Abstract

Background

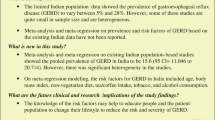

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which leads to acid reflux into the esophagus, is a common gastrointestinal disorder. Several studies have shown the prevalence of GERD in Iranian population, but their evidence is contradictory. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the epidemiology of GERD in Iran.

Methods

The entire steps of this systematic review and meta-analysis were based on the MOOSE protocol, and the results were reported accordance with the PRISMA guideline. This review is registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42020142861). To find potentially relevant published articles, comprehensive search was done on international online databases Scopus, Science Direct, EMBASE, PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, EBSCO, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Iranian online databases and the Google Scholar search engine in June 2019. Cochran test and I2 index were used to assess the heterogeneity of the studies. Data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software ver. 2. The significance level of the test was considered to be P < 0.05.

Results

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian population was 5.64% (95%CI [confidence interval]: 3.77–8.35%; N = 66,398), 12.50% (95%CI: 9.63–16.08%; N = 110,388), 18.62% (95%CI: 12.90–26.12%; N = 70,749) and 43.07% (95%CI: 35.00–51.53%; N = 73,189), respectively. The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn in Iranian population was 2.46% (95%CI: 0.93–6.39%; N = 18,774), 9.52% (95%CI: 6.16–14.41%; N = 54,125), 8.19% (95%CI: 2.42–24.30%; N = 19,363) and 23.20% (95%CI: 13.56–36.79%; N = 26,543), respectively. The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian population was 4.00% (95%CI: 1.88–8.32%; N = 18,774), 9.79% (95%CI: 5.99–15.60%; N = 41,140), 13.76% (95%CI: 6.18–44.31%; N = 19,363) and 36.53% (95%CI: 19.30–58.08%; N = 21,174), respectively. The sensitivity analysis for prevalence of all types GERD, heartburn and regurgitation symptoms by removing a study showed that the overall estimate is still robust.

Conclusion

The present meta-analysis provides comprehensive and useful information on the epidemiology of GERD in Iran for policy-makers and health care providers. This study showed a high prevalence of GERD in Iran. Therefore, effective measures on GERD-related factors such as lifestyle can be among the health policies of Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which leads to acid reflux into the esophagus, is a common gastrointestinal disorder and results in typical painful symptoms such as heartburn and/or regurgitation [1]. However, it may also appear with atypical symptoms including cough, asthma, chest pain, and fatigue [2].

Permanent acid reflux may cause more severe complications, including erosive esophagitis, esophageal strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, hiatus hernia, delayed gastric emptying, and visceral hypersensitivity [1, 3,4,5].

Several risk factors are associated with GERD, including Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), type of food, beverages, smoking, family history, high body mass index (BMI), physical activity, salt, or consuming pickles with meals and fast food, which are more associated with the lifestyle of the patient [5,6,7]. It has also been shown that age, gender, pregnancy, and geographical variation are also related to GERD [7]. In addition, it has been suggested that vertebral fractures and/or spinal malalignment may affect the incidence of GERD [8, 9]. In Iranian studies, consumption of NASIDs and pickle consumption, and smoking is more harmful factors [10, 11].

A systematic review of longitudinal studies suggests that the incidence of GERD has increased in recent decades. If this trend continues, it may rapidly increase the serious complications of GERD, affect the patient’s quality of life, and increase the cost of health care systems [12, 13].

Increasing the GERD awareness to improve Iranian people’s health may be necessary. There is much information in Western cultures that can be generalized to an Iranian person but cannot match completely. Therefore, understanding the epidemiological effects of GERD in Iranian society can help healthcare professionals and policymakers take the next steps in creating the list of priorities for disease management.

Several studies have shown the prevalence of GERD in Iranian population, but their evidence is contradictory [10, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Therefore, a structured review of all the documentation and their combination can provide a more complete picture of the dimensions of this disease in Iranian society. One of the main goals of meta-analysis, which is a combination of different studies, is to reduce the difference between parameters due to the increased number of studies involved in the analysis process. Another important goal of meta-analysis is to address inconsistencies in the results and their causes [40,41,42]. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the epidemiology of GERD in Iran.

Methods

Study protocol

The entire steps of this systematic review and meta-analysis were based on the Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) protocol [42], and the results were reported accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline [43]. Two authors independently preformed all study steps. In the case of dispute, a third author was involved. We registered this review at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42020142861), Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020142861.

