Abstract

Background

Internationally, 2–5% of people live in residential or nursing homes, many with multi-morbidities, including severe cognitive impairment. Pain is frequently considered an expected part of old age and morbidity, and may often be either under-reported by care home residents, or go unrecognized by care staff. We conducted a systematic scoping review to explore the complexity of pain recognition, assessment and treatment for residents living in care homes, and to understand the contexts that might influence its management.

Methods

Scoping review using the methodological framework of Levac and colleagues. Articles were included if they examined pain assessment and/or management, for care or nursing home residents. We searched Medline, CINAHL, ASSIA, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar; reference lists were also screened, and website searches carried out of key organisations. Conversations with 16 local care home managers were included to gain an understanding of their perspective.

Results

Inclusion criteria were met by 109 studies. Three overarching themes were identified: Staff factors and beliefs - in relation to pain assessment and management (e.g. experience, qualifications) and beliefs and perceptions relating to pain. Pain assessment – including use of pain assessment tools and assessment/management for residents with cognitive impairment. Interventions - including efficacy/effects (pharmaceutical/non pharmaceutical), and pain training interventions and their outcomes.

Overall findings from the review indicated a lack of training and staff confidence in relation to pain assessment and management. This was particularly the case for residents with dementia.

Conclusions

Further training and detailed guidelines for the appropriate assessment and treatment of pain are required by care home staff. Professionals external to the care home environment need to be aware of the issues facing care homes staff and residents in order to target their input in the most appropriate way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Internationally, 2–5% of people live in residential or nursing care homes, with almost 60% of residents being over 85 years of age [1]; many live with multi-morbidities, including severe cognitive impairment [2]. Pain is frequently considered an expected part of old age and morbidity, and as a consequence is often under-reported by care home residents, or may go unrecognized by care staff [3].

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) [4] estimates that 20% of the adult population are living with chronic pain. They consider pain to be individual and subjective, and assert that the inability to communicate pain verbally, for example in people with dementia, does not negate the possibility of pain being present, and the need for treatment [4].

Where the presence of pain cannot be verbalized, pain behaviors may include guarding, agitation, facial expression, or altered mobility [4]. However, it is unclear how well such factors are understood and, when pain is identified as the probable cause of such behaviour, whether this is acted upon by care home staff [5]. In addition, where pain is recognized and treated, the IASP advises caution with older people, who are generally less tolerant of analgesia, and may experience side effects such as sedation or confusion if the analgesia type and dose are not chosen with care [4]. In addition, over or misprescribing may lead to drug related problems for nursing home residents [6]. Non-pharmacological treatments or adjuncts are therefore worth considering for treatment of pain in older age. In addition to such concerns, the influence of emotional state on pain is a significant factor, which is not always acknowledged [7].

While appropriate assessment of pain is an essential step to effective treatment [8], and various pain assessment tools have been developed [9], pain assessment and management in care homes is complex. To further understand these complexities, we undertook a scoping review to explore the contexts which may influence pain assessment and management for care home residents.

Methods

Review category

This scoping review was carried out using the methodological framework of Levac et al. [10] involving six stages noted in Table 1.

Review aim

The aim of the review was to summarize a range of evidence relating to the assessment and management of different types of pain experienced by frail older people living in care homes. Stakeholder opinions (care home staff/managers) were gathered to further inform evidence synthesis (Stage 6: Levac et al., 2010). Informal, face-to-face conversations with care home staff took place, to elicit their views and knowledge about pain assessment and management. These meetings were carried out as an adjunct to the scoping review (to fulfil stage 6, as indicated previously), to ascertain if local staff views shared similarities with the findings of the review, or displayed differences. The review was conducted between September 2019 and March 2020.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Key words/MeSH terms

Key words relating to pain (e.g. pain, soreness, discomfort, allodynia, neuralgia, neuritis, neuropathy, sensitivity, dysesthesia, hyperalgesia etc.), and pain assessment or management, were combined with care home terminology (residential, care, nursing, residents, patients etc.) to acknowledge the multiple terms that may be used to describe this type of care setting. Terms were combined using Boolean AND/OR strategies, to ensure the most relevant work was accessed (e.g. pain OR discomfort OR neuralgia AND care home OR residential care OR nursing home etc), as detailed in the search strategy developed by the research team (Additional file 1). Due to time and resource limitations, papers not available or translated into English language were excluded

Types of study method

All study methods, and grey literature/reports were open for inclusion; the review aimed to give a broad perspective on the topic area, rather than an in-depth analysis from a narrower viewpoint. Theses and dissertations were excluded, unless summarised into shorter papers. This approach helped to balance the need for feasibility, with breadth and comprehensiveness (Levac et al., 2010: Stage 2).

Databases

Databases searched included: Medline, CINAHL, ASSIA, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. Reference lists of relevant items were screened, and website searches carried out for key organisation reports (e.g. Age UK, The Care Quality Commission, National Care Homes Association, International Association for the Study of Pain, The British Pain Society etc.) to ensure a wide range of relevant literature was accessed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Table 2

Screening and selection methods

Two reviewers (JP & SA) blind screened papers independently at all stages of the screening process, with disagreements being resolved by further discussion. A PRISMA flow diagram was prepared detailing the selection process – see Fig. 1.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from individual studies or reports were extracted onto a pre-designed table, and cross-checked by two reviewers (JP & SA). We did not aim to produce a detailed quality appraisal of included studies or exclude studies on the grounds of quality, as per scoping review guidelines [11], but noted any quality limitations to further inform the review.

Analysis methods

We conducted a thematic analysis of the papers reviewed, and an analysis of stakeholder findings from 16 care homes. We sought to identify commonalities across studies and group these into areas of shared interest. To assist in this process, we used mind mapping [12, 13], in order to interpret and display associations between individual findings, and to identify common themes across studies. This approach was chosen because, with regard to analysing and improving health provision, there often needs to be “quite specific feedback about what works, where improvements can be made and what barriers there may be to accessing services. This type of feedback can be clearly represented in a mind map” [13].

Two researchers (JP, ASAVM) carried out an initial grouping, which was then discussed and amended with other team members, until agreement was reached. In particular, all data were examined to identify organisational factors, such as internal and external barriers or facilitators that might either help or hinder pain assessment and management. Links and implications for policy, practice and research were sought within the analysis process (Levac et al., 2010: Stage 5).

