Abstract

Background

Hypertension is one of the most common chronic diseases with a low control rate globally. The effect of communication skills training contributing to hypertension control remains uncertain. The aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness of an educational intervention based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide in improving hypertensive management.

Methods

A cluster randomized controlled trial enrolled 27 general practitioners (GPs) and 540 uncontrolled hypertensive patients attending 6 community health centers in Chengdu, China. GPs allocated to the intervention group were trained by an online communication course and two face-to-face workshops based on Calgary-Cambridge guides. The primary outcome was blood pressure (BP) control rates and reductions in systolic and diastolic BP from baseline to 3 months. The secondary outcome was changes in GPs’ communication skills after one month, patients’ knowledge and satisfaction after 3 months. Bivariate analysis and the regression model assessed whether the health provider training improved outcomes.

Results

After the communication training, the BP control rate was significantly higher (57.2% vs. 37.4%, p < 0.001) in the intervention groups. Compared to the control group, there was a significant improvement in GP’s communication skills (13.0 vs 17.5, p < 0.001), hypertensive patients’ knowledge (18.0 vs 20.0, p < 0.001), and systolic blood pressure (139.1 vs 134.7, p < 0.001) after 3 months of follow-up. Random effects least squares regression models showed significant interactions between the intervention group and time period in the change of GP’s communication skills (Parameter Estimated (PE): 0.612, CI:0.310,0.907, p = 0.006), hypertensive patient’s knowledge (PE:0.233, CI: 0.098, 0.514, p < 0.001), satisfaction (PE:0.495, CI: 0.116, 0.706, p = 0.004), SBP (PE:-0.803, CI: -1.327, -0.389, p < 0.001) and DBP (PE:-0.918, CI: -1.694, -0.634, p < 0.001), from baseline to follow-up.

Conclusion

Communication training based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide for GPs has shown to be an efficient way in the short term to improve patient-provider communication skills and hypertension outcomes among patients with uncontrolled BPs.

Trial registration

The trial was registered on Chinese Clinical Trials Registry on 2019–04-03. (ChiCTR1900022278).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the most common chronic diseases in the world and the primary risk factor for cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction or stroke [1, 2]. But only 13.8% of patients with hypertension are under control worldwide [3], while 15.3% in China are controlled [4]. Anti-hypertensive medication can effectively reduce adverse outcomes. Factors such as self-efficacy, hypertension knowledge, patient satisfaction, and medication adherence may influence patients' decisions to use anti-hypertensive drugs [5, 6]. Studies have shown that effective doctor-patient communication may indirectly improve medical outcomes by targeting these factors [7, 8]. However, randomized control trials on whether communication skills training contributes to the hypertension control effect have shown inconsistent results [9,10,11,12].

A recent meta-analysis of six experimental trials in people with hypertension concluded that interventions to improve communication were likely to improve satisfaction, but there was little effect on secondary outcomes, such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure [13]. One of the main reasons for this unclear effect was the diversity of training interventions across studies: motivational interviewing, patient-centered care, shared decision making and other communication techniques [13]. Calgary-Cambridge Guide(C-CG), developed based on evidence in medical interviews, is a comprehensive and popular communication model in many countries, which integrates various components involving active listening, gathering information, empathy, shared decision making, etc. [14]. Studies have demonstrated that the Calgary-Cambridge Guide can effectively improve health providers’ communication skills [15, 16].

General practitioners (GPs) in China, similar to family physicians or GPs in other countries, have an integral role in providing active and continuous services for hypertensive patients in primary care settings, including health education, empowering patients, adherence monitoring and medication tailoring [17, 18]. Patients with hypertension in the community form longitudinal relationships with GPs through family doctor contracting program in China [19].