Search strategy

To find potentially relevant published articles, comprehensive search was done on international online databases Scopus, Science Direct, EMBASE, PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, EBSCO, Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews - CDSR), Web of Science and national online databases Iranian Research Institute for Information Science and Technology (IranDoc) (https://irandoc.ac.ir), Scientific Information Database (SID) (http://www.sid.ir/), Magiran (http://www.magiran.com/), Regional Information Center for Science and Technology (RICST) (http://en.ricest.ac.ir/), Iranian National Library (http://www.nlai.ir/), and Barakat Knowledge Network System (http://health.barakatkns.com) and the Google Scholar search engine in June 2019. Our search was done to retrieve all literature related to GERD in Iran. The reference list of articles was reviewed to find the gray literature. The studies identified by our search strategies were entered into Endnote X7 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA) software.

The related articles were searched in PubMed using a combination of expressions and terms Medical Subject Heading (MeSH): “gastroesophageal reflux”[MeSH Terms] OR “gastroesophageal reflux disease” [Text Word] OR “heartburn”[MeSH Terms] AND “Iran”[MeSH Terms]. Search terms were combined using Boolean operators of “OR” or “AND”.

Study selection

The two researchers independently reviewed the articles on the abovementioned databases. The third researcher examined the consistency between the data extracted by the two researchers, and the contradictory results were discussed and resolved. After collecting literature from the databases, the next step was to assess whether the articles corresponded to the content of the title and abstract. The second and third stages were the review of the remaining articles with full text.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included the studies that were: (1) written in English or Persian; (2) cross-sectional studies; (3) with the primary aim of reporting the prevalence of GERD, heartburn and regurgitation; and (4) preformed among adults.

We excluded studies that: (1) had non-random sample size; (2) were non-relevant; (3) GERD diagnosis was not defined by heartburn and regurgitation; (4) were non-Iranian; (5) were case reports, review articles, congresses, letters to the editor without quantitative data, and theses.

Data extraction and management

In case of duplicate publication, we contacted the researchers to clarify the original publication, and if we did not get an answer, we chose the study with the largest number of participants for cases with overlapping data, if necessary, additional details were extracted from the secondary articles.

We extracted the following data from each study: First author, year of publication, year of study, place of study, study design, method of diagnosis, data collection, characteristics of participants and estimation of prevalence.

Qualitative assessment

The modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of studies [44]. The studies were divided into three categories based on the scores: high risk studies (scores ranging from 1 to 4), moderate risk (scores ranging from 5 to 7), and low risk (scores ranging from 8 to 10). Low and medium risk studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of the GERD is shown using the event rate. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software ver 2 using sample size (N) and standard error (SE). To determine women to men ratio, we calculated the odds ratio (OR). Cochran Q test and I2 index were used to assess the heterogeneity of the studies. There are three categories for I2 index: I2 index below 25% is low heterogeneity, 25–75% is medium, and above 75% is high heterogeneity [45, 46]. For cases with low heterogeneity, the fixed effects model was used and for cases with medium and high heterogeneity, the random effects model was used. Subgroup analysis was used to find the cause of heterogeneity in the studies. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing a study at a time to assess the predictive power. Mixed-effects meta-regression was used to investigate the relationship between continuous variables such as the time of study and the prevalence [47]. Finally, distribution bias was evaluated using funnel plot, and Egger and Begg’s tests. Statistical analysis and graph diagrams were performed using CMA version 2. The significance level of the test was considered to be P < 0.05.

Results

Search results and characteristics

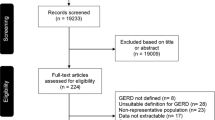

Our initial search found 4260 records. After removing 2130 duplicates, 2130 unique documents were reviewed for relating the titles and abstract. Then, we reviewed the full text of 101 articles. Finally, 30 articles (23 studies for GERD, 20 studies for heartburn, and 13 studies for regurgitation) were included in the study (Fig. 1). The mean age of the participants (in 14 reported studies) was 39.35 years (95% CI: 34.98–43.71). Table 1 shows the characteristics of each study.

GERD prevalence and sensitivity analysis

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian population was 5.64% (95% CI: 3.77–8.35%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.76%, P < 0.001; N = 66,398), 12.50% (95% CI: 9.63–16.08%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.50%, P < 0.001; N = 110,388), 18.62% (95% CI: 12.90–26.12%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.66%, P < 0.001; N = 70,749) and 43.07% (95% CI: 35.00–51.53%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.66%, P < 0.001; N = 73,189), respectively (Fig. 2).

