Abstract

Background

Home healthcare (HHC) comprises clinical services provided by medical professionals for people living at home with various levels of care needs and health conditions. HHC may reduce care transitions from home to acute hospitals, but its long-term impact on homebound people living with dementia (PLWD) towards end-of-life remains unclear. We aim to describe the impact of HHC on acute healthcare utilization and end-of-life outcomes in PLWD.

Methods

Design: Systematic review of quantitative and qualitative original studies which examine the association between HHC and targeted outcomes. Interventions: HHC. Participants: At least 80% of study participants had dementia and lived at home. Measurements: Primary outcome was acute healthcare utilization in the last year of life. Secondary outcomes included hospice palliative care, advance care planning, continuity of care, and place of death. We briefly reviewed selected national policy to provide contextual information regarding these outcomes.

Results

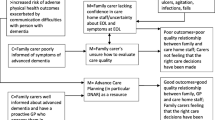

From 6831 articles initially identified, we included five studies comprising data on 4493 participants from USA, Japan, and Italy. No included studies received a “high” quality rating. We synthesised core properties related to HHC at three implementational levels. Micro-level: HHC may be associated with a lower risk of acute healthcare utilization in the early period (e.g., last 90 days before death) and a higher risk in the late period (e.g. last 15 days) of the disease trajectory toward end-of-life in PLWD. HHC may increase palliative care referrals. Advance care planning was an important factor influencing end-of-life outcomes. Meso-level: challenges for HHC providers in medical decision-making and initiating palliative care for PLWD at the end-of-life may require further training and external support. Coordination between HHC and social care is highlighted but not well examined. Macro-level: reforms of national policy or financial schemes are found in some countries but the effects are not clearly understood.

Conclusions

This review highlights the dearth of dementia-specific research regarding the impact of HHC on end-of-life outcomes. Effects of advance care planning during HHC, the integration between health and social care, and coordination between primary HHC and specialist geriatric/ palliative care services require further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Dementia is a life-limiting, progressive neurodegenerative syndrome affecting multiple cognitive and physical functions [1]. It is currently one of the most common causes of death in high-income countries, and globally, leads to an escalating need for end-of-life care [2,3,4]. People living with dementia (PLWD) are at a high risk of experiencing care transitions (i.e. transfer from home or care homes to acute hospital admission or emergency department visit), particularly towards the end-of-life [5,6,7,8]. Research in the USA and Taiwan has shown that potentially non-beneficial life-sustaining treatments such as tube feeding or mechanical ventilation are associated with care transitions [9,10,11] which may not improve the quality or length of life and are burdensome for the PLWD and their carers [7, 8, 10, 12]. Strategies to support this population with complex care needs and high care cost living and dying well in the community are vital [13, 14].

Palliative care has been considered an important service that contributes to the quality of care and fulfills the care needs of PLWD near the end-of-life [15]. According to World Health Organization’s definition, palliative care is an approach that involves the identification and management of problems associated with a life-threatening illness for patients and their families, prevents or relieves their suffering and improves their quality of life [16]. Its impact on reducing transitions for PLWD in care homes has been investigated [17,18,19]; however, the evidence on effective palliative care for PLWD living at home remains scarce and inconclusive [20, 21]. Furthermore, the provision of palliative care for PLWD is at a low coverage level across countries and the referral of the service is usually late in the potentially long, slow decline of disease trajectory when PLWD are approaching their end-of-life [11, 22, 23]. It is important to better understand the long-term impact on interventions such as home healthcare (HHC), which is usually provided earlier and more common for PLWD living at home, on reducing their high risk of acute healthcare utilisation or other health outcomes towards the end-of-life [15, 24, 25].

HHC comprises a spectrum of clinical care provided by healthcare professionals for people living at home with various levels of care needs and health conditions at different stages throughout the life course [26]. HHC types vary in terms of acuity, type of care provided, and degree of physician involvement, including patient-centered medical home, hospital at home, home-based primary care, physician or nurses house calls, skilled home healthcare, rehabilitation, and medication managements [26, 27]. HHC does not include case management, exercise coaching, social care (such as hygiene care or nutrition support) or self-management.

