Abstract

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a very common functional bowel disorder. However, the difference of depression and anxiety comorbidities among different IBS subtypes is still not well evaluated. This study aims to investigate the difference in the level and prevalence of depression and anxiety among healthy controls and patients with different subtypes of IBS.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane library were searched systematically until August 17, 2020. Studies that investigated depression and/or anxiety levels or prevalence among different IBS-subtype patients measured at baseline or the same point were included. Network meta-analysis was conducted to analyze standardized mean difference (SMD) of anxiety and depression levels, and single arm meta-analysis was performed for prevalence of anxiety and depression among different IBS subtypes.

Results

Eighteen studies involving 7095 participants were included. Network meta-analyses results showed healthy controls had a lower level of depression than IBS with mixed symptoms of constipation and diarrhea (IBS-M) [SMD = − 1.57; 95% confidence interval (CI) − 2.21, − 0.92], IBS with constipation (IBS-C) (SMD = − 1.53; 95% CI − 2.13, − 0.93) and IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D)(SMD = − 1.41; 95% CI − 1.97, − 0.85), while no significant difference was found between IBS unclassified (IBS-U) and healthy controls (SMD = − 0.58; 95% CI − 2.15, 1.00). There was also no significant difference in the level of depression among different IBS subtypes patients. The results of anxiety were similar to depression. Ranking probability showed that IBS-M was associated with the highest level of depression and anxiety symptoms, followed by IBS-C/IBS-D and IBS-U. Single-arm meta-analysis showed IBS-C had the highest prevalence of depression (38%) and anxiety (40%), followed by IBS-D, IBS-M and IBS-U.

Conclusion

The results indicated that IBS-M was more likely to be associated with a higher level of depression and anxiety, and the prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBS-C was highest. The psychological screening and appropriate psychotherapy are needed for patients with IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M instead of IBS-U.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent, costly and potentially disabling functional bowel disorder characterized by recurrent abdominal pain or changes in bowel habits [1]. The global prevalence of IBS is estimated to be 11.2%, but regionally it varies between 1.1 and 45% of the general population [2], and IBS can impose a major cost burden on the healthcare services and society [3, 4]. The estimating annual cost per patient in U.S. is $742–$7547, and the annual cost is around $1.7 billion to $10 billion in direct medical costs [3, 5]. On the basis of the Rome IV criteria, IBS is classified into four subtypes IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with mixed symptoms of constipation and diarrhea (IBS-M), or IBS unclassified (IBS-U) according to patients’ reports of the proportion of time they have hard or lumpy stools versus loose or watery stools [6].

IBS patients often suffer from a high burden of depression and anxiety [7]. According to a clinic-based study, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome patients is 37.1 and 31.4% respectively [8]. However, the pathophysiology of IBS is still unclear. “Biopsychosocial Conceptual Model” and “Multi-Dimensional Clinical Profile” are emphasized according to the Rome IV criteria, showing that psychosocial factors and physiology states influence the presentation of functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). As for the biopsychosocial aspects, complex factors such as environmental, psychological and biological factors interactively play an important role in the development and maintenance of FGIDs [9, 10].

Some meta-analyses investigated the relationship between IBS and mental disorders such as depression and anxiety previously [7, 11,12,13]. A pairwise meta-analysis including 10 studies evaluated the mood changes between healthy controls and IBS patients. It indicated that the depression and anxiety levels were higher in IBS patients than in healthy controls (SMD = 0.80; 95% CI 0.42–1.19 and SMD = 0.76; 95% CI 0.47–0.69 respectively) [7]. Similar results were revealed in another three studies about depression or anxiety on the symptoms or prevalence of IBS patients [11,12,13]. Although previous reviews found that patients with IBS had a higher risk of depression or anxiety compared with healthy controls under directly comparing, the difference of depression and anxiety among different IBS subtypes was still not well evaluated.

