Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is widely known to induce a variety of extrapulmonary manifestations. Gastrointestinal symptoms have been identified as the most common extra-pulmonary manifestations of COVID-19, with an incidence reported to range from 3 to 61%. Although previous reports have addressed abdominal complications with COVID-19, these have not been adequately elucidated for the omicron variant. The aim of our study was to clarify the diagnosis of concomitant abdominal diseases in patients with mild COVID-19 who presented to hospital with abdominal symptoms during the sixth and seventh waves of the pandemic of the omicron variant in Japan.

Methods

This study was a retrospective, single-center, descriptive study. In total, 2291 consecutive patients with COVID-19 who visited the Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Kansai Medical University Medical Center, Osaka, Japan, between January 2022 and September 2022 were potentially eligible for the study. Patients delivered by ambulance or transferred from other hospitals were not included. We collected and described physical examination results, medical history, laboratory data, computed tomography findings and treatments. Data collected included diagnostic characteristics, abdominal symptoms, extra-abdominal symptoms and complicated diagnosis other than that of COVID-19 for abdominal symptoms.

Results

Abdominal symptoms were present in 183 patients with COVID-19. The number of patients with each abdominal symptom were as follows: nausea and vomiting (86/183, 47%), abdominal pain (63/183, 34%), diarrhea (61/183, 33%), gastrointestinal bleeding (20/183, 11%) and anorexia (6/183, 3.3%). Of these patients, 17 were diagnosed as having acute hemorrhagic colitis, five had drug-induced adverse events, two had retroperitoneal hemorrhage, two had appendicitis, two had choledocholithiasis, two had constipation, and two had anuresis, among others. The localization of acute hemorrhagic colitis was the left-sided colon in all cases.

Conclusions

Our study showed that acute hemorrhagic colitis was characteristic in mild cases of the omicron variant of COVID-19 with gastrointestinal bleeding. When examining patients with mild COVID-19 with gastrointestinal bleeding, the potential for acute hemorrhagic colitis should be kept in mind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, as the cause of a respiratory illness designated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The clinical course ranges from asymptomatic to critically ill, and approximately 5–20% of patients with COVID-19 develop severe pneumonitis, with some progressing to life-threatening respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiple organ failure and various other pathological conditions [1,2,3,4,5]. The typical clinical symptoms of patients with mild COVID-19 are fever, cough, dyspnea and myalgia or fatigue. Moreover, COVID-19 is widely known to also induce a variety of extrapulmonary manifestations, with gastrointestinal manifestations being the most common of them [6, 7].

The incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 was reported to range from 3 to 61%. The prevalence of anorexia, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain with COVID-19 was reported to be 21 to 34.8%, 7 to 26.4%, 9 to 33.7% and 1.9 to 14.5%, respectively [7,8,9,10].

In Japan, 1.7 million patients were infected with COVID-19 from the first to the fifth wave (from March 2020 to December 2021). Among the more highly infectious strains, omicron variants BA1, BA2 and BA5 caused widespread infection, and there were up to 20 million patients with COVID-19 during the sixth and seventh waves (from January 2022 to November 2022) in Japan. Although previous reports have addressed abdominal complications with COVID-19, these have not been adequately elucidated for the omicron variant, the latest strain.

As the infection spread in Japan, many patients with mild COVID-19 presented to emergency departments with extra-pulmonary symptoms. Thus, the aim of our study was to clarify the diagnosis of concomitant abdominal diseases in patients with mild COVID-19 who presented to the hospital with abdominal symptoms during the sixth and seventh waves of the pandemic in Japan.

Methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective, single-center, descriptive study. In total, 2291 consecutive patients who were diagnosed as having COVID-19 confirmed by polymerase chain reaction or antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal swab samples and who presented to the emergency department of Kansai Medical University Medical Center, Osaka, Japan, between January 1, 2022, and September 30, 2022, were potentially eligible for the study. To target patients with mild COVID-19 and avoid bias, patients delivered by ambulance or who transferred from other hospitals were not included. The inclusion criterion was patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal manifestations. The exclusion criteria were being pregnant and age under 18 years old. In principle, emergency physicians with 5 to 10 years of experience examined and diagnosed the patients, and blood tests and computed tomography (CT) scans could be performed at any time if necessary. To prevent the transmission of COVID-19, endoscopy cannot be easily performed, and therefore, the performance of endoscopy was not considered mandatory for diagnosis in this study. After application of the exclusion criteria, 183 patients were selected. Clinical outcomes were monitored up to September 30, 2022.

Data collection

We collected and described physical examination results, medical history, hematological and biochemical data, CT findings and treatments as obtained from the electronic medical records of the patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data collected included sex, age, race, body mass index, abdominal symptoms (nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding and anorexia), extra-abdominal symptoms (cough or sputum, fever, sore throat, headache, fatigue, dysosmia and dysgeusia), days from onset to presentation, origin, vaccination frequency, complicated diagnosis other than that of COVID-19 for abdominal symptoms, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, chronic renal disease, liver disease, gastrointestinal disease, psychiatric disorder, malignancy disease and autoimmune disease), antiviral treatment received (antiviral drugs and neutralizing antibody therapy) and outcome (outpatient treatment, hospitalization or therapeutic interventions).

Statistical analysis and ethical concerns

Categorical data are summarized as frequencies and proportion, whereas continuous variables as shown as the median and 25–75th percentile range. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 28.0 software (IBM Corp, USA). This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Kansai Medical University Medical Center—Institutional Review Board (Study Number: 2022193). Due to the retrospective study design, the requirement for written informed consent was waived (Kansai Medical University Medical Center—Institutional Review Board).

Results

Patients, manifestations and hospitalizations

In total, 2291 patients with COVID-19 presented to the emergency department of Kansai Medical University Medical Center, Osaka, Japan, between January and September 2022. After removing the patients meeting the exclusion criteria, 1625 patients were included in the analyses, of whom 183 had abdominal symptoms (Fig. 1). The majority of patients were female (111/183, 61%), and the median age was 42 (range 18–90) years old. The number of patients with each abdominal symptom was as follows: nausea and vomiting (86/183, 47%), abdominal pain (63/183, 34%), diarrhea (61/183, 33%), gastrointestinal bleeding (20/183, 11%) and anorexia (6/183, 3.3%). Extra-abdominal symptoms included the following: cough or sputum (90/183, 49%), fever (78/183, 43%), sore throat (65/183, 36%), headache (43/183, 23%), fatigue (33/183, 18%), dysgeusia (4/183, 2.2%) and dysosmia (1/183, 0.5%). Nearly one half of the patients (89/183, 49%) underwent chest and abdominal CT, whereas one third (58/183, 32%) underwent only chest CT. Most patients (146/183, 80%) presented directly, and the others (37/183, 20%) were referred from public health centers or clinics. Only some patients (28/183, 15%) were hospitalized for treatment (Table 1).

Diagnosis

Most patients (146/183, 80%) did not have a complicated diagnosis other than that of COVID-19 for abdominal symptoms. Among the remaining 37 patients, 17 were diagnosed as having acute hemorrhagic colitis, five had drug-induced adverse events, two had retroperitoneal hemorrhage, two had appendicitis, two had choledocholithiasis, two had constipation, two had anuresis and one patient each had cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, ruptured esophageal varices, spermatic cord torsion and hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, respectively. Pharmaceutical therapy suspected of causing drug-related complications included nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir in two patients each and casirivimab and imdevimab in one patient each (Fig. 2) (Table 2).

