Abstract

Background

Gallstone disease (GSD) and its complications are major public health issues globally. Although many community-based studies had addressed the risk factors for GSD, little is known about the associations between dietary factors and risk of disease. The present study aimed to investigate the potential associations between dietary fibers with the risk of gallstone disease.

Methods

In this case–control study, 189 GSD patients with less than one month of diagnosis and 342 age‑matched controls were enrolled. Dietary intakes were assessed using a 168-item semi-quantitative validated food frequency questionnaire. Crude and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated through cox proportional hazards regression models.

Results

Comparing the highest versus the lowest tertile, significant reverse associations were observed between odds of GSD and each category of dietary fiber intake including total (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.37–0.7, P for trend = 0.015), soluble (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8, P for trend = 0.048) and insoluble (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9, P for trend < 0.001). The relationship between dietary fiber intake and the risk of gallstones was more prominent in overweight and obese subjects than in subjects with a normal body mass index.

Conclusion

Comprehensive assessment of the associations of dietary fiber intake with GSD showed that higher intakes of dietary fiber were significantly associated with reduced GSD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gallstone disease (GSD) is a major public health concern with a worldwide prevalence of 2–20% [1, 2]. Age and gender are two crucial factors in the prevalence of GSD. Compared to younger age, the prevalence of GSD increases more than 10 times in men and women over 60 and 50 years, respectively [3]. In addition to genetic predisposition, there are several pathogenic factors related to GSD, including increased biliary mucin secretion, hepatic hypersecretion of cholesterol and supersaturated bile, faster cholesterol crystallization and gallbladder stasis [4, 5]. Furthermore, there is an association between GSD and parameters related to metabolic syndrome such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia [6, 7].

Recently, rising attention has been addressed to detect the association of dietary factors and GSD. It has been reported that high prevalence of gallbladder diseases can be explained by increased intake of sugar and fat and decreased intake of whole grains and high-fiber foods [8]. Moreover, a cohort study of 5000 women participating in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicated that the increased risk of GSD-related hospitalization following dieting could be due to reduced dietary fiber intake [9]. Westernized diets (low-fiber, high-refined carbohydrate, high-fat) have also been shown to be associated with an increased risk of gallstones [4]. Fiber may have protective effects against gallstones by reducing the intestinal transit time and reducing the production of bile acids [10].

Since detecting the protective dietary factors is important in the management of GSD, thus, the purpose of the present study is to explore the association of dietary fiber and gallstone risk.

Methods and materials

This case–control study was conducted in the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases of Taleghani hospital affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Subjects with the age of 18 years and older, eagerness to participate, had approved GSD and a month or less passed from GSD diagnosis were considered to be included in the present study. Pregnant and lactating mothers and subjects with a history of intestinal disorders, autoimmune diseases, cancers, inflammatory and infectious diseases were excluded. Controls were matched to cases regarding the age (± 5 years) and sex. Patients admitted to other departments of the same hospital with no history of GSD and other liver ailments confirmed by ultrasonography, were randomly allocated to control group. It is worth mentioning that hospital controls are preferred over community controls when the cases obtained from the hospitals [11]. Because, the intended exposures such as health problems and debilitated behaviors of this type of controls are more likely to be similar to hospital cases. In fact, the prevalence of diseases in hospital controls is higher than that of the population-based controls [12]. Considering the exclusion of 5 cases with outrange mean energy intake (± 3SD) and subjects with uncompleted data, 189 cases and 342 controls (n = 531) remained for analyses. The protocol of the present study was approved by Research Institute of Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases Ethics Committee (IR.SBMU.RIGLD.REC.1396.159). All participants signed a written informed consent.

Dietary intake assessment

A valid reproducible semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [13] was used in order to determine the food intake of cases and controls before GSD diagnosis and hospital admission respectively, during a previous year. The frequency of food intake for each subject described on daily, weekly, monthly or yearly basis. The collected data were analyzed using Nutritionist IV software. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) food composition table (FCT) was used to calculate energy and nutrient contents. In addition to total fiber, the contents of insoluble and soluble fiber were calculated and expressed as gram per day.

