Abstract

Background

Given the limited effectiveness of the current Chinese colorectal cancer (CRC) screening procedure, adherence to colonoscopy remains low. We aim to develop and validate a scoring system based on individuals who were identified as having a high risk in initial CRC screening to achieve more efficient risk stratification and improve adherence to colonoscopy.

Methods

A total of 29,504 screening participants with positive High-Risk Factor Questionnaire (HRFQ) or faecal immunochemical test (FIT) who underwent colonoscopy in Tianjin from 2012–2020 were enrolled in this study. Binary regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between risk factors and advanced colorectal neoplasia. Internal validation was also used to assess the performance of the scoring system.

Results

Male sex, older age (age ≥ 50 years), high body mass index (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2), current or past smoking and weekly alcohol intake were identified as risk factors for advanced colorectal neoplasm. The odds ratios (ORs) for significant variables were applied to construct the risk score ranging from 0–11: LR, low risk (score 0–3); MR, moderate risk (score 4–6); and HR, high risk (score 7–11). Compared with subjects with LR, those with MR and HR had ORs of 2.47 (95% confidence interval, 2.09–2.93) and 4.59 (95% confidence interval, 3.86–5.44), respectively. The scoring model showed an outstanding discriminatory capacity with a c-statistic of 0.64 (95% confidence interval, 0.63–0.65).

Conclusions

Our results showed that the established scoring system could identify very high-risk populations with colorectal neoplasia. Combining this risk score with current Chinese screening methods may improve the effectiveness of CRC screening and adherence to colonoscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and second most lethal cancer worldwide [1]. In terms of cancer incidence and mortality in China, in 2020, there were 0.56 million new cases of CRC, and CRC was responsible for 0.29 million deaths [2]. Generally, the development of CRC is a multistage and slow process occurring over several decades, with colorectal neoplasia (CRN) and advanced colorectal neoplasm (ACN) representing key steps in progression to CRC [3]. If detected and treated in the early stages, the prognosis is favourable, with a five-year survival rate reaching 90% [4].

Current guidelines recommend that individuals over 45 years old should undergo CRC screening to reduce CRC-related incidence and mortality [5,6,7]. Many countries and regions, such as Korea, America and China, have implemented CRC screening programs [8, 9]. The faecal occult blood test (FOBT)/faecal immunochemical test (FIT) and colonoscopy are the two most common screening tools [10]. However, extensive screening programs with colonoscopy have not been implemented in some countries due to resource and staffing constraints [11, 12]. FIT is relatively simple and inexpensive, but its sensitivity and specificity are limited, which may lead to missed diagnosis in high-risk persons [13]. Therefore, a risk stratification strategy is needed for persons undergoing CRC screening to make the most of the limited resources and improve the efficiency of screening.

Multiple risk scoring systems have been introduced in various countries for CRC screening [14,15,16]. In China, the high-risk factor questionnaire (HRFQ) was proposed for risk stratification and was based on the CRC screening project in two counties of Zhejiang Province [17]. Subsequently, the combination of the HRFQ and FIT has been adapted by the Chinese Ministry of Health since 2006 [18] and implemented in many cities across China, including Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Tianjin, and significant results have been achieved [19,20,21,22]. In this screening procedure, subjects with positive FIT or HRFQ were classified as high risk and recommended to undergo colonoscopy [21]. Nevertheless, previous studies have found that adherence to further colonoscopy follow-up was generally low, and less than 30% of high-risk participants underwent colonoscopy [20, 23]. The current risk stratification has a high sensitivity but a high false positive rate, leading to unnecessary colonoscopy, which results in doubts about the effectiveness of screening and decreases compliance [24]. In addition, some of the latest well-documented risk factors, such as smoking status, alcohol intake and BMI, were not included in the current HRFQ and may affect the discriminatory ability of the screening procedure [25].

In this study, we developed a risk scoring model for predicting colorectal lesions based on the high-risk population in the Tianjin CRC screening programme from 2012–2020. Our findings may help to improve the commonly used risk stratification methods, promote adherence to colonoscopy and increase the efficiency of CRC screening in China.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted at Tianjin Union Medical Center as a part of the Tianjin CRC screening programme. The Tianjin CRC screening programme was established in 2012 by the government, and it already provided free CRC screening for more than 6 million residents aged > 40 years in Tianjin from 2012–2020. A two-step method similar to that of Jiashan County [18, 26] was applied in the CRC screening programme, in which HRFQ and FIT were used for initial screening, and subjects with any positive HRFQ or FIT were recommended to undergo colonoscopy screening. The population of this study was a subset of the screening programme, and this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Union Medical Center.