The sensitivity analysis for prevalence of all types GERD symptoms by removing a study showed that the overall estimate is still robust (Figure 1- supplementary).

Subgroup analysis of GERD

The subgroup analysis for the daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD symptoms is shown in Table 2. For the daily prevalence of GERD, the subgroup analysis of the study population (P < 0.001) and the data collection method (P = 0.019) were significant. For the weekly prevalence of GERD, subgroup analysis of the area (P = 0.001) and study population (P < 0.001) were significant. For the monthly prevalence of GERD, the subgroup analysis of the study population was significant (P = 0.001). For the overall prevalence of GERD, the subgroup analysis of the area (P < 0.001), the study population (P < 0.001) and the quality of studies (P = 0.005) were significant. Other variables were not significant.

The prevalence of GERD by gender

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian males was 5.72% (95% CI: 3.41–9.46%; heterogeneity: I2 = 97.44%, P < 0.001; N = 26,004), 11.38% (95% CI: 8.10–15.75%; heterogeneity: I2 = 97.80%, P < 0.001; N = 19,453), 15.68% (95% CI: 10.67–22.45%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.15%, P < 0.001; N = 8865) and 39.26% (95% CI: 32.35–46.62%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.04%, P < 0.001; N = 31,704) (Figure 2-supplementary).

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian females was 7.88% (95% CI: 3.67–16.11%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.56%, P < 0.001; N = 31,588), 12.81% (95% CI: 9.47–17.10%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.04%, P < 0.001; N = 19,380), 16.96% (95% CI: 13.17–21.56%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.17%, P < 0.001; N = 21,567), and 45.51% (95% CI: 38.22–52.99%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.99%, P < 0.001; N = 38,252) (Figure 3-supplementary).

Odds ratio (OR) for the prevalence of daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD in women compared to men in Table 2 shows that there is a significant difference only in the daily prevalence of GERD (P = 0.003).

Meta-regression and publication bias for prevalence of GERD

The meta-regression model based on years of study for GERD prevalence revealed that the meta-regression coefficient for daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD was (− 0.022, 95% CI: − 0.132 to 0.087, P= 0.688), (0.025, 95% CI: − 0.410 to 0.092, P= 0.450), (0.0140, 95% CI: − 0.057 to 0.085, P = 0.700) and (0.038, 95% CI: − 0.081 to 0.085, P= 0.104), respectively (Fig. 3).

Regarding publication bias, the significance level of Egger and Begg’s tests was (Egger = 0.024 and Begg’s = 0.152), (Egger = 0.628 and Begg’s = 0.624), (Egger< 0.001 and Begg’s = 0.533) and (Egger = 0.002 and Begg’s = 0.754) for the daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD, respectively (Figure 4-supplementary).

Heartburn prevalence and sensitivity analysis

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn in Iranian population was 2.46% (95% CI: 0.93–6.39%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.15%, P < 0.001; N = 18,774), 9.52% (95% CI: 6.16–14.41%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.58%, P < 0.001; N = 54,125), 8.19% (95% CI: 2.42–24.30%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.76%, P < 0.001; N = 19,363) and 23.20% (95% CI: 13.56–36.79%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.77%, P < 0.001; N = 26,543), respectively (Fig. 4).

The sensitivity analysis for prevalence of all types heartburn symptoms by removing a study showed that the overall estimate is still robust (Figure 5-Supplement).

Subgroup analysis of heartburn

For the daily prevalence of heartburn, the subgroup analysis of the area (P < 0.001), study population (P < 0.001), the quality of studies (P < 0.001) and method of data collection (P = 0.007) were significant (Table 3). For the weekly prevalence of heartburn, subgroup analysis of the area (P = 0.001), study population (P < 0.001) and year of study (P = 0.021) were significant (Table 3). For the monthly prevalence of heartburn, the subgroup analysis of the area (P < 0.001) and population (P = 0.044) was significant (Table 3). For the overall prevalence of heartburn, the subgroup analysis of the area (P = 0.019), and the study population (P < 0.001) were significant (Table 3). Other variables were not significant.