HHC is increasingly recognised as an integrated and value-based service for the ageing population including PLWD [14]. The demand for promoting better integrated and continuous care at home has been advocated by groups of PLWD, caregivers, and health professionals [27,28,29], and some reforms of policy to integrate the fragmented services and quality-based payment schemes to enhance multidisciplinary approach at a national level for improving quality of HHC is established in high-income countries [27, 29,30,31,32,33]. However, in the existing literature of HHC, only a few studies have focused on the PLWD and none of them reviewed long-term effects of HHC on acute healthcare utilisation and outcomes at the end-of-life [34, 35].

Aims

-

1.

To investigate the effects of primary HHC on the acute healthcare utilisation at the end-of-life among PLWD, including hospital, emergency department, intensive care, aggressive procedures, medications, and care transitions.

-

2.

To understand the association between primary HHC and use of hospice palliative care, continuity of care, and place of death among PLWD.

-

3.

To identify the policy or regulations that may influence the impact of HHC on the aforementioned outcomes among PLWD.

Methods

We registered the protocol on PROSPERO (CRD42019151250)and adhered to PRISMA statement in reporting the review [36].

Eligibility criteria

This review included peer-reviewed original articles of quantitative and qualitative studies. The inclusion and exclusion criteria on the study design, definition of PLWD and HHC and details of the study outcomes are summarised in Table 1. The comparison groups include any type of usual care, routine care or no intervention. In this study, home-based palliative care is not included in the HHC interventions because the effects of the services for PLWD have been reviewed [21], and palliative care is identified as an outcome of interest.

Search strategy and study selection

We applied a three-step search strategy: An initial limited search of Medline was performed, followed by the analysis of the terms used in titles and abstracts, and of the index terms used to describe articles. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms for ‘dementia’, ‘home healthcare’, and a series of outcomes such as ‘acute healthcare utilisation’, ‘continuity of care’, ‘palliative care’ or ‘place of death’ were then undertaken across five electronic databases, including OVID Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library and CINAHL, from inception to September 2020. In the third search, the reference list of all identified articles was searched for additional studies. Search terms were used in combination with MESH headings, controlled vocabulary and free-text terms to cover the topics and detail (see Supplementary file).

Two authors (PJC and LS) read the abstracts of half of the retrieved records to identify potentially relevant publications. These publications were marked as ‘include’ or ‘uncertain’ after the exclusion of irrelevant studies. A random 15% of selected records were independently checked by a second reviewer (JYL). The two authors then retrieved the full texts of identified studies and screened them according to the eligibility criteria. The final list of articles was checked by the three authors and any disagreements were discussed with the third reviewer (ELS) to reach consensus. We constructed a PRISMA flowchart to describe the selection process and a table containing excluded studies with the rationale for exclusion. References were managed and deduplicated by citation management software.

Data extraction

We extracted relevant data into a standardised table using Microsoft Excel. The table format was pilot-tested on three articles to ensure consistency and was approved by the research team. Extracted data included country, time, study design, data source and collection, research questions (aims), participants, content of interventions, comparison, and outcomes. Information from included studies was extracted by PJC and JYL independently and checked for accuracy by RM. Discrepancies were discussed with ELS to reach consensus.

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) toolkit was used by PJC and LS to appraise the quality of the included studies [37]. Studies were rated as strong, moderate or weak based on the following components: study design, data collection method, bias of selection and outcome measurements, intervention integrity, confounding factors, appropriate analysis and implication for practice. Discrepancies were discussed with RM to reach a consensus.

Data synthesis

We narratively described the effectiveness of HHC-related outcomes. We used an adapted multilevel framework of Ferlie and Shortell [38] to synthesise core properties of HHC. The empirically derived model was used for summarising and classifying the various characteristics related to end-of-life care provision in care homes across countries and focus on three levels of the implementation: macro- such as national policy, legislation, or financial provision; meso- such as training or service model/framework; micro- effects or components in an individual programme [39]. We were unable to conduct a meta-analysis because of clinical and statistical heterogeneity across studies. Results were set out in a table with data reported from the included study (e.g. p-values).