Data collection

Information on socio-demographic factors, anthropometric measurements and other variables like physical activity, comorbidities, smoking habit and alcohol consumption in previous year collected by a trained interviewer through face-to-face interview. Participants body weight were measured to the nearest 100 g [14] while standing on digital scales (Soehnle, Berline, Germany). Measurement of height was done by a portable non-stretch meter to the nearest 0.5 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by division of weight in kilograms to square of height in meter. Data for physical activity was acquired by a valid questionnaire and described as metabolic equivalents hour per day (METs h/d). MET levels included in this questionnaire ranged from light (0.9 METs) to high-intensity activities (> 6 METs) [15, 16].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS software version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and histogram chart to check the normality of variables. In the present study, we described participant’s baseline characteristics and dietary intakes as mean ± SD for quantitative variables and numbers (percentage) for qualitative variables. Independent sample t-test and chi-square were applied for determining the differences between cases and controls for variables with normal distribution and categorical variables, respectively. Subjects were classified into tertiles regarding each category of fiber intake including total, insoluble and soluble fiber. P–value for the trend of GSD risk across each category of fiber intake was assessed using linear regression test. Occurrence of GSD and some of its risk factors including BMI, age and sex were illustrated across tertiles of each category of dietary fiber intake. The association between dietary fiber intakes with the odds of GSD was calculated using logistic regression. The analysis was adjusted for potential confounders including age and sex, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) of GSD across tertiles of each category of dietary fiber intake were reported in regard to some of the GSD risk factors including BMI, age and sex. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of subjects and their dietary intakes are shown in Table 1. Patients diagnosed with GSD had higher mean age, consumed more fat and more likely to be female (P < 0.05) but they had less physical activity, total and insoluble dietary fiber intake (P < 0.05) than the control group (Table 1).

The subjects’ characteristics and dietary intakes across the tertiles of dietary fiber intake are presented in Table 2. According to Table 2, there were no significant differences in age, alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity, weight and BMI between total dietary fiber intake tertiles whereas, significant differences in energy, carbohydrate and fat intakes were found to increase throughout the tertiles.

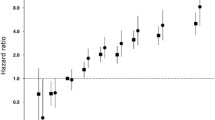

Multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for gallstone across tertiles of each category of fiber intake were illustrated in Table 3. In the crude model, only insoluble fiber intake showed a significant association with the risk of GSD (OR T3 vs T1 = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.3–0.9, P for trend < 0.001). In the age and sex-adjusted model, subjects in the highest tertile of total (OR = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.3–0.7, P for trend = 0.007) and insoluble (OR = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.34–0.84, P for trend < 0.001) dietary fiber intake had lower odds of GSD compared to the first tertile as a reference group. Additionally, in the multivariable-adjusted model, after further adjusting for energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption, significant reverse associations were observed between odds of GSD and each category of dietary fiber intake including total (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.37–0.7, P for trend = 0.015), soluble (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8, P for trend = 0.048) and insoluble (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9, P for trend < 0.001).

Multivariate odds ratios of total, soluble and insoluble fiber intake tertiles for risk of gallstone according to risk factor status at baseline are presented in Figs. 1, 2 and 3, respectively. According to Fig. 1, after adjusting for potential confounders, a significant relationship between total fiber intake and the risk of gallstones was found only in patients who were overweight (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.1–0.6, P for trend = 0.002) or obese (OR T3 vs. T1 = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.2–1.7, P for trend = 0.002), while, this relationship was not observed in people with normal BMI. Also, this relationship was significant in men and in people over 50 years old.

Multivariate odds ratios of total fiber intake tertiles for risk of gallstone according to risk factor status at baseline (multivariate logistic regression models for estimating ORs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as OR (95% CI). A, BMI < 25 vs 25–30 and ≥ 30 (P = 0.119 for interaction); B, age < 50 years vs ≥ 50 years (P = 0.711 for interaction); C, sex male vs female (P = 0.017 for interaction). Ref indicates reference group

Multivariate odds ratios of soluble fiber intake tertiles for risk of gallstone according to risk factor status at baseline (multivariate logistic regression models for estimating ORs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as OR (95% CI). A, BMI < 25 vs 25–30 and ≥ 30 (P = 0.119 for interaction); B, age < 50 years vs ≥ 50 years (P = 0.711 for interaction); C, sex male vs female (P = 0.017 for interaction)

Multivariate odds ratios of insoluble fiber intake tertiles for risk of gallstone according to risk factor status at baseline (multivariate logistic regression models for estimating ORs and 95% CIs, multivariable models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, smoking, alcohol, except for the respective stratifying factor). Data are reported as OR (95% CI). A, BMI < 25 vs 25–30 and ≥ 30 (P = 0.138 for interaction); B, age < 50 years vs ≥ 50 years (P = 0.581 for interaction); C, sex male vs female (P = 0.356 for interaction)

As shown in Fig. 2, a significant reverse association was observed between the highest and lowest tertiles of soluble dietary fiber intake and odds of GSD in subjects over 50 years old (OR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.2–0.7, P for trend = 0.039) and male gender (OR = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.2–0.8, P for trend < 0.001).

