Abstract

Background

Ectopic pancreas (EP) is defined as pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomical or vascular communication with the normal body of the pancreas. Despite improvements in diagnostic endoscopy and imaging studies, differentiating ectopic pancreatic tissue from gastric submucosal diseases remains a challenge.

Case presentation

Here, we present a case of a 44-year-old woman with severe epigastric pain. Initially, gastric lymphangioma was highly suspected due to a well-demarcated protruding mass with a large size that occurred in the submucosal layer of the gastric antrum and appeared as a cystic lesion. The final correct diagnosis of gastric EP was made during surgery.

Conclusion

Gastric EP with serous oligocystic adenoma appearing as a giant gastric cyst is extremely rare. The difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis and differential diagnosis is highlighted, which may provide additional clinical experience for the diagnosis of EP with serous oligocystic adenoma in the stomach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ectopic pancreas (EP) refers to healthy pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomical, vascular or neural communication with the normal pancreas; EP was probably first described in the eighteenth century when it was found in an ileal diverticulum [1]. EP can be detected in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, biliary system, liver, lung, mediastinum, and brain [1,2,3,4]. In the GI tract, the most common location for its presence is the stomach, followed by the duodenum (25–35%) and jejunum (16%) [1,2,3,4]. EP is usually found incidentally and is asymptomatic; however, it may become symptomatic when complicated by inflammation, bleeding, obstruction or malignant transformation [3,4,5,6]. Generally, it is difficult to make the correct pathological diagnosis from a typical endoscopic mucosal biopsy to distinguish EP from other gastric submucosal diseases. Herein, we report the case of a 44-year-old female with ectopic pancreas and serous oligocystic adenoma in the gastric antrum that mimicked a gastric lymphangioma.

Case presentation

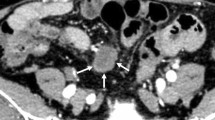

A 44-year-old female was admitted to our hospital due to epigastric pain with a duration of 6 months. There was no obvious cause of the paroxysmal dull abdominal pain when the pain was intense, radiating to the back. There was no history of loss of appetite, postprandial vomiting or gastrointestinal bleeding. Proton pump inhibitors were started but did not relieve the symptoms. Physical examination and her routine laboratory investigations were unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) identified a 5.8 * 3.9 cm epigastric mass that appeared to be a heterogeneous cystic and solid submucosal tumor arising from the thick posterior wall of the antrum proximal to the pylorus (Fig. 1a). Enhanced CT displayed irregular mixed cystic and solid lesions with thick walls and intracystic fluid. In the arterial phase, the solid part was unevenly enhanced, and the thick wall of cystic cavity was obviously enhanced until the venous phase (Fig. 1b, c). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a lesion elevated from the submucosa that was located from the posterior wall of the gastric antrum to the gastric angle with normal overlying mucosa (Fig. 2a). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) noted a smooth 5.5 cm + 3.8 cm mixed cystic and solid anechoic lesion in the submucosal layer, partially in the muscularis propria and serosa (Fig. 2b); the cystic wall became thicker when approaching the pylorus (Fig. 2c), with features suggestive of lymphangioma. Because of the size, the unknown pathology, and its involvement of the antrum whereby an attempt at local resection would have markedly narrowed the antrum, a decision was made to perform a distal gastrectomy. Clear transparent fluid was found in this cystic mass when opened in the pathology laboratory.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and EUS images of EP. a Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a lesion elevated from the submucosa that was located from the front wall of the gastric antrum to the gastric angle with normal overlying mucosa. b EUS noted a smooth 5.5 * 3.8 cm cystic and solid anechoic lesion in the submucosal layer, and the cystic wall became thicker when approaching the pylorus (c)

Histopathologic examination of the resected mass showed aberrant pancreatic tissues, including numerous acini, few ducts and islet cells involving the submucosa, muscularis propria and serosa; furthermore, the cysts were lined with a single layer of short columnar or cubic serous epithelia with clear cytoplasm, and all of these histological features supported a final diagnosis of EP with serous oligocystic adenoma (SOA) (Fig. 3a–i). The postoperative course was uneventful, and she has been asymptomatic with no recurrence for 18 months to date.