Results

Overview

One hundred nine studies were found that fulfilled all inclusion criteria. An overview of these studies is presented in Additional file 2. Due to the large number of studies, each tabulated ‘included study’ (IncS) was allocated a number (e.g. IncS [32, 33] etc) for identification within the following text. Full references details for included studies are presented below the main reference list.

There was a diverse geographical spread across 17 countries, indicating global interest and potential concern about the issues surrounding pain assessment and management in care homes.

Methods and appraisal of included studies

Research methods used were diverse, including 13 RCTs, 18 non-randomised trials (typically pre/post-test studies), 16 qualitative studies, 30 of cross-sectional design, and 13 systematic reviews. Where studies were longitudinal (mainly RCTs) the longest duration of follow up was 6 months. While the majority of studies clearly detailed the methods used, study limitations largely related to methodological issues (e.g. cross sectional design) or small participant numbers. The difficulties inherent in including care home participants in reseach, who by the nature of their situation are vulnerable, was not widely acknowledged.

Analysis

Our analysis provided a breakdown of topics of interest across and between studies, and revealed six initial themes:

-

Staff factors in relation to pain assessment and management (e.g. experience, qualifications etc.)

-

Beliefs and perceptions relating to pain (staff, residents, relatives)

-

Pain assessment tools

-

Pain assessment and management for nursing care home residents with cognitive impairment

-

Pain intervention efficacy/effects (pharmaceutical/non pharmaceutical)

-

Pain training interventions and their outcomes

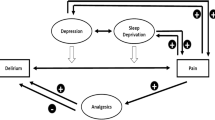

These six themes were further amalgamated into three broader overarching themes or categories: Staff factors and beliefs, Pain assessment, and Interventions, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Due to some studies being multifaceted, results from a particular study may appear in more than one category.

Staff factors and beliefs

There were a number of included papers (n = 17) that explored the training level and experience of health care staff, and the impact this had on pain recognition and practices relating to pain management.

For example, Takai et al. (IncS [125]) reported a relationship between increased nursing experience and lower pain prevalence in residents, and a relationship between the years of staff experience and the utilization of non-drug methods to treat it, being more frequently used by those with greater pain experience and training (IncS [126]).

Experience tended to affect judgements: Alm & Norbergh (IncS [34]) found that nurses with less experience had less confidence in making a judgement about pain themselves; however Baeza et al. (IncS [37]) reported that care home staff with more experience tended to feel more stressed when not knowing the cause of pain for residents with dementia, and thereby less able to make their own judgement.

One systematic review (IncS [36]) reported a correlation between less experienced staff and the verbally disruptive behaviour of residents, which may have been a manifestation of untreated pain.

Findings were also reported relating to staff turnover, type of working contract, and relationships with pain assessment and management, with evidence that pain assessment and management was performed better when there was lower staff turnover, and staff were hired permanently, and had longer tenure time (IncS [36, 47, 60, 70]).

Care homes where staff had higher qualifications appeared to perform better in pain assessment and management, and give better quality of care (IncS [45, 46, 100]). In addition, while some GPs lacked knowledge about pain assessment themselves, they valued the role of nurses and other caregivers (IncS [84]), even although some staff perceived GPs as disinterested in relation to pain (IncS [109]).

Care home staffs’ beliefs and perceptions exerted an influence on pain management, as examined in 40 of the included papers. For example, several papers reported that when staff felt more confident about the identification of pain, they were more certain in relation to its management (IncS [42, 75, 93]). However, when staff considered pain to be part of ageing, they were less likely to identify pain in a resident (IncS [93]). It was also reported that those residents who thought that pain was part of getting older were influenced by staff attitudes towards treatment, potentially resulting in reduced therapy options (IncS [135]).

There was evidence that many staff did not agree with the statement that pain is part of aging and cannot be treated (IncS [39]); however, with regard to residents with dementia, 50% of staff did consider pain as part of aging in this population (IncS [45]).

When exploring nurses’ knowledge and attitudes to pain assessment in people with dementia, Burns & McIfatrick (IncS [44]) reported that even amongst those with very recent training in pain assessment, it was still considered to be a “guessing game”; such beliefs had the potential to result in a higher prevalence of untreated pain in residents with dementia (IncS [125]). However, when staff were familiar with residents, they found it easier to interpret non-verbal cues of pain (IncS [80, 92, 99, 135]), and potentially differentiate it from other forms of distress (e.g. emotional distress).

Staff beliefs and concerns about the safety of using opioid analgesic were highlighted in several studies (IncS [40, 45, 84, 90, 107). These concerns related to either addiction beliefs, or fears about increased confusion and sedation; drug utilization was also reduced when either nurses or residents refused to use or take certain medications, even when their use may have been benefical.

There were some findings relating to staff perceptions about why residents might not report pain: for example in one paper it was suggested that staff were unsure if residents were displaying pill-seeking behavior because they wanted attention, rather than being truly in pain (IncS [61]). In other papers, it was felt that residents might not be reporting pain because they were concerned about potential loss of independence (IncS [92, 107]) or did not want to be seen as complainers or difficult residents (IncS [90, 92, 135]).

There was some evidence from relatives that related to the approaches of staff to pain management, and also relatives’ feelings of being involved in the care of their family member. For example, Barry et al. (IncS [38]) found that relatives who visited care homes more often considered that pain was being noted and treated to a greater extent by the staff. Also, relatives visiting their relatives frequently were more likely to interpret (and report to staff) behavior changes as signs of pain (IncS [68]), and thereby felt more actively involved in their care (IncS [55, 90]).

Pain assessment

Of the included studies, 16 examined the use of pain assessment tools; in general these did not appear to be widely utilized (IncS [41, 62, 83]), with some GPs in particular having little knowledge of specific tools to assess pain in care home residents (IncS [84]). In one of these studies, detailing results from 810 participants across 7 European counries, it was reported that 58% of staff did not use any tool to assess pain in their daily practice (IncS [139]). In other studies, although staff had knowledge of the tools, they reported problems interpreting them (IncS [128, 140]), or felt them to be time consuming (IncS [73, 110, 115]), However, when staff were trained in the utilization of tools, their use was more likely (IncS [128]), and with increased usage, staff appeared to recognise their value to a greater extent (IncS [103]).

