Abstract

Background

Intestinal microinflammation with immune dysfunction due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reportedly precipitates post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. This study aimed to elucidate potential risk factors for subsequent development of irritable bowel syndrome, hypothesizing that it is associated with specific symptoms or patient backgrounds.

Methods

This single-center retrospective observational study (2020–2021) included adults with confirmed coronavirus disease requiring hospital admission and was conducted using real-world data retrieved from a hospital information system. Patient characteristics and detailed gastrointestinal symptoms were obtained and compared between patients with and without coronavirus disease-induced irritable bowel syndrome. Multivariate logistic models were used to validate the risk of developing irritable bowel syndrome. Moreover, daily gastrointestinal symptoms during hospitalization were examined in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Results

Among the 571 eligible patients, 12 (2.1%) were diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome following coronavirus disease. While nausea and diarrhea during hospitalization, elevated white blood cell count on admission, and intensive care unit admission were associated with the development of irritable bowel syndrome, nausea and diarrhea were identified as risk factors for its development following coronavirus disease, as revealed by the adjusted analyses (odds ratio, 4.00 [1.01–15.84] and 5.64 [1.21–26.31], respectively). Half of the patients with irritable bowel syndrome had both diarrhea and constipation until discharge, and constipation was frequently followed by diarrhea.

Conclusions

While irritable bowel syndrome was rarely diagnosed following coronavirus disease, nausea and diarrhea during hospitalization precede the early signs of irritable bowel syndrome following coronavirus disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mainly affects the lung tissues and causes various respiratory symptoms, which often develop into respiratory failure requiring intensive care [1, 2]. Although significantly high mortality rates of COVID-19 were recorded at the beginning of the pandemic owing to non-standardized care and resource limitations, several medications and vaccinations have prevented disease progression and improved clinical outcomes [3,4,5]. However, patients are still diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide without evident subsidence, and some patients who survive COVID-19 develop post-infectious symptoms [6, 7].

Although gastrointestinal (GI) diseases are not common in the early phase of COVID-19 [8, 9], GI symptoms often emerge and persist for several months even in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 [10, 11]. A previous study found that > 20% of patients reported diarrhea and nausea/vomiting during hospitalization and that 5%–10% of patients presented with lingering GI symptoms at 3 months after the initial infection [10]. Considering that the epithelium of the GI tract contains angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors [12], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) enters and affects the digestive tract. Moreover, as several studies have reported that both bacterial and viral infections in the GI tract can cause functional GI disorders (FGID), including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [13, 14], long-lasting GI symptoms even after virus clearance would be considered clinical signs of such diseases. A recent study identified that 2%–5% of patients with COVID-19 developed IBS at 6 months after infection [15, 16].

In addition to disruption of the epithelial barrier and intestinal microinflammation due to SARS-CoV-2, systemic immune dysregulation and psychological stress caused by COVID-19 might precipitate post-infectious FGID, particularly IBS [16]. While several studies have attempted to identify conditions before COVID-19 recovery that can predispose patients to post-infectious IBS [15,16,17], lack of detailed information on daily GI symptoms impedes the validation of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in post-infectious IBS following COVID-19.

Accordingly, we examined the characteristics and daily GI symptoms of patients with COVID-19 who required hospital admission using detailed electronic data obtained directly from a hospital information system. This study aimed to elucidate the potential risks and preceding early signs of the development of IBS, with the hypothesis that specific symptoms or patient backgrounds would be associated with the development of IBS following COVID-19.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a single-center retrospective observational study on patients with COVID-19 confirmed by a positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result for SARS-CoV-2. We used data from January 2020 to October 2021, which were obtained directly from the hospital information system of Keio University Hospital, a tertiary care center in Tokyo, Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all the registry participants. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Keio University School of Medicine (application number: 20200063).