Histology of the surgical specimen. a Image of the surgical specimen. Numerous acini (b), few ducts (d) and islet cells (h) were found in the submucosa, muscularis propria and serosa. Cysts were lined by a single layer of short columnar or cubic serous epithelia (g). c Is a higher magnification image of b; e, f are higher magnification images of d; h, i are higher magnification images of g. b, d Represent slide 9 in a, and g is slide 5 in a. Blue arrows indicate EP tissues, and yellow arrows indicate higher magnification lesions. Scale bars represent 200 μm (a, b, d, g), 100 μm (c, e, f), and 50 μm (h, i)

Discussion and conclusions

EP is defined as pancreatic tissue that lacks anatomical or vascular communication with the normal body of the pancreas [7, 8]. Generally, the most common heterotopic site is the stomach, including the antrum and prepyloric region on the greater curvature or posterior wall; EP is usually found incidentally and is asymptomatic. However, it may become symptomatic when complicated by inflammation, bleeding, obstruction or malignant transformation [3,4,5]. Symptoms are dependent upon the anatomical location and the size of the lesion. Generally, lesions greater than 1.5 cm in diameter are more likely to cause symptoms [9], and pain is one of the most common symptoms [10]. In this case, a middle-aged woman with epigastric pain, a 5.8 * 3.9 cm cystic and solid lesion with a thick gastric wall was detected by CT and EUS. One possible explanation for the pain might be associated inflammation of the involved tissue as reported [10], but we didn’t have the direct evident to have any inflammatory sign. Therefore, reason of the pain was unknown.

A previous report indicated that EP often localizes in the submucosa, muscularis mucosa, and serosa, with distributions of 73%, 17% and 10%, respectively [1], sometimes involving through all of these layers [1]. Generally, we can make a clinical diagnosis of EP with a size less than 2 cm by upper endoscopy and EUS. However, for a giant EP, although imaging studies such as CT, radiographic contrast studies, EUS, and upper endoscopy are of assistance in the initial assessment of patients, it is still difficult to make a correct pathological diagnosis from endoscopic biopsy to distinguish EP from other gastric submucosal diseases [1, 10], which is the reason for operative treatment [10]. The final correct diagnosis is made from the pathological diagnosis of surgical specimens, and four types of pathological classifications of EP have been identified by the groups of Heinrich and Gaspar-Fuentes: type I) typical pancreatic tissue with ducts, acini and islet cells; type II) numerous acini, few ducts, and no islet cells; type III) numerous ducts, few to no acini and no islet cells [11]; and type IV) endocrine islets without exocrine pancreatic tissue [12].

In this case, due to the large size and location of the lesion in the submucosa, the difficulty of endoscopic treatment, as well as the needs of patient, distal gastrectomy and Billroth II reconstruction were performed by laparoscopy. Histological analysis showed that numerous acini, few ducts and some endocrine islets were found in the submucosa, muscularis propria and serosa; thus, a type I lesion was considered according to the Heinrich and Gaspar-Fuentes classification. Previous studies have reported that cystic changes can be seen in EP tissue and that retention cysts are usually small (less than 1–2 cm in size) and lined by a single layer of normal pancreatic epithelium, whereas pseudocysts are usually larger with walls that lack an epithelial lining [13, 14]. Furthermore, pancreatic cysts are classified as neoplastic or nonneoplastic. Neoplastic cysts include serous cystadenomas (SCA), solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), and cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Nonneoplastic cysts include simple cysts, lymphoepithelial cysts, and mucinous nonneoplastic cysts [15, 16]. In detail, serous cystic neoplasms (SCN) include SCA, VHL-associated serous cystic neoplasm, serous cystadenocarcinoma, and cystic neuroendocrine neoplasms [17]. SCA of the pancreas are uncommon benign neoplasms, which are composed of epithelial cells that produce serous fluid and show evidence of ductular differentiation, which are subdivided into serous micro cystic (glycogen-rich), and serous oligocystic adenoma (SOA) [17, 18]. SOA is defined as cystic epithelial neoplasms composed of ductular-type epithelial cells that produce a clear watery fluid, not contained mucinous, bilious and hemorrhagic. Morphologically, SOA is over 2 cm in size, and anechoic lesion was detected by EUS [18]. Gross pathology often demonstrates a giant cyst filled with serous fluid, by histology, the cysts are lined by a single layer of cuboidal or flattened epithelial cells with clear cytoplasm, and the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain is positive owing to their intracytoplasmic glycogen. In our case, pathological analysis demonstrated that the cyst was lined by a single layer of short columnar or cubic serous epithelia with clear cytoplasm, as well as numerous acini and few ducts in the submucosa, muscularis propria and serosa, which strongly supported a final diagnosis of EP with SOA. EP with SOA appearing as a giant gastric cyst is relatively rare, providing a novel and atypical case for EP.