The impact on residents of tool usage was highlighted in several studies. For example, the proportion of residents with pain appeared to increase, because pain questions were being asked (and recorded) more frequently, and also pain was being treated to a greater extent (IncS [105, 114]). The use of tools was considered to increase awareness, and render staff more sensitive and responsive to residents’ pain-related behaviour (IncS [100]).

The most commonly researched tool in the included studies was the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia scale (PAINAD). Where used, pain assessment tools that were found to be helpful included the Pain Assessment Checklist for seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC), DOLOPLUS-2, Pain Assessment in Non-Communicative Elderly Persons (PAINE), and the Pain Assessment for the Dementing Elderly (PADE). In contrast, the Abbey Pain Scale, while commonly used in practice, was found to be inaccurate when assessing pain intensity compared with staff-estimated pain intensity, and it was also considered to be lacking in direction about precision of usage (IncS [125]).

Interventions

Of the 22 studies examining pain treatment interventions, most were shown to produce effective results. Where pain management practice improvements were made, analgesic and non-pharmaceutical treatment use increased and pain scores were shown to reduce (e.g. IncS [50, 67, 118]). However, a systematic review (IncS [120]) reported that pain scores deteriorated (increased) where there was a high turnover of staff, and lack of physician support.

Over half of the pain intervention studies (n = 13) were related to non-pharmaceutical treatments, and many indicated that alternative therapies had the potential to be effective (IncS [51, 59, 69, 93, 132]). Non-pharmaceutical treatments, which included massage, aromatherapy, exercise, psychological support, and humour therapy, were viewed favourably by staff (IncS [32]), but not necessarily by relatives (IncS [32, 110]). Managerial support and staff training for non-pharmaceutical treatments were seen as necessary to facilitate usage (IncS [32, 73, 91]). However, a large study by Lukas et al. (IncS [102]; participant n = 1900) indicated that moderate to severe pain was more likely to be treated by pharmaceutical means, and less likely to be treated with non-pharmaceutical or alternative therapies.

Among the 21 included papers that considered pain management for care home residents with cognitive and/or communication impairment, there was general acknowledgement that the recognition of pain was challenging (IncS [33, 37, 45, 39]). There was also recognition that these residents’ pain may be less well treated (IncS [66, 75, 106]), especially where cognitive impairment was more severe (IncS [66]). A lack of staff knowledge (IncS [40]), inadequate assessment (IncS [58, 77, 106, 108]), or availability and appropriateness of pain education programmes were influencing factors (IncS [45, 55]). However, training programmes, as further detailed below, could help to increase awareness (IncS [71, 74, 115]), as well as improving recognition of behavioural and non-specific manifestations of pain for people with cognitive impairment (IncS [99]).

Pain training interventions were examined in 21 papers, and were shown to have the potential to be effective in improving pain management and treatment use/appropriateness (IncS [50, 63, 64, 70, 71, 74, 94, 110, 115, 118, 128]). As well as improved pain management, resident quality of care and quality of life also had the potential to be enhanced (IncS [44]), which could have an impact on their longer term wellbeing.

There was some suggestion that increasing staff knowledge regarding pain management could reduce anti-psychotic drug use (IncS [48]). Training was also helpful in the use of non-pharmaceutical treatments (IncS [50, 110]), helping to improve staff awareness and confidence (IncS [133]). There were also indications that training for non-registered care staff might be beneficial (IncS [82, 127]).

Consultation with stakeholders

In addition to the scoping review findings, visits to 16 care homes across one region in SE Scotland took place. Staff were unaware of the findings from the literature review. However, these conversations confirmed many points from the literature, with all care home managers expressing the need to improve pain assessment and management. Three quarters of the care homes had registered nurses on-site. Most care home managers recognised the presence of pain in the majority of their residents. One care home, where all residents had a diagnosis of dementia, had all residents on regular paracetamol. There was, however, an overall lack of knowledge about identifying and systematically treating pain, and a reluctance to use pain assessment tools; where they were used, the tools of choice were the Abbey pain scale and Doloplus2. The main barrier to their completion appeared to be a lack of knowledge about them, with staff saying “we just have to ‘pick it up’ from other staff”.

Distressed behaviour in residents with advanced dementia appeared to be more attributed to the condition rather than the possibility of the presence of pain. While a wide variety of pain medication was used (e.g. non-opioids, anti-inflammatories, and opioids), there was still some expressed concern about over-dosage. Nonpharmacological interventions were used, but only to a limited extent, and not at all in some care homes. The majority of staff had received no pain training. Where training was in place, it appeared to be on-line rather than face-to-face, limiting discussions with peers about experiences. Nonetheless, there was a desire to improve, although current external support systems did not appear to be very responsive with offering support.

Findings from the field research carried out at the care homes is summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

This review has examined evidence relating to pain relief in care homes, and sought to understand contexts that might influence the assessment and management of pain for residents. As such, it fulfils the requirement of a scoping review to map the current state of evidence, rather than produce a detailed critical appraisal [11]. To our knowledge, such a broad scoping review has not been previously undertaken.

By including multiple research designs and methods, the review gives a comprehensive overview of findings from a diverse range of research studies. It updates, incorporates, and broadens the focus of the 13 included reviews, which examined narrower perspectives (e.g. management of specific types of pain, such as musculo-skeletal: IncS [65]; or cancer-related pain: IncS [121]; and reviews specific to dementia: IncS [35, 81, 107, 121]).

Care home staff knowledge and training (or lack of it) occurred as a common thread across the different themes identified in the review. It was clear that training staff in the assessment and management of pain, and training in the use of appropriate pain assessment tools, in addition to experience and knowledge of residents, did reap benefits for residents in terms of greater comfort and quality of life, and helped staff to identify treatment options. However, a report by the International Longevity Centre (ILC) [14] argues that a lack of funding for training above and beyond essential or mandatory training exists. It is unclear what regulatory bodies for care homes in other countries (if in existence) advise; however, in the UK, recent reports published by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) show little or no focus on pain [15]. Where training does take place, it is often focussed on the need to fulfil other mandatory CQC requirements, rather than a commitment towards workforce development [14]. Prescribing for older people generally is recognised as complex, and staff education is essential to improve outcomes [16]. Due to budget limitations, such training may need to be funded by external sources, in the interest of resident well-being, staff satisfaction, and overall care home performance. Areas that would benefit from training programmes for care home staff are summarised in Table 4.