Several patients with COVID-19 were identified in Japan in early 2020; thereafter, five surges of COVID-19 cases occurred in the study period. During these surges, the governor of Tokyo Metropolis announced several stay-at-home orders, each lasting for 1–2 months [18]. At the study institution, patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 who required oxygen, but not mechanical ventilation (MV), were treated by pulmonary internal medicine physicians in general wards, whereas intensive care physicians treated patients with severe COVID-19 who needed MV or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the intensive care unit (ICU).

GI symptoms during hospitalization were initially assessed by a treating physician, and gastroenterologists were always consulted when GI symptoms persisted. Although GI diseases can be diagnosed by either a treating physician or gastroenterologist, patients with confirmed or suspected GI diseases are always assessed by a gastroenterologist.

Data were obtained from the Donner Registry, which was established as a real-world data registry at Keio University School of Medicine. The Donner Registry has been prospectively collecting data of patients with COVID-19 from the hospital information system consisting of various records, such as demographics; auto-recorded parameters in patient-monitoring devices; descriptive records by healthcare providers, laboratories, and images; and detailed information on when these data were saved. Diseases diagnosed after admission were also available in the registry with codes using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. The registry was maintained by designated data managers who were blinded to the study analyses.

Study population

We included patients (1) aged ≥ 18 years, (2) diagnosed with COVID-19 with a positive RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2 from an upper respiratory tract sample obtained by nasopharyngeal swab, and (3) admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 treatment because of oxygen requirement or risks for exacerbation. Patients who had been diagnosed with IBS before COVID-19 diagnosis were excluded.

Data collection and definition

The collected data included patient demographics; comorbidities; date of a positive RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2; RT-PCR quantification cycle (Ct) for SARS-CoV-2; vital signs recorded by patient-monitoring devices and healthcare providers; laboratory data, such as white blood cell (WBC) count and hemoglobin, platelet, albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels; medications for COVID-19, including dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, tocilizumab, and remdesivir; a descriptive record of GI symptoms; GI diseases diagnosed after admission; and the date and time for each collected data. Length of hospitalization, length of ICU admission, and survival status were also assessed.

Daily GI symptoms during hospital stay were recorded by registered nurses at least three times a day and included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distention, abdominal discomfort, and abdominal pain. The stool form was observed by a healthcare provider and classified using the Bristol Stool Scale. Diarrhea was defined as 6 or 7 on the Bristol scale [19], and constipation was defined as 1 or 2 on the Bristol scale or absence of defecation for 3 consecutive calendar days. IBS was clinically diagnosed by board certified physicians who completed gastroenterology training using the Rome IV criteria with at least 3 months of observation of symptoms [20, 21]. In addition, among patients with data available on the duration of all medications and the timing of diagnosis, IBS was objectively confirmed either by (1) the date of IBS diagnosis that was ≥ 4 months after COVID-19 admission (at least 1-month interval before the initial IBS symptoms) or by (2) ≥ 3 months of use of medication for IBS with at least a 1-month interval before the initial IBS symptoms (therefore, ≥ 4 months of observation). Subtypes of IBS were not recorded in the registry and the follow-up periods varied across patients from 1 month to 1 year, depending on the date of admission for COVID-19 and presence of symptoms.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was development of IBS after recovery from COVID-19. The secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality and ICU-free and hospital-free days (a composite of in-hospital death and ICU/hospital length of stay, defined as the number of days alive and out of the ICU or hospital, respectively) up to day 30, in which the days were counted from the day of a positive RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2.

Statistical analysis

Patient data were classified into IBS and non-IBS groups based on the diagnosis of IBS following COVID-19. To identify possible risks for development of IBS following COVID-19, univariate analyses were performed on patient background characteristics, including demographics, vital signs, and laboratory findings on hospital admission, treatment for COVID-19, and severity of COVID-19 (requirement of ICU admission). The secondary outcomes were also compared between patients with and without IBS to further capture the clinical features of patients who developed IBS, although they were not considered risk factors for IBS.