Results

Of all retrieved studies, five met the inclusion criteria. The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Studies’ characteristics

We identified five studies; one prospective cohort study [40], two retrospective cohort studies [41, 42], and two case-control studies (Table 2) [43, 44]. No clinical trials or qualitative studies were included. In total, 4493 participants with dementia were included in these quantitative papers. Three studies (3936 participants, 87.6%) were conducted in the USA [41, 42, 44], and one each from Italy [40] and Japan [43]. All studies included both males and females and most participants were over 80 years old. The HHC provided in these five studies were all forms of home-based primary care.

Micro-level

Four studies mentioned that the HHC was provided by the multidisciplinary team [40, 42,43,44]. HHC in the other study emphasised advance care planning in a nurse-led programme [41]. Only one study mentioned the duration of the HHC intervention [42], and no study reported the time between dementia diagnosis and the first HHC.

Two studies compared outcomes in people receiving HHC with those in nursing home care [40, 42], and another study compared outcomes of treatments for acute events between the HHC group and the hospitalised group [43]. Four studies investigated outcomes related to end-of-life issues or palliative care [40,41,42, 44], whereas survival and mortality rate was the main outcome outcomes in the other study [43].

Meso-level

Three studies mentioned coordination with social workers, non-clinical social care support and external specialists such as palliative care consultants or geriatricians in HHC [40, 42, 44].

Macro-level

We did not find information on national policy or financial schemes that influence HHC for PLWD in the selected articles.

Quality of the evidence

No study received a high-quality rating (Table 2). The main reasons for low scores were authors not taking account of confounding factors appropriately in the analysis and the absence or insufficiency of follow-up period because of study design.

Impact of HHC on end-of-life outcomes for PLWD

Results identified from included papers were summarised in Table 3. All the observed impacts were at the micro-level.

Acute healthcare utilisation in the last year of life

Three studies have reported results regarding our primary outcomes of interest [40,41,42]. In the Italian cohort study, a higher percentage of HHC physicians felt it difficult to decide whether PLWD should be hospitalised or not than physicians practising in nursing homes (25.5% vs. 3.1%, p < 0.001) when patients’ estimated survival was fewer than 15 days [40]. In the USA, however, Mitchell et al. reported that fewer people with advanced dementia receiving HHC were hospitalised within 90 days before the last Minimum Data Set assessment compared with those cared for in nursing homes (31.5% vs. 43.7%, p < 0.001) during the period from 1998 to 2001 [42]. In terms of specific procedures, fewer people in the HHC group were given life-supporting therapies such as oxygenation or feeding tube than those in the nursing home group at the end-of-life.

Jennings et al. described the effects of an HHC programme in California, which specifically focused on advance care planning including Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), on end-of-life care in PLWD [41]. A higher proportion of PLWD who received HHC with the completion of POLST experienced hospitalisations in the last 6 months of life compared with those receiving HHC but without a POLST. No significant difference was found between the length of hospital stay, intensive care unit admission, and frequency of emergency department visits between the two groups.

Hospice palliative care use

In Toscani’s study, physicians in the nursing home group were more likely to consider/make decisions that focused on reducing suffering or on improving quality of death for PLWD than physicians providing HHC [40]. Two studies in the USA reported a higher percentage of HHC recipients who used hospice or were referred to hospice care before their death compared with nursing home residents or the control group [42, 44]. In California, Jennings et al. demonstrated that PLWD who received HHC with a completed POLST were more likely to have hospice care discussion or consultations, use hospice care when they died and died at home than HHC recipients who did not have a completed POLST [41].

Advance care planning

Only Mitchell’s study indicated that fewer HHC recipients had advance directives before death than did nursing home residents, despite a higher proportion of HHC recipients having a life expectancy of less than 6 months [42].