Characteristics of the 17 patients diagnosed as having acute hemorrhagic colitis

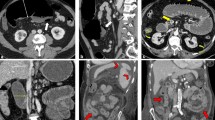

The majority of patients were female (11/17, 65%), and median age was 42 (range 23–84) years old. The number of patients with each abdominal symptom was as follows: gastrointestinal bleeding (17/17, 100%) and abdominal pain (15/17, 88%), diarrhea (2/17, 12%), nausea (1/17, 6%) and vomiting (1/17, 6%). The laboratory data were as follows: D-dimer (µg/mL), CRP (mg/dL) and anti-SARS-CoV-2 S antibody (U/mL) (0.5 [0.2–0.9], 0.8 [0.3–2.5] and 1109 [0–6685], median [1st IQR–3rd IQR], respectively). The CT findings of all patients showed the colon appearing as thickening along with peri-colic fat stranding (descending 7/17, descending to sigmoid 3/17, splenic flexure to sigmoid 3/17, sigmoid 2/17 and splenic flexure to descending colon 2/17).

Discussion

We described patients with mild COVID-19 and abdominal symptoms who presented to our emergency department during the sixth and seventh waves (from January 2022 to September 2022) in which the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA1, BA2 and BA5 were widespread. About one tenth of the patients (183/1625, 11%) experienced some abdominal symptoms. In 37 patients, diagnoses other than COVID-19 as the cause of abdominal symptoms included acute hemorrhagic colitis, drug-related adverse events, retroperitoneal bleeding, appendicitis, cholangitis, constipation and urinary retention in that order.

Among the 20 patients with COVID-19 who had gastrointestinal bleeding, 85% (17/20) were diagnosed as having acute hemorrhagic colitis, which was characteristic in this study (Fig. 3). The diagnostic criteria of acute hemorrhagic colitis were satisfied by two elements, the colon appearing as thickening along with peri-colic fat stranding on abdominal CT, and gastrointestinal bleeding as a symptom. All colitis was localized in the left hemi-colon, from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon. The lesion site was similar to that of ischemic colitis, so it was necessary to determine a differential diagnosis by imaging. A previous study reported that ischemic colitis was more common in non-COVID-19 women over the age of 49 years [11, 12]. However, 11/17 patients diagnosed as having acute hemorrhagic colitis were younger than 50 years in the present study. Ischemic colitis is commonly categorized into two classical patterns, occlusive and nonocclusive. However, there was little elevation of D-dimer (< 3.8 µg/mL) suggesting thrombosis in the patients with acute hemorrhagic colitis in this study. Although no endoscopic or pathological examination was performed, the epidemiology was thought to differ from that of ischemic colitis. COVID-19 is known to be a systemic disease, with a specific tropism for endothelial cells that leads to microvascular disease with multisystemic involvement, and therefore, it also affects the gastrointestinal system [13]. Bleeding and ischemic manifestations are also frequent, with spontaneous hematomas in soft tissues being the most common. Ischemic and hemorrhagic abdominal complications such as ischemic colitis, small bowel ischemia, retroperitoneal bleeding and others may occur in patients with COVID-19 [14,15,16,17,18,19]. The overall rate of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with COVID-19 reportedly ranged from 1.1 to 13%, with most patients with gastrointestinal bleeding being critically ill men with a mean age of 67.5 years [14]. COVID-19-induced colitis that presents with abdominal pain, watery diarrhea and gastrointestinal bleeding consistent with an acute hemorrhagic colitis was reported as an uncommon occurrence [20]. Two injury mechanisms of inflammatory responses induced by COVID-19 have been reported: one is mediated by angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE)-2 receptors, and the other is independent of ACE-2 receptors [21,22,23]. Furthermore, as ACE-2 receptors are widely expressed not only in the airway and alveolar epithelial cells but also in the intestinal epithelial cells, renal epithelial cells, myocardial cells and vascular endothelial cells, SARS-CoV-2 infection induces systemic local inflammation via systemic ACE-2 receptors [21,22,23,24]. The independent mechanism is the accumulation of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-7, TNF and inflammatory chemokines, which cause an overwhelming viremic response with resultant injury to the digestive mucosa that damages the digestive system through a viral inflammatory response [25,26,27,28,29].