Understanding the comorbidity between IBS and mental disorders will be used to explore the complex pathophysiology of IBS, and further prevent trigger symptom flares so as to develop an individualized treatment plan among patients with different IBS subtypes. There was a need for a network meta-analysis ranking the level of depression and anxiety of different IBS subtypes. Therefore, this study aimed to: (1) compare the level of depression or anxiety among healthy controls and different IBS subtypes patients; (2) define which subtype of IBS is more likely associated with depression or anxiety; (3) Investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in different IBS subtypes patients.

Methods

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Statement [14]. This study was registered with PROSPERO, Number CRD42019124174.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library (the sixth edition, 2018) by two independent reviewers (H.Z.C. and L.M.X.) from their inception to June 2018, and the last search data was updated on Aug 17, 2020. The following key terms were used in the search strategies: (irritable bowel syndrome OR IBS) AND (depression OR depressive disorders OR dysthymic disorder OR anxiety OR anxiety disorders OR anxiousness OR mood disorders). The search strategies were well designed and varied from different databases. The details of search strategies were presented in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) studies that investigated anxiety and/or depression level in different IBS subtypes patients measured at baseline or the same time point without design restrictions; (2) studies that assessed anxiety and depression through validated psychometric measures such as Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) and others; (3) patients met established diagnostic criteria of IBS, including ROME I, II, III, IV.

The patients under the diagnoses of IBS due to the general medical condition, post‐infectious IBS or related serious comorbidities were excluded.

Selection of studies and data extraction

A pre-made form with characteristics (first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, age, gender, IBS diagnostic criteria, anxiety and depression scale, etc.) and target outcomes (anxiety level, depression level, depression prevalence, anxiety prevalence, etc.) were prepared. Two reviewers (H.Z.C. and L.M.X.) independently screened the abstracts and full-texts and extracted data. Rome IV criteria used the term “IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M)” instead of “IBS alternating type (IBS-A)”, so we combined the data of these two types. The third reviewer (Z.L.D.) was invited for rechecking data extraction, and any disagreements were discussed among three reviewers.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two authors (Y.L. and L.M.X.) independently assessed the quality of included cohort studies or case–control studies according to the criteria developed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) [15]. The NOS is widely used for cohort study and case–control study quality assessment focusing on the selection, comparability, exposure or outcome. For cross-sectional studies, the quality of cross-sectional study was assessed using criteria recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [16]. The criteria were divided into 11 items such as source of information, inclusion/exclusion criteria, time period for identity, subjects consecutive, evaluators masked, quality assurance assessments and so on. For each question, a score of 1 for “Yes” or 0 for “No”/ “Unclear” was given, out of a total score of 11. And studies achieving 6 or more points were considered to be of high quality. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion among the author group.

Statistical analyses

A frequentist model was used in this network meta-analysis to combine direct and indirect evidence from all included studies. Stata 13.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) was used to complete all analyses. First, standard pairwise meta-analysis was conducted with a random-effects model. Second, a network meta-analysis was processed using the mvmeta package of the Stata software, which was based on a multiple regression model. Evidence of inconsistency was checked using the node-splitting method. Random-effects pairwise and network meta-analyses were applied to obtain estimates for outcomes, and these estimates were presented as standardized mean differences (SMD) (continuous outcomes) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For all outcomes, network diagrams were used to summarize the evidence. The characteristics of included studies were summarized in a table and presented the comparisons in different tables. For outcomes, we also displayed the ranking probabilities of interventions by the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) which would show the best rank mostly approaching 1 [17]. For the included studies reporting the prevalence of depression and anxiety in different IBS subtypes patients, R 4.0.2 software was used to do a single arm Meta-analysis. This analysis took study effects into account, and the results were calculated by a binary random-effect method (Dersimonian-Laird). Forest plots were used to illustrate the prevalence with 95% CIs.