Place of death

Each study in the USA and Japan reported this outcome [41, 43]. A higher proportion of PLWD in HHC with POLST died at home than those in HHC without POLST. Information regarding PLWD’s preferences of place of care/ death is not found.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review that explored the association between primary HHC and end-of-life outcomes among homebound PLWD who are at a high risk of mortality [24, 42]. The comparison groups and outcomes measured in the five included studies vary, and we found the results were heterogeneous and very limited to conclusively examine the effects of HHC on end-of-life outcomes. The existing literature suggests that HHC may be associated with an inverse risk of acute healthcare utilisation in the early and late periods (e.g. 90 vs 15 days before death) of the disease trajectory towards the end-of-life in PLWD. HHC seems to increase referrals to hospice palliative care, whilst advance care planning may influence the effects of HHC on end-of-life outcomes. HHC providers’ difficulty in making treatment decisions for PLWD at the end-of-life may require further training and external support. The coordination between HHC and social care is important but not well implemented and investigated.

Micro-level

The differential effects of HHC on acute healthcare utilisation among PLWD in the early or late period imply different care needs at various stages in the disease trajectory among PLWD, for which distinct components and models of HHC service may meet their needs better. A systematic review showed that home-based primary care mostly reduces the events and length of hospitalisation [35]; however, this effect was observed within 1 year after HHC but not followed up to the recipients’ death. In addition, we have not been able to clarify the influence of the duration, continuity, or intensity of HHC from the current literature. Among homebound PLWD approaching the end-of-life, identifying care needs and treatment decisions are complicated because the person may be unable to express their care preferences [40]. Multidisciplinary approaches in HHC may be beneficial to PLWD towards the end-of-life [40, 42,43,44], but none of the selected studies have examined the effectiveness of skill mix across various professions or quantified the contribution of each discipline.

Given that people with dementia may lose the capacity to make decisions, advance care planning in HHC may substantially influence end-of-life outcomes. A recent review showed that advance care planning for PLWD was associated with decreased hospitalisations and increased concordance between prior preferences and actual care received [45]. In primary care settings, key barriers of professionals to conduct advance care planning for PLWD includes the time restraints of medical staffs; the insufficiently trusted relationship between PLWD and medical staffs due to infrequent contact; staffs’ attitude, knowledge, skills, and moral considerations towards talking end-of-life issues and death; and inadequate reimbursement [46, 47]. However, the context of home visits is preferred by PLWD and family caregivers because it is a trusted environment to have care plan conversations addressing not only medical but also non-medical preferences, such as valued abilities and activities, family support and relationship, and place of care/ death [46, 48]. Both interactive training and clinical practice of conducting advance care planning during HHC can be facilitated by involving interdisciplinary professionals, such as nurses, social workers, or care managers [46, 48].

Meso-level

Providing training programmes and seamless palliative care support from external specialists to HHC practitioners may improve the capability of primary end-of-life care in the home setting [49, 50]. HHC physicians were less likely to initiate palliative care for PLWD [40], even though eventually the specialist palliative care or hospice referral is higher for people in the HHC group than those in the nursing home or control group [42, 44]. Primary healthcare workers may more likely to consider that palliative care is not meaningful in PLWD than in people with other life-limiting illnesses [51] or only acknowledged its benefit in terminal care, so they refer the people to the service late [49]. The resistance of timely palliative care approaches provided by HHC professionals, such as symptom management and initiating advance care planning discussion, can be further overcome through education, skills training, and discussion of moral dilemmas [47, 49, 52]. Further service commissioning and integration between HHC teams and external specialists such as geriatricians or palliative care may contribute to PLWD living and dying well at home [23].

Good-quality HHC requires strong coordination between health and social care services to achieve better end-of-life outcomes. A UK cohort study found that the need for social care services increased among PLWD towards the end-of-life [23], and the lack of social care support at home may lead to a higher risk of acute healthcare use [53]. In the selected studies, only one US study assessed the use of social services in the HHC setting and found such services were not used to its full potential, showing that the coordination between health and social care may be an area for improvement [44]. The barriers of care integration for PLWD towards the end-of-life may include the conflicting relationships and communication between disciplines and settings, lengthy referral processes, minimal care planning, diffuse responsibility, and fragmented reimbursement system [50, 54]. At the local services, organising the cross disciplinary network between healthcare and social care sectors, increasing the communication and establishing the practice guidelines with shared goals, peer supporting to formal and family caregivers, and highlighting good practices can improve the quality of integrated care [50].

