Abstract

Aims

While the frailty index (FI) is a continuous variable, an FI score of 0.25 has construct and predictive validity to categorise community-dwelling older adults as frail or non-frail. Our study aimed to explore which FI categories (FI scores and labels) were being used in high impact studies of adults across different care settings and why these categories were being chosen by study authors.

Methods

For this systematic scoping review, Medline, Cochrane and EMBASE databases were searched for studies that measured and categorised an FI. Of 1314 articles screened, 303 met the eligibility criteria (community: N = 205; residential aged care: N = 24; acute care: N = 74). For each setting, the 10 studies with the highest field-weighted citation impact (FWCI) were identified and data, including FI scores and labels and justification provided, were extracted and analysed.

Results

FI scores used to distinguish frail and non-frail participants varied from 0.12 to 0.45 with 0.21 and 0.25 used most frequently. Additional categories such as mildly, moderately and severely frail were defined inconsistently. The rationale for selecting particular FI scores and labels were reported in most studies, but were not always relevant.

Conclusions

High impact studies vary in the way they categorise the FI and while there is some evidence in the community-dweller literature, FI categories have not been well validated in acute and residential aged care. For the time being, in those settings, the FI should be reported as a continuous variable wherever possible. It is important to continue working towards defining frailty categories as variability in FI categorisation impacts the ability to synthesise results and to translate findings into clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last decade, there has been exponential growth in the number of ‘FI studies’ published in peer-reviewed journals. The frailty index (FI) represents the accumulated deficit model of frailty [1] and is a continuous variable (ranging from zero to a theoretical maximum of one) derived from a list of potential health deficits [2]. Increasingly, FI scores are being used to assign individuals to frailty categories.

In their 2007 study, Rockwood and colleagues [3] found that an FI = 0.25 was the ‘crossing point’ of robust and frail groups (as measured by the phenotypic model of frailty) and predicted death and institutionalisation. These results were consistent with findings of an earlier study by this group. In 2005, Rockwood et al. [4] showed that the FI and Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS; a scale of increasing functional dependence) were highly correlated and independently predicted adverse outcomes, and that an FI = 0.25 lay between CFS category 4 (‘apparently vulnerable’, mean FI = 0.22) and CFS category 5 (‘mildly frail’, mean FI = 0.27). Together, Rockwood et al.’s studies demonstrated that an FI = 0.25 had construct and predictive validity to categorise community-dwelling older adults as frail or non-frail.

Nevertheless, a variety of FI categories have emerged in the literature. Our study had two key aims: firstly, to explore which FI categories (FI scores and labels) were being used in high impact studies of adults in the community, residential aged care and acute care; and secondly, why these categories were being chosen by study authors.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) criteria [5]. The protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework Registry.

Search strategy

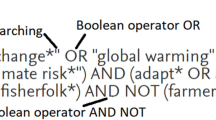

A search of Medline, Cochrane and EMBASE databases was conducted in May 2020 and again in March 2021. Search terms included ‘frailty index’, ‘acute care hospital’, ‘community’ and ‘residential care’. The full search strategy is included in the Appendix.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they used an FI that met the criteria as set out by Searle and colleagues [2] and the FI was categorised in some way (i.e., an FI score(s) delineated labelled sub-categories). Included studies could be of any design, but were to be conducted in a human adult population in one of three settings: community, acute care or residential aged care. Studies were excluded if they were not an original study (e.g., a protocol or review paper), if only the abstract was available or if there were not written in English.

Study selection

After removing duplicates, one reviewer (IK) independently screened the record titles and abstracts. Two reviewers (IK, NR) independently screened the full-text articles and disagreements were resolved by consensus and discussion with a third reviewer as required. Eligible studies were separated into the three settings of interest. A field-weighted citation impact (FWCI) score was calculated for each study. Sourced from SciVal, the FWCI compares the number of citations a publication receives to the average number of citations received by other similar publications in the Scopus database [6]. Similar publications are those that have the same publication year, publication type and discipline. Consequently, newer publications are not disadvantaged using this methodology. The ten studies with the highest FWCIs (i.e., the 10 ‘highest impact’ studies) from each setting underwent data extraction.

Data extraction and analysis

Three reviewers (IK, NR, EG) performed data extraction and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Extracted study data included country, publication date, study design and sample size. FI data included mean, FI scores and labels and justification provided by the study author(s) for these FI categories.