Study participants

This study retrospectively analysed the data obtained from the prospective screening programme. The inclusion criteria included the following: (1) Participants defined as high-risk in initial screening, with positive FIT (ABON, China) or (and) positive-HRFQ. Positive HRFQ was defined as subjects meeting any of following conditions: (a) history of any cancer or colorectal polyps; (b) history of CRC in first-degree relatives; (c) history of two or more of the following symptoms: chronic diarrhoea, chronic constipation, serious unhappy life events such as death among first-degree relatives, mucus or bloody stool, chronic appendicitis or appendectomy, chronic cholecystitis or cholecystectomy; (2) those who underwent subsequent colonoscopy after being identified as high risk by FIT or (and) HRFQ; and (3) those who wished to participate and signed informed consent form. Subjects with a history of CRC were excluded from this study.

Colonoscopy procedures

All endoscopic examinations were performed in the hospital by experienced endoscopists who had at least 5 years of experience and were all board certified to perform endoscopy. All abnormal findings were confirmed by expert gastrointestinal pathologists following up-to-date clinical guidelines. Only high-quality colonoscopies were included, with adequate bowel preparation, photo documentation of caecal landmarks, and a withdrawal time > 6 min.

Colorectal lesions were classified as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, ulcer, adenoma, and CRC [20]. ACN was defined as CRC or advanced adenoma ≥ 10 mm in diameter or with villous components or high-grade dysplasia. CRN was defined as cancer or any adenoma.

Measurements and definitions

In this study, smoking status was categorized as never smoker and current or past smoker. Alcohol consumption was categorized as never or occasional alcohol intake and weekly alcohol intake. Regular exercise was defined as at least 30 min of exercise more than once weekly over the last year; otherwise, it was classified as ‘physical inactivity’. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 according to Chinese criteria [27]. Educational level was categorized as low (primary education or below), intermediate (secondary education, high education or lower vocational education) and high (higher vocational education, university or above).

Development of risk scores

The association between the prevalence of ACN and clinical risk factors was assessed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. The risk factors examined included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol intake and physical activity. All risk factors with p values less than 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in the binary logistic regression model for ACN. A scoring model for predicting ACN was developed based on the results of multivariate analysis, and each variable was assigned a weight using the respective adjusted OR rounded to the nearest integer. The final score of each participant was the sum of scores for each risk factor.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (V.4.1.2). The prevalence of CRN, ACN and CRC was calculated in participants stratified by clinical parameters and assessed with the chi-square test. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI), beta-confidence and standard error of each variable were calculated by a logistic regression model. The prevalence of ACN was evaluated according to each score, and then screened individuals were divided into three subgroups according to the final scores: “low risk (LR)”, “moderate risk (MR)” and “high risk (HR)”. A bootstrapping test with 1000 replicates was performed to internally validate the new scoring model. To evaluate the discriminatory capability of the model, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted, and c-statistics were calculated. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

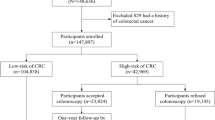

The population-based CRC screening process is shown in Fig. 1. The clinical parameters and colorectal lesions of the participants are summarized in Table 1. There were 29,504 high-risk participants enrolled in this study, with 20,299 (68.8%) having a positive FIT and 13,460 (45.6%) having positive HRFQ results. Of these, 14,677 (49.7%) individuals were found to have CN, including 2324 (7.9%) diagnosed with ACN. The average age of all subjects was 63.53 years (SD 7.47), 15,710 (53.2%) were female participants, 16.0% had a BMI greater than 28 kg/m2, and 24.4% were current or past smokers.

Univariate and multivariate predictors of ACN

The association between the prevalence of ACN and risk factors evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses is shown in Table 2. From multivariate analysis adjusted for educational level and marital status, each 10-year increase in age from 50 years onwards (OR = 2.14–5.52), male sex (OR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.49–1.79), BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.08–1.33), ever smoking (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.06–1.29) and weekly alcohol intake (OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.08–1.38) were significantly correlated with the presence of ACN, while physical inactivity showed no correlation with ACN in univariate or multivariate analysis.