Lack of training may account for reduced staff knowledge and/or concerns about the use of opioids for older people. The differing views of experts may add to this confusion: according to Guerriero [17], guidelines should recommend opioid use as a first line treatment for moderate to severe persistent pain in older adults, whereas the American Geriatrics Society [18] advise more caution due to the potential side effects (disorientation, potential respiratory suppression, constipation etc). The World Health Organisation (WHO) pain ladder, which advocates stepping up to opiod use if pain is not controlled, has not been validated for non-cancer chronic pain [19], and may contribute to inappropriate prescribing if used in non-cancer pain [19]. However, current NICE guidance [20] does not rule out opioid use if other drugs prove ineffective, and also advocates the use of non-pharmaceutical treatments to augment or compliment medication. More detailed guidance is clearly needed for staff involved in the care of older people with chronic pain, and may assist staff decision-making.

With further regard to staff training, Wright [21] argues for care assistants to have greater access to training, considering it a key factor in attracting and retaining suitable employees. This is consistent with WHO guidelines relating to health staff retention [22], which state that financial incentives alone are insufficient to retain staff. Frogner & Spetz [23] also take up the theme that improved education and training for staff, alongside higher wages, and higher overall staffing levels, are necessary to combat and lower staff exit rates. The high turnover of staff in care homes has been called the ‘elephant in the room’ by Wilson [24], given that approximately 25% of staff leave in any one year [14]. This makes sustainability of any improvement in the assessment and management of pain less likely, unless there is regional support for training and retention.

Unfortunately, working in the care home sector may not viewed as a career choice for many qualified nurses, even though there are many more beds in nursing homes than in acute care hospitals, and the care needs of residents are increasingly complex [25, 26]. Whilst the difficulty of recruitment and high turnover of staff is therefore frequently acknowledged as problematic, the evidence from this review shows a correlation between high turnover of staff and less well controlled pain; this would appear to contravene a duty of care. It has also been suggested that older people cared for at home may have less pain and greater comfort than those being cared for in care homes [27].

On a more positive note, this review has also highlighted that more experienced staff, familiar with their residents, are more likely to include non-pharmaceutical measures in the management of pain (IncS [34, 51, 59, 67, 93, 132]). That said, the use and effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical treatments can be aided by appropriate assessment prior to, and following, interventions.

It is evident that in order to overcome barriers relating to pain assessment, such as the use of tools to augment observational judgment, the mechanisms by which the integration of new practice occurs, need to be understood to a greater extent [28]. If staff can see the value and rewards associated with using a pain assessment and management framework (e.g. increased resident comfort), then shifts in attitudes and norms can occur more readily [28]. Pain in frail older people needs to become part of the regulation of care homes, although it has been argued that this may not happen until care homes adopt an electronic minimum data set or equivalent tool [29]; this has gained more interest recently, stimulated by conversations as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic [30].

Further points of relevance highlighted by the review include the need for clear communication and support from external professionals, including greater access to GPs, and the value of including the views of relatives regarding the detection of pain.

It could be argued that highlighting the skill required to deliver quality care to residents, and the importance of good pain assessment/management, may help to attract nurses and care staff into a career with frail older people in care homes. The value placed on such care by the public and politicians has certainly been highlighted during the COVID19 pandemic [31], and may provide a timely platform from which to launch recruitment drives.

Review strengths and limitations

It is acknowledged that the review may not have captured all relevant material. Searches, screening, and study selection are all open to error or bias. However, the rigorous methods utilised, including blind screening and cross-checking, have served to minimise these limitations. The broad nature of the review, including seeking care home staff opinions, has enabled an expansive view of the available knowledge, rather than a narrower or confined perspective. With such a large volume of evidence being included in the reveiw, we acknowledge that another research team may have chosen to emphasise other areas within the included research. However, seeking the views of local care home staff did serve to validate the findings, and their interpretation, in this review.

Conclusions

This review has highlighted that training and explicit guidelines for the appropriate assessment and treatment of pain remain a current requirement for care home staff. Knowledge of the issues that face care home staff and their residents can help other professionals, external to the care home environment, to target their input in the most appropriate way. Internal and external contexts need further examination in order to co-create a framework that integrates the assessment of pain and its management, to the benefit of patients.

In essence, there is a need for pain assessment and management training for all staff in care homes, including training relating to residents with dementia. Raising the importance of good pain assessment and management may alter staff perceptions relating to the presence of pain in older people, particularly those with cognitive impairment.

Increasing staff knowledge regarding pain management may reduce anti-psychotic drug use, and increase the use of non-pharmaceutical treatments.

The use of tools may also help to increase awareness, and render staff more sensitive and responsive to residents’ pain-related behaviour. However, pain assessment and its management may not improve in care homes if there remains a high turnover of staff. In addition, clear communication between care home staff and both relatives and external professionals is essential to promote identification of pain and its management.

Availability of data and materials

Further data and a fuller report on this review are available on request from the authors.

Change history

22 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02413-5

References

Office for National Statistics. Changes in the older resident care home population between 2001 and 2011 (online). UK, Office for National Statistics 2014. www.ons.gov.uk. (Accessed 30 July 2019).

Alzheimer's Society. Low expectations: attitudes on choice, care and community for people with dementia in care homes. London: Alzheimer's Society; 2013.

Davies J, Cotton S. The assessment of pain in older people: UK National Guidelines. Age Ageing. 2018;47:i1–i22.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Pain terms. IASP (online). 2017. www.iasp-pain.org. (Accessed 30 July 2019).

Reid M, O'Neil K, Dancy J, Berry C, Stowell S. Pain management in long-term care communities: a quality improvement initiative. Ann Longterm Care. 2015;23:29–35.

Fog AF, Mdala I, Engedal K, Straand J. Variation between nursing homes in drug use and in drug-related problems. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01745-y.

British Pain Society (BPS). What is pain? London, BPS 2014.

Schofield P. The assessment of pain in older people: UK national guidelines. Age Ageing. 2018;47(suppl_1):i1–i22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx192.

Chow W, Chow R. Lam M, Rowbottom L, Hollenberg D, Friesen E. pain assessment tools for older adults with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Neurodegen Dis Manage. 2016;6(6):525–38. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt-2016-0033.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69–78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143–52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Buzan T. Use your head. London: BBC Books; 1974.

Burgess-Allen J, Owen-Smith V. Using mind mapping techniques for rapid qualitative data analysis in public participation processes. Health Expect. 2010;13(4):406–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00594.x.

