Abstract

Objective

This study aims to assess the effects of antithrombotic therapy on the outcomes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in ICU patients, focusing on in-hospital mortality, rebleeding, and length of hospital and ICU stays.

Method

This retrospective observational study utilized the MIMIC-IV 2.2 database, which includes 513 ICU patients with LGIB.

Result

The in-hospital mortality rate was 7.6%, and the rebleeding rate was 11.1%. The average Oakland risk score among the study population was 22.54. Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified the use of antiplatelet drugs as an independent protective factor for in-hospital mortality (HR = 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.90, p = 0.029). Patients on anticoagulants experienced significantly longer hospital stays (13.1 ± 12.2 days vs. 17.4 ± 12.6 days, p = 0.031) compared to those not using these drugs. Propensity score matching also supported these findings, indicating that antithrombotic therapy was associated with lower in-hospital mortality and longer hospital stays even after adjusting for factors like age, gender, and primary diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our analysis using various statistical methods, including propensity score matching and multivariate regression, confirms that use of antithrombotic drugs in 2.3 days, particularly antiplatelets, are associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality. However, they may increase the risk of rebleeding and extend hospital stays in certain subgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is one of the most common reasons for hospital admission, with over 270,000 emergency-room visits and more than 100,000 admissions per year in the United States. The global incidence is 33–87 per 100,000 population [1]. Antithrombotic agents such as aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin are among the most commonly used drugs worldwide due to their ability to reduce thrombotic events. However, their use in patients with digestive hemorrhagic events is controversial because they may increase the risk of bleeding [2].

Existing literature indicates that continuing antithrombotic therapy after an upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) event is feasible and can provide cardiovascular benefits without significantly increasing adverse outcomes, although the recurrence rate of bleeding is elevated [3, 4]. However, data on the continuation of antithrombotic therapy following lower gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for severe bleeding, are limited [5]. Current guidelines on antithrombotic treatment for non-variceal UGIB are often applied interchangeably to LGIB due to a lack of specific evidence for LGIB [6, 7].

Given this gap in the literature, we conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the impact of antithrombotic therapy on the outcomes of LGIB in ICU patients. This study focuses on key clinical outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, rebleeding, and the length of hospital and ICU stays, thereby informing clinical decision-making and improving patient management strategies.

Methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective observational study of patients using the multi-center Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database (MIMIC-IV 2.2) [8, 9]. The MIMIC-IV database, maintained by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, includes over 70,000 ICU patients and features extensive documentation and public code contributed by a user community. Prior to data extraction, the author Ding Peng obtained all necessary access privileges. The database’s use was approved by the relevant review committees, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

We included patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), defined as hemorrhage of the colon and rectum caused by inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulum, angiodysplasia, etc. Patients with complications from pregnancy, trauma, poisoning, transplantation, HIV, or combined upper or middle gastrointestinal bleeding were excluded. Upper or middle gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as hemorrhage occurring in the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, defined as the all-cause mortality rate during the current hospitalization period. Secondary endpoints included rebleeding, hospital stay length, and ICU stay length. Rebleeding was defined as a hemoglobin decrease of more than 20 g/L from admission. The length of hospital/ICU stay is defined as the number of days between admission and discharge from the hospital/ICU. The study considered both antiplatelet agents (ticagrelor, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, etc.) and anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin, rivaroxaban, etc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.3.3 and SPSS 26.0 for Windows. R packages used included “tableone,” “survival,” “plyr,” “ggplot2,” and “foreign.” Descriptive analyses involved t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Kruskal tests for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Univariate survival analysis utilized Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. Logistic or Cox multivariate hazard regression analyses determined independent factors. Propensity score matching was employed to further assess the impact of antithrombotics on patient prognosis. All tests were two-sided, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Missing values were not interpolated.

Result

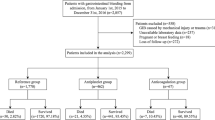

We identified 620 ICU patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), of whom 107 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 513 ICU patients were included in this study. Of these, 323 patients were primarily diagnosed with LGIB, while 190 had other diseases concurrent with LGIB. During their hospital stay, 39 (7.6%) patients died, and 57 (11.1%) experienced rebleeding. The average Oakland risk score was 22.54. Among these patients, 210 were treated with antithrombotic agents, including 190 on antiplatelet medications, 39 on anticoagulants, and one patient who received both during their hospital stay. The average duration of antithrombotic drug use was 2.3 days after ICU admission, with antiplatelets used for an average of 2.2 days and anticoagulants for 4.0 days.

