.

Sialino LD, Schaap LA, Van Oostrom SH, Nooyens ACJ, Picavet HSJ, Twisk JWR, et al. Sex differences in physical performance by age, educational level, ethnic groups and birth cohort: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0226342.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all respondents, epidemiologists, and fieldworkers of the Municipal Health Service in Doetinchem for their contribution to the data collection for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) [849200005].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lena D. Sialino: Methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization and writing – review & editing. H. Susan J. Picavet: Investigation, literature research, visualization and writing – original draft. Hanneke A.H. Wijnhoven: Writing – review & editing. Anne Loyen: Formal analysis and writing – review & editing. W.M.Monique Verschuren: Investigation, supervision and writing – review & editing. Marjolein Visser: Methodology and writing – review & editing. Laura A. Schaap: Writing – review & editing. Sandra H. van Oostrom: Supervision and writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments since 1964, and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO). The protocols for subsequent rounds were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of TNO and University Medical Center Utrecht. All participants gave written informed consent

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Flowchart of the Doetinchem cohort Study, analyses of physical functioning (subscale SF-36) rounds and the final study population.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sialino, L.D., Picavet, H.S.J., Wijnhoven, H.A.H. et al. Exploring the difference between men and women in physical functioning: How do sociodemographic, lifestyle- and health-related determinants contribute?. BMC Geriatr 22, 610 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03216-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03216-y