Results

Study characteristics

The search strategy yielded 1512 studies and 303 were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). Of the 30 highest impact studies (i.e., 10 highest impact studies from each setting), 29 were published in the last decade (Table 1). Twenty-one studies were cohort design and seven were cross-sectional. The majority were conducted in North America. Study sample size ranged from 50 to 931,541. The mean FI of the populations described in the studies ranged from 0.07 to 0.42.

FI categories

In studies of community-dwelling adults, an FI = 0.25 delineated frail and non-frail individuals in three studies [10, 14, 15], all of which referenced Rockwood and colleagues’ 2007 study [3]. An FI = 0.21 was used in three studies [9, 11, 13]. One referenced Rockwood et al.’s CFS validation study [4] and the other two referenced Hoover and colleagues’ study [12], which demonstrated the predictive validity of this FI cut-off in older community-dwellers. In a large cohort study using the electronic FI (eFI), Clegg et al. [7] used quartiles to define fit (FI < 0.12) versus frail (FI > 0.12) categories. Subsequently, two high impact UK studies adopted these eFI categories for their analyses [16, 17].

In the acute care setting, an FI = 0.25 was the most common score used to determine frailty [18,19,20, 25, 27]. One study referenced Rockwood and colleagues’ community-dweller study [4]. The other studies either provided no justification, referenced studies that did not use FI categories or referenced other papers written by the same authors. Incident adverse outcomes were used to delineate frailty severity (i.e., less or more frail; least frail and least fit) in two studies [26, 28].

In studies of adults residing in residential aged care, there was even greater variability. One study defined frailty as an FI ≥ 0.25 [39] and referenced studies that did not evaluate the validity of this cut-off. Four studies utilised an FI = 0.21 to define frailty [42,43,44] and all referenced (directly or indirectly) the community-dweller study by Hoover et al. [12]. Three studies defined frail as an FI > 0.30 [35, 37, 45]. Two referenced other papers written by the same authors and one referenced a study that demonstrated the predictive validity of similar FI categories in community-dwellers [38].

Across the settings, additional categories such as robust, pre-frail, mildly, moderately and severely frail were defined inconsistently. Methods included examining data spread (such as FI quartiles) [7, 8, 16, 17, 29, 32] and sensitivity/specificity analyses (in relation to adverse outcomes) [26, 28]. Three studies [11, 33, 44], two of which were conducted in residential aged care, adopted the categories that Hoover et al. [12] validated.

Discussion

This scoping review demonstrated variability in FI categorisation in high impact studies of community-dwellers, acute care patients and adults living in a residential aged care. An FI = 0.25 was the most commonly used score to determine frailty, although this was used in less than half of all studies. Greatest variability was seen in residential aged care studies. The rationale for using particular FI categories was reported in most studies, but was not always relevant.

Fourteen studies referenced Rockwood et al. [3, 4] and Hoover et al. [12] as justification for a variety of FI cut-offs and labels. Researchers used the mean FI values reported in Rockwood and colleague’s CFS study [4] to define FI categories, but not all in the same way. While some categories (e.g., frail = FI > 0.21 versus FI > 0.25) were similar, others (e.g., frail = FI > 0.45 versus most frail = FI ≥ 0.45) probably captured different groups of adults. In their 2013 study, Hoover and colleagues [12] tested the predictive validity of published cut-offs (including FI > 0.21 [4], > 0.25 [3] and > 0.35 [38]) in an older community-dwelling population. Using stratum-specific likelihood ratios for hospital-related outcomes, they identified four frailty categories (non-frail = FI < 0.1, pre-frail = 0.1 < FI ≤ 0.21, frail = FI > 0.21 and most frail = FI ≥ 0.45). These categories align with Rockwood et al.’s study [4], where the mean FIs of very fit (CFS 1) and severely frail (CFS 7) adults were 0.09 and 0.43, respectively.

Some FI categories validated in community-dwelling populations have been used in studies of adults in acute and residential aged care. It is debatable whether FI categories should vary by setting. Certainly, in these care settings, a greater proportion of adults are frail and, as a result, dichotomizing the FI into frail and non-frail is suboptimal. For example, in their recent cross-sectional study of Australian aged care residents, Ambagtsheer and colleagues [42] found that using an FI score of 0.21 to delineate frail and non-frail residents yielded a frailty prevalence rate of 43.6%. Thus, the heterogeneity of almost half of the residents’ health statuses would not be captured using this categorisation.