Details of GI symptoms, including the type of GI symptoms, days from COVID-19 diagnosis to symptoms, and laboratories at the onset of any initial GI symptoms, were compared between the groups using univariate analyses. Then, adjusted analyses were performed using multivariate logistic models with the backward stepwise method to validate the potential risk of development of IBS. Covariates for the adjusted analysis were selected from the patient background characteristics and GI symptom-related data, considering the results of the univariate analyses. The number of covariates was determined following standard methods of sample size estimation for multivariate logistic regression: one to two potential predictors for ten outcome events [22].

Considering that the number of included patients was expected to be low because of the single-center design, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using bootstrapping (resampling the model 1,000 times) [23], and multivariate logistic regression analysis was repeated with the same covariates for the adjusted analysis. Additionally, the association between each potential trigger for IBS and the severity of COVID-19 was examined by subgroup analyses. Each potential risk factor identified in the adjusted analyses was compared between patients with and without IBS in subgroups determined by the requirement for ICU admission (severe vs. mild-to-moderate COVID-19).

Descriptive statistics are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (percentage). Patient characteristics and GI symptom-related data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. In hypothesis testing, a two-sided α threshold of 0.05 was considered significant. To avoid over- or under-estimating potentially important differences by a limited sample size, results are described using standardized differences and 95% confidence intervals (CI), wherein a standardized difference > 0.3 was considered a non-negligible difference. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 27.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

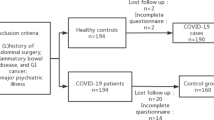

Among the 709 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 during the study period, 578 were admitted to the study institution and met all inclusion criteria. Seven patients were diagnosed with IBS before COVID-19 diagnosis; therefore, 571 patients were eligible for this study. Among them, 12 (2.1%) patients were diagnosed with IBS following recovery from COVID-19. In patients with objectively confirmed IBS, the median duration from admission for COVID-19 to IBS diagnosis was 5 months and the median duration of medication use for IBS was 4 months. A patient flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram. Among 709 patients with COVID-19 during the study period, 578 were admitted to the study institution and met all inclusion criteria. Seven patients were diagnosed with IBS before COVID-19 diagnosis and excluded; therefore, 571 patients were eligible for this study. Among them, 12 (2.1%) patients were diagnosed with IBS after COVID-19. *This included 3 patients aged < 18 years. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

The patients’ background characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients diagnosed with IBS had higher WBC counts upon hospital admission, and more patients with IBS had severe COVID-19 (required ICU admission) than those without IBS (6.1 [5.5–8.1] vs. 4.8 [3.9–6.2] 103/μL, p = 0.010 and 4 [33.3%] vs. 63 [11.3%], p = 0.041, respectively). Moreover, non-negligible differences (standardized difference > 0.3) were identified in the treatment for COVID-19, with less frequent use of dexamethasone and tocilizumab among patients with IBS than in those without IBS. The possible subtypes of IBS determined by medications are summarized in Table 2. In addition, the characteristics of patients with objectively confirmed IBS is shown in Table S1, which is similar to those of 12 patients with clinically diagnosed IBS.

Regarding secondary outcomes, patients with IBS had fewer ICU-free days compared to those without IBS, while in-hospital mortality and hospital-free days were comparable between patients with and without IBS (Table S2).

GI symptoms and risk for development of IBS

GI symptoms and related information are summarized in Table 3. Nausea and diarrhea were more frequently identified in patients with IBS than in those without (3 [25.0%] vs. 32 [5.7%], p = 0.032 and 10 [83.3%] vs. 245 [43.8%], p = 0.008, respectively). Meanwhile, other GI symptoms, including abdominal pain, number of days from COVID-19 diagnosis (positive PCR) to onset of symptoms, and laboratory parameters at the onset of initial GI symptoms were comparable between the groups; however, the number of days from COVID-19 diagnosis to onset of nausea was relatively longer in patients with IBS (10 [8-16] vs. 3 [1-10] days, standardized difference = 0.724). Moreover, the WBC count and CRP levels at the onset of initial GI symptoms were relatively higher in patients with IBS than in those without IBS.