Results

Literature search

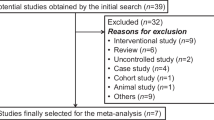

The literature search yielded 4810 reports, of which 252 were excluded for duplication, and 4533 were excluded on the basis of titles or abstracts that were irrelevant to the topic, and seven were excluded from the remaining 25 literatures after reading the full texts. Finally, 18 studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] with 7095 participants were included for analysis, of which four studies were cohort studies, eight studies were case–control studies, the remaining six studies were cross-sectional studies. The PRISMA flow chart of literature studies for meta-analysis was illustrated in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The baseline and general characteristics of the included studies were extracted and listed in Table 1. Eighteen studies were all published in English between 1998 and 2020, and the study samples ranged from 29 to 1987 participants. The level of depression and anxiety were compared in five groups (Healthy controls, IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M and IBS-U). Networks of eligible comparisons for the level of depression and anxiety were presented in Fig. 2. Twelve studies [18,19,20,21, 24, 26,27,28, 33, 34] used the HADS at baseline to measure the levels of anxiety and depression. IBS was diagnosed using the Rome III criteria in seven studies [18, 24,25,26, 29, 30, 34], Rome II criteria in nine studies [19,20,21,22, 27, 28, 31, 32, 35], one [33] used Rome IV criteria, one study [23] just mentioned they used Rome criteria. More details of included studies and the quality assessment results were showed in Table 1.

The level of depression and anxiety in different IBS subtypes

Depression

Thirteen [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, 30, 33] included studies reported depression level in patients with different IBS subtypes. Direct pairwise random-effects meta-analyses showed healthy controls had a lower level depression than IBS-M (SMD = − 1.63; 95% CI − 2.48, − 0.79; P < 0.05), IBS-C (SMD = − 1.67; 95% CI − 2.45, − 0.89; P < 0.05) and IBS-D (SMD = − 1.59; 95% CI − 2.18, − 0.99; P < 0.05), while no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy controls (SMD = − 0.07; 95% CI − 0.75, 0.60; P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference among different IBS subtypes, IBS-M vs IBS-C (SMD = 0.02; 95% CI − 032, 0.29; P > 0.05, I2 = 81.7%), IBS-M vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.17; 95% CI − 0.16, 0.49; P > 0.05), IBS-M vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.53; 95% CI − 0.18, 1.24; P > 0.05), IBS-C vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.13; 95% CI − 0.11, 0.37; P > 0.05), IBS-C vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.68; 95% CI − 0.08, 1.43; P > 0.05), IBS-D vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.65; 95% CI − 0.07, 1.36; P > 0.05). More details were showed on Table 2, Figs. 3 and 4.

The results of the network analysis also showed healthy controls had a lower level depression than IBS-M (SMD = − 1.57; 95% CI − 2.21, − 0.92; P < 0.05), IBS-C (SMD = − 1.53; 95% CI − 2.13, − 0.93; P < 0.05) and IBS-D (SMD = − 1.41; 95% CI − 1.97, − 0.85; P < 0.05), while no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy controls (SMD = − 0.58; 95% CI − 2.15, 1.00; P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference among different IBS subtypes, IBS-M vs IBS-C (SMD = 0.04; 95% CI − 0.55, 0.62; P > 0.05), IBS-M vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.16; 95% CI − 0.42, 0.74; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-M (SMD = − 0.99; 95% CI − 2.56, 0.59; P > 0.05), IBS-D vs IBS-C (SMD = − 0.12; 95% CI − 0.66, 0.42; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-C (SMD = − 0.95; 95% CI − 2.52, 0.62; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-D (SMD = − 0.83; 95% CI − 2.39, 0.73; P > 0.05). More details were showed on Table 3.

Anxiety

Twelve [18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27,28, 30, 33] studies provided the data of the anxiety level in patients with different IBS subtypes. Direct pairwise random-effects meta-analyses showed that healthy controls had a lower level anxiety than IBS-M (SMD = − 1.80; 95% CI − 2.70, − 0.90; P < 0.05), IBS-C (SMD = − 1.34; 95% CI − 2.02, − 0.65; P < 0.05), IBS-D (SMD = − 1.36; 95% CI − 1.95, − 0.78; P < 0.05) and IBS-U (SMD = − 0.70; 95% CI − 1.38, − 0.02; P < 0.05). There was also no significant difference among different IBS subtypes, IBS-M vs IBS-C (SMD = 0.02; 95% CI − 0.27, 0.30; P > 0.05), IBS-M vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.00; 95% CI − 0.11, 0.11; P > 0.05), IBS-M vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.35; 95% CI − 0.36, 1.05; P > 0.05), IBS-C vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.03; 95% CI − 0.18, 0.24; P > 0.05), IBS-C vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI − 0.40, 1.08; P > 0.05), IBS-D vs IBS-U (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI − 0.37, 1.05; P > 0.05). More details were showed on Table 2, Figs. 5 and 6.

