Abstract

Background

Little is known about the prognostic impact of cirrhosis on long-term survival of patients with combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC) after hepatic resection. The aim of this study was to elucidate the long-term outcome of hepatectomy in cHCC-CC patients with cirrhosis.

Methods

A total of 144 patients who underwent curative hepatectomy for cHCC-CC were divided into two groups: cirrhotic group (n = 91) and noncirrhotic group (n = 53). Long-term postoperative outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Results

Patients with cirrhosis had worse preoperative liver function, higher frequency of HBV infection, and smaller tumor size in comparison to those without cirrhosis. The 5-year overall survival rate in cirrhotic group was significantly lower than that in non-cirrhotic group (34.5% versus 54.1%, P = 0.032). The cancer recurrence-related death rate was similar between the two groups (46.2% versus 39.6%, P = 0.446), while the hepatic insufficiency-related death rate was higher in cirrhotic group (12.1% versus 1.9%, P = 0.033). Multivariate analysis indicated that cirrhosis was an independent prognostic factor of poor overall survival (hazard ratio 2.072, 95% confidence interval 1.041–4.123; P = 0.038).

Conclusions

The presence of cirrhosis is significantly associated with poor prognosis in cHCC-CC patietns after surgical resection, possibly due to decreased liver function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC) is a very rare entity that includes elements of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and represents 0.4–14.2% of primary liver malignancies [1]. Hepatic resection affords the best chance of long-term survival with a reported 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 23.1–54.1%. Vascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, satellite nodules, and tumor size were reported as prognostic factors [2–5].

Patients with cHCC-CC, especially in Asian countries, are frequently accompanied by liver cirrhosis, with a prevalence of 27.7–84.6% [6]. However, little is known about the prognostic significance of cirrhosis in cHCC-CC patients after surgery. In this study, we compared the long-term outcomes of hepatic resection in cHCC-CC patients with and without cirrhosis.

Methods

Patients

From February 2000 to December 2011, 151 patients with cHCC-CC who underwent curative resection at our institutes. Curative resection was defined as complete excision of the tumor with clear microscopic margin conformed by histopathological examination. Allen and Lisa [7] categorized cHCC-CC into three types; type A: HCC and CC exist separately (double cancer); type B: HCC and CC exist contiguously but independentlyonly; and type C: HCC and CC components show contiguity with intermingling. Histologically, only type C tumors that displayed the characteristics of a genuine mixture of both HCC and CC elements were regarded as true combined tumors [5]. Seven patients with Allen type A and B tumors were therefore excluded from the study. Finally, 144 patients were subjected to this study. Of them, 91 (63.2%) patients had cirrhosis as confirmed by histology and the remaining 53 (36.8%) patients did not have cirrhosis. Patient demographics, operative data, tumor characteristics, and follow-up findings were reviewed retrospectively. Postoperative morbidity and mortality were analyzed 90 days after operation. Liver dysfunction was defined as total bilirubin level >10 mg/dL unrelated to biliary obstruction or leak and/or the international normalized ratio >2 for more than 2 days after resection and/or clinically significant ascites/hepatic encephalopathy [8].

All patients were followed postoperatively by serum tumor marker (alpha-fetoprotein [AFP] and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 [CA 19–9]) analysis and ultrasound or computed tomography at least every 3 months in the first year after hepatectomy, and then at gradually increasing intervals. Intrahepatic recurrence was identified by new lesions on imaging with typical appearances of cHCC-CC with or without a rising serum AFP or CA 19–9 level. Determination of treatment strategy for recurrent tumors depended on the number and site of the tumors, any concurrent extrahepatic recurrence, liver function, and the general status of the patient. Re-hepatectomy and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (PRFA) were considered as first-choice treatments. Re-hepatectomy was performed for Child A patients with solitary or multiple tumors limited in the semi-liver with sufficient liver remnant volume. PRFA was given to Child A and selected Child B patients with solitary tumor ≦3 cm located deeply in the liver parenchyma or multiple tumors (up to 3 lesions all ≦ 3 cm) in different lobes without vascular invasion or gross ascites. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) was considered when the above two treatments were not possible, as in patients with advanced multinodular recurrent tumors, poor liver function, and insufficient liver remnant volume. Systemic chemotherapy or conservative treatment was considered for patients with extensive systemic recurrence and/or very poor liver function or general condition.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous data were compared by the χ 2 test and the Student t test, respectively. Patient OS and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were compared by log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed by the Cox proportional hazard regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 11.0; SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

The clinicopathologic data of noncirrhotic and cirrhotic patients are summarized in Table 1. Cirrhotic patients had higher prevalence of men, alcohol abuse, and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), higher serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, higher prevalence of abnormal serum AFP level, and smaller tumors than non-cirrhotic patients.