Representative computed tomography (CT) images from patients with COVID-19 and acute hemorrhagic colitis. A–C Axial and coronal CT images of a 45-year-old patient showing evidence of acute hemorrhagic colitis involving the descending to sigmoid colon appearing as thickening along with peri-colic fat stranding (red arrow and thin red arrows). D, E Axial CT images of a 59-year-old patient revealed acute hemorrhagic colitis involving the descending colon that showed marked thickening with peri-colic fat stranding (yellow arrowheads). F, G Axial CT images of a 39-year-old patient revealed acute hemorrhagic colitis involving the splenic flexure to descending colon that showed marked thickening with peri-colic fat stranding (white arrowhead and thin white double-headed arrow)

There were two patients in the present study with retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to a ruptured visceral artery aneurysm (Fig. 4), which is a relatively rare condition. Its reported prevalence is approximately 1% in the total population, and it is found in 0.01–0.2% of autopsy cases, most of which are detected following rupture [30, 31]. Although the increased risk of bleeding could be related to endothelial dysfunction, coagulopathy or disseminated intravascular coagulation in COVID-19, the risk of bleeding in patients with mild COVID-19 was not reported to increase [32]. There have been some reports of retroperitoneal hemorrhage in severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19 requiring anticoagulant therapy [13, 33], but the COVID-19 in the two patients in our study was mild with no evidence of pneumonitis, and neither patient received antithrombotic therapy. Although the relation of retroperitoneal hemorrhage with mild COVID-19 remains unclear, our two patients required emergency intervention due to lethal complications.

Representative computed tomography (CT) images of retroperitoneal hemorrhage in patients with COVID-19. A–C Axial, coronal and 3D CT images from a 56-year-old patient show evidence of retroperitoneal hemorrhage (thin yellow double-headed arrow) with pseudoaneurysm of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (yellow arrows). D–F Axial, sagittal and 3D CT images from a 41-year-old patient show evidence of retroperitoneal hemorrhage (thin red double-headed arrow, D) with pseudoaneurysm of the anterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (red arrows)

This study has several limitations. First, as it was a retrospective, single-center, observational, descriptive study, there was possible bias in relation to the patient population. Second, we diagnosed acute hemorrhagic colitis based on symptoms and CT scans. No endoscopy or histological or pathogenic examination was performed. Therefore, other diseases, such as bacterial and viral diseases, could not be adequately ruled out.

Conclusion

Our study showed that acute hemorrhagic colitis was characteristic in patients with mild COVID-19 of the omicron variant who had gastrointestinal bleeding. About 10% of these patients with abdominal symptoms had acute hemorrhagic colitis, and thus, its occurrence might be relatively more frequent than previously reported. When examining patients with mild COVID-19 and gastrointestinal bleeding, acute hemorrhagic colitis should be kept in mind. About 1% of the patients with abdominal symptoms had retroperitoneal hemorrhage, so even patients with mild disease might suffer retroperitoneal hemorrhage induced by COVID-19.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting-enzyme

References

Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):401–2.

Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–3.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Yoshimura Y, Sasaki H, Horiuchi H, Miyata N, Tachikawa N. Clinical characteristics of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on a cruise ship. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26(11):1177–80.

da Rosa Mesquita R, Francelino Silva Junior LC, Santos Santana FM, Farias de Oliveira T, Campos Alcântara R, Monteiro Arnozo G, et al. Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in the general population: systematic review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133:377–82.

Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–32.

Ye L, Yang Z, Liu J, Liao L, Wang F. Digestive system manifestations and clinical significance of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic literature review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;36(6):1414–22.

Weng LM, Su X, Wang XQ. Pain symptoms in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a literature review. J Pain Res. 2021;14:147–59.

Elmunzer BJ, Spitzer RL, Foster LD, Merchant AA, Howard EF, Patel VA, et al. Digestive manifestations in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1355–65.

Suh DC, Kahler KH, Choi IS, Shin H, Kralstein J, Shetzline M. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome or constipation have an increased risk for ischaemic colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(6):681–92.

Longstreth GF, Yao JF. Epidemiology, clinical features, high-risk factors, and outcome of acute large bowel ischemia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1075–80.