The results of the network analysis also showed healthy controls had a lower level anxiety than IBS-M (SMD = − 1.43; 95% CI − 2.06, − 0.79; P < 0.05), IBS-C (SMD = − 136; 95% CI − 1.97, − 0.75); P < 0.05) and IBS-D (SMD = − 1.35; 95% CI − 1.92, − 0.78; P < 0.05), no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy controls (SMD = − 0.89; 95% CI − 2.42, 0.64; P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference among different IBS subtypes, IBS-M vs IBS-C (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI − 0.51, 0.65; P > 0.05), IBS-M vs IBS-D (SMD = 0.08; 95% CI − 0.49, 0.64; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-M (SMD = − 0.54; 95% CI − 2.07, 0.99; P > 0.05), IBS-D vs IBS-C (SMD = − 0.01; 95% CI − 0.55, 0.54; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-C (SMD = − 0.47; 95% CI − 1.99, 1.06; P > 0.05), IBS-U vs IBS-D (SMD = − 0.46; 95% CI − 1.98, 1.06; P > 0.05). More details were showed on Table 3.

Inconsistency analyses

Node-splitting analysis showed that there were no inconsistencies between direct and indirect comparisons (P > 0.05).

Rank probability

Table 4 showed, for each IBS subtypes, the likelihood with the highest levels of depression and anxiety. Rank probability indicated that IBS-M had the highest levels of depression, followed by IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-U, healthy controls (Fig. 7), and the levels of anxiety in different IBS subtypes and healthy controls showed the same probability with depression level (Fig. 8).

The prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBS patients

Nine studies [18, 21, 27, 29, 30,31,32, 34, 35] reported the prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBS patients. The details can be found in Table 5. Single-arm meta analysis showed the prevalence of depression and anxiety in total IBS was 36% and 44% respectively. Subgroup analyses showed the prevalence of depression in IBS-M, IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-U was 34%, 38%, 37% and 22% respectively (Fig. 9), and anxiety prevalence in IBS-M, IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-U was 37%, 40%, 37% and 11% respectively (Fig. 10).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study was the first network meta-analysis that explored the level and prevalence of depression or anxiety among healthy controls and different IBS subtypes patients. In this network meta analysis, 18 studies with a total of 7095 participants were included. Healthy controls had a lower level depression and anxiety than all IBS subtypes, but no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy controls in depression level. No significant difference was found in the level of depression and anxiety among different IBS subtypes. Ranking probability showed that IBS-M was associated with the highest level of depression and anxiety symptoms, followed by IBS-C/IBS-D and IBS-U. Single-arm meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety was highest in IBS-C (38 and 40% respectively) and lowest in IBS-U (22 and 11% respectively).

Psychological factors play an important role in the development and maintenance of IBS, and have high correlation with IBS patients’ symptom severity, treatment response, sick cycle. It has been investigated by previous studies that IBS patients were more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than healthy controls [7, 11,12,13]. But these studies did not distinguish the differences explicitly among different IBS subtypes in the comorbidities or level of depression and anxiety. This study investigated which subtypes of IBS were likely to be comorbid with depression and anxiety and provide useful information for health providers to make appropriate decisions. Based on direct and indirect comparing, no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy controls in depression level. The result was in conflict with the indirect comparison. We found that only one study [25] reported the data and the direct comparison pooled effect size was only − 0.7, indicating that even if there was a statistical difference, the difference was small and may be caused by statistical deviation. Therefore, it can be judged that there was no difference in anxiety level between healthy controls and IBS-U. We suggest that adequate psychological screening and appropriate psychotherapy are demanded for patients of IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M.