Adjusted analysis was conducted using the multivariate logistic regression model to identify the risk factors for development of IBS following COVID-19; WBC count on admission, requirement of ICU admission (severe COVID-19), nausea, and diarrhea were entered. As the number of covariates in the logistic model needed to be limited because of the small sample size, they were selected using the backward stepwise method. Nausea and diarrhea were selected in the final model and determined as risk factors for the development of IBS (odds ratio [OR], 4.00; 95% CI, 1.01–15.84; p = 0.049 and OR, 5.64; 95% CI, 1.21–26.31; p = 0.028, respectively; Table 4). Sensitivity analysis with bootstrapping similarly revealed an association between diarrhea and development of IBS following COVID-19, but not for the relationship between nausea and consecutive IBS diagnoses (Table 4).

In the subgroup analyses (Table S3), nausea was associated with the development of IBS in patients with severe COVID-19 (3 [75.0%] vs. 10 [15.9%], p = 0.021) but not in those with mild-to-moderate COVID-19. Conversely, the association between diarrhea and the development of IBS following COVID-19 was not significant in patients with severe or non-severe COVID-19.

Daily GI symptoms in patients with IBS

Among the 12 patients diagnosed with IBS following COVID-19, 10 had no missing data on daily GI symptoms throughout the hospital stay. Diarrhea and constipation (including abdominal distention) were then summarized as typical symptoms of IBS (Fig. 2), whereas abdominal pain was not observed in any patient diagnosed with IBS following COVID-19.

Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients who developed irritable bowel syndrome following COVID-19. Diarrhea and constipation (including abdominal distention) are summarized in each patient who developed IBS following COVID-19 as typical symptoms of IBS. Half of the patients with IBS had both diarrhea and constipation until discharge, and constipation was frequently followed by diarrhea. Abdominal pain was not observed in this population. *Among the 12 patients who were diagnosed with IBS following COVID-19, the information of two patients who had missing data on daily gastrointestinal symptoms throughout the hospital stay is not presented in the figure. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome

Half of the patients with IBS had both diarrhea and constipation until discharge, and constipation was frequently followed by diarrhea. While many patients had diarrhea for at least 5 days, almost all of them had diarrhea or constipation for more than half of the length of their hospitalization.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, IBS was diagnosed in approximately 2% of patients with COVID-19, and analyses utilizing detailed daily GI symptoms revealed that diarrhea and nausea during COVID-19 treatment were significantly associated with the development of IBS. While several clinical features were identified as potential risk factors for development of IBS due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, the multivariate adjusted analysis revealed that diarrhea and nausea could precede early signs of post-infectious IBS following COVID-19.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the association between diarrhea/nausea and the development of IBS following COVID-19 should be considered. First, direct infection with SARS-CoV-2 in the GI tract would cause post-infectious IBS [24,25,26]. As medications for IBS were initiated at 1 month after COVID-19 diagnosis in this study, inflammation of enterocytes would take 1 month to develop post-infectious IBS. Second, given that ACE-2-mediated function is known to abnormally increase mucosal permeability and GI motility [27, 28], SARS-CoV-2 would have bound to the ACE-2 receptor in the GI tract among patients who developed IBS in this study. Notably, while previous studies have suggested that GI symptoms could persist after recovery from COVID-19 until the development of post-infectious IBS [29, 30], the present study indicated a latent period (1 month) until initiation of IBS medications. Third, the background characteristics of patients would affect the gut microbiota, which predisposes patients to the development of IBS [9, 16]. As ICU admission was more frequent in patients who had post-infectious IBS in this study, nausea and diarrhea could have been manifested as adverse effects of various medications, including vasopressors and sedatives, in such a population. Interestingly, Clostridioides difficile infection and antibiotic-related diarrhea were not identified in any patient with IBS in this study.