Figure 3 indicates that subjects in the highest tertile of insoluble dietary fiber intake with age above 50 (OR = 0.3; 95% CI: 0.2–0.6, P for trend < 0.001) and female gender (OR = 0.11; 95% CI: 0.04–0.3, P for trend < 0.001) had lower odds of GSD compared to the reference group. Also, this association was significant for all BMI categories.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the association of dietary total, soluble and insoluble fiber intake with the risk of gallstone has not been investigated yet. Comparing the highest versus the lowest tertile in the present case–control study showed that dietary total, soluble and insoluble fiber intake were associated with 56%, 49% and 44% lower GSD risk, respectively, after fully adjustment for potential confounders.

These finding are in line with several previous studies. Schwesinger et al. [17] have shown the protective effect of dietary soluble fiber against cholesterol gallstone formation. Two other observational studies have illustrated the inverse relationship between dietary fiber intake and the prevalence of gallstones [18, 19]. Another study investigating the effect of diet as a risk factor for cholesterol gallstone disease implicated that lower and higher intake of dietary fiber and refined sugar, were associated with propensity of gallstone formation, respectively [20]. In addition, consistent with our findings, a large number of epidemiological studies have reported an inverse association between insoluble dietary fiber and GSD [21,22,23,24].

In general, by decreasing the intestinal transit time, dietary fibers may reduce the persistence of bacteria located in the colon, which leads to a decrease in the production of secondary bile acids such as deoxycholate, and subsequently, less bile acids are absorbed [10, 25]. Lithogenicity of bile seems to be increased by deoxycholate, whereas chenodexycholate has contrary effect and thus it is used as a therapy to destruct gallstones [26]. Increasing the absorption of deoxycholate can stimulate biliary cholesterol saturation [27, 28]. This claim has been proved in an animal study conducted by Schwesinger et al., [17] who showed that fiber supplementation can prevent the formation of gallstones in prairie dogs on a lithogenic diet.

According to our findings, dietary fiber has the protective effect against GSD especially in older subjects and overweight and obese subjects. These findings are consistent with other published studies considering age and obesity as risk factors for GSD. Based on Masserat et al.’s [3] aging is an important factor leading to gallstone formation among Iranian. Moreover, higher BMI considered as an important risk factor for GSD [29, 30]. Additionally, we showed that women in the highest tertile of insoluble dietary fiber intake had the lowest risk of GSD. According to several studies, female gender is a possible risk factor for GSD [31, 32]. Thus, it seems that the protective effects of dietary fiber intake are more significant in people with related risk factors.

However, it is highly important to note that diets with low fiber content are usually accompanied by higher carbohydrate or/and fat intake, so the effect of fiber on GSD cannot be investigated independently [20]. There are some strengths attributed to current research. Contrary to previous studies, the current study has evaluated all types of biliary stone such as gallstone, common bile duct stone and the history of cholecystectomy during the last six months. Moreover, enrollment of newly diagnosed subjects declined the recall bias. The same interviewer proceeded the study so that the interviewer bias did not happen. Although, we had some limitations as well. First, due to the case–control design of the present study, it was not possible to show a causal relationship between dietary fiber intake and GSD. Second, due to the retrospective nature of the FFQ, the probability of recall bias should be considered. In order to be able to generalize the results, further research needs to be conducted, on a larger scale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, according to the findings of the current study, dietary fiber intakes have an inverse relationship with the risk of GSD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analyze of variance

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FCT:

-

Food composition table

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- IPAQ:

-

International physical activity questionnaire

- GSD:

-

Gallstone disease

- METs h/d:

-

Metabolic equivalents hour per day

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package Software for Social Science

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

References

Chang YR, Jang J-Y, Kwon W, Park JW, Kang MJ, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yun Y-B, Kim S-W. Changes in demographic features of gallstone disease: 30 years of surgically treated patients. Gut and Liver. 2013;7(6):719.

Huang J, Chang C-H, Wang J-L, Kuo H-K, Lin J-W, Shau W-Y, Lee P-H. Nationwide epidemiological study of severe gallstone disease in Taiwan. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9(1):1–10.

Massarrat S. Prevalence of gallstone disease in Iran. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16(5):564–7.

Di Ciaula A. Wang DQ-H, Portincasa P: an update on the pathogenesis of cholesterol gallstone disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34(2):71.

Thamer SJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of gallstone disease: a brief review. Biomed Chem Sci. 2022;1(2):70–7.

Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368(9531):230–9.

Wang DQ, Cohen DE, Carey MC: Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. J Lipid Res 2009, 50 Suppl(Suppl):S406–411.