Another important finding of this study was the confirmation of no significant difference in the level of depression and anxiety among different IBS subtypes. But the ranking probability showed that the IBS-M was associated with the highest level of depression and anxiety. The result was inconsistent with the previous pairwise meta-analysis published in 2017 [10]. The meta-analysis indicated that the pooled SMDs of depression and anxiety levels were highest in IBS-C (0.83 and 0.81). We found that the samples used in the subgroup analysis in that meta-analysis were smaller than our study, it seemed that our results were more reliable. With respect to the prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBS patients, our single-arm meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of both depression and anxiety in total IBS patients was more than 20%, which was consistent with the study published in 2019[13]. What’s more, IBS-U was firstly included in this meta-analysis, the prevalence of anxiety among different IBS subtypes was also conducted.

There were some limitations in our systematic review. First, different study types were involved including cohort, case control and cross-sectional study. Second there were different versions of IBS diagnose criteria and mental disorders criteria. Third, different measurement scales were used in the included studies including HRSD, HRSA, MPPI, BDI, and HADS. In this study, 8 scores of HADS were defined as the cut-off point of mental disorders in three studies [18, 27, 34], 10 scores of HADS as the cut-off point in one study [21], 11 scores of HADS as the cut-off point in two study [29, 32]. It was considered that the cut-off of eight scores on the HADS showed the most optimal benefit between sensitivity and specificity [29]. Besides, the chronic illness is also a major risk factor for depression and increases the duration of depressive episode [31]. Symptom-screening questionnaire such as HADS may cause bias for overestimating or underestimating the psychological severity of medically ill patients [36], which leading to the misdiagnosis or over diagnosis of psychological disorders. So we suggest using different psychological scales and proper cut-off point to reflect the patients’ mental conditions.

Through this study, big heterogeneities were found among existed studies focused on the subtypes of IBS and mental disorders. We suggested high-quality community-based cross-sectional study surveying the level of depression and anxiety in patients with different subtypes of IBS should be carried out. Depression and anxiety assessments should be provided by clinical service, as there were a high prevalence and low diagnosis and treatment rate of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with IBS [37]. As depression or anxiety can show noteworthy phases changing even under effective treatments [38], we also recommend continuously monitoring the patient's psychological level to take control of the progress of the disease treatment.

Conclusion

Based on the available evidence, healthy controls had a lower level of depression and anxiety than all IBS subtypes, but no significant difference was found between IBS-U and healthy control in depression level. No significant difference was found in the level of depression and anxiety among different IBS subtypes. Ranking probability results showed that IBS-M was associated with higher depression and anxiety level. Adequate psychological screening and appropriate psychotherapy are more suitable and needed for patients of IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-M instead of IBS-U. Further studies on this topic should be carried out.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IBS:

-

irritable bowel syndrome

- SMD:

-

standardized mean difference

- IBS-D:

-

IBS with diarrhea

- IBS-C:

-

IBS with constipation

- IBS-M:

-

IBS with mixed symptoms of constipation and diarrhea

- IBS-U:

-

unsubtyped IBS

- FGIDs:

-

functional gastrointestinal disorders

- HADS:

-

the hospital anxiety and depression scale

- HRSD:

-

the Hamilton rating scale for depression

- HRSA:

-

the Hamilton rating scale for anxiety

- BDI:

-

the Beck's depression inventory

- SDS:

-

the self-rating depression scale

- NOS:

-

the Newcastle–Ottawa scale

- AHRQ:

-

the agency for healthcare research and quality

- SUCRA:

-

the surface under the cumulative ranking curve

References

Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949–58.

Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712–21.

Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1023–34.

Corsetti M, Whorwell P. The global impact of IBS: time to think about IBS-specific models of care? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:727–36.

Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10:299–309.

Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1393–407.

Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651–60.

Kabra N, Nadkarni A. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: A clinic based study from India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:77–80.

Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology. Clin Feat Rome IV Gastroenterol. 2016;150:1262–79.

Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, et al. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765–74.

Lee C, Doo E, Choi JM, et al. The increased level of depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:349–62.