The prevalence of heartburn by gender

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn in Iranian males was 2.61% (95% CI: 0.59–10.75%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.19%, P < 0.001; N = 4778), 5.68% (95% CI: 1.81–16.44%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.69%, P < 0.001; N = 7257), 5.93% (95% CI: 3.93–8.84%; heterogeneity: I2 = 89.65%, P < 0.001; N = 4788) and 16.54% (95% CI: 10.9–24.28%; heterogeneity: I2 = 96.43%, P < 0.001; N = 1788) (Figure 6-supplementary).

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn in Iranian females was 2.90% (95% CI: 0.36–19.95%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.45%, P < 0.001; N = 2803), 6.89% (95% CI: 2.96–15.21%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.02%, P < 0.001; N = 5171), 9.90% (95% CI: 6.45–14.90%; heterogeneity: I2 = 92.19%, P < 0.001; N = 3183), 19.71% (95% CI: 11.89–30.89%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.02%, P < 0.001; N = 2803) (Figure 7-supplementary).

OR for the prevalence of daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn in women compared to men in Table 3 shows that there is a significant difference in the weekly (P = 0.015), monthly (P < 0.001) and overall (P = 0.008) prevalence of heartburn.

Meta-regression and publication bias for prevalence of heartburn

The meta-regression model based on years of study for heartburn prevalence revealed that the meta-regression coefficient for daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn was (0.136, 95% CI: − 0.241 to 0.514, P= 0.478), (0.109, 95% CI: 0.013 to 0.205, P= 0.025), (0.205, 95% CI: 0.004 to 0.405, P = 0.044) and (0.047, 95% CI: − 0.103 to 0.198, P= 0.539), respectively (Fig. 5).

Regarding publication bias, the significance level of Egger and Begg’s tests was (Egger = 0.028 and Begg’s = 0.707), (Egger = 0.118 and Begg’s = 0.392), (Egger = 0.005 and Begg’s = 0.548) and (Egger = 0.025 and Begg’s = 0.754) for the daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn, respectively (Figure 8-supplementary).

Regurgitation prevalence and sensitivity analysis

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian population was 4.00% (95% CI: 1.88–8.32%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.03%, P < 0.001; N = 18,774), 9.79% (95% CI: 5.99–15.60%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.55%, P < 0.001; N = 41,140), 13.76% (95% CI: 6.18–27.88%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.73%, P < 0.001; N = 19,363) and 36.53% (95% CI: 19.30–58.08%; heterogeneity: I2 = 99.86%, P < 0.001; N = 21,174), respectively (Fig. 6).

The sensitivity analysis for prevalence of all types regurgitation symptoms by removing a study showed that the overall estimate is still robust (Figure 9-Supplement).

Subgroup analysis of regurgitation

For the daily prevalence of regurgitation, the subgroup analysis of the area (P < 0.001), study population (P < 0.001), the quality of studies (P < 0.001) and the data collection method (P = 0.001) were significant (Table 4). For the weekly prevalence of regurgitation, subgroup analysis of the study population (P = 0.001) was significant (Table 4). For the monthly regurgitation of heartburn, the subgroup analysis of the population was significant (P < 0.001) (Table 4). For the overall prevalence of regurgitation, the subgroup analysis of the area (P < 0.001) was significant (Table 4). Other variables were not significant.

The prevalence of regurgitation by gender

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian males was 3.59% (95% CI: 1.17–10.47%; heterogeneity: I2 = 97.58%, P < 0.001; N = 4788), 7.93% (95% CI: 4.55–13.46%; heterogeneity: I2 = 95.25%, P < 0.001; N = 5008), 10.15% (95% CI: 5.61–17.70%; heterogeneity: I2 = 97.28%, P < 0.001; N = 4788) and 28.00% (95% CI: 24.66–31.60%; heterogeneity: I2 = 81.76%, P < 0.001; N = 4788) (Figure 10-supplementary).

The daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian females was 4.63% (95% CI: 0.78–23.11%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.76%, P < 0.001; N = 2803), 6.81% (95% CI: 3.64–12.41%; heterogeneity: I2 = 94.86%, P < 0.001; N = 3183), 5.23% (95% CI: 1.11–21.34%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.49%, P < 0.001; N = 2803) and 30.59% (95% CI: 17.89–47.14%; heterogeneity: I2 = 98.29%, P < 0.001; N = 2803) (Figure 11-supplementary).

OR for the prevalence of daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation in women compared to men in Table 4 shows that there is no significant difference in the prevalence of regurgitation.