Frailty prevalence rates are also high in the acute setting. For example, Joseph and colleagues [18] found that 44% of geriatric trauma patients were frail (FI > 0.25). In a previous study by our group [46], the negative predictive value for an FI > 0.40 was high (84–98%) for all adverse outcomes, including individual geriatric syndromes, in older inpatients. This study was not included in this scoping review as the authors did not use this FI value to define FI categories (such as FI > 0.4 = more frail or FI < 0.40 = less frail). Nevertheless, two studies included in this review yielded similar results: an FI > 0.46 and an FI > 0.40 predicted adverse outcomes in elderly patients in intensive care and rehabilitation, respectively [26, 28]. These data indicate that an FI ≥ 0.40 is a valid cut-off for severe frailty in the acute care setting. Overall, further data are required to validate mild, moderate and severe categories and to determine whether these categories are applicable across settings.

The major limitation of this scoping review is that data were extracted from 11% of eligible studies. The decision to extract data from the studies with the highest FWCIs was primarily pragmatic. This study not only aimed to describe which FI categories were being used in the literature but also aimed to examine why these categories were being chosen. It was not feasible to extract and present data with this degree of granularity from over 300 studies. Studies with the highest FWCIs are most likely to influence and to have influenced adoption of FI categories in clinical practice and research. Therefore, extracting and synthesising data from these studies generates meaningful results relevant to both spheres. Overall, this methodology yielded highly heterogeneous results and it is unlikely that extracting data from more studies would have resulted in consensus regarding FI categorisation. An additional limitation of this systematic scoping review is that only one reviewer screened titles and abstracts.

In summary, this scoping review demonstrated that high impact studies vary in the way they categorise the FI and while there is some evidence in the community-dweller literature, FI categories have not been well validated in acute and residential aged care. For the time being, the FI should be reported as a continuous variable wherever possible. It is important to continue working towards defining frailty categories - it may be desirable for researchers to recruit only mildly frail community-dwellers for an intervention study or it may be preferable for hospital-based clinicians to provide severely frail patients with an alternative model of care to mildly frail patients. Variable, unvalidated FI categorisation impacts the ability to synthesise results and to translate findings into clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this study as no datasets were generated for analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- FI:

-

frailty index

- CFS:

-

Clinical Frailty Scale

- FWCI:

-

field-weighted citation impact

- RAC:

-

residential aged care

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- eFI:

-

electronic frailty index

References

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Limits to deficit accumulation in elderly people. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:494–6.

Searle S, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer E, et al. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8:24.

Rockwood K, Andrew M, Mitnitski A. A comparison of two approaches to measuring frailty in elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62A(7):738–43.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

What is field-weighted citation impact (FWCI)? [cited 2021 October 26]. Available from: https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/14894/kw/FWCI/supporthub/scopus/related/1/.

Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing. 2016;45:353–60.

Wallace L, Theou O, Godin J, et al. Investigation of frailty as a moderator of the relationship between neuropathology and dementia in Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the rush memory and aging project. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(2):177–84.

Rockwood K, Song X, Mitnitski A. Changes in relative fitness and frailty across the adult lifespan: evidence from the Canadian National Population Health Survey. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):E487–94.

Theou O, Brothers T, Mitnitski A, et al. Operationalization of frailty using eight commonly used scales and comparison of their ability to predict all-cause mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1537–51.

Blodgett J, Theou O, Kirkland S, et al. Frailty in NHANES: comparing the frailty index and phenotype. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60:464–70.

Hoover M, Rotermann M, Sanmartin C, et al. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep. 2013;24(9):10–7.

Thompson M, Theou O, Yu S, et al. Frailty prevalence and factors associated with the frailty phenotype and frailty index: findings from the north West Adelaide health study. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37(2):120–6.

Ntanasi E, Yannakoulia M, Kosmidis M, et al. Adherence to mediterranean diet and frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:315–22.

Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:681–7.

Ravindrarajah R, Hazra N, Hamada S, et al. Systolic blood pressure trajectory, frailty, and all-cause mortality >80 years of age. Circulation. 2017;135(24):2357–68.

Lansbury L, Roberts H, Clift E, et al. Use of the electronic frailty index to identify vulnerable patients: a pilot study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(664):e751–6.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, et al. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):766–72.

Chong E, Ho E, Baldevarona-Llego J, et al. Frailty in hospitalized older adults: comparing different frailty measures in predicting short- and long-term patient outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;18:450–7.

Joseph B, Zangbar B, Pandit V, et al. Emergency general surgery in the elderly: too old or too frail? J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:805–13.