Development of the risk score

A scoring model for predicting ACN was developed, and points were assigned to relative risk factors as follows (Table 3): male sex (2), female sex (0), age < 50 years (0), age 50–60 years (2), age 60–70 years (4), age ≥ 70 years (6), BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 (1), BMI < 28 kg/m2 (0), current or past smoking (1), never smoking (0), weekly alcohol intake (1), and never or occasional alcohol intake (0). The scoring system ranged from 0–11, and the points were weighted according to ORs from the multivariate analysis rounding to the nearest whole number. The number of participants with different scores and the prevalence of ACN by scores are presented in Table 4.

Discriminatory ability and reliability of the risk score

Subjects were divided into three risk tiers: LR, low risk (score 0–3); MR, moderate risk (score 4–6); and HR, high risk (score 7–11). The proportions of LR, MR and HR were 17.9% (5267/29504), 53.8% (15,888/29504) and 28.3% (8349/29504), respectively. Subjects with MR had a prevalence of ACN similar to the overall prevalence (7.1% vs. 7.9%). Compared with subjects with LR, those with MR and HR had ORs of 2.47 (2.09–2.93) and 4.59 (3.86–5.44), respectively (Table 4). Furthermore, internal validation showed a c-statistic of 0.64 (95% CI = 0.63–0.65) in the 1000 bootstrapped samples, which showed that it has a relatively stable risk-stratification ability.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a scoring system for further risk stratification of a CRC high-risk population classified by the current screening procedure. The risk score derived from the logistic regression model included five well-recognized risk factors (sex, age, BMI, alcohol intake and smoking status) that were not included in the current screening tools. The scoring model performed well, and the ACN risk was found to be 2–sixfold higher in subjects with scores over 6 than in other individuals. Given the high false positive rate and low adherence to colonoscopy in participants, our findings have the potential to serve as a powerful complement to existing screening strategies and improve the effectiveness of screening programs.

After risk stratification by this scoring system, the prevalence of ACN in the high-risk group increased from 7.9% to 12.4%. Colonoscopy resources remain limited across China, and the application of this scoring system could take better advantage of these resources, which may help increase the discovery rate of colorectal lesions and help more patients with colorectal neoplasia diagnosed at an early stage. Integrating this scoring model with current screening methods could improve the effectiveness of screening programs, which will make populations more trusting of the results of risk stratification and more willing to receive colonoscopy tests.

Multiple scoring models for predicting ACN have been constructed in previous studies, containing common variables (sex, age, smoking status and family history) and subtle differences in other factors [14, 15, 28, 29]. Sekiguchi et al. proposed a scoring system for risk stratification in Japanese average-risk populations using five risk factors, including sex, age, family history, BMI and smoking history, which stratified screened subjects into three risk groups [14]. The most well-known Asia–Pacific Colorectal Screening score (APCS) also incorporated age, sex, family history and smoking to predict the risk for ACN, which was created based on the population from 11 countries in Asia [28], and the factors included in our scoring model were similar to those of previous studies. In addition, some well-recognized factors, such as family CRC history and personal cancer history, were not considered in our score, since they were included in the HRFQ and have been evaluated before.

The predictive ability of our score was consistent with that of previous studies; participants with higher scores had a significantly higher risk of colorectal neoplasia. The prevalence of ACN in our study was 12.2%, which was slightly higher than that in studies conducted in Japan (10.2%) [14] and the USA (9.0%) [16]. In addition, participants with high and moderate risk had a 4.59- and 2.40-fold higher risk of ACN, respectively, than those with low risk, which was consistent with the results of the APCS study [28]. The c-statistic of this score was 0.64, superior to that established by Liang et al. (c-statistic = 0.62) [30] and comparable to multiple previous scoring systems [14, 15].

Previous studies mainly focused on average-risk asymptomatic populations [14, 28], while we pioneered to focus on a relatively high-risk population according to HRFQ and FIT screening. In mainland China, nearly every large-scale CRC screening programme has adapted a two-step procedure, using HRFQ as the first step and colonoscopy as the second step [19,20,21,22]. Nevertheless, the HRFQ was implemented by the Chinese Ministry of Health in 2006, and some newly identified factors were not included in it [18]. Thus, it is of vital importance to develop a scoring system incorporating the latest well-recognized neoplasia-related risk factors to improve the current imperfect HRFQ. For instance, male sex and older age were found to be associated with ACN in various studies [28, 31, 32].