Therefore, we hypothesize that communication training based on C-CG for GPs may improve patients’ hypertension knowledge and healthcare satisfaction, thus positively affecting hypertension outcomes. Besides, our previous survey revealed that Chinese GPs exhibited a significant training need for improving their communication skills, specifically in building rapport, displaying empathy, and participating in shared decision-making, all encompassing in the Calgary-Cambridge Guide [20]. This study aimed to evaluate whether C-CG-based communication training can improve the communication skills of GPs and bring a positive impact on clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients.

Method

Setting

This cluster randomized controlled trial adhered to CONSORT guidelines and was conducted between September 2019 and March 2021 in Wuhou District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Six community health centers (CHCs) out of a total of thirteen CHCs of the Wuhou District, with seven rejected due to various reasons, such as participating other research program.

Participants

GPs were enrolled from selected CHCs if they (a) had obtained a qualified certificate for general practice, (b) provided health care services for hypertensive patients during the past year before the educational intervention and (c) agreed to be enrolled.

We recruited patients according to the ratio of 20:1 with GPs in each CHC with the following characteristics: (a) diagnosis of primary hypertension according to “Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension, 2018” [21];(b) aged 18 years or older; (c) prescribed at least one antihypertensive medication during the past 3 months. Patients were excluded if they (a) had secondary hypertension or had hypertensive emergency; (b) had mental disturbance, visual impairment, or mental disturbance; (c) were pregnant or lactating women.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants including the GPs and hypertensive patients.

Randomization and blinding

The recruited 6 CHCs were allocated (1:1) to either the intervention or the control group using a random number table generated by SPSS26. Due to the nature of the educational intervention, blinding of GPs was not feasible. However, patients were blinded to the GP's group allocation, and importantly, the evaluators assessing the outcome measures were also blinded to whether the patients were in the intervention or control group.

Intervention

The GPs in the intervention group completed six online theoretical learning sessions and two face-to-face workshops, all of which were developed by GP communication trainers based on the Calgary-Cambridge guidelines. Before the experimental study, our team consisting of 5 experienced GP trainers in communication, recorded an online communication course [22], which was developed according to the Calgary-Cambridge guide with details in Supplement I. Each session was accessed on the “Tencent Meeting App” and lasted around an hour, comprising a 30-min group viewing of instructional videos followed by a 30-min group online discussion among the GPs.

The two face-to-face workshops were scheduled for the GPs in the intervention group to practice the communication skills they had learned during the online theoretical learning sessions. The workshops were guided by a senior GP trainer, one taking place after GPs completed the first three online sessions, and the other taking place after once all six sessions had been completed. In this workshop, GPs were divided into four groups to participate in role-play exercises, interact with standardized patients—trained actors simulating real patient scenarios—and receive individualized feedback to refine their clinical and communication skills. Each workshop took 2.5 h. GPs in both intervention and comparison group were provided with the printed and electronic handbook of “Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension” [21].

Measures and outcomes

Patient and GP characteristics

Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, marital status, education, income, and medical insurance and GPs’ sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, education, work experience, and professional title, were both obtained through self-report at baseline. Patient’s clinical data were extracted from the EMR at baseline, including smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of hypertension, cardiovascular family history, comorbid conditions, diabetes, duration of diagnosis, and body mass index.

GP Communication skills

GP consultations with study participants by standardized patients were videotaped (Songdian 514KM/534KM; Shenzhen, China) at baseline and one month after the end of the training program. Two observers independently rated the communication skills using the validated instrument of SEGUE Framework [23]. The SEGUE Framework contains 25 items, which are classified into the five dimensions as follows: (1) Set the stage; (2) Elicit information; (3) Give information; (4) Understand the patient’s perspective; (5) End the encounter. Responses for all items range from 0 (unable to answer or no) to 1(yes) [23].

Hypertension knowledge

Patients’ hypertension knowledge was assessed by the Hypertension Knowledge-Level Scale (HK-LS) at baseline and 3 months follow-up. The HK-LS comprises 22 items, each a statement that respondents judge as correct or incorrect. Example items include 'Taking medication daily is necessary when blood pressure is elevated' and 'If untreated, elevated blood pressure can lead to stroke.' Scores ranging on the HK-LS is 0 to 22, with higher scores indicating higher levels of hypertension knowledge. Cronbach’s α of the overall scale was 0.82 [24].