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients on antithrombotic drugs were older, had a higher proportion of males, and more often had comorbidities such as myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), diabetes, and renal disease. Laboratory and physical examination results revealed higher creatinine, white blood cell counts, and BUN, but lower systolic blood pressure and SpO2 in the antithrombotic group. Risk scores and invasive treatment details are presented in Tables 2 and 3. These patients had higher CCI, APSIII, LODS, SAPSII, and MELD scores and a higher proportion required mechanical ventilation. Prognostically, the antithrombotic group had a higher rebleeding rate yet a lower in-hospital mortality rate (p = 0.010, log-rank = 6.1; K-M survival curve in Fig. 1).

We conducted propensity score matching (PSM) using five factors: APSIII, gender, age, primary diagnosis, and diverticula with a 1:1 matching ratio. The matching parameters used were distance of cbps and method of optimal. The results of the matching are presented in Tables 1 and 2, and 3. After PSM, patients in the antithrombotic drug group still had more comorbidities, including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), diabetes, and renal disease. In terms of prognosis, after PSM, patients taking antithrombotic drugs still had longer in-hospital stays but lower in-hospital mortality (p = 0.003, log-rank = 9, Kaplan-Meier survival curve in Fig. 2). The average duration of antithrombotic drug use was 3.2 days after ICU admission.

Considering the distinct mechanisms and indications of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs, their impact on patient outcomes may also differ. Therefore, we further conducted a risk factor analysis in the entire population using logistic and Cox regression methods. Table 4 presents the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for in-hospital mortality, revealing that cerebrovascular disease (OR 4.00, 95% CI 1.67–9.57, p = 0.002), liver disease (OR 2.25, 95% CI 0.99–5.07, p = 0.052), white blood cell count (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.09, p = 0.001), blood urea nitrogen (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.03, p = 0.004), systolic blood pressure (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.95-1.00, p = 0.048), and antiplatelet drugs (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.90, p = 0.029) were identified as independent predictors of in-hospital mortality. Table 5 shows the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for rebleeding, indicating that hemoglobin (HR 1.64, 95% CI 1.38–1.96, p < 0.001), platelets (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.99-1.00, p = 0.001), and heart rate (HR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00-1.03, p = 0.030) were significant predictors.

Subgroup analyses were conducted (Table 6). Among patients first diagnosed with other diseases concurrent with LGIB, those using antiplatelet agents had a lower in-hospital mortality rate (log-rank = 11.097, p = 0.001), and those using anticoagulant medications had longer hospital stays (13.1 ± 12.2 vs. 17.4 ± 12.6, p = 0.031). In patients first diagnosed with LGIB, those using antiplatelet drugs had a higher rate of rebleeding (5.5% vs. 17.5%, p = 0.001) and also had significantly prolonged hospital stays (6.0 ± 5.0 vs. 9.3 ± 8.9, p < 0.001), whereas those using anticoagulants only had prolonged hospital stays (6.9 ± 6.7 vs. 9.4 ± 5.8, p = 0.005).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the application of antithrombotic drugs in patients with LGIB through a large-scale population analysis. The study reports an in-hospital mortality rate of 7.6%, a rebleeding rate of 11.1% during hospitalization, and a 56.7% proportion of colon diverticular bleeding. These findings are similar to those of previous studies [10,11,12], indicating that despite focusing on ICU patients, the population is representative and the findings are generalizable.

The study found that antiplatelet drugs were associated with a significantly lower risk of in-hospital mortality among ICU patients with LGIB. This suggests that, despite the bleeding risks, the benefits of antithrombotic therapy, particularly antiplatelets, might outweigh the potential harms in certain patient populations. The lower in-hospital mortality rate can be attributed to the prevention of thrombotic events, which are common in critically ill patients. Clinically, this supports the continuation of antiplatelet therapy in ICU settings even when LGIB is present, as the overall benefit to survival is significant. Various statistical methods and subgroup analyses yielded encouraging results, suggesting that the use of antithrombotic drugs for 2.3 days is not only feasible but also reduces in-hospital mortality, particularly with antiplatelet drugs.

One of the notable findings was the increased risk of rebleeding associated with antiplatelet use. This highlights the need for careful patient monitoring and management. Clinicians must balance the risks of thrombotic events against the risk of rebleeding. The higher rate of rebleeding emphasizes the necessity for vigilant monitoring of hemoglobin levels and clinical signs of recurrent bleeding. It may be beneficial to develop protocols that allow for the safe administration of antithrombotics while minimizing the risk of rebleeding, possibly through dose adjustments or the use of adjunctive therapies that mitigate bleeding risks.

The study also revealed that patients on anticoagulants experienced significantly longer hospital stays. This finding has important implications for healthcare resource utilization and patient management. The prolonged hospital stays might be due to the need for more intensive monitoring and the management of bleeding complications. This highlights the importance of tailored patient care strategies that address both the prevention of thrombotic events and the management of bleeding risks. Clinicians might need to weigh the benefits of prolonged anticoagulant use against the potential for extended hospitalizations and the associated healthcare costs.