International Longevity Centre (ILC). We "dare to care". Care homes and nursing at the frontline of our response to aging. London, International Longevity Centre 2017.

Care Quality Commission. Care Quality Commission (online). 2020. www.cqc.org.uk. (Accessed 13 February 2020).

Loganathan M, Singh S, Franklin BD, Bottle A, Majeed A. Interventions to optimise prescribing in care homes: systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):150–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq161.

Guerriero F. Guidance on opioids prescribing for the management of persistent non-cancer pain in older adults. World Journal of Clinical Cases. 2017;5(3):73–81. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i3.73.

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13702.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Prescribing in the elderly. NICE, UK. 2019. www.nice.org.uk/guidance. (Accessed%2022/09/20).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Prescribing in the elderly. NICE, UK. 2020. www.nice.org.uk/guidance. (Accessed 22/09/20).

Wright E. We must value healthcare assistants by investing in their education and training. (online). Nursing Times. 2018. www.nursingtimes.net/opinion. 2018. (Accessed 1 August 2019).

World Health Organisation (WHO). Guidelines: incentives for health professionals. Geneva: World Health Organisation 2009.

Frogner B, Spetz J. Entry and exit of workers in long term care. Health Workforce Research Center on Long Term Care. California: University of San Francisco; 2015.

Wilson J. The elephant in the room: staff turnover. USA: Relias; 2017. (blogg; accessed 6 February 2020)

Iliffe S, Davies S, Gordon A, Scneider J, Dening T, Bowman C. Provision of NHS generalist and specialist services to care homes in England: review of surveys. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17(02):122–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423615000250.

Spilsbury K, Hanratty B, McCaughan D. Supporting nursing in care homes. UK: University of Leeds; 2015.

Xu Y, Jiang N, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Chen L, Ma S. Pain perception of older adults in nursing home and home care settings: evidence from China. BMC Geriatriatrics. 2018;18(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0841-0.

Brewster A, Curry L, Cherlin E, Talbert-Slagle K, Horwitz L, Bradley E. Integrating new practices: a qualitative study of how hospital innovations become routine. Implement Sci. 2015;10:e1–12.

Carpenter I, Stosz L. Developing the use of 'MDS-RAI' reports for UK care homes. UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2008.

Burton J, Goodman C, Quinn T. The invisibility of the UK care home population – UK care homes and a minimum dataset. UK: International Longterm Care Policy Network; 2020.

Bailey S, West M. Covid-19: why compassionate leadership matters in a crisis. London: The King’s Fund; 2020.

Supplementary file references

ABRAHAMSON K, DECRANE S, MUELLER C, DAVILA H, ARLING G. Implementation of a nursing home quality improvement project to reduce resident pain: a qualitative case study. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30(3):261–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000099.

AHN H, GARVAN C, LYON D. Pain and aggression in nursing home residents with dementia: minimum data set 3.0 analysis. Nurs Res. 2015;64(4):256–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000099.

ALM A, NORBERGH K. Nurses' opinions of pain and the assessed need for pain medication for the elderly. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(2):e31–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2010.07.007.

ALONSO-FERNANDEZ M, LOPEZ-LOPEZ A, LOSADA A, GONZALEZ J, WETHERELL J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and selective optimization with compensation for older people with chronic pain: A pilot study. Pain Med. 2013;17:264–77.

ANDERSON K, BIRD M, MACPHERSON S, BLAIR A. How do staff influence the quality of long-term dementia care and the lives of residents? A systematic review of the evidence. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(8):1263–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000570.

BAEZA R, TORRUBIA R, ANDION O, LONCAN P, MALOUF J, BANOS J. El dolor en ancianos y en pacientes con deficits cognitivos. Un estudio DELPHI Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2018;25.

BARRY H, PARSONS C, PASSMORE P, HUGHES C. Pain in care home residents with dementia: an exploration of frequency, prescribing and relatives' perspectives. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):55–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4111.

BARRY H, PARSONS C, PASSMORE P, HUGHES C. Exploring community pharmacists' experiences with and attitudes towards people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(10):1077–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3931.

BARRY H, C., P., PETER PASSMORE, A. & HUGHES, J. An exploration of nursing home managers' knowledge of and attitudes towards the management of pain in residents with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(12):1258–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3770.

BEN NATAN, M., ATANELI, M., ADMENKO, A. & HAR NOY, R. Nurse assessment of residents' pain in a long-term care facility. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60:251–7.

BIRD M, ANDERSON K, MACPHERSON S, BLAIR A. Do interventions with staff in long-term residential facilities improve quality of care or quality for life people with dementia? A systematic review of the evidence. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(12):1937–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001083.

BOERLANGE A, MASMAN A, HAGOORT J, TIBBOEL D, BAAR F, VAN DIJK M. Is pain assessment feasible as a performance Indicator for Dutch nursing homes? A cross-sectional approach. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(1):36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2010.05.003.

BURNS M, MCIFATRICK S. Palliative care in dementia: literature review of nurses' knowledge and attitudes towards pain assessment. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015a;21(8):400–7. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.8.400.

BURNS M, MCIFATRICK S. Nurses' knowledge and attitudes towards pain assessment for people with dementia in a nursing home setting. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015b;21(10):479–87. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.10.479.

CASTLE N, FURNIER J, FERGUSON-ROME J, OLSON D, JOHS-ARTISENSI J. Quality of care and long-term care administrators’ education: does it make a difference? Health Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(1):35–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000007.

CASTLE N, ANDERSON R. Caregiver staffing in nursing homes and their influence on quality of care: using dynamic panel estimation methods. Med Care. 2011;49:542–52.

CERVO F, BRUCKENTHAL P, FIELDS S, BRIGHT-LONG L, CHEN J, ZHANG G, et al. The role of the CNA pain assessment tool [CPAT] in the pain Management of Nursing Home Residents with dementia. Geriatr Nurs. 2012;33(6):430–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.04.001.

CHANG E, JOHNSON A, HARRISON K, EASTERBROOK S, BIDEWELL J, STEWART H, et al. Challenges for professional care of advanced dementia. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;15:41–7.

CHEN, Y. & LIN., L. 2016. Ability of the pain recognition and treatment [PRT] protocol to reduce expressions of pain among institutionalized residents with dementia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Pain Manag Nurs, 17, 14–24.