Individuals with overweight and obesity account for at least 11% of CRC cases in Europe, and each 1-kg/m2 increase in BMI confers an additional risk of CRC (HR = 1.03) [33, 34]. Lee et al. reported that the prevalence of colorectal polyps was 3.5 times higher in current smokers than in never smokers [35]. Alcohol intake is a well-documented risk factor for CRC, and a recent meta-analysis based on 8 large-scale studies revealed that heavy consumption was associated with an increased risk of CRC [36, 37]. Moreover, the latest study in Lancet reported that the leading risk factors contributing to global cancer burden were smoking, alcohol use and high BMI [38]. The scoring models involving the factors above have been implemented in many countries, such as Korea [15], Japan [14] and the USA [29], and incorporating these factors into Chinese official CRC screening programmes will improve the effectiveness of screening and increase adherence to colonoscopy.

There were several limitations to this study. First, although we have done our best to analyse all CRC-related factors, some potential related factors, such as diabetes [39], dietary habits and lifestyle [40], were still not considered since the information was not collected. Second, external validation of this risk score was not performed due to the lack of external data. Third, most indicators were self-reported by participants, which may introduce recall bias. Only subjects who underwent colonoscopy were involved in this study, which may cause selection bias. Finally, this score was developed based on participants in Tianjin, and generalizability to other settings or cities should be done with caution.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we developed a scoring system for further risk stratification of a high-risk population classified by HRFQ and FIT that could identify very high-risk populations with colorectal neoplasia. Combining this risk score with current Chinese screening methods may improve the effectiveness of CRC screening and adherence to colonoscopy.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data confidentiality requirements of Tianjin Health Commission but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(7):783–91.

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Schoen RE. Association of Colonoscopy Adenoma Findings With Long-term Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2021–31.

Moody L, Dvoretskiy S, An R, Mantha S, Pan YX. The Efficacy of miR-20a as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(8):1111.

Ladabaum U, Dominitz JA, Kahi C, Schoen RE. Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):418–32.

Qaseem A, Crandall CJ, Mustafa RA, Hicks LA, Wilt TJ, Forciea MA, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Asymptomatic Average-Risk Adults: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):643–54.

Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965–77.

Navarro M, Nicolas A, Ferrandez A, Lanas A. Colorectal cancer population screening programs worldwide in 2016: An update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(20):3632–42.

Kaminski MF, Robertson DJ, Senore C, Rex DK. Optimizing the Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening Worldwide. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):404–17.

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687–96.

Young GP. Population-based screening for colorectal cancer: Australian research and implementation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(Suppl 3):S33-42.

Shim JI, Kim Y, Han MA, Lee HY, Choi KS, Jun JK, et al. Results of colorectal cancer screening of the national cancer screening program in Korea, 2008. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42(4):191–8.

Dekker E, Rex DK. Advances in CRC Prevention: Screening and Surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(7):1970–84.

Sekiguchi M, Kakugawa Y, Matsumoto M, Matsuda T. A scoring model for predicting advanced colorectal neoplasia in a screened population of asymptomatic Japanese individuals. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(10):1109–19.

Park CH, Kim NH, Park JH, Park DI, Sohn CI, Jung YS. Individualized colorectal cancer screening based on the clinical risk factors: beyond family history of colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88(1):128–35.

Wong MC, Lam TY, Tsoi KK, Hirai HW, Chan VC, Ching JY, et al. A validated tool to predict colorectal neoplasia and inform screening choice for asymptomatic subjects. Gut. 2014;63(7):1130–6.

Zheng GM, Choi BC, Yu XR, Zou RB, Shao YW, Ma XY. Mass screening for rectal neoplasm in Jiashan County. China J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(12):1379–85.

Cai SR, Zhang SZ, Zhu HH, Huang YQ, Li QR, Ma XY, et al. Performance of a colorectal cancer screening protocol in an economically and medically underserved population. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(10):1572–9.

Wu WM, Wang Y, Jiang HR, Yang C, Li XQ, Yan B, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening Modalities in Chinese Population: Practice and Lessons in Pudong New Area of Shanghai. China Front Oncol. 2019;9:399.