In this study, risk factors for in-hospital mortality included CVD and liver diseases as comorbidities, systolic blood pressure as a vital sign, and BUN, which has been reported in previous studies as related to prognosis in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly in ICU settings [13,14,15]. Elevated WBC, rarely reported in relation to LGIB prognosis, might suggest the presence of an infection in ICU patients, impacting their prognosis. This underscores the clinical need for vigilance regarding infections in patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Independent risk factors for rebleeding identified in this study include hemoglobin, platelets, and heart rate, which have been previously reported as related to adverse or rebleeding events in past studies.

Although this study provides significant insights into the use of antithrombotic drugs, it has limitations. Being retrospective with a degree of missing data might limit the generalizability of our findings. It is also impossible to completely avoid the impact of potential confounding factors on patient prognosis (such as the improvement of endoscopic treatment and vascular intervention treatment). Additionally, as the study population consisted of ICU patients, this leads to a certain selection bias. Future research should consider conducting multicenter, larger-scale clinical trials to verify and expand our results.

Conclusion

Our analysis using various statistical methods, including propensity score matching and multivariate regression, confirms that use of antithrombotic drugs in 2.3 days, particularly antiplatelets, are associated with a lower risk of in-hospital mortality. However, they may increase the risk of rebleeding and extend hospital stays in certain subgroups. This study underscores the importance of a nuanced approach to antithrombotic therapy in ICU patients with LGIB, advocating for personalized treatment plans, enhanced monitoring, and interdisciplinary collaboration to optimize patient outcomes.

Data availability

All data is publicly accessible.

References

Alali AA, Almadi MA, Barkun AN. Review article: advances in the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59(5):632–44.

Hallas J, Dall M, Andries A, Andersen BS, Aalykke C, Hansen JM, Andersen M, Lassen AT. Use of single and combined antithrombotic therapy and risk of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006;333(7571):726.

Peng D, Zhang M. The effect of aspirin in patients with nonvaricose upper gastrointestinal bleeding and risk factors analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;57(2):149–53.

Peng D, Zhai H. Application of antithrombotic drugs in different age-group patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2024;2024:1710708.

Little DHW, Robertson T, Douketis J, Dionne JC, Holbrook A, Xenodemetropoulos T, Siegal DM. Management of antithrombotic therapy after gastrointestinal bleeding: a mixed methods study of health-care providers. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(1):153–60.

Sengupta N, Feuerstein JD, Jairath V, Shergill AK, Strate LL, Wong RJ, Wan D. Management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated ACG guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118(2):208–31.

Triantafyllou K, Gkolfakis P, Gralnek IM, Oakland K, Manes G, Radaelli F, Awadie H, Camus Duboc M, Christodoulou D, Fedorov E et al. Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2021;53(8):850–868.

Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, Gayles A, Shammout A, Horng S, Pollard TJ, Hao S, Moody B, Gow B, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):1.

Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Glass L, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PC, Mark RG, Mietus JE, Moody GB, Peng CK, Stanley HE. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2000;101(23):E215–220.

Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Polo-Tomas M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, Perez-Gisbert J, Bujanda L, Castro M, Munoz M, et al. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1633–41.

Oakland K, Guy R, Uberoi R, Hogg R, Mortensen N, Murphy MF, Jairath V, Collaborative UKLGB. Acute lower GI bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, interventions and outcomes in the first nationwide audit. Gut. 2018;67(4):654–62.

Gralnek IM, Neeman Z, Strate LL. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1054–63.

Venkatesh PG, Njei B, Sanaka MR, Navaneethan U. Risk of comorbidities and outcomes in patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding - a nationwide study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(8):953–60.

Radaelli F, Frazzoni L, Repici A, Rondonotti E, Mussetto A, Feletti V, Spada C, Manes G, Segato S, Grassi E, et al. Clinical management and patient outcomes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53(9):1141–7.

Sun B, Man YL, Zhou QY, Wang JD, Chen YM, Fu Y, Chen ZH. Development of a nomogram to predict 30-day mortality of sepsis patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: an analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Heliyon. 2024;10(4):e26185.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Ding is responsible for writing the data analysis set paper, while Zhai Huihong is responsible for reviewing it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human ethics and consent to participate declarations

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC).

Consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board at the BIDMC granted a waiver of informed consent and approved the sharing of the research resource.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, D., Zhai, H. Application of antithrombotic drugs and risk factor analysis in ICU patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding from MIMIC-IV. BMC Gastroenterol 24, 319 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03380-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-024-03380-y