Meta-regression and publication bias for prevalence of regurgitation

The meta-regression model based on years of study for regurgitation prevalence revealed that the meta-regression coefficient for daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of regurgitation was (0.091, 95% CI: − 0.206 to 0.390, P= 0.546), (0.081, 95% CI: − 0.029 to 0.192, P= 0.149), (0.162, 95% CI: 0.027 to 0.297, P = 0.018) and (0.002, 95% CI: − 0.001 to 0.002, P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 7).

Regarding publication bias, the significance level of Egger and Begg’s tests was (Egger = 0.060 and Begg’s = 0.452), (Egger = 0.221 and Begg’s = 0.999), (Egger = 0.011 and Begg’s = 0.999) and (Egger = 0.074 and Begg’s = 0.763) for the daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of heartburn, respectively (Figure 12-supplementary).

Discussion

The present study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of GERD in Iran. In this study, the prevalence of daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD in Iranian population was 5.64%, 12.50%, 18.62%, and 43.07%, respectively. In a systematic review in 2014, the weekly prevalence of GERD in North America was 18.1–27.8%, in South America was 23.0%, in Europe was 8.8–25.9%, in East Asia was 2.5–7.8%, in Middle East was 8.7–33.1% and in Australia was 11.6%, and was specifically reported for Iran to be 10.1–15.0% [49], which is consistent with the present study.

In the present study, the causes of heterogeneity in the studies can be attributed to the geographic region and the studied population, while previous studies also mentioned racial and geographical factors for the pathogenesis of GERD [49, 50].

In a systematic review in Iran, the causes of heterogeneity for the prevalence of GERD have been attributed to different criteria such as definition, difference in social factors, cultural background, and lifestyle in different cities or different populations [51]. On the other hand, due to the limitations of population-based studies, where precise diagnostic methods such as PH metric testing cannot be used, some of these differences can be due to the lack of a comprehensive standard for classifying symptoms and complications of GERD, which makes comparison between studies difficult [52]. Some differences in reported reflux rates may be due to cultural and ethnic differences in perceiving, expressing, and understanding symptoms of reflux. For example, there are differences in describing symptoms and diseases in some areas and among some ethnic groups, while other groups do not pay attention to the symptoms of the disease. It has been pointed out that different groups and cultures have different perceptions of the word “heartburn”. In a study in Boston among different ethnic groups, only 13% of Chinese and Korean people had a proper understanding of the word “heartburn” [53].

Iranian people are gaining weight such that the prevalence of obesity in Iranian adults is 21.5% [54]. Meanwhile, the economic and social status of people has changed rapidly. Therefore, some studies have reported that the above factors are important risk factors [55].

Smoking has always been associated with GERD. The relationship between smoking and GERD (any symptoms) continues even after smoking is stopped [39]. Smoking increases the frequency of GERD by reducing the pressure of the sphincter [56] and decreases the secretion of the bicarbonate of the saliva [57]. However, some other mechanisms may also be involved in the relationship between smoking and symptoms of GERD. Therefore, smoking may result in exaggerated negative intrathoracic pressure and inspiratory thoraco-abdominal pressure gradient, which may cause gastrointestinal reflux [58, 59]. In a meta-analysis, the prevalence of smoking among Iranian men and women was reported to be 21.7% and 3.6%, respectively [59].

There is varied evidence regarding the relationship between gender and GERD symptoms, but most studies show no relationship [60]. However, in many studies based on endoscopy, non-erosive and erosive GERD are more common in men and women, respectively [61, 62]. In the present study, only the daily symptoms of GERD were significantly higher in women compared to men.

The prevalence of GERD-related symptoms and tissue damage is different in ethnic/racial groups [63, 64]. We found a significant difference between the weekly and overall prevalence of GERD in different areas; the weekly and overall prevalence of GERD in the south was 21.26% and in the north was 60.86%. Iran has different ethnicities (Kurds, Persians, Turks, Arabs, Turkmen, etc.) with different customs and lifestyles, each of which predominantly lives in certain geographic area (e.g., Kurds are concentrated in western Iran) [65]. Nevertheless, the environmental or genetic factors that affect these differences are not clear yet [39].

The study with highest quality in this meta-analysis was the study of Islami et al. [39] on 49,975 people of the general population, with a daily, weekly, monthly, and overall GERD prevalence of 11.83%, 8.06%, 40.96%, and 60.86%, respectively, who reported a high incidence.