Regarding operative procedures and preoperative outcomes, less major resection (≥3 segments) was applied in cirrhotic patients. Postoperative morbidity was similar in the two groups except for the higher incidence of liver dysfunction in cirrhotic group. One patient in cirrhotic group died of hepatorenal failure resulting in a mortality rate of 1.1%, showing no statistically significant difference with 0% in non-cirrhotic group (Table 2).

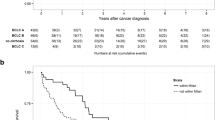

The median postoperative follow-up period was 35 (range 3–127) months. The 5-year DFS rate was similar between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients (29.6% versus 38.7%, P = 0.079). However, the 5-year OS rate and the median OS time in cirrhotic group was significantly lower than that in non-cirrhotic group, with values of 34.5% and 31 months, versus 54.1% and 63 months, respectively (P = 0.032) (Fig. 1).

By the time of analysis, recurrences developed in 68 cirrhotic and 35 non-cirrhotic patients with a similar frequency (75.5% versus 66.1%, P = 0.567). Also, there was no difference in the median time to recurrence and the pattern of recurrence between the two groups. Regarding the initial treatment for recurrences, aggressive approaches including re-hepatectomy and local ablation were applied less frequently in cirrhotic patients as compared with non-cirrhotic patients (36.8% versus 60.0%, P = 0.025) (Table 3).

Investigation on the cause of death showed that 56 cirrhotic patients and 23 non-cirrhotic patients died during the follow-up period in this study (P = 0.029). Cancer recurrence-related death was similar between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic group (46.2% versus 39.6%, P = 0.446), while hepatic insufficiency-related death was more frequently observed in cirrhotic group (12.1% versus 1.9%, P = 0.033).

Prognostic factors for overall survival

Univariate analysis showed that factors affecting OS were maximum tumor size > 5 cm, intraoperative transfusion, cirrhosis, bile duct invasion, lymph node involvement, and vascular invasion. Multivariate analysis showed that cirrhosis was an independent prognostic factor for poor OS (hazard ratio 2.072, 95% confidence interval 1.041–4.123; P = 0.038) (Table 4).

Discussion

The reported prevalence of cirrhosis in cHCC-CC patients ranges widely from 27.7% to 84.6% worldwide based on operative findings [6]. This figure is 63.2% in our cohort. The sex ratio of cHCC-CC shows a prominent male predominance, which is compatible with the findings of several previous reports [2–5]. It has been reported that this male predominance correlated with high activities of androgen axis, an oncogenic pathway involved in hepatocarcinogenesis [9]. However, further analysis of the precise mechanisms for male susceptibility to cHCC-CC is needed.

cHCC-CC is reportedly similar to HCC in terms of clinicopathologic characteristics including mean age, male/female ratio, hepatitis viral positivity, serum AFP level, and the presence of cirrhosis [1]. Some researchers from Asian institutions therefore speculated that cHCC-CC represents a variant of ordinary HCC that exhibits cholangiocellular metaplasia, rather than a true intermediate disease entity between HCC and CC [3]. As is the case with HCC, we find that hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a main etiologic factor in the development of cHCC-CC in a cirrhotic liver. Accordingly, ALT and ALT values as indicators of activity or severity of the hepatitis state were both higher in cirrhotic patients than those in non-cirrhotic patients. A comparison of the pathologic findings in resected specimens showed the tumor size was generally smaller in cirrhotic group. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that cirrhotic patients generally have active liver disease and may have image-based liver screening, which enabled detection of small tumors. However, it should be acknowledged that there may be a selection bias for hepatic resection. Many cirrhotic patients were unable to undergo hepatectomy because of poor liver function reserve, and most patients with large tumors may be treated by a nonsurgical modality such as hepatic artery embolization or conservative treatment.

As expected, cirrhotic patients had a significantly higher incidence of liver dysfunction after surgical resection. As cirrhotic patients have relatively small tumours and limited hepatic functional reserve, they usually undergo minor hepatectomy.

The negative impact of cirrhosis on long-term survival has been reported in postoperative HCC patients [10, 11], but its impact on long-term survival of cHCC-CC patients undergoing hepatectomy remains unclear. The present study is the first to present data to indicate that the cirrhosis is an independent predictor for postoperative OS of cHCC-CC patients. The 5-year OS rate was 34.5% in cirrhotic patients versus 54.1% in non-cirrhotic counterparts. This difference is likely attributable to more hepatic decompensation caused by ongoing cirrhosis itself in cirrhotic patients. As demonstrated in our study, hepatic insufficiency-related death accounted for 11 (12.1%) deaths in cirrhotic patients and only one (1.9%) death in non-cirrhotic patients. Difference in treatment strategies for recurrent disease may also account for differences in outcomes. Cirrhotic patients usually have impaired hepatic function after the initial hepatic resection, which limits the application of aggressive management for recurrence, which is often the leading cause for an unfavorable outcome.