Zhang Q-E, Wang F, et al. Depressive symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:1504–12.

Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Zamani V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:132–43.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2008. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 24 Dec 2020.

Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, et al. Celiac Disease (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No.104). Appendix D. Quality Assessment Forms. US: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/. Accessed 24 Dec 2020.

Georgia S, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:163–71.

Thijssen AY, Mujagic Z, Jonkers DM, et al. Alterations in serotonin metabolism in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;43:272–82.

Sugaya N, Shimada H. Relationship between cognitive factors and anxiety in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19:308–15.

Seminowicz DA, Labus JS, Bueller JA, et al. Regional gray matter density changes in brains of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:48–57.

Miller V, Carruthers HR, Morris J, et al. Hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome: an audit of one thousand adult patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:844–55.

Medeiros MT, De Goncalves, Oliveira RB, et al. The effects of sildenafil on rectal sensitivity and tone in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:577–86.

Lee CT, Chuang TY, Lu CL, et al. Abnormal vagal cholinergic function and psychological behaviors in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a hospital-based Oriental study. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1794–9.

Jones MP, Chey WD, Singh S, et al. A biomarker panel and psychological morbidity differentiates the irritable bowel syndrome from health and provides novel pathophysiological leads. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:426–37.

Jamali R, Jamali A, Poorrahnama M, et al. Evaluation of health related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Health Qual Life Out. 2012;10:12.

De-Rong X-J, Shu-Kun. Increased intestinal mucosal leptin levels in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:46–57.

Cho HS, Park JM, Lim CH, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver. 2011;5:29.

Camilleri M, Mckinzie S, Busciglio I, et al. Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychologic, and autonomic functions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:772–81.

Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, et al. Characteristics of functional bowel disorder patients: a cross-sectional survey using the Rome III criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:312–21.

Bruno A, Zoccali RA, Pandolfo G, et al. Negative Emotions in Irritable Bowel Sindrome: which differences among IBS Subtypes. Mediterr J Clin Psychol. 2018;6:2282–1619.

Mearin F, Badía X, Balboa A, et al. Predictive factors of irritable bowel syndrome improvement: 1-year prospective evaluation in 400 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;23:815–26.

Okami Y, Kato T, Nin G, et al. (2011) Lifestyle and psychological factors related to irritable bowel syndrome in nursing and medical school students. J Gastroenterol. 46: 1403–10.

Qin G, Zhang Y, Yao SK. Serotonin transporter and cholecystokinin in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: Associations with abdominal pain, visceral hypersensitivity and psychological performance. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1632–41.

Mujagic Z, Ludidi S, Keszthelyi D, et al. Small intestinal permeability is increased in diarrhoea predominant IBS, while alterations in gastroduodenal permeability in all IBS subtypes are largely attributable to confounders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:288–97.

Ladep NG, Obindo TJ, Audu MD, et al. Depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome in Jos. Nigeria World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7844–7.

Identifying and managing depression in the medical patient. Prim care companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:282–95.

Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Kansagara D. Nonpharmacologic versus pharmacologic treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:350–9.

Fu CW, Tan AW, Sheng F, et al. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms in patients with somatic disorders in urban China: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2007;37:185–99.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the supporting of the project "acupuncture for depressive symptoms in IBS patients: a single blinded, randomized controlled Study” (Ref. SCM/025/KY, Hong Kong Baptist University).

Funding

This study was supported by Faculty Research Grant, Hong Kong Baptist University (Ref. SCM/025/KY, Hong Kong Baptist University). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z.X. and Z.L.D. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. Y.K.H. provided methodological advice of the study. W.Y.S. and W.E.K. assisted in research preparation and involved in data analysis acquisition. H.Z.C. and L.M.X. were responsible for literature searching and data acquisition. Y.L. and L.M.X. assessed the quality of included studies. L.M.X. analysed and interpreted the data. H.Z.C. and L.M.X wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Z.L.D., Y.J.Y. and W.F.Y. gave critical advice to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethics approval and consent to participate were needed.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

All authors have no potential competing interests relevant to this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Search strategy

Appendix 1: Search strategy

PubMed via Ovid

#1 Irritable Bowel Syndrome [Mesh].