Patient satisfaction

Satisfaction with general practice care was assessed using the the 23-item European Task Force on Patient Evaluation of General Practice (EUROPE), validated for its reliability and applicability in China [25]. This scale allows patients to express their satisfaction across various dimensions of care, rating each item on a five-point Likert scale from ‘1 = poor’ to ‘5 = excellent’. Examples of items from this scale are 'Listening to you', 'Offering you services for preventing' and ‘Interest in your personal situation’. Data were collected at baseline and 3 months follow-up.

Blood Pressure

We assessed patients’ BP at baseline and 3 months follow-ups using an automatic, portable machine (Omron HEM-757), validated according to international validation protocol. Three blood pressures were collected from each participant after sitting still for 5 min. The three measurements were averaged. The blood pressure readings were conducted by a member of the research team, ensuring consistency and reliability in the measurement process. BP control was classified as uncontrolled (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, or SBP ≥ 130 mmHg or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg if diabetic or chronic kidney disease) or controlled.

Sample Size

To detect a clinically relevant 5mmHg reduction of systolic blood pressure between groups after 3 months follows up, with an estimated standard deviation of 12.4mmHg based on previous communication researches [9, 26, 27] and 80% power at a 5% significance level, a minimum of 97 hypertensive patients per group was needed. With an inflation factor of 1.95 for the cluster design, assuming a cluster size of 20 patients and an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.05 (for GP level) [28, 29], 190 patients per group were needed. To allow for 10% attrition, the arm was to include 211 patients in each group.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (Chicago, IL, USA). All outcomes were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle (ITT) [30]. The variable’s primary features were described as mean, standard deviation (± SD), median, interquartile range (IQR) or proportions (%). First, we used bivariate analyses (T-Test, chi-square or Mann–Whitney U) to test significant differences between clinical characteristics and socio-demographics in intervention and control groups in Table 2.

We conducted the random-effects least squares regression model to account for clustering patients within GP. This model included the main effects of study arm assignment (control vs. intervention), period (baseline vs. follow-up), their interaction and adjusted the patient demographics characteristics. SPSS 22 (Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 3.0.2 produced accurate estimates. A P value of 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

GPs and patients’ characteristics

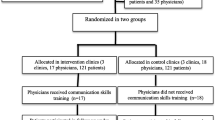

Figure 1 describes the flow of GPs and patients’ completeness of data. A total of 27 GPs were enrolled in the training program. Most GPs were female (62.96%), with a median age of 40 and more than ten years of work experience at selected six community health centers (Table 1). The hypertensive patients enrolled onto the study had a mean age of 64.81 ± 10.74 years and were mostly male (52.78%), married (87.78%), had less than junior high school education (61.11%), and had a median income of 3000 yuan monthly. Clinically, some patients also had a diagnose of diabetes (35.93%) and other comorbid conditions (20.19%), had a median time since hypertension diagnosis of 7 years, family history of hypertension (48.3%) and cardiovascular events (6.85%). (Table 1). At baseline, there was no difference in the total score of GP communication skills and the hypertension knowledge, medication adherence, systolic blood pressure of patients in both study groups. However, there were significant differences in GPs’ age ( p < 0.001), and patients’ income (p = 0.001), cardiovascular family history (p = 0.035), satisfaction with health care (p < 0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (p < 0.001) of hypertensive patients (Tables 1 and 2).

Educational intervention outcomes

We found that GP’s communication skills significantly differed in the change of total communication scores from baseline to follow-up in the intervention compared to the control group (Median: 2.50 vs 0.0, p < 0.001). However, the duration of clinical encounters demonstrated no significant differences (Median: -7.50 vs 78.00, p = 0.451).