In the present study, the prevalence of daily, weekly, monthly, and overall prevalence of GERD did not change significantly over time. In 2005, a systematic review on population-based studies reported the weekly prevalence of GERD to be 10–20% in Europe and the United States and less than 5% in East Asia [66]. However, in a more recent systematic review in 2011, the weekly prevalence of GERD was reported to be 8.8–25.9% in Europe and 18.1–27.8% in North America and 2.5–7.8% in East Asia 49). Therefore, the global prevalence of GERD is increasing over time [49].

The results of the Egger’s test show that bias has been suggested for the overall prevalence of GERD. Publication bias is usually suggested for studies that are based on relationship assessment scale because studies with a positive result are more likely [48, 67].

There were several limitations for this early study, so interpreting the results should be done with cautious. The questionnaire consisted of only the major and common symptoms of GERD such as heartburn and acid reflux, but not other symptoms. Non-gastric manifestations of GERD are not included. Indeed, in the absence of a golden standard for the diagnosis of GERD, we only have the questionnaires, which are common in clinical or epidemiological studies.

Conclusion

The present meta-analysis provides comprehensive and useful information on the epidemiology of GERD in Iran for policy-makers and health care providers. This study showed a high prevalence of GERD in Iran. Therefore, effective measures on GERD-related factors such as lifestyle can be among the health policies of Iran.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this research are contained in the article.

Abbreviations

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- IranDoc:

-

Iranian Research Institute for Information Science and Technology

- SID:

-

Scientific Information Database

- RICST:

-

Regional Information Center for Science and TechnologyMOOSE Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- PRISMA:

-

Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis

- NOS:

-

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMA:

-

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis

References

Vakil N, Van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterology. 2006;101(8):1900.

Manterola C, Muñoz S, Grande L, Bustos L. Initial validation of a questionnaire for detecting gastroesophageal reflux disease in epidemiological settings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(10):1041–5.

El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(7):1692–9.

Mikami DJ, Murayama KM. Physiology and pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Clin. 2015;95(3):515–25.

Buckles DC, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW, McMillin C. Delayed gastric emptying in gastroesophageal reflux disease: reassessment with new methods and symptomatic correlations. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327(1):1–4.

Wong W, Lam K, Lai K, Hui W, Hu W, Lam C, et al. A validated symptoms questionnaire (Chinese GERDQ) for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in the Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(11):1407–13.

Kim O, Jang HJ, Kim S, Lee HY, Cho E, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and its related factors among women of reproductive age: Korea Nurses' Health Study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1133.

Ohba T, Ebata S, Koyama K, Haro H. Prevalence and key radiographic spinal malalignment parameters that influence the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients treated surgically for adult spinal deformity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18(1):8.

Kusano M, Hashizume K, Ehara Y, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Mori M. Size of hiatus hernia correlates with severity of kyphosis, not with obesity, in elderly Japanese women. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(4):345–50.

Mostaghni A, Mehrabani D, Khademolhosseini F, Masoumi SJ, Moradi F, Zare N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Qashqai migrating nomads, southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2009;15(8):961.

Vossoughinia H, Salari M, Amirmajdi EM, Saadatnia H, Abedini S, Shariati A, et al. An epidemiological study of gastroesophageal reflux disease and related risk factors in urban population of mashhad, iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(12);e15832.

El–Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):17–26.

Lee S-W, Lee T-Y, Lien H-C, Peng Y-C, Yeh H-J, Chang C-S. Correlation between symptom severity and health-related life quality of a population with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Res. 2017;10(2):78.

Nouraie M, Razjouyan H, Assady M, Malekzadeh R, Nasseri-Moghaddam S. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in Tehran, Iran: a population-based telephone survey. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10(3):289–94.

Nouraie M, Radmard AR, Zaer-Rezaii H, Razjouyan H, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Malekzadeh R. Hygiene could affect GERD prevalence independently: a population-based study in Tehran. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1353.

Hatami K, Pourshams A, Azimi K, Sarrafi M, Mehrabani M, Mostajabi P, et al. Dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome among blood donors. Govaresh. 2003;8(4):138–46.

Rogha M, Mohabatian B, Daemi P, Bashardoost N, Pourshams A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Esfahan. Govaresh. 2006;11(3):145–9.

Mahmoudi S, Pourshams A, Akbari M, Malekzadeh R. The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and gastroesophageal reflux disease among Tehran University students. Govaresh. 2012;8(4):159–62.