#2 irritable bowel syndrome [Title/Abstract].

#3 #1 OR #2.

#4 depression [Mesh].

#5 depressive disorder [Mesh].

#6 anxiety [Mesh].

#7 anxiety disorders[Mesh].

#8 depression[Title/Abstract].

#9 depressive disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#10 dysthymic disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#11 melancholia[Title/Abstract].

#12 despondency[Title/Abstract].

#13 dysthymic disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#14 dysthymia[Title/Abstract].

#15 melancholy[Title/Abstract].

#16 sadness[Title/Abstract].

#17 low mood[Title/Abstract].

#18 despair[Title/Abstract].

#19 anxiety[Title/Abstract].

#20 anxiety disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#21 anxiousness[Title/Abstract].

#22 angst[Title/Abstract].

#23 apprehension[Title/Abstract].

#24 fear[Title/Abstract].

#25 nervousness[Title/Abstract].

#26 dysphoria[Title/Abstract].

#27 mood disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#28 affective disorder*[Title/Abstract].

#29 #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28.

#30 #3 AND #29.

EMBASE via Ovid

#1 ‘Irritable Bowel Syndrome’/exp.

#2 ‘irritable bowel syndrome’: ti,ab,kw.

#3 #1 OR #2.

#4 ‘depression’ /exp.

#5 ‘depressive disorder’ /exp.

#6 ‘anxiety’ /exp.

#7 ‘anxiety disorders’ /exp.

#8 ‘depression’: ti,ab,kw.

#9 ‘depressive disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#10 ‘dysthymic disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#11 ‘melancholia’: ti,ab,kw.

#12 ‘despondency’: ti,ab,kw.

#13 ‘dysthymic disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#14 ‘dysthymia’: ti,ab,kw.

#15 ‘melancholy’: ti,ab,kw.

#16 ‘sadness’: ti,ab,kw.

#17 ‘low mood’: ti,ab,kw.

#18 ‘despair’: ti,ab,kw.

#19 ‘anxiety’: ti,ab,kw.

#20 ‘anxiety disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#21 ‘anxiousness’: ti,ab,kw.

#22 ‘angst’: ti,ab,kw.

#23 ‘apprehension’: ti,ab,kw.

#24 ‘fear’: ti,ab,kw.

#25 ‘nervousness’: ti,ab,kw.

#26 ‘dysphoria’: ti,ab,kw.

#27 ‘mood disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#28 ‘affective disorder*’: ti,ab,kw.

#29 #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26. OR #27 OR #28.

#30 #3 AND #29.

Cochrane library

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Irritable Bowel Syndrome].

#2 irritable bowel syndrome: ti,ab,kw.

#3 #1 OR #2.

#4 MeSH descriptor: [depression].

#5 MeSH descriptor: [depressive disorder].

#6 MeSH descriptor: [anxiety].

#7 MeSH descriptor: [anxiety disorders].

#8 depression: ti,ab,kw.

#9 depressive disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#10 dysthymic disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#11 melancholia: ti,ab,kw.

#12 despondency: ti,ab,kw.

#13 dysthymic disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#14 dysthymia: ti,ab,kw.

#15 melancholy: ti,ab,kw.

#16 sadness: ti,ab,kw.

#17 low mood: ti,ab,kw.

#18 despair: ti,ab,kw.

#19 anxiety: ti,ab,kw.

#20 anxiety disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#21 anxiousness: ti,ab,kw.

#22 angst: ti,ab,kw.

#23 apprehension: ti,ab,kw.

#24 fear: ti,ab,kw.

#25 nervousness: ti,ab,kw.

#26 dysphoria: ti,ab,kw.

#27 mood disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#28 affective disorder*: ti,ab,kw.

#29 #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26. OR #27 OR #28.

#30 #3 AND #29.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Z., Li, M., Yao, L. et al. The level and prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome: a network meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 21, 23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01593-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01593-5