Poudel A, Peel N, Nissen L, et al. Adverse outcomes in relation to polypharmacy in robust and frail older hospital patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(8):767.e769–13.

Singh I, Gallacher J, Davis K, et al. Predictors of adverse outcomes on an acute geriatric rehabilitation ward. Age Ageing. 2012;41:242–6.

Andrew M, Shinde V, Ye L, et al. The importance of frailty in the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization in elderly people. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:405–14.

Dent E, Chapman I, Howell S, et al. Frailty and functional decline indices predict poor outcomes in hospitalised older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:477–84.

Mueller N, Murthy S, Tainter C, et al. Can sarcopenia quantified by ultrasound of the rectus femoris muscle predict adverse outcome of surgical intensive care unit patients as well as frailty? A prospective, observational cohort study. Ann Surg. 2016;264(6):1116–24.

Zeng A, Song X, Dong J, et al. Mortality in relation to frailty in patients admitted to a specialized geriatric intensive care unit. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(12):1586–94.

Hao Q, Zhou L, Dong B, et al. The role of frailty in predicting mortality and readmission in older adults in acute care wards: a prospective study. Sci Rep. 2019;9.

Arjunan A, Peel N, Hubbard R. Gait speed and frailty status in relation to adverse outcomes in geriatric rehabiltiation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:859–64.

Theou O, Jayanama K, Fernandez-Garrido J, et al. Can a prebiotic formulation reduce frailty levels in older people? J Frailty Aging. 2018;8:48–52.

Theou O, Blodgett J, Godin J, et al. Association between sedentary time and mortality across levels of frailty. CMAJ. 2017;189(33):e1056–64.

Blodgett J, Theou O, Howlett S, et al. A frailty index from common clinical and laboratory tests predicts increased risk of death across the life course. Geroscience. 2017;39:447–55.

Shaw B, Borrel D, Sabbaghan K, et al. Relationships between orthostatic hypotension, frailty, falling and mortality in elderly care home residents. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19.

Theou O, Sluggett J, Bell J, et al. Frailty, hospitalization, and mortality in residential aged care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(8):1090–6.

Theou O, Tan E, Bells J, et al. Frailty levels in residential aged care facilities measured using the frailty index and FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:e207–12.

Maclagan L, Maxwell C, Gandhi S, et al. Frailty and potentially inappropriate medication use at nursing home transition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:2205–12.

Campitelli M, Bronskill S, Hogan D, et al. The prevalence and health consequences of frailty in a population-based older home care cohort: a comparison of different measures. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16.

Hogan D, Freiheit E, Strain L, et al. Comparing frailty measures in their ability to predict adverse outcome among older residents of assisted living. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12.

Kulminski A, Ukraintseva S, Kulminskaya I, et al. Cumulative deficits better characterize susceptibility to death in elderly people than phenotypic frailty: lessons from the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:898–903.

Buckinx F, Reginster J-Y, Gillain S, et al. Prevalence of frailty in nursing home residents according to various diagnostic tools. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6:3.

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. How might deficit accumulation give rise to frailty? J Frailty Aging. 2012;1(1):8–12.

Mitnitski A, Collerton J, Martin-Ruiz C, et al. Age-realted frailty and its association with biological markers of ageing. BMC Med. 2015;13.

Ambagtsheere R, Beilby J, Seiboth C, et al. Prevalence and associations of frailty in residents of Australian aged care facilities: findings from a retrospective cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1849–56.

Ambagtsheer R, Shafiabady N, Dent E, et al. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to identify frailty within a residential aged care administrative data set. Int J Med Inform. 2020;136.

Ge F, Liu M, Tang S, et al. Assessing frailty in Chinese nursing home older adults: a comparison between the FRAIL-NH scale and frailty index. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(3):291–8.

Stock K, Hogan D, Lapane K, et al. Antipsychotic use and hospitalization among older assisted living residents: does risk vary by frailty status? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(7):779–90.

Hubbard R, Peel N, Samanta M, et al. Frailty status at admission to hospital predicts multiple adverse outcomes. Age Ageing. 2017;46:801–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There are no funding sources to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH devised the research study. IK, NR and EG performed the systematic review and extracted data. EG analysed the data and prepared the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approvals were sought by the individual studies. No additional approval was required for this systematic scoping review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gordon, E.H., Reid, N., Khetani, I.S. et al. How frail is frail? A systematic scoping review and synthesis of high impact studies. BMC Geriatr 21, 719 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02671-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02671-3