Somi MH, Farhang S, Mirinezhad K, Jazayeri E, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Moayeri S, et al. Prevalence and precipitating factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in a young population of Tabriz, northwest of Iran. Saudi medical journal. 2006;27(12):1878.

Pourshams A, Rahmani A, Hatami K. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Iran. Govaresh. 2005;10(1):48–53.

Bordbar G, Bolandnazar N-S. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): prevalence and association with psychological disorders among medical sciences students. Int J PharmTech Res. 2015;8(7):120–30.

Pourhoseingholi A, Safaee A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Boghimi-Dehkordi B, Habibi M, Vahedi M, et al. Prevalence and demographic risk factors of gastrointestinal symptoms in Tehran province. Ital J Public Health. 2010;7(1).

Khoshbaten M. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease in northwestern Tabriz, Iran. Ind J Gastroenterol. 2003;22(4):138–9.

Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi M. Heartburn and related factors in general population in Tehran, capital of Iran. East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7(2).

Honarkar Z, Baladast M, Khorram Z, Akhondi Sh AM, Masoodi M. An analysis of gastrointestinal symptoms in causalities of catastrophic earthquake of bam, Iran. Shiraz E-Med J. 2005;6(1):2.

Keshteli AH, Daneshpajouhnejad P, Adibi P. Risk factors of bloating and its association with common gastrointestinal disorders in a sample of Iranian adults. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(3):179–90.

Shahravan S, Maleki I. Prevalence and clinical conditions of gastroesophageal reflux: a population based study in sari city, Iran. Govaresh. 2013;18(2):112–3.

Reshadat R, Fattahi N, Iri R, Saeedi B, Shahabbaspoor Z, Emami L, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux and its related factors in Sanandaj. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2017;22(4).

Pourhoseingholi A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Barzegar F, Safaee A, Vahedi M, et al. Epidemiological features of gastro-esophageal reflux disease in Iran based on general population. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5(1):54.

Khodamoradi Z, Gandomkar A, Poustchi H, Salehi A, Imanieh MH, Etemadi A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Gastroesophageal reflux disease in southern Iran: pars cohort study. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2017;9(3):129.

Saberi-Firoozi M, Khademolhosseini F, Yousefi M, Mehrabani D, Zare N, Heydari ST. Risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in shiraz, southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2007;13(41):5486.

Aletaha N, Pourshams A, Nouraie M, Malekshah AF, Malekzadeh R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Gonbad city: the prevalence and risk factors. J Med Council Islamic Republic Iran. 2010;28(2):176–234.

Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Mofid A, GHOTBI MH, Razjouyan H, Nouraie M, RAMARD AR, et al. Epidemiological study of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: reflux in spouse as a risk factor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(1):144–53.

Solhpour A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Soltani F, Zarghi A, Habibi M, Ghafarnejad F, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms and body mass index: no relation among the Iranian population. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27(4):153–5.

Saberi HR, Moravveji AR. Gastrointestinal complaints in shift-working and day-working nurses in Iran. J Circadian Rhythms. 2010;8(1):9.

Hoseini-assal SK, Amra B. Respiratory symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux in adult population of more than 20 years old in Shahrekord. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2004;6(1):58–62.

Vakhshoori M, Keshteli AH, Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. Relationship between meal frequency and Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in Iranian adults. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(11):2998–3008.

Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F, Atshani SM, Chagharvand S, Souti F. The epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a survey on the prevalence and the associated factors in a random sample of the general population in the northern part of Iran. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013;4(3):175.

Islami F, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Semnani S, Kamangar F, et al. Determinants of gastroesophageal reflux disease, including hookah smoking and opium use–a cross-sectional analysis of 50,000 individuals. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89256.

Karimian M, Salamati M, Azami M. The relationship between metabolic syndrome and increased risk of Barrett's esophagus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):138.

Sayehmiri K, Tavan H. Systematic review and meta-analysis methods prevalence of peptic ulcer in IRAN. J Govaresh. 2015;20(4):250–8.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011.

Green S, Higgins J, Alderson P, Clarke M, Mulrow C, Oxman A. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. West Sussex: Wiley; 2008.

Ades A, Lu G, Higgins J. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Mak. 2005;25(6):646–54.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Ehsani MJ, Maleki I, Mohammadzadeh F, Mashayekh A. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Tehran, Iran. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(9):1419–22.

El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63(6):871–80.