Macro-level

Reform of national policy and payment schemes would be vital in promoting better care for individuals [55, 56], or in building up interdisciplinary collaborations and delivery systems between health and social care services [50]. However, contextual information, including descriptions of the related policy and payment schemes in each country, was not mentioned in the selected papers.

To understand this context better, we summarise some international examples through a brief policy review and discussion in our research network (Table 4), including those from where the five papers of this review originated (USA, Italy and Japan) and the top-ranked countries in related regions in the Quality of Death Index Report [56], such as Australia, Canada, UK, and Taiwan. The key lessons from the policy comparison are building up person-centred continuous care at home, with a seamless connection between primary care and palliative care throughout the disease trajectory, quality- and value-based payment for interdisciplinary collaboration, as well as comprehensive networking with coordination between health and social care sectors [26,27,28, 31].

Strengths and limitations

We comprehensively and systematically searched the literature by applying a wide range of search terms including synonyms of HHC and types of HHC programmes. The identified studies were rigorously checked by quality assessment tools. The international members of our research team provided insights and interpretation.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the majority of studies evaluating the effects of HHC had short follow-up periods, often less than 12 months after the initiation of HHC [34, 63, 64]. Data about end-of-life outcomes that occurred within the final years before death were neither investigated nor analysed separately, leading to fewer papers meeting our selection criteria [64, 65]. Secondly, none of the included studies were rated as high quality in critical appraisal. Outcomes were heterogeneous, and it was not possible to pool data and perform a meta-analysis of the findings. In addition, the lack of information about the duration, intensity or components of HHC interventions meant that we could not explore the ‘dose-response’ relationship between characteristics of HHC and outcomes [66]. Finally, the small sample size in the HHC group and lack of random sample selection may lead to poor external validity [67].

Implications for research and practice

The sparse evidence in our review suggests that the role of primary HHC may have been overlooked as a key service that could deliver better quality end-of-life care for PLWD. HHC services may vary widely across countries, and details of the components and contextual factors of HHC and how they are implemented are important to evaluate the effects of complex interventions, which were not reported in the included studies [68]. For future studies, it is essential to better understand the effective components of HHC, such as advance care planning, and the mechanism of how they influence end-of-life outcomes for PLWD.

Conducting a randomised trial or a prospective cohort study with a longer follow-up period of HHC would be challenging in practice [24, 35]. A more pragmatic, hybrid paradigm incorporating quality improvement or service evaluation may be more useful and realistic to conduct [69]. Large real-world datasets containing whole population samples, with complete follow-up are also good sources to evaluate HHC programmes throughout the disease trajectory, though appropriate and robust methodologies should be applied [67, 70,71,72]. This would reduce selection bias and prevent missing data due to the attenuation of study cohorts. Current metrics of care quality, which were developed for individual diseases, are not holistic and do not capture more value-based dimensions such as continuity of care or level of care integration [73].

Regarding the clinical practice, advance care planning, comprehensive geriatric assessment, and a palliative approach which focuses on patients’ care preferences and improving quality of life should be emphasised in HHC for PLWD [15, 74, 75]. Stakeholders should enhance education for HHC users and providers, strengthen the training of the interdisciplinary workforce, and promote a service model supported by external professionals including social care or even telemedicine during the pandemic to meet complex end-of-life care needs in PLWD [23, 26, 49, 74]. Policymakers are encouraged by the experience of national policy and payment scheme reform in some countries to build up the continuously integrated care framework that improves the synergy of various services [26, 27, 74].

Conclusion

This review added the new knowledge that different care needs at various stages in the disease trajectory towards the end-of-life among PLWD urge more integrated services with effective components to respond to their demand better. Effects of advance care planning, multidisciplinary approach, integration between health and social care, and coordination between primary HHC and specialists’ support in local healthcare networks for better continuity of care at home should be emphasised in clinical practice and policy-making. Population-based large databases may provide opportunities to examine more clearly the long-term impact of HHC and its synergy with other clinical services on end-of-life outcomes in a longitudinal study design.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary files.

