Abstract

Background

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare protein-losing enteropathy characterized by the loss of proteins, lymphocytes, and immunoglobulins into the intestinal lumen. Increasing evidence has demonstrated an association between PIL and lymphoma.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old man with a 20-year history of abdominal distension and bilateral lower limb edema was admitted. Laboratory investigations revealed lymphopenia, hypoalbuminemia, decreased triglyceride and cholesterol level. Colonoscopy showed multiple smooth pseudo polyps in the ileocecal valve and terminal ileum and histological examination showed conspicuous dilation of the lymphatic channels in the mucosa and submucosa. A diagnosis of PIL was made. Three years later colonoscopy of the patient showed an intraluminal proliferative mass in the ascending colon and biopsy examination confirmed a malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Then the patient was been underwent chemotherapy, and his clinical condition is satisfactory.

Conclusion

Our report supports the hypothesis that PIL is associated with lymphoma development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare disease manifested by the loss of proteins, lymphocytes, and immunoglobulins into the intestinal lumen [1], which in turn leads to the suppression of both the humoral and cellular immune systems [2]. Since the first description in 1961 [3], nearly 200 cases of PIL cases have been reported globally [4]. However, with the improvement of endoscopic technology, especially the enteroscopy, PIL is increasingly been recognized and the prevalence might be underestimated. And increasing evidence has demonstrated an association between PIL and lymphoma [2, 5,6,7,8,9,10]. Here, we report a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurring 23 years after the onset of PIL, and conduct a systematic review of the literature on lymphoma and PIL.

Case presentation

In January 2016, a 54-year-old man with a 20-year history of abdominal distension and bilateral lower limb edema was admitted to our hospital. The patient reported no history of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, kidney disease, thyroid disease, or hepatitis. A physical examination confirmed the presence of abdominal distension and pitting edema in both lower limbs. Laboratory investigations revealed the following: lymphopenia (lymphocyte count, 0.45*109/L; normal range 1.1–3.2*109/L), hypoalbuminemia (albumin, 15.8 g/L; normal range 40–55 g/L), decreased triglyceride level (0.36 mmol/L; normal range 0.4–1.8 mmol/L), decreased cholesterol level (2.47 mmol/L; normal range 3.6–6.5 mmol/L), and normal liver and kidney function. Abdominal computed tomography revealed a small amount of fluid and diffuse thickening of multiple small bowel loops (Fig. 1a, b). The patient then underwent colonoscopy, which revealed multiple smooth pseudo polyps in the ileocecal valve and terminal ileum (Fig. 1c, d). Biopsies were taken from ileocecal valve and terminal ileum to exclude lymphoma and intestinal lymphangiectasia. The lymphatic channels in the mucosa and submucosa were dilated conspicuously and D2-40 positive staining, a marker of lymphatic endothelial cells, was observed (Fig. 2). The diagnosis of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) was made, and the patient was immediately prescribed a low-fat, high-protein diet and medium-chain triglyceride supplementation.

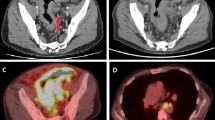

On May 5, 2019, the patient returned to our hospital with a right-sided inguinal hernia that had been present for 6 months. A physical examination showed a 3*3-cm mass in the right inguinal region. Abdominal computed tomography showed thickening of the ascending colon with luminal narrowing (Fig. 3a). Colonoscopy showed an intraluminal proliferative mass in the ascending colon (Fig. 3b). Biopsy examination confirmed a malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 3c, d). The tumor cells stained positive for CD20 (diffuse, strong), CD79a (diffuse+), Ki67 (90%), BCL6 (+), CD10 (weak, sun), BCL6 (+), and c-Myc (30%), and negative for CD5, cyclinD1, CD23, CD21, BCL2, MUM1, CD30, and p53 (wild type), which was consistent with a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In situ hybridization test showed that the tumor cells were negative for the Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER).

a Contrast-enhanced computed tomography and b colonoscopy show a mass lesion in the ascending colon. c A biopsy examination reveals a non-Hodgkin malignant lymphoma (hematoxylin and eosin staining; magnification, 400-fold magnification). d A biopsy examination reveals a non-Hodgkin malignant lymphoma (CD20 staining; magnification, 400-fold magnification)

Chemotherapy with the R-CHOP regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) was initiated. At the time of this writing, the patient continues to undergo chemotherapy, and his clinical condition is satisfactory, expect for hypoalbuminemia and bilateral lower limb edema.

Discussion and conclusion

PIL is a rare condition that is characterized by abnormally dilated intestinal lymphatic channels that leak lymphatic fluid into the gastrointestinal tract; this loss of lymphatic fluid eventually results in hypoproteinemia, hypogammaglobinemia, edema, and lymphocytopenia and other immune abnormalities [1]. PIL was first described in 1961 by Waldmann et al. [2]. The majority of patients with PIL have a benign prognosis, and therefore, the condition is usually diagnosed only late in life. The reported complications of PIL include malignant transformation, cutaneous warts, infections, and gelatinous transformation of the bone marrow [3]. Malignancy, especially lymphoma, as a complication is rarely reported.

In 1972, Waldmann et al. described the relationship between PIL and lymphoma for the first time; among the 50 PIL patients reviewed, 3 had malignant lymphoma [4]. In 1998, Gumà et al. first conducted a retrospective study of 8 patients with small intestinal lymphangiectasis complicated with lymphoma [5]. In 2000, Bouhnik et al. raised the hypothesis that PIL predisposes to lymphoma [6]. Wen et al. retrospectively reviewed 84 PIL patients, and found that 4 (5%) patients developed lymphoma; the mean time of lymphoma detection was 31 years after the PIL diagnosis [7].