After the intervention, BP control rate was significantly increased (57.2% vs 37.4%, p < 0.001). A significant difference was found between hypertensive patients of intervention versus control groups at follow-up and in change from baseline to follow-up in all the scores, including hypertension knowledge, medication adherence, and SBP (Table 2).

These results were in agreement with the random effects least squares regressions models which showed significant interactions between intervention group and time period. Thus, we found significant evidence in the change in GP’s communication skills (Parameter estimated(PE):0.612, CI:0.310,0.907, p = 0.006), hypertensive patient’s knowledge (PE:0.233, CI: 0.098, 0.514, p < 0.001), satisfaction (PE:0.495, CI: 0.116, 0.706, p = 0.004), DBP (PE:-0.918, CI: -1.694, -0.634, p < 0.001), from baseline to follow-up, in the intervention compared to the control group (Table 3).

Discussion

We found that brief communication training based on Calgary-Cambridge guides for GPs could directly impact hypertensive patients’ knowledge and satisfaction over a 3 month period. Moreover, the intervention may have an indirect effect on hypertensive outcomes in the short term (e.g., SBP, DBP and BP control rate). Our findings also included improving providers’ communication skills while not extending consultation time after the education program.

Patients with hypertension typically communicate with GPs several times a year following diagnosis. Thus, the quality of these encounters can be a significant determinant of the quality of their clinical outcomes. Our findings verify the hypothesis proposed by Street [7] that patient-provider communication can directly impact patients’ BP. However, it often operates indirectly through proximal and intermediate outcomes, such as patient understanding, satisfaction, and treatment adherence [7, 31]. These results are in line with recent RCTs, which demonstrate that educational communication programs have had an impact on patient’s clinical outcomes in primary care settings after six months of follow-up, including reduction of systolic blood pressure and improvement of medication adherence [9, 26].

However, several similar studies failed to show positive results [11, 12, 32]. It is noteworthy that these studies either had longer follow-up times, ranging from 12 to 20 months, or shorter training lengths with 4–6 h compared to studies with positive findings [9]. It’s likely that the effects of “low intensity” intervention could not be sustained over time [33]. Our findings also contrasted with recent systematic reviews [13], including 6 RCTs on hypertension that showed communication skills training interventions for healthcare professionals did not improve BP control or other relevant patient outcomes. Due to the diversity of training intervention, training theory, training methods, trainers, training assessment, training length and follow-up time, the pooled results should be treated cautiously [13]. In addition, communication training methods of included studies contained motivational interviewing, patient-centered care and shared decision-making. However, our study was based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide, which proved to be evidenced, comprehensive and integrated with interviewing content and process [14]. It contains multiple communication elements, such as patient-centered care, empathy, and shared decision making, which might be the reason why the Calgary-Cambridge communication model could potentially alter medical outcomes in our study within three months.

Consistent with the findings of similar intervention studies [9, 12], our study found that GPs who received communication training were able to significantly enhance patient satisfaction and knowledge regarding hypertension management. This aligns with observations from a cross-sectional study [34] that highlighted hypertensive patients' appreciation for physicians' communication behaviors such as 'active listening,' 'speaking in a way the patient can understand,' and 'paying attention to the patient.' These behaviors foster a deeper patient involvement and shared decision-making, which are crucial for effective self-care. Two hypertensive studies [35, 36] found a positive correlation between physician–patient relationship satisfaction and medication adherence. Although direct measures of medication adherence were not included in our study's results, the emphasis on communication skills in our intervention likely serves as a mediator by improving patient engagement and potentially influencing better self-care practices. This suggests that well-informed patients, who feel supported by their healthcare providers, may be more motivated to adhere to treatment regimens, thus indirectly contributing to improved blood pressure control.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first randomized controlled trial to estimate the potential impact of Calgary-Cambridge guides’ communication training for GPs on health outcomes in the hypertensive population. Besides the novel but generic training contents, the interventions incorporated several successful features of previous educational interventions, including multiple training methods and moderate training intensity in a relatively long period, which could potentially help maintain the training effect for GPs [13]. The intervention may still be effective during global pandemics, if training were to be delivered fully online. Thus, the training could be easier to encourage widespread implementation and potentially become a scalable approach. Further, our work documents the relationships between main covariates such as patients’ satisfaction, hypertension knowledge, and medication adherence that could help to explain better a modifiable mechanism between effective providers–patient communication and BP control for hypertensive patients [7, 31].