Tamimi TM, Wosornu L. al-Khozaim A, Abdul-Ghani A: increased cholecystectomy rates in Saudi Arabia. Lancet. 1990;336(8725):1235–7.

Sichieri R, Everhart JE, Roth H. A prospective study of hospitalization with gallstone disease among women: role of dietary factors, fasting period, and dieting. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(7):880–4.

Marcus S, Heaton K. Effects of a new, concentrated wheat fibre preparation on intestinal transit, deoxycholic acid metabolism and the composition of bile. Gut. 1986;27(8):893–900.

Ruano-Ravina A, Pérez-Ríos M, Barros-Dios JM. Population-based versus hospital-based controls: are they comparable? Gac Sanit. 2008;22(6):609–13.

Moritz DJ, Kelsey JL, Grisso JA. Hospital controls versus community controls: differences in inferences regarding risk factors for hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(7):653–60.

Asghari G, Rezazadeh A, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Mehrabi Y, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reliability, comparative validity and stability of dietary patterns derived from an FFQ in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(6):1109–17.

Lee RD ND: Nutritional Assessment. 3rd ed.Columbus, OH: McGraw Hill;. 2003:165–168.

Aadahl M, Jørgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(7):1196–202.

Heidari Z, Jalali S, Sedaghat F, Ehteshami M, Rashidkhani B. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk among Iranian women: a case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;230:73–8.

Schwesinger WH, Kurtin WE, Page CP, Stewart RM, Johnson R. Soluble dietary fiber protects against cholesterol gallstone formation. Am J Surg. 1999;177(4):307–10.

Kameda H, Ishihara F, Shibata K, Tsukie E. Clinical and nutritional study on gallstone disease in Japan. Jpn J Med. 1984;23(2):109–13.

Scaggion GDS, Robbi R, Susanna S. Influence of dietary fibres in the genesis of cholesterol gallstone disease. Ital J Medicine. 1988;4:158–61.

Cuevas A, Miquel JF, Reyes MS, Zanlungo S, Nervi F. Diet as a risk factor for cholesterol gallstone disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(3):187–96.

Jorgensen TJL. Gallstones and diet in a Danish population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:821–6.

Ortega RM, Fernández-Azuela M, Encinas-Sotillo A, Andres P, López-Sobaler AM. Differences in diet and food habits between patients with gallstones and controls. J Am Coll Nutr. 1997;16:88–95.

Misciaga GCS, Leoci C, Guerra V, Cisternino AM, Ceo RTM. Diet, physical activity, and gallstones - a population-based, case-control study in southern Italy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:120–6.

Moerman CJSF, Kromhout D. Dietary risk factors for clinically diagnosed gallstones in middle-aged men. a 25-year follow-up study (the Zutphen Study). Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:248–54.

Marcus SN, Heaton KW. Intestinal transit, deoxycholic acid and the cholesterol saturation of bile–three inter-related factors. Gut. 1986;27(5):550–8.

Gaby AR. Nutritional approaches to prevention and treatment of gallstones. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(3):258–67.

Hayes KC, Livingston A, Trautwein EA. Dietary impact on biliary lipids and gallstones. Annu Rev Nutr. 1992;12:299–326.

TS: L-B: Nutrition and cholesterol gallstones. Proc Nutr Soc 1985, 44:127–134.

Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Elevated body mass index as a causal risk factor for symptomatic gallstone disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):2133–41.

Banim PJ, Luben RN, Bulluck H, Sharp SJ, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, Hart AR. The aetiology of symptomatic gallstones quantification of the effects of obesity, alcohol and serum lipids on risk. Epidemiological and biomarker data from a UK prospective cohort study (EPIC-Norfolk). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23(8):733–40.

Novacek G. Gender and gallstone disease. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2006;156(19–20):527–33.

Pazzi P, Putinati S, Limone G, Barbieri D, Trevisani L, Lupi L, Bighi S. [The effect of age and sex on gallbladder motor dynamics. an echographic study]. Radiol Med. 1989;77(4):365–8.

Acknowledgements

Authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Funding

No funding has been received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, ZY; Formal analysis, ZY; Methodology, Amir S, GD, SS and MG; Project administration, ANT and AH; Writing – original draft, ANT, Amin S and GD; Writing – review & editing, ZY and AH. All authors read and approved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The protocol of the present study was approved by Research Institute of Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases Ethics Committee (IR.SBMU.RIGLD.REC.1396.159). All participants signed a written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tehrani, A.N., Saadati, S., Yari, Z. et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of gallstone: a case–control study. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02752-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02752-0