We identified a total of 10 studies examining the correlation between PIL and lymphoma. The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients in these studies as well as the patient in the present study (n = 14) are summarized in Table 1 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. An analysis of the 14 reported cases of PIL-associated lymphoma revealed the following findings: (1) The time from PIL onset to lymphoma detection was 19.14 ± 12.29 years on average (range 3–45 years), and was > 10 years in the majority of patients (79%). (2) In 4 of the 14 patients, the presenting symptom of lymphoma was abdominal pain. This is consistent with the finding of Wen et al. that malignant complications in PIL patients may manifest as an urgent clinical presentation with abdominal pain [7]. The most common sites of PIL-associated lymphoma were the small intestine and stomach, although breast, bone, and retroperitoneal involvement were also observed.

The mechanism underlying the development of lymphoma in patients with PIL may be related to the continuous loss of lymphocytes and immunoglobulins through the intestinal lumen, leading to immune deficiency and weakened immune surveillance [15]. However, patients with PIL have also been reported to have a primary functional B-cell and/or helper T-cell deficiency, and the persistent loss of immunoglobulins and lymphocytes through lymph leakage results in a secondary immune deficiency in these patients [16].

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy dramatically improved the symptoms of both lymphoma and PIL in 4 of the 14 patients. This improvement may be attributable to the inclusion of glucocorticoids in combination chemotherapy regimens, which may have suppressed the inflammatory reactions that would otherwise have led to increased permeability of the intestinal lymphatic vessels [17]. Nevertheless, the PIL symptoms did not completely disappear after the lymphoma treatment in most patients.

In conclusion, PIL is a rare disease with an unclear etiology. A growing body of evidence indicates that the link between PIL and lymphoma is not merely coincidental, and that PIL is a potent predisposing factor for lymphoma after 10 or more years. In some PIL patients, the malignant lesions were confined to the gastrointestinal system, while in others, they were extra-intestinal. The pathophysiological explanation for the association between PIL and lymphoma remains unclear.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PIL:

-

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia

- EBER:

-

Epstein-Barr encoding region

- CVP:

-

Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone

- VCP:

-

Vincristine, chlorambucil, and prednisone

- AVmCP:

-

Adriamycin, teniposide, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone

- CHOP:

-

Cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone

- PACOB:

-

Prednisolone, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and bleomycin

- R-CHOP:

-

Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicine, vincristine, and prednisone

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- DLBC:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

References

Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:5.

Bouhnik Y, Etienney I, Nemeth J, Thevenot T, Lavergne-Slove A, Matuchansky C. Very late onset small intestinal B cell lymphoma associated with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia and diffuse cutaneous warts. Gut. 2000;47:296–300.

Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, Davidson JD, Gordon RS Jr. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197–207.

Wen J, Tang Q, Wu J, Wang Y, Cai W. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: four case reports and a review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3466–72.

Gumà J, Rubió J, Masip C, Alvaro T, Borràs JL. Aggressive bowel lymphoma in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia and widespread viral warts. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1355–6.

Alshikho MJ, Talas JM, Noureldine SI, Zazou S, Addas A, Kurabi H, Nasser M. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: insights on management and literature review. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:512–22.

Immunodeficiency Disease and Malignancy. Various immunologic deficiencies of man and the role of immune processes in the control of malignant disease. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:605–28.

Ward M, Le Roux A, Small WP, Sircus W. Malignant lymphoma and extensive viral wart formation in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia and lymphocyte depletion. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:753–7.

Broder S, Callihan TR, Jaffe ES, DeVita VT, Strober W, Bartter FC, Waldmann TA. Resolution of longstanding protein-losing enteropathy in a patient with intestinal lymphangiectasia after treatment for malignant lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:166–8.

Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 8–1984. An elderly woman with protein-losing enteropathy and pleural effusions. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:512–20.

Herait P, Gisselbrecht C, Ferme C, Jian R, Modigliani R, Griscelli C, Hervio P, Marty M, Boiron M. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma arising in a case of Waldmann’s intestinal lymphangiectasis. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1985;27:299–302.

Shpilberg O, Shimon I, Bujanover Y, Ben-Bassat I. Remission of malabsorption in congenital intestinal lymphangiectasia following chemotherapy for lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;11:147–8.

Laharie D, Degenne V, Laharie H, Cazorla S, Belleannee G, Couzigou P, Amouretti M. Remission of protein-losing enteropathy after nodal lymphoma treatment in a patient with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1417–9.

Prasad D, Srivastava A, Tambe A, Yachha SK, Sarma MS, Poddar U. Clinical profile, response to therapy, and outcome of children with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dig Dis. 2019;37:458–66.

Strober W, Wochner RD, Carbone PP, Yachha SK, Sarma MS, Poddar U. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: a protein-losing enteropathy with hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphocytopenia and impaired homograft rejection. J Clin Investig. 1967;46:1643–56.

Weiden PL, Blaese RM, Strober W, Block JB, Waldmann TA. Impaired lymphocyte transformation in intestinal lymphangiectasia: evidence for at least two functionally distinct lymphocyte populations in man. J Clin Investig. 1972;51:1319–25.

Fleisher TA, Strober W, Muchmore AV, Broder S, Krawitt EL, Waldmann TA. Corticosteroid-responsive intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to an inflammatory process. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:605–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China and the project No.:81800543, mainly to cover the cost of follow-up service fee and part of pathological section fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DH collected clinical data and performed the follow up; CX and RW revised the manuscript; JZ wrote the manuscript; XG collected pathological data; XJ supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Qingdao Municipal Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, D., Cui, X., Ren, W. et al. A case of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. BMC Gastroenterol 21, 461 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01997-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01997-x