Although the severity of COVID-19 was not validated as an independent predictor of IBS after SARS-CoV-2 infection in this study, possible triggers for IBS would exist in patients with severe COVID-19. Cytokine imbalance frequently occurs in cases of severe COVID-19 [31], and gut functions are disturbed through destructive autoinflammation [21], which can eventually induce IBS. Moreover, psychological stress in severe COVID-19 can interfere with the brain-gut axis [32]. Here, higher WBC counts with a relatively higher rate of segmented neutrophils on hospital admission, relatively higher WBC counts and CRP levels at the onset of GI symptoms, and prolonged ICU stays were observed among patients with IBS following COVID-19. The relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and the development of IBS should be further examined in future studies with larger sample sizes.

Detailed GI symptoms during the treatment of COVID-19 were extensively examined in this study, and some distinctive daily changes in GI symptoms would be considered as early clinical signs of IBS following COVID-19. Although the GI symptoms during hospitalization for COVID-19 treatment are not necessarily equal to those for the diagnosis of IBS, predominant stool patterns until discharge were similar to those of IBS with diarrhea, known as IBS-D, or mixed IBS, known as IBS-M [33]. Conversely, abdominal pain during COVID-19 treatment was not necessary for the development of post-infectious IBS.

The present study obtained data regarding daily GI symptoms from real-world practice that were retrieved directly from a hospital information system. Therefore, a more robust association between GI symptoms during hospitalization for the treatment of COVID-19 and the development of IBS would be expected in this study compared with previous studies.

This study has some limitations. First, we utilized data from the Donner Registry to retrieve information directly from the hospital information system, which does not record the details of IBS diagnoses. Therefore, our results may differ if the GI symptoms for IBS diagnosis were over- or underestimated, although the Rome IV criteria were referred to in diagnosing IBS in this study. However, it should be noted that patients with objectively confirmed IBS, based on the details of medications and the timing of diagnosis, had similar characteristics to those with clinically diagnosed IBS. Second, the study was conducted at a single center with limited sample size and follow-up period. Therefore, other potential risks, such as the severity of COVID-19 and psychiatric status should be further examined in future studies. In addition, considering that new GI symptoms could emerge later than 3 months after recovery from COVID-19 [10], the prevalence of post-infectious IBS should be further examined in longer follow-up periods. Third, during the COVID-19 pandemic, several novel medications have been developed and reported to improve outcomes [3,4,5]. Therefore, some medications can mitigate the degree of viral load and may reduce the risk of the development of IBS. Furthermore, patients with a previous diagnosis of IBS were excluded in this study. As the accurate diagnosis of IBS is difficult for non-gastroenterologist, these patients may have been inappropriately excluded. Finally, as we investigated only patients who required hospitalization, our results cannot be generalized to patients with mild or no COVID-19 symptoms.

Conclusions

Diarrhea and nausea during hospitalization for COVID-19 treatment were associated with the development of IBS after SARS-CoV-2 infection, while IBS was rarely diagnosed (2%) in patients with COVID-19. The severity of COVID-19 and IBS subtypes following COVID-19 should be examined further in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

The data for this study are available from the Donner Registry of the Keio Donner Project; however, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under a license for the present study, so they are not publicly available. However, data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of Keio Donner Project at Keio University School of Medicine for researchers who meet the criteria for accessing confidential data.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- ACE-2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

- FGID:

-

Functional GI disorders

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region — case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–22.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9.

Abani O, Abbas A, Abbas F. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY Collaborative Group): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1637–45.

Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—Final Report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–26.

Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O, Rosa RG, Veiga VC, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1307–16.

Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, Gunasekera P, Morice AH, Crooks MG. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199:113–9.

Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–5.

Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757–66.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Blackett JW, Li J, Jodorkovsky D, Freedberg DE. Prevalence and risk factors for gastrointestinal symptoms after recovery from COVID-19. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34:e14251.

Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Mathur A, Singh RK, Nath A, Garg A, et al. The spectrum of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with coronavirus Disease-19: predictors, relationship with disease severity, and outcome. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00259.

Scialo F, Daniele A, Amato F, Pastore L, Matera MG, Cazzola M, et al. ACE2: the major cell entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung. 2020;198:867–77.

Barbara G, Grover M, Bercik P, Corsetti M, Ghoshal UC, Ohman L, et al. Rome foundation working team report on post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:46-58.e7.