References

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(2617)31363-31366 Epub 32017 Jul 31320.

Kramarow EA, Tejada-Vera B. Dementia Mortality in the United States, 2000-2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(2):1–29. PMID: 31112120.

Patel V. Deaths registered in England and Wales (series DR): 2017. London: Office for National Statistics; 2018.

Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, Gomes B, Harding R. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883–e892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31129125; PMCID: PMC6560023.

Shepherd H, Livingston G, Chan J, Sommerlad A. Hospitalisation rates and predictors in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019;17:130.

Sleeman KE, Perera G, Stewart R, Higginson IJ. Predictors of emergency department attendance by people with dementia in their last year of life: retrospective cohort study using linked clinical and administrative data. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:20–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.1006.2267 Epub 2017 Aug 1022.

Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1100347. PMID: 21991894; PMCID: PMC3236369.

Chen YH, Ho CH, Huang CC, et al. Comparison of healthcare utilization and life-sustaining interventions between elderly patients with dementia and those with cancer near the end of life: a nationwide, population-based study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2545–51.

Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, et al. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:359–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2008.0168.

Teno JM, Gozalo P, Khandelwal N, et al. Association of Increasing use of mechanical ventilation among nursing home residents with advanced dementia and intensive care unit beds. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1809–16.

Chen PJ, Liang FW, Ho CH, et al. Association between palliative care and life-sustaining treatments for patients with dementia: a nationwide 5-year cohort study. Palliat Med. 2018;32:622–30.

Aaltonen M, Raitanen J, Forma L, Pulkki J, Rissanen P, Jylha M. Burdensome transitions at the end of life among long-term care residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:643–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.1004.1018 Epub 2014 Jun 1017.

Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults. Health Aff. 2021;21:01470.

WHO. The growing need for home health care for the elderly. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo: World Health Organization; 2015.

van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med. 2014;28:197–209.

WHO. Palliative care. Key Facts: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care, retrieved 8 May 2020

Murphy E, Froggatt K, Connolly S, et al. Palliative care interventions in advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD011513. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD14011513.pub14651852.

Wichmann AB, Adang EMM, Vissers KCP, et al. Decreased costs and retained QoL due to the 'PACE steps to Success' intervention in LTCFs: cost-effectiveness analysis of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2020;18:258. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-12020-01720-12919.

Sampson EL, Anderson JE, Candy B, et al. Empowering better end-of-life dementia care (EMBED-care): a mixed methods protocol to achieve integrated person-centred care across settings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35:820–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5251 Epub 2020 Jan 1015.

Godard-Sebillotte C, Le Berre M, Schuster T, Trottier M, Vedel I. Impact of health service interventions on acute hospital use in community-dwelling persons with dementia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0218426.

Miranda R, Bunn F, Lynch J, Van den Block L, Goodman C. Palliative care for people with dementia living at home: a systematic review of interventions. Palliat Med. 2019;33:726–42.

De Vleminck A, Morrison RS, Meier DE, Aldridge MD. Hospice Care for Patients with Dementia in the United States: a longitudinal cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:633–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.1010.1003 Epub 2017 Nov 1016.

Sampson EL, Candy B, Davis S, et al. Living and dying with advanced dementia: a prospective cohort study of symptoms, service use and care at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2018;32:668–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317726443 Epub 0269216317722017 Sep 0269216317726418.

Boling PA, Leff B. Comprehensive longitudinal health care in the home for high-cost beneficiaries: a critical strategy for population health management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1974–6.

Leniz J, Higginson IJ, Stewart R, Sleeman KE. Understanding which people with dementia are at risk of inappropriate care and avoidable transitions to hospital near the end-of-life: a retrospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2019;48(5):672–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz052. PMID: 31135024.

Ritchie CS, Leff B. Population Health and Tailored Medical Care in the Home: the Roles of Home-Based Primary Care and Home-Based Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(3):1041–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 29031914.

Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B, et al. The future of home health care: a strategic framework for optimizing value. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2016;28:262–78.

Morikawa M. Towards community-based integrated care: trends and issues in Japan's long-term care policy. Int J Integr Care. 2014;14:e005. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.1066 eCollection 2014 Jan.