The main differential diagnoses with EP include gastrointestinal stromal tumors, gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors, gastric carcinoids, lymphomas and gastric carcinomas [3, 19, 20]. Moreover, gastric cystic lesions needed to be distinguished from different diseases, including gastric diverticula, gastric duplication, and gastritis profunda cystica. However, initially, gastric lymphangiomas have been highly suspected before surgery for the following reasons: most lymphangiomas manifest as cystic or cavernous lesions [19]. In our case, a well-demarcated protruding mass with a large size occurred in the submucosal layer of the gastric antrum and appeared as a cystic lesion, and except for severe epigastric discomfort, there were no abnormal laboratory findings or clinical signs, which may be explained as infection in cystic lesions because enhanced CT displayed irregular cystic and solid lesions with thick walls and flocculent contents, and the cystic wall was obviously thicker and enhanced from the arterial to the venous phase.

Additionally, gastric lymphomas can present with pain [21,22,23]. Endoscopically, lymphangioma presents as a submucosal tumor with normal overlying mucosa [23]. EUS images showing lesions composed of anechoic and lobulated structures located predominantly in the submucosa are also characteristic of gastric lymphangioma [22,23,24,25,26], but these lesions have very thin walls and little stromal or thickened wall Therefore, it is necessary to clarify gastric lymphangioma in the differential diagnosis of EP in clinical work.

In summary, gastric EP with serous oligocystic adenoma appearing as a giant gastric cyst is extremely rare. Despite improvements in diagnostic endoscopy and imaging studies, it remains a challenge to differentiate ectopic pancreatic tissue from gastric submucosal diseases, such as gastric lymphangioma. This study may provide additional clinical experience for the diagnosis of EP in the stomach.

Availability of data and materials

All information about the patient come from the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University. The data used and analyzed during the current study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EP:

-

Ectopic pancreases

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasound

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

- MCN:

-

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid-Schiff

- SCA:

-

Serous cystadenomas

- SCN:

-

Serous cystic neoplasms

- SOA:

-

Serous oligocystic adenoma

- SPN:

-

Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm

References

Christodoulidis G, Zacharoulis D, Barbanis S, Katsogridakis E, Hatzitheofilou K. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(45):6098–100.

Filip R, Walczak E, Huk J, Radzki RP, Bienko M. Heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the gastric cardia: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16779–81.

Kim JY, Lee JM, Kim KW, Park HS, Choi JY, Kim SH, et al. Ectopic pancreas: CT findings with emphasis on differentiation from small gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Radiology. 2009;252(1):92–100.

Cazacu IM, Luzuriaga Chavez AA, Nogueras Gonzalez GM, Saftoiu A, Bhutani MS. Malignant transformation of ectopic pancreas. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(3):655–68.

Emerson L, Layfield LJ, Rohr LR, Dayton MT. Adenocarcinoma arising in association with gastric heterotopic pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87(1):53–7.

Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I, Tsiaousis P, Panagiotopoulou K, Paraskevas G, Argiriadou H, et al. Carcinoma developing in ectopic pancreatic tissue in the stomach: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):249.

Mulholland KC, Wallace WD, Epanomeritakis E, Hall SR. Pseudocyst formation in gastric ectopic pancreas. JOP. 2004;5(6):498–501.