CINO, K. 2014. Aromatherapy hand massage for older adults with chronic pain living in long-term care. J Holist Nurs, 32, 304–313, 4, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010114528378.

COHEN-MANSFIELD J, DAKHEEL-ALI M, MARX M, THEIN K, REGIER N. Which unmet needs contribute to behavior problems in persons with advanced dementia? Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(1):59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043.

COHEN-MANSFIELD J, THEIN K, MARX M. Predictors of the impact of nonpharmacologic interventions for agitation in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(07):e666–71. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08649.

CORAZZINI K, MCCONNELL E, ANDERSON R, REED D, CHAMPANE M, LEKAN D, et al. The importance of organizational climate to training needs and outcomes in long-term care. Alzheimer's Care Today. 2010;11:109–21.

CORBETT A, NUNEZ K, SMEATON E, TESTAD I, THOMAS A, CLOSS J, et al. The landscape of pain management in people with dementia living in care homes: A mixed methods study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1354–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4445.

CRANLEY L, NORTON P, CUMMINGS G, BARNARD D, BATRA-GARGA N, ESTABROOKS C. Identifying resident care areas for a quality improvement intervention in long-term care: a collaborative approach. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:1–5.

DAMSGARD E, SOLGARD H, JOHANNESSEN K, WENNEVOLD K, KVARSTEIN G, PETTERSEN G, et al. Understanding pain and pain Management in Elderly Nursing Home Patients Applying an Interprofessional learning activity in health care students: A Norwegian pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(5):516–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2018.02.064.

DE SOUTO BARRETO P, LAPEYRE-MESTRE M, VELLAS B, ROLLAND Y. Potential underuse of analgesics for recognized pain in nursing home residents with dementia: A cross-sectional study. Pain. 2013;154:2427–31.

DECKER S, WARDELL D, CRON S. Using a healing touch intervention in older adults with persistent pain: A feasibility study. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(3):205–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010112440884.

DECKER F, CASTLE N. Relationship of the job tenure of nursing home top management to the prevalence of pressure ulcers, pain, and physical restraint use. J Appl Gerontol. 2010;30:539–61.

DOBBS D, BAKER T, CARRION I, VONGXAIBURANA E, HYER K. Certified nursing assistants' perspectives of nursing home residents' pain experience: communication patterns, cultural context, and the role of empathy. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(1):87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2012.06.008.

DOCKERTY T, SMITH T. Survey of current practices in pain and symptom management and research for the very elderly living in care homes journal of physiotherapy pain association, 2016, 10–16; 2016.

DOUGLAS C, HAYDON D, WOLLIN J. Supporting staff to identify residents in pain: a controlled pretest-posttest study in residential aged care. Pain Manag Nurs. 2016;17(1):25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.08.001.

DRAGER D, BUDNICK A, KUHNERT R, KALINOWSKI S, KONNER F, KREUTZ R. Pain management intervention targeting nursing staff and general practitioners: pain intensity, consequences and clinical relevance for nursing home residents. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(10):1534–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12924.

DRAGERSET, J., CORBETT, A., SELLBAEK, G. & HUSEBO, B. 2014. Cancer-related pain and symptoms among nursing home residents: a systematic review. J pain symptom manage, 48, 699-710e.1.

DUBE CE, MACK DS, HUNNICUTT JN, LAPANE KL. Cognitive impairment and pain among nursing home residents with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1509–18.

ELLIS J, WELLS Y, ONG J. Non-pharmacological approaches to pain management in residential aged care: a pre-post-test study. Clin Gerontol. 2019;42(3):286–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1399189.

ERITZ H, HADJISTAVROPOULOS T. Do informal caregivers consider nonverbal behavior when they assess pain in people with severe dementia? J Pain. 2011;12(3):331–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.012.

ERSEK M, NERADILEK M, HERR K, JABLONSKI A, POLISSAR N, DU PEN A. Pain management algorithms for implementing best practices in nursing homes: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(4):348–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.001.

ERSEK M, JABLONSKI A. A mixed-methods approach to investigating the adoption of evidence-based pain practices in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(7):52–60. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20140311-01.

FINE P, BRADSHAW D, COHEN M, CONNOR S, DONALDSON G, GHARIBO C, et al. Evaluation of the performance improvement CME paradigm for pain management in the long-term care setting. Pain Med. 2014;15(3):403–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12339.

FLAIG T, BUDNICK A, KUHNERT R, KREUTZ R, DRAGER D. Physician contacts and their influence on the appropriateness of pain medication in nursing home residents: A cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):834–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.05.014.

GAGNON M, HADJISTAVROPOULOS T, WILLAMS J. Development and mixed-methods evaluation of a pain assessment video training program for long-term care staff. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(6):307–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/659320.

GHANDEHARI O, HADJISTAVROPOULOS T, WILLIAMS J, THORPE L, ALFANO D, DAL BELLO-HAAS, V., MALLOY, D., MARTIN, R., RAHAMAN, O., ZWAKHALEN, S., CARLETON, R., HUNTER, P. & LIX, L. A controlled investigation of continuing pain education for long-term care staff. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(1):11–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/395481.

GILMORE-BYKOVSKYI A, BOWERS B. Understanding Nurses' decisions to treat pain in nursing home residents with dementia. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2013;2013:2.

GRIFFOEN C, WILLEMS E, KOUWENHOVEN S, CALJOUW M, ACHTERBERG W. Physicians' knowledge of and attitudes toward use of opioids in long-term care facilities. Pain Pract. 2017;17(5):625–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12492.

GROPELLI T, SHARER J. Nurses' perceptions of pain Management in Older Adults. Medsurg Nurs. 2013;22(6):375–82.

GUDMANNSDOTTIR G, HALLDORSDOTTIR S. Primacy of existential pain and suffering in residents in chronic pain in nursing homes: a phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(2):317–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00625.x.

GUION, V., DE SOUTO BARRETO, P., SOURDET, S. & ROLLAND, Y. 2018. Effect of an educational and organizational intervention on pain in nursing home residents: A nonrandomized controlled trial. J am med Dir Assoc, 19, 1118-1123.e2.

HOLLOWAY K, MCCONIGLEY R. Understanding nursing Assistants' experiences of caring for older people in pain: the Australian experience. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10(2):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2008.10.001.

HUSEBO B, ACHTERBERG W, FLO E. Identifying and managing pain in people with Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia: A systematic review. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(6):481–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-016-0342-7.