Zanini B, Ricci C, Bandera F, Caselani F, Magni A, Laronga AM, et al. Incidence of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and functional intestinal disorders following a water-borne viral gastroenteritis outbreak. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:891–9.

Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Rahman MM, Mathur A, Rai S, Akhter M, et al. Post-infection functional gastrointestinal disorders following coronavirus disease-19: A case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:489–98.

Settanni CR, Ianiro G, Ponziani FR, Bibbò S, Segal JP, Cammarota G, et al. COVID-19 as a trigger of irritable bowel syndrome: a review of potential mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:7433–45.

Segal JP, Mak JWY, Mullish BH, Alexander JL, Ng SC, Marchesi JR. The gut microbiome: an under-recognised contributor to the COVID-19 pandemic? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820974914.

Yamamoto R, Kaito D, Homma K, Endo A, Tagami T, Suzuki M, et al. Early intubation and decreased in-hospital mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care. 2022;26:124.

Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4.

Fukudo S, Okumura T, Inamori M, Okuyama Y, Kanazawa M, Kamiya T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:193–217.

Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016–5085(16):00222–5.

Palazón-Bru A, Folgado-de la Rosa DM, Cortés-Castell E, López-Cascales MT, Gil-Guillén VF. Sample size calculation to externally validate scoring systems based on logistic regression models. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0176726.

Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJJM, Eijkemans MJC, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JDF. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:774–81.

Jiang X, Luo M, Zou Z, Wang X, Chen C, Qiu J. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected case with viral detection positive in stool but negative in nasopharyngeal samples lasts for 42 days. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1807–9.

Lamers MM, Beumer J, van der Vaart J, Knoops K, Puschhof J, Breugem TI, et al. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science. 2020;369:50–4.

Iacob T, Țățulescu DF, Lupșe MS, Dumitrașcu DL. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome after a laboratory-proven enteritis. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:3517–22.

Hashimoto T, Perlot T, Rehman A, Trichereau J, Ishiguro H, Paolino M, et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487:477–81.

Zhang H, Li HB, Lyu JR, Lei XM, Li W, Wu G, et al. Specific ACE2 expression in small intestinal enterocytes may cause gastrointestinal symptoms and injury after 2019-nCoV infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:19–24.

Austhof E, Bell ML, Riddle MS, Catalfamo C, McFadden C, Cooper K, et al. Persisting gastrointestinal symptoms and post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 infection: results from the Arizona CoVHORT. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150:e136.

Noviello D, Costantino A, Muscatello A, Bandera A, Consonni D, Vecchi M, et al. Functional gastrointestinal and somatoform symptoms five months after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A controlled cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34:e14187.

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–4.

Ju Y, Chen W, Liu J, Yang A, Shu K, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of centralized isolation vs home isolation on psychological distress in patients with COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 2021;143:110365.

Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:133–46.

Acknowledgements

None. Keio Donner Project; Takanori Kanai, MD, PhD3, Masayuki Amagai, MD, PhD6, Hideyuki Saya, MD, PhD7, Hiroshi Nishihara, MD, PhD8. 3Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. 6Department of Dermatology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. 7Division of Gene Regulation, Institute for Advanced Medical Research, Keio University School of Medicine. 8Genomics Unit, Keio Cancer Center, Keio University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

RY, TMasaoka, and KH conceived and designed the study, interpreted data, drafted the manuscript, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. AY, TMatsuoka, RT, and MW contributed to the data acquisition and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. JS interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have reviewed, discussed, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Keio University School of Medicine (application number: 20200063) for conducting research with humans in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file1:

Table S1. Characteristics of patients with objectively confirmed irritable bowel syndrome. Table S2. Secondary outcomes in patients with and without IBS. Table S3. Abdominal symptoms and IBS in subgroups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, R., Yamamoto, A., Masaoka, T. et al. Early symptoms preceding post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome following COVID-19: a retrospective observational study incorporating daily gastrointestinal symptoms. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02746-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02746-y