Riley G. Doctor-led Health Care Homes to address continuity of care gaps. Available at: https://www.wapha.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Medicus-May-2016.pdf (accessed 7th Nov 2021).

US CMS. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. 2016. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/bundled-payments (accessed 4th July 2021).

Liao J-Y, Chen P-J, Wu Y-L, et al. HOme-based longitudinal investigation of the multidiSciplinary team integrated care (HOLISTIC): protocol of a prospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:511.

Sudo K, Kobayashi J, Noda S, Fukuda Y, Takahashi K. Japan's healthcare policy for the elderly through the concepts of self-help (Ji-jo), mutual aid (go-jo), social solidarity care (Kyo-jo), and governmental care (Ko-jo). Biosci Trends. 2018;12:7–11. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2017.01271 Epub 02018 Feb 01226.

Canada H. A Common Statement of Principles on Shared Health Priorities. 2017, Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/health-agreements/principles-shared-health-priorities.html (accessed 7th Nov 2021).

Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD007491.

Stall N, Nowaczynski M, Sinha SK. Systematic review of outcomes from home-based primary care programs for homebound older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:2243–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13088 Epub 12014 Nov 13084.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Programme. CAS. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists 2018 Available at: casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79:281–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00206.

Froggatt K, Payne S, Morbey H, et al. Palliative care development in European care homes and nursing homes: application of a typology of implementation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(550):e557–550.e514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.1002.1016 Epub 2017 Apr 1012.

Toscani F, van der Steen JT, Finetti S, et al. Critical decisions for older people with advanced dementia: a prospective study in long-term institutions and district home care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(535):e513–20.

Jennings LA, Turner M, Keebler C, et al. The effect of a comprehensive dementia care management program on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:443–8.

Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:808–16.

Arai Y, Suzuki T, Jeong S, et al. Effectiveness of home care for fever treatment in older people: a case-control study compared with hospitalized care. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20:482–7.

Wilson K, Bachman SS. House calls: the impact of home-based Care for Older Adults with Alzheimer’s and dementia. Soc Work Health Care. 2015;54:547–58.

Wendrich-van Dael A, Bunn F, Lynch J, Pivodic L, Van den Block L, Goodman C. Advance care planning for people living with dementia: an umbrella review of effectiveness and experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;107:103576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103576 Epub 102020 Mar 103520.

Tilburgs B, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, Weidema M, Perry M, Engels Y. The importance of trust-based relations and a holistic approach in advance care planning with people with dementia in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-12018-10872-12876.

Keijzer-van Laarhoven AJ, Touwen DP, Tilburgs B, et al. Which moral barriers and facilitators do physicians encounter in advance care planning conversations about the end of life of persons with dementia? A meta-review of systematic reviews and primary studies. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e038528. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-032020-038528.

Tilburgs B, Koopmans R, Schers H, et al. Advance care planning with people with dementia: a process evaluation of an educational intervention for general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-12020-01265-z.

Zapponi S, Ascari MC, Feracaku E, et al. The palliative care in dementia context: health professionals point of view about advantages and resistances. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:45–54. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v23789i23754-S.27198.

Jones L, Candy B, Davis S, et al. Development of a model for integrated care at the end of life in advanced dementia: a whole systems UK-wide approach. Palliat Med. 2016;30:279–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315605447 Epub 0269216315602015 Sep 0269216315605449.

Beernaert K, Deliens L, Pardon K, et al. What are Physicians' reasons for not referring people with life-limiting illnesses to specialist palliative care services? A Nationwide Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137251. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137251 eCollection 0132015.

Munday D, Boyd K, Jeba J, et al. Defining primary palliative care for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2019;394:621–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(1019)31830-31836.

van Weel JM, Renehan E, Ervin KE, Enticott J. Home care service utilisation by people with dementia-a retrospective cohort study of community nursing data in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27:665–75.

Kupeli N, Leavey G, Harrington J, et al. What are the barriers to care integration for those at the advanced stages of dementia living in care homes in the UK? Health care professional perspective. Dementia (London). 2018;17:164–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301216636302 Epub 1471301216632016 Mar 1471301216636301.