Several studies have documented an association between cirrhosis and recurrence of HCC, which is likely attributable to multicentric de novo carcinogenesis in the remnant liver [10, 12]. However, our study failed to find such an association in cHCC-CC patients. One of the explanations for this discrepancy is that cHCC-CC with CC components exhibits a more aggressive behavior and has high probability of intrahepatic metastasis, which would overshadow the effect of cirrhotic liver related-carcinogenesis.

Theoretically, liver transplantation (LT) offers the potential benefit of resecting the entire tumor-bearing liver and eliminating cirrhosis simultaneously, and therefore it is generally believed to be an ideal approach for the treatment of cHCC-CC in cirrhotic patients. In the three cHCC-CC patients receiving LT reported by Chan et al. [13], one patient died from distant metastasis 16.5 months after operation while the other two patients survived 25 and 35 months after operation, respectively. Wu et al. [14] reported a 5-year OS rate of 39% in a case series of 21 patients with cHCC-CC treated with LT. Panjala et al. [15] reported a 5-year OS rate of 16% in their 12 cHCC-CC patients receiving LT. Employing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1988–2009), Garancini et al. [16] reported a 5-year OS rate of 41.1% in 16 cHCC-CC patients receiving LT. Currently, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of LT in the management of cHCC-CC because of insufficient data and limited evidence available.

Conclusion

This study showed that cHCC-CC patients with cirrhosis had a poorer long-term prognosis after surgical resection as compared with those without cirrhosis, possibly due to the decreased liver function.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CC:

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- cHCC-CC:

-

Hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DFS:

-

Disease-free surviva

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- LT:

-

Liver transplantation

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PRFA:

-

Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation

- TACE:

-

Transarterial chemoembolization

References

Kassahun WT, Hauss J. Management of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1271–8.

Jarnagin WR, Weber S, Tickoo SK, Koea JB, Obiekwe S, Fong Y, et al. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2002;94:2040–6.

Yano Y, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Sakamoto Y, Yamasaki S, Shimada K, et al. Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 26 resected cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:283–7.

Lee SD, Park SJ, Han SS, Kim SH, Kim YK, Lee SA, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma after surgery. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2014;13:594–601.

Tang D, Nagano H, Nakamura M, Wada H, Marubashi S, Miyamoto A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of Allen’s type C classification of resected combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a comparative study with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:987–98.

Zhou YM, Zhang XF, Wu LP, Sui CJ, Yang JM. Risk factors for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a hospital-based case–control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12615–20.

Allen RA, Lisa JR. Combined liver and bile duct carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:647–55.

Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Abdalla EK, Arens JF, Nemr RA, Wei SH, et al. Is extended hepatectomy for hepatobiliary malignancy justified? Ann Surg. 2004;239:722–30.

Wang SH, Yeh SH, Lin WH, Yeh KH, Yuan Q, Xia NS, et al. Estrogen receptor α represses transcription of HBV genes via interaction with hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:989–98.

Sasaki Y, Imaoka S, Masutani S, Ohashi I, Ishikawa O, Koyama H, Iwanaga T. Influence of coexisting cirrhosis on long-term prognosis after surgery in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 1992;112:515–21.

Zhou Y, Lei X, Wu L, Wu X, Xu D, Li B. Outcomes of hepatectomy for noncirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:236–42.

Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, Ohkubo T, Hasegawa K, Miyagawa S, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:200–7.

Chan AC, Lo CM, Ng IO, Fan ST. Liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma. Asian J Surg. 2007;30:143–6.

Wu D, Shen ZY, Zhang YM, Wang J, Zheng H, Deng YL, et al. Effect of liver transplantation in combined hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma: a case series. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:232.

Panjala C, Senecal DL, Bridges MD, Kim GP, Nakhleh RE, Nguyen JH, et al. The diagnostic conundrum and liver transplantation outcome for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1263–7.

Garancini M, Goffredo P, Pagni F, Romano F, Roman S, Sosa JA, et al. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a population-level analysis of an uncommon primary liver tumor. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:952–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yanfang Zhao (Department of Health Statistics, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China) for her critical revision of the statistical analysis section.

Funding

The design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript for this research was mainly supported by Foundation of Health and Family Planning Commission of Fujian Province of China (Project no.2013-ZQN-JC-31) and Nature Science Foundation of Shanghai (12ZR1440000).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

YZ and JY designed the study. YZ and CS supervised the study. XZ and BL collected data. YZ and JY analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study and the study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s human research committee of the First affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University and Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital of Second Military Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, YM., Sui, CJ., Zhang, XF. et al. Influence of cirrhosis on long-term prognosis after surgery in patients with combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol 17, 25 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-017-0584-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-017-0584-y