Chen W, Zhang W, Liu H, Liang Y, Zhou Q, Li Y, et al. How spatial accessibility to colonoscopy affects diagnostic adherences and adverse intestinal outcomes among the patients with positive preliminary screening findings. Cancer Med. 2020;9(12):4405–19.

Huang W, Liu G, Zhang X, Fu W, Zheng S, Wu Q, et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening protocols in urban Chinese populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109150.

Zhang M, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Jing H, Wei L, Li Z, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening With High Risk-Factor Questionnaire and Fecal Immunochemical Tests Among 5, 947, 986 Asymptomatic Population: A Population-Based Study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:893183.

Lin G, Feng Z, Liu H, Li Y, Nie Y, Liang Y, et al. Mass screening for colorectal cancer in a population of two million older adults in Guangzhou, China. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):10424.

Esserman LJ, Thompson IM Jr, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. JAMA. 2013;310(8):797–8.

Wu WM, Gu K, Yang YH, Bao PP, Gong YM, Shi Y, et al. Improved risk scoring systems for colorectal cancer screening in Shanghai. China Cancer Med. 2022;11(9):1972–83.

Zheng S, Chen K, Liu X, Ma X, Yu H, Chen K, et al. Cluster randomization trial of sequence mass screening for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(1):51–8.

Lv F, Cai X, Lin C, Hong T, Zhang X, Wang Z, et al. Sex differences in the prevalence of obesity in 800,000 Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Connect. 2021;10(2):139–45.

Yeoh KG, Ho KY, Chiu HM, Zhu F, Ching JY, Wu DC, et al. The Asia-Pacific Colorectal Screening score: a validated tool that stratifies risk for colorectal advanced neoplasia in asymptomatic Asian subjects. Gut. 2011;60(9):1236–41.

Imperiale TF, Monahan PO, Stump TE, Ransohoff DF. Derivation and validation of a predictive model for advanced colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. Gut. 2021;70(6):1155–61.

Liang L, Liang Y, Li K, Qin P, Lin G, Li Y, et al. A risk-prediction score for colorectal lesions on 12,628 participants at high risk of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2022;10(1):goac002.

Tao S, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Development and validation of a scoring system to identify individuals at high risk for advanced colorectal neoplasms who should undergo colonoscopy screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):478–85.

Imperiale TF, Monahan PO, Stump TE, Glowinski EA, Ransohoff DF. Derivation and Validation of a Scoring System to Stratify Risk for Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Asymptomatic Adults: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):339–46.

Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62(6):933–47.

Kroenke CH, Neugebauer R, Meyerhardt J, Prado CM, Weltzien E, Kwan ML, et al. Analysis of Body Mass Index and Mortality in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Using Causal Diagrams. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(9):1137–45.

Lee K, Kim YH. Colorectal Polyp Prevalence According to Alcohol Consumption, Smoking and Obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2387.

Cho E, Lee JE, Rimm EB, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL. Alcohol consumption and the risk of colon cancer by family history of colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):413–9.

McNabb S, Harrison TA, Albanes D, Berndt SI, Brenner H, Caan BJ, et al. Meta-analysis of 16 studies of the association of alcohol with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):861–73.

GBD 2019 Cancer Risk Factors Collaborators. The global burden of cancer attributable to risk factors, 2010-19: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;400(10352):563-91.

Ali Khan U, Fallah M, Tian Y, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Brenner H, et al. Personal History of Diabetes as Important as Family History of Colorectal Cancer for Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1103–9.

Bhopal RS. Diet and Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1726–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This research was supported by the Key R&D Projects in the Tianjin Science and Technology Pillar Program (Grant number 19YFZCSY00420), National key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2017YFC1700604), National key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2017YFC1700606), Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (21JCZDJC00060, 21JCYBJC00180 and 21JCYBJC00340), Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (Grant number TJYXZDXK-044A) and Tianjin Hospital Association Hospital Management Research Project (Grant number 2019ZZ07).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CZ conceived and designed the study and received funding. CZ, XZ and WC performed data acquisition and collection. ZY, SW, YL and ZL did data analysis and interpretations. ZY, YH, XL and WG prepared the first draft. HL, YW, QZ, HM, JW and XW critically revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Union Medical Center and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All methods were carried out in accordance with guidelines and regulations related to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Z., Wang, S., Liu, Z. et al. A risk scoring system for advanced colorectal neoplasia in high-risk participants to improve current colorectal cancer screening in Tianjin, China. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 466 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02563-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02563-9