Barker K. A New settlement for health and social care 2014. The King’s fund (online), Available at: www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/new-settlement-health-and-social-care. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

EIU. The Quality of Death Index 2015 – Ranking palliative care across the world. . The Economist Intelligence Unit, Available at: eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/2015%20EIU%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Index%20Oct%2029%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed rch Mar 2021.

Australian DoH. About the Home Care Packages Program. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/home-care-packages-program/about (accessed 7th Nov 2021).

Australian DoH. Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP). Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/commonwealth-home-support-programme-chsp (accessed 7th Nov 2021).

Di Fiandra T, Canevelli M, Di Pucchio A, Vanacore N. The Italian dementia National Plan. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015;51:261–4. https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_4415_4404_4402.

Chen CF, Fu TH. Policies and transformation of long-term care system in Taiwan. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2020;24:187–94. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.4220.0038 Epub 2020 Sep 4224.

NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan 2019. NHS England (online), Available at: www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

Government H. Better care fund: policy framework 2019–20. GOV.UK (online), available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/821676/Better_Care_Fund_2019-20_Policy_Framework.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

Zimbroff RM, Ritchie CS, Leff B, Sheehan OC. Home-based primary and palliative Care in the Medicaid Program: systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(1):245–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16837. Epub 2020 Sep 21. PMID: 32959375.

Wang J, Caprio TV, Simning A, et al. Association between home health services and facility admission in older adults with and without Alzheimer's disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:627.

Nakanishi M, Nakashima T, Shindo Y, Niimura J, Nishida A. Japanese care location and medical procedures for people with dementia in the last month of life. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51:747–55.

Schünemann H, Hill S, Guyatt G, Akl EA, Ahmed F. The GRADE approach and Bradford Hill's criteria for causation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:392–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.119933 Epub 112010 Oct 119914.

Hunt LJ, Lee SJ, Harrison KL, Smith AK. Secondary analysis of existing datasets for dementia and palliative care research: high-value applications and key considerations. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:130–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0309 Epub 2017 Dec 1021.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258.

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ. 2007;334:455–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE.

Harrison KL, Leff B, Altan A, Dunning S, Patterson CR, Ritchie CS. What's happening at home: a claims-based approach to better understand home clinical care received by older adults. Med Care. 2020;58:360–7.

Chen PJ, Ho CH, Liao JY, et al. The association between home healthcare and burdensome transitions at the end-of-life in people with dementia: a 12-year Nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9255. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249255.

Miranda R, Smets T, De Schreye R, et al. Improved quality of care and reduced healthcare costs at the end-of-life among older people with dementia who received palliative home care: a nationwide propensity score-matched decedent cohort study. Palliat Med. 2021;10:02692163211019321.

Leff B, Carlson CM, Saliba D, Ritchie C. The invisible homebound: setting quality-of-care standards for home-based primary and palliative care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1008.

Evans CJ, Ison L, Ellis-Smith C, et al. Service delivery models to maximize quality of life for older people at the end of life: a rapid review. Milbank Q. 2019;97:113–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12373.

Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-12018-10332-12902.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jun Hamano at the University of Tsukuba and Dr. Kirsten Moore at the National Ageing Research Institute for their advice about the national policy in Japan and Australia. We thank Enago.com for their expertise and assistance of English editing.

Funding

Ping-Jen Chen is supported by Government Scholarship for Overseas PhD Study, Ministry of Education, Taiwan, for conducting this research (grant reference: 1051165–1-UK-002). Elizabeth L Sampson’s post is supported by Marie Curie core grant funding, Grant (MCCC-FCO-16-U). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: PJC, RM, LVdB, ELS. Acquisition of data: PJC, LS. Analysis and interpretation of data: PJC, LS, RM, JYL. Drafting of the manuscript: PJC, LS. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required for this systematic review of existing published literature.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary file.

Search strategy and terms in electronic databases.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, PJ., Smits, L., Miranda, R. et al. Impact of home healthcare on end-of-life outcomes for people with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 22, 80 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02768-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02768-3