Sharma P, Wani S, Romero Y, Johnson D, Hamilton F. Racial and geographic issues in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(11):2669.

Fazel M, Keshteli AH, Jahangiri P, Daneshpajouhnejad P, Adibi P. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Iran: SEPAHAN systematic review No. 2. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(Suppl 1):S10.

Delavari A, Moradi G, Birjandi F, Elahi E, Saberifiroozi M. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the Islamic Republic of Iran: a systematic review. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2012;4(1):5.

Spechler S, Jain S, Tendler D, Parker R. Racial differences in the frequency of symptoms and complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(10):1795–800.

Mirzazadeh A, Sadeghirad B, Haghdoost A, Bahreini F, Kermani MR. The prevalence of obesity in Iran in recent decade; a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38(3):1–11.

Rosaida MS, Goh K-L. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, reflux oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a multiracial Asian population: a prospective, endoscopy based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16(5):495–501.

Thomas GA, Rhodes J, Ingram JR. Mechanisms of disease: nicotine—a review of its actions in the context of gastrointestinal disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2(11):536.

Trudgill N, Smith L, Kershaw J, Riley S. Impact of smoking cessation on salivary function in healthy volunteers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(6):568–71.

Ayazi S, DeMeester SR, Hsieh C-C, Zehetner J, Sharma G, Grant KS, et al. Thoraco-abdominal pressure gradients during the phases of respiration contribute to gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(6):1718–22.

Moosazadeh M, Ziaaddini H, Mirzazadeh A, Ashrafi-Asgarabad A, Haghdoost AA. Meta-analysis of smoking prevalence in Iran. Addict Health. 2013;5(3–4):140.

Nusrat S, Nusrat S, Bielefeldt K. Reflux and sex: what drives testing, what drives treatment? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(3):233–47.

Cook M, Wild C, Forman D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the sex ratio for Barrett's esophagus, erosive reflux disease, and nonerosive reflux disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(11):1050–61.

Cho JH, Kim HM, Ko GJ, Woo ML, Moon CM, Kim YJ, et al. Old age and male sex are associated with increased risk of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis: analysis of data from local health examinations by the Korean National Health Insurance Corporation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(6):1034–8.

Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W. Abdominal obesity, ethnicity and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms. Gut. 2007;56(6):756–62.

Wang A, Mattek NC, Holub JL, Lieberman DA, Eisen GM. Prevalence of complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus among racial groups in a multi-center consortium. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(5):964–71.

Azami M, Moslemirad M, YektaKooshali MH, Rahmati S, Soleymani A, Shamloo MBB, et al. Workplace violence against Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Violence Vict. 2018;33(6):1148–75.

Dent J, El-Serag H, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54(5):710–7.

Sayehmiri K, Azami M, Nikpey S, Borji M, Sayehmiri F. Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage in Health Personnel of Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. Irje. 2015;11(3):1–10.

Acknowledgements

Hereby, we would like to thank the Ilam University of Medical Sciences for their support.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ilam University of Medical sciences. The funder had no role in the process of study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A, MR.HA, F. K, M. K, and H. N acquired the data. M. A analyzed and interpreted the data. M. A, MR.HA, F. K, M. K, and H. N and M. S drafted the manuscript; MA, MS, and MK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MK supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is not conflict of interest between the authors of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure 1- supplementary

: The sensitivity analysis for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian population.

Additional file 2: Figure 2-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian males.

Additional file 3: Figure 3-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of GERD symptoms in Iranian females.

Additional file 4: Figure 4-supplementary

: Publication bias for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of GERD symptoms.

Additional file 5: Figure 5- supplementary

: The sensitivity analysis for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of heartburn in Iranian population.

Additional file 6: Figure 6-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of heartburn in Iranian males.

Additional file 7: Figure 7-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of heartburn in Iranian females.

Additional file 8: Figure 8-supplementary

: Publication bias for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of heartburn.

Additional file 9: Figure 9- supplementary

: The sensitivity analysis for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian population.

Additional file 10: Figure 10-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian males.

Additional file 11: Figure 11-supplementary

: The daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of regurgitation in Iranian females.

Additional file 12: Figure 12-supplementary

: Publication bias for daily (A), weekly (B), monthly (C), and overall (D) prevalence of regurgitation.

Additional file 13.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimian, M., Nourmohammadi, H., Salamati, M. et al. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 20, 297 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01417-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01417-6