HYER K, KEEFE F, BROWN L, KROK J, VONGXAIBURANA E, AKINS M. Pain coping skills training for nursing home residents with pain. Best Pract Ment Health. 2010;6.

JABLONSKI A, ERSEK M. Nursing home staff adherence to evidence-based pain management practices. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(7):28–37. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20090428-03.

JENNINGS A, LINEHAN M, FOLEY T. The knowledge and attitudes of general practitioners to the assessment and management of pain in people with dementia. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0853-z.

JORDAN S, GABE-WALTERS M, WATKINS A, HUMPHREYS I, NEWSON L, SNELGROVE S, et al. Nurse-led Medicines' monitoring for patients with dementia in care homes: a pragmatic cohort stepped wedge cluster randomised trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140203.

JORDAN S, REGNARD C, O'BRIEN J, HUGHES J. Pain and distress in advanced dementia: choosing the right tools for the job. Palliat Med. 2011;26:873–8.

JORDAN A, HUGHES J, PAKRESI M, HEPBURN S, O'BRIEN J. The utility of PAINAD in assessing pain in a UK population with severe dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;26:118–26.

KAASALAINEN R, PLOEG R, DONALD F, COKER E, BRAZIL K, MARTIN-MISENER R, et al. Positioning clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners as change champions to implement a pain protocol in long-term care. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(2):78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2014.04.002.

KAASALAINEN R, BRAZIL K, AKHTAR-DANESH N, COKER E, PLOEG R, DONALD F, et al. The evaluation of an interdisciplinary pain protocol in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:664e1–8.

KAASALAINEN R, BRAZIL K, COKER E, PLOEG R, MARTIN-MISENER R, DONALD F, et al. An action-based approach to improving pain management in long-term care Can J Aging. 2010:29.

KALINOWSKI S, BUDNICK A, KUHNERT R, KONNER F, KISSEL-KROLL A, KREUTZ R, et al. Nonpharmacologic pain management interventions in German nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):464–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.002.

KNOPP-SIHOTA J, DIRK K, RACHOR G. Factors associated with pain assessment for nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(7):884–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.156.

KNOPP-SIHOTA, J., PATEL, P. & ESTABROOKS, C. 2016. Interventions for the treatment of pain in nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J am med Dir Assoc, 17, 1163.e19-1163e.28.

KONNER F, BUDNICK A, KUHNERT R, WULFF I, KALINOWSKI S, MARTUS P, et al. Interventions to address deficits of pharmacological pain management in nursing home residents--A cluster-randomized trial. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(9):1331–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.663.

LAPANE K, QUILIAM B, CHOW W, KIM M. Impact of revisions to the F-tag 309 surveyors' interpretive guidelines on pain management among nursing home residents. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(5):385–93. https://doi.org/10.2165/11599340-000000000-00000.

LAUTENBACHER S, SAMPSON E, PAHL S, KUNZ M. Which facial descriptors do care home nurses use to infer whether a person with dementia is in pain? Pain Med. 2017;18(11):2105–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnw281.

LEONE A, STANDOLI F, HIRTH V. Implementing a pain management program in a long-term care facility using a quality improvement approach. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(1):67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.003.

LIU J, LAI C. Implementation of observational pain management protocol for residents with dementia: A cluster-RCT. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):e56–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14763.

LIU, J. 2013. Exploring nursing assistants' roles in the process of pain management for cognitively impaired nursing home residents: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs, 70, 1065–1077.

LIU J, PANG P, LO, S. Development and implementation of an observational pain assessment protocol in a nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(11-12):1789–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04152.x.

LIU J, BRIGGS M, CLOSS J. Acceptability of pain behaviour observational methods [PBOMs] for use by nursing home staff. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(13-14):2071–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03671.x.

LUKAS A, MAYER B, FIALOVA D, TOPINKOVA E, GINDIN J, ONDER G, et al. Treatment of pain in European nursing homes: results from the services and health for elderly in long TERm care [SHELTER] study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):821–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.04.009.

MAMHIDIR A, SJOLUND B, FLACKMAN B, WIMO A, SKOLDUNGER A, ENGSTROM M. Systematic pain assessment in nursing homes: a cluster-randomized trial using mixed-methods approach. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1–16.

MONROE T, MISRA S, HABERMANN R, DIETRICH M, BRUEHL S, COWAN R, et al. Specific physician orders improve pain detection and pain reports in nursing home residents: preliminary data. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015a;16(5):770–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.06.002.

MONROE T, PARISH A, MION L. Decision factors nurses use to assess pain in nursing home residents with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015b;29(5):316–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.007.

NAKASHIMA T, YOUNG Y, HSU W. Do nursing home residents with dementia receive pain interventions? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2019;34(3):193–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317519840506.

NEWTON P, REEVES R, WEST E, SCHOFIELD P. Patient-centred assessment and management of pain for older adults with dementia in care home and acute settings. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2014;24(2):139–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959259814000057.

OSTERBRINK J, BAUER Z, MITTERLEHNER B, GNASS I, KUTSCHAR P. Adherence of pain assessment to the German national standard for pain management in 12 nursing homes. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(3):133–40. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/785765.

PEISAH C, WEAVER J, WONG L, STRUKOVSKI J. Silent and suffering: a pilot study exploring gaps between theory and practice in pain management for people with severe dementia in residential aged care facilities. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;15:1767–74.

PETYAEVA A, KAJANDER M, LAWRENCE V, CLIFTON L, THOMAS A, BALLARD C, et al. Feasibility of a staff training and support programme to improve pain assessment and management in people with dementia living in care homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(1):221–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4727.

PIEPER M, VAN DER STEEN J, FRANCKE A, SCHERDER E, TWISK J, ACHTERBERG W. Effects on pain of a stepwise multidisciplinary intervention [STA OP!] that targets pain and behavior in advanced dementia: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2018;32(3):682–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316689237.

PIEPER M, VAN DALEN-KOK, A., FRANCKE, A., VAN DER STEEN, J., SCHERDER, E., HUSEBO, B. & ACHTERBERG, W. Interventions targeting pain or behaviour in dementia: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):1042–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.002.

RABABA, M. 2018. The association of nurses' assessment and certainty to pain management and outcomes for nursing home residents in Jordan. Geiatr Nurs, 39, 66–71.