Zhang L, Sanderson SO, Lloyd RV, Smyrk TC. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in heterotopic pancreas: evidence for the progression model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(8):1191–5.

Armstrong CP, King PM, Dixon JM, Macleod IB. The clinical significance of heterotopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1981;68(6):384–7.

Ormarsson OT, Gudmundsdottir I, Marvik R. Diagnosis and treatment of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Surg. 2006;30(9):1682–9.

Matsuki M, Gouda Y, Ando T, Matsuoka H, Morita T, Uchida N, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising from aberrant pancreas in the stomach. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(6):652–6.

Gaspar Fuentes A, Campos Tarrech JM, Fernandez Burgui JL, Castells Tejon E, Ruiz Rossello J, Gomez Perez J, et al. Pancreatic ectopias. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1973;39(3):255–68.

Sarsenov D, Tirnaksiz MB, Dogrul AB, Tanas O, Gedikoglu G, Abbasoglu O. Heterotopic pancreatic pseudocyst radiologically mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int Surg. 2015;100(3):486–9.

Campbell F, Verbeke CS. Pathology of the pancreas—a practical approach. London: Springer; 2013.

Patel N, Mukherjee S. Pancreatic cysts. In: Statpearls. Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing StatPearls Publishing LLC. 2020.

Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, Masica DL, Jiao Y, Kinde I, Blackford A, Raman SP, Wolfgang CL, Tomita T, et al. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1501–10.

Reid MD, Choi H, Balci S, Akkas G, Adsay V. Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2014;31(6):475–83.

Santos LD, Chow C, Henderson CJA, Blomberg DN, Merrett ND, Kennerson AR, Killingsworth MC. Serous oligocystic adenoma of the pancreas: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with ultrastructural findings. Pathology. 2002;34(2):148–56.

Diaconu C, Ciocirlan M, Jinga M, Costache RS, Constantinescu G, Ilie M, et al. Ectopic pancreas mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumor in the stomach fundus. Endoscopy. 2018;50(7):E186-e187.

Subasinghe D, Sivaganesh S, Perera N, Samarasekera DN. Gastric fundal heterotopic pancreas mimicking a gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST): a case report and a brief review. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:185.

Zhu H, Wu ZY, Lin XZ, Shi B, Upadhyaya M, Chen K. Gastrointestinal tract lymphangiomas: findings at CT and endoscopic imaging with histopathologic correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(6):662–8.

Li QY, Xu Q, Fan SF, Zhang Y. Gastric haemolymphangioma: a literature review and report of one case. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1010):e31–4.

Tsai CY, Wang HP, Yu SC, Shun CT, Wang TH, Lin JT. Endoscopic ultrasonographic diagnosis of gastric lymphangioma. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(6):333–5.

Balderramo DC, Di Tada C, de Ditter AB, Mondino JC. Hemolymphangioma of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2003;27(2):197–9.

Kosmidis I, Vlachou M, Koutroufinis A, Filiopoulos K. Hemolymphangioma of the lower extremities in children: two case reports. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:56.

Bosdure E, Mates M, Mely L, Guys JM, Devred P, Dubus JC. Cystic intrathoracic hemolymphangioma: a rare differential diagnosis of acute bronchiolitis in an infant. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12(2):168–72.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the department of pathology and radiology in our hospital for providing information.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant numbers: 81860103, 82070536 and 82073087], the Outstanding Scientific Youth Fund of Guizhou Province [Grant number: 2017-5608], the Joint Funds of the Science and Technology Foundation of Guizhou Province [Grant number: J[2013]13]. The role of the funding: Grant numbers 81860103, 82070536, 82073087, 2017-5608 and J[2013]13: designing of the study and data collection; Grant numbers: 81860103 and 82070536: writing and revising the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XML, BGT, and HCW wrote the manuscript; XML, BGT, XLW and HCW diagnosed and treated the patient; all authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript, all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient. Verbal and written consent was obtained for publication of the case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Wu, X., Tuo, B. et al. Ectopic pancreas appearing as a giant gastric cyst mimicking gastric lymphangioma: a case report and a brief review. BMC Gastroenterol 21, 151 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01686-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01686-9