Bonaffini PA, Franco PN, Bonanomi A, Giaccherini C, Valle C, Marra P, et al. Ischemic and hemorrhagic abdominal complications in COVID-19 patients: experience from the first Italian wave. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27:165.

Negro A, Villa G, Rolandi S, Lucchini A, Bambi S. Gastrointestinal bleeding in COVID-19 patients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2022;45(4):267–75.

Krejčová I, Berková A, Kvasnicová L, Vlček P, Veverková L, Penka I, et al. Ischemic colitis in a patient with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2022;16:526–34.

Uhlenhopp DJ, Ramachandran R, Then E, Parvataneni S, Grantham T, Gaduputi V. COVID-19-associated ischemic colitis: a rare manifestation of COVID-19 infection—case report and review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2022;10:1–6.

Norsa L, Bonaffini PA, Caldato M, Bonifacio C, Sonzogni A, Indriolo A, et al. Intestinal ischemic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2: results from the ABDOCOVID multicentre study. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(32):5448–59.

Funt SA, Cohen SL, Wang JJ, Sanelli PC, Barish MA. Abdominal pelvic CT findings compared between COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 negative patients in the emergency department setting. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(4):1498–505.

Barkmeier DT, Stein EB, Bojicic K, Otemuyiwa B, Vummidi D, Chughtai A, et al. Abdominal CT in COVID-19 patients: incidence, indications, and findings. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(3):1256–62.

Stawinski P, Dziadkowiec KN, Marcus A. COVID-19-induced colitis: a novel relationship during troubling times. Cureus. 2021;13(6):e15870.

Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–9.

Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1653–9.

Becker RC. COVID-19-associated vasculitis and vasculopathy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50:499–511.

Lukiw WJ, Pogue A, Hill JM. SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and neurological targets in the brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022;42:217–24.

Tang A, Tong ZD, Wang HL, Dai YX, Li KF, Liu JN, et al. Detection of novel coronavirus by RT-PCR in stool specimen from asymptomatic child, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1337–9.

Xie C, Jiang L, Huang G, Pu H, Gong B, Lin H, et al. Comparison of different samples for 2019 novel coronavirus detection by nucleic acid amplification tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:264–7.

Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831-3.e3.

Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:355–62.

Funt SA, Cohen SL, Wang JJ, Sanelli PC, Barish MA. Abdominal pelvic CT findings compared between COVID-19 positive and COVID-19 negative patients in the emergency department setting. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:1498–505.

Panayiotopoulos YP, Assadourian R, Taylor PR. Aneurysms of the visceral and renal arteries. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78:412–9.

Hossain A, Reis ED, Dave SP, Kerstein MD, Hollier LH. Visceral artery aneurysms: experience in a tertiary-care center. Am Surg. 2001;67:432–7.

Katsoularis I, Fonseca-Rodríguez O, Farrington P, Jerndal H, Lundevaller EH, Sund M, et al. Risks of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and bleeding after covid-19: nationwide self-controlled cases series and matched cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377:e069590.

Ano S, Shinkura Y, Kenzaka T, Kusunoki N, Kawasaki S, Nishisaki H. A ruptured left gastric artery aneurysm that neoplasticized during the course of coronavirus disease 2019: a case report. Pathogens. 2022;11(7):815.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rise Japan LCC for carefully proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM participated in study design, data collection and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. DW conceived the study and its design and helped to draft the manuscript. TO, FS, KY, YN and YK participated in study design and data collection. YK had a major impact on the interpretation of data and critical appraisal of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Kansai Medical University Medical Center—Institutional Review Board (Study Number: 2022193). Due to the retrospective study design, written informed consent was waived (Kansai Medical University Medical Center—Institutional Review Board).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruyama, S., Wada, D., Oishi, T. et al. A descriptive study of abdominal complications in patients with mild COVID-19 presenting to the emergency department: a single-center experience in Japan during the omicron variant phase. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 43 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02681-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02681-y