REID M, O'NEIL K, DANCY J, BERRY C, STOWELL S. Pain Management in Long-Term Care Communities: A quality improvement initiative. Ann Longterm Care. 2015;23(2):29–35.

RODRIGUEZ V, REINHARDT J, SPINNER R, BLAKE S. Developing a training for certified nursing assistants to recognize, communicate, and document discomfort in residents with dementia. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2018;20(2):120–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000424.

ROSTAD H, UTNE I, GROV E, SMASTUEN M, PUTS M, HALVORSRUD L. The impact of a pain assessment intervention on pain score and analgesic use in older nursing home residents with severe dementia: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;84:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.017.

RUSSELL T, MADSEN R, FLESNER M, RANTZ M. Pain management in nursing homes: what do quality measure scores tell us? J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(12):49–56. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20100504-07.

SAVVAS S, TOYE C, BEATTIE E, GIBSON S. An evidence-based program to improve analgesic practice and pain outcomes in residential aged care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014a;62(8):1583–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12935.

SAVVAS S, TOYE C, BEATTIE E, GIBSON S. Implementation of sustainable evidence-based practice for the assessment and management of pain in residential aged care facilities. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014b;15(4):819–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2013.09.002.

SHROPSHIRE M, STAPLETON S, DYCK M, KIM M, MALLORY C. Nonpharmacological interventions for persistent, noncancer pain in elders residing in long-term care facilities: an integrative review of the literature. Nurs Forum. 2018;53(4):538–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12284.

SMITH T, PURDY R, LATHAM S, KINGSBURY S, MULLEY G, CONAGHAN P. The prevalence, impact and management of musculoskeletal disorders in older people living in care homes: a systematic review. Reheumatol Int. 2016;36(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3322-1.

STACPOOLE M, HOCKELY J, THOMPSELL A, SIMARD J, VOLICER L. The Namaste care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(7):702–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4211.

SWAFFORD K, MILLER L, TSAI P, HERR K, ERSEK M. Improving the process of pain care in nursing homes: a literature synthesis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1080–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02274.x.

TAKAI Y, YAMAMOTO-MITANI N, CHIBA Y, KATO A. Feasibility and clinical utility of the Japanese version of the Abbey pain scale in Japanese aged care. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(2):439–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2012.02.003.

TAKAI Y, YAMAMOTO-MITANI N, FUKAHORI H, KOBAYASHI S, CHIBA Y. Nursing Ward Managers' perceptions of pain prevalence at the aged-care facilities in Japan: A Nationwide survey. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(3):e59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2011.04.004.

TAKAI Y, UCHIDA Y. Frequency and type of chronic pain care approaches used for elderly residents in Japan and the factors influencing these approaches. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2009;6(2):111–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-7924.2009.00129.x.

TAYLOR I, CONWAY V, KINGHT A. Measuring and addressing pain in people with limited communication skills: the "I hurt help me" pain; 2014.

TORVIK K, NORDTUG B, BRENNE I, ROGNSTAD M. Pain assessment strategies in home care and nursing homes in mid-Norway: a cross-sectional survey. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):602–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.01.001.

TORVIK K, KAASA S, KIRKEVOLD O, SALTVEDT I, HOLEN J, FAYERS P, et al. Validation of Doloplus-2 among nonverbal nursing home patients--an evaluation of Doloplus-2 in a clinical setting. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-9.

TOUSIGNANT-LAFLAMME Y, TOUSIGNANT M, LUSSIER D, LEBEL P, SAVOIE M, LALONDE L, et al. Educational needs of health care providers working in long-term care facilities with regard to pain management. Pain Res Manag. 2012;17(5):341–101. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/506352.

TRINKOFF A, LERNER N, STORR C, HAN K, JOHANTGEN M, GARTELL K. Leadership education, certification and resident outcomes in US nursing homes: cross -sectional secondary data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):334–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.002.

TSE M, LAU J, KWAN R, CHEUNG D, TANG A, NG, S., LEE, P. & YEUNG, S. Effects of play activities program for nursing home residents with dementia on pain and psychological well-being: cluster randomized controlled trial Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018:18.

TSE M, HO, S. Pain Management for Older Persons Living in nursing homes: A pilot study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(2):e10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2011.01.004.

TSE, MY., YEUNG, S.S., LEE, P.H., NG, SS. 2016. Effects of a Peer-Led Pain Management Program for Nursing Home Residents with Chronic Pain: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. Sep;17(9):1648–1657.

VAISMORADI M, SKAR L, SODERBERG S, BONDAS T. Normalizing suffering: A meta-synthesis of experiences of and perspectives on pain and pain management in nursing homes. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2016;11(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.31203.

VAN HERK R, VAN DIJK M, BIEMOLD N, TIBBOEL D, BAAR F, DE WIT R. Assessment of pain: can caregivers or relatives rate pain in nursing home residents? J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(17):2478–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02776.x.

VEAL F, WILLIAMS M, BEREZNICKI L, CUMMINGS M, WINZENBERG T. A retrospective review of pain management in Tasmanian residential aged care facilities BJGP Open. 2019:3.

VEAL F, WILLIAMS M, BEREZNICKI L, CUMMINGS M, THOMPSON A, PETERSON G, et al. Barriers to optimal pain Management in Aged Care Facilities: an Australian qualitative study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(2):177–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2017.10.002.

ZWAKHALEN S, DOCKING R, GNASS I, SIRSCH E, STEWART C, ALLCOCK N, et al. Pain in older adults with dementia: A survey across Europe on current practices, use of assessment tools, guidelines and policies. Schmerz. 2018;32(5):364–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-018-0290-x.

ZWAKHALEN S, VANT HOF C, HAMERS J. Systematic pain assessment using an observational scale in nursing home residents with dementia: exploring feasibility and applied interventions. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(21-22):3009–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04313.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the funders; the views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and not necessarily the funders.

Funding

CSO Catalytic Research Grant: CGA/19/15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: JH; review protocol: JH, JP, ASA, EH, FK; review process: JP, ASA; manuscript draft: JP, ASA; manuscript review: JH, EH, FK. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required for this research.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated to make a clear distinction in the reference list between the article and the supplementary files.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2.

[32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pringle, J., Mellado, A.S.A.V., Haraldsdottir, E. et al. Pain assessment and management in care homes: understanding the context through a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 21, 431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02333-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02333-4