Some limitations are worth noting in this study. First, there was evidence of an imbalance between the intervention and control groups due to cluster randomization at baseline, both in GPs and patients. This may reflect post-randomization recruitment bias and reduce the power of detecting intervention effects. To minimize these effects, we used random effects, least squares, and regression models. Also, we included a wide range of factors that we considered may be associated with hypertensive outcomes and adjusted for potential confounders. Furthermore, this trial only had a small number of practices (6 clusters) from one region. GPs who took part were self-selected and thus likely to be more interested in communication. The external validity of our results may be limited, and the results should be interpreted with caution without further validation of these findings. On the other hand, it could be considered that GPs’ commitment to the subject matter is always necessary for effective learning. The third limitation is that we failed to collect and compare the hypertensive medications taken by both groups, especially after the intervention, which could be a confounding factor influencing blood pressure.

Conclusion

Communication training for GPs based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide could not only enhance patient-provider communication skills, but also altered satisfaction, hypertension knowledge, and blood pressure control in the short term. Our training program provided a feasible and evidence-based method in Chinese primary care settings in hypertension management and it should be encouraged as a method of continuing professional development. Future long-term follow-up studies are required to determine whether the effects are sustainable and lead to reduced cardiovascular outcomes. In the meantime, this generic communication training could be implemented in general practice to other similar chronic diseases, such as diabetes and asthma, which need to be examined in future studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and ethical reason but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GPs:

-

General practitioners

- C-CG:

-

Calgary-Cambridge Guide

- CHC:

-

Community health centers

- HK-LS:

-

Hypertension Knowledge-Level Scale

- EUROPEP:

-

European Task Force on Patient Evaluation of General Practice

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Inter quartile range

- SBP:

-

Systolic Blood Pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- BP:

-

Blood Pressure

- SEGUE:

-

Communication skills of set elicit give understand end framework

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England). 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, Yin P, Zhu J, Chen W, Li X, Wang L, Wang L, Liu Y, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394(10204):1145–58.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, Chen J, He J. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–50.

Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G, Zhang Z, Shao L, Tian Y, Dong Y, Zheng C, et al. Status of hypertension in China: results from the China hypertension survey, 2012–2015. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2344–56.

Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Elnour AA. Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96(4):e5641.

Appleton SL, Neo C, Hill CL, Douglas KA, Adams RJ. Untreated hypertension: prevalence and patient factors and beliefs associated with under-treatment in a population sample. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27(7):453–62.

Street RL Jr. How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(3):286–91.

Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

Tavakoly Sany SB, Behzhad F, Ferns G, Peyman N. Communication skills training for physicians improves health literacy and medical outcomes among patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):60.

Tavakoly Sany SB, Peyman N, Behzhad F, Esmaeily H, Taghipoor A, Ferns G. Health providers’ communication skills training affects hypertension outcomes. Med Teach. 2018;40(2):154–63.

Manze MG, Orner MB, Glickman M, Pbert L, Berlowitz D, Kressin NR. Brief provider communication skills training fails to impact patient hypertension outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(2):191–8.

Tinsel I, Buchholz A, Vach W, Siegel A, Dürk T, Buchholz A, Niebling W, Fischer KG. Shared decision-making in antihypertensive therapy: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:135.

Yao M, Zhou XY, Xu ZJ, Lehman R, Haroon S, Jackson D, Cheng KK. The impact of training healthcare professionals’ communication skills on the clinical care of diabetes and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):152.

Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, Draper J. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):802–9.

Iversen ED, Wolderslund M, Kofoed PE, Gulbrandsen P, Poulsen H, Cold S, Ammentorp J. Communication skills training: a means to promote time-efficient patient-centered communication in clinical practice. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2021;8(4):307–14.

Meehan MP, Menniti MF. Final-year veterinary students’ perceptions of their communication competencies and a communication skills training program delivered in a primary care setting and based on Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory. J Vet Med Educ. 2014;41(4):371–83.

Zhou T, Wang Y, Zhang H, Wu C, Tian N, Cui J, Bai X, Yang Y, Zhang X, Lu Y, et al. Primary care institutional characteristics associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in the China PEACE-Million Persons Project and primary health-care survey: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(1):e83–94.

Li X, Lu J, Hu S, Cheng KK, De Maeseneer J, Meng Q, Mossialos E, Xu DR, Yip W, Zhang H, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10112):2584–94.

Yuan B, Balabanova D, Gao J, Tang S, Guo Y. Strengthening public health services to achieve universal health coverage in China. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2019;365:l2358.

Lili DXL, Chuan Z, et al. Training needs and influencing factors of general practitioners’ communication skills under the synergy of health care system and medical educational system. Chin Gen Pract. 2021;24(13):1690–6.

Alliance CH. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension in China (2018 Revision). Chinese Journal of Cardiology. 2019;24(01):24–56.

Zou Chuan, Liao Xiaoyang: Communication skills in general practice; 2018. https://www.chengyiyuancheng.com/cyyc/html/course.html?name=%E6%B2%9F%E9%80%9A.

Makoul G. The SEGUE Framework for teaching and assessing communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(1):23–34.

Erkoc SB, Isikli B, Metintas S, Kalyoncu C. Hypertension Knowledge-Level Scale (HK-LS): a study on development, validity and reliability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(3):1018–29.

Chengwei THZ. Reliability and validity analysis of European satisfaction survey scale(EUROPEP) and its application in a community in Shanghai. Chinese Community Doctors. 2017;33(13):147–8.

Ma C, Zhou Y, Zhou W, Huang C. Evaluation of the effect of motivational interviewing counselling on hypertension care. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(2):231–7.

Okada H, Onda M, Shoji M, Sakane N, Nakagawa Y, Sozu T, Kitajima Y, Tsuyuki RT, Nakayama T. Effects of lifestyle advice provided by pharmacists on blood pressure: The COMmunity Pharmacists ASSist for Blood Pressure (COMPASS-BP) randomized trial. Biosci Trends. 2018;11(6):632–9.

Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1292–300.

WF M: Assessment of sample size and power for the analysis of clustered matched-pair data; 2007.https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/61320491.pdf.

Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomisation Trials in Health Research. London: Hodder Arnold; 2000.

Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Bone LR, Larson SM, Miller ER 3rd, Barr MS, Levine DM. A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1297–304.

Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007;45(4):340–9.

Świątoniowska-Lonc N, Polański J, Tański W, Jankowska-Polańska B. Impact of satisfaction with physician-patient communication on self-care and adherence in patients with hypertension: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1046.

Mahmoudian A, Zamani A, Tavakoli N, Farajzadegan Z, Fathollahi-Dehkordi F. Medication adherence in patients with hypertension: Does satisfaction with doctor-patient relationship work? J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:48.

Chang TJ, Bridges JFP, Bynum M, Jackson JW, Joseph JJ, Fischer MA, Lu B, Donneyong MM. Association between patient-clinician relationships and adherence to antihypertensive medications among black adults: an observational study design. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(14):e019943.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the general practices and patients participating in this study. In addition, thanks to Prof. Kang Deying, prof. Zhang Yonggang and Mr. Li Zhichao for statistical assistance, careful guidance and helpful discussion.

Funding

Project of Sichuan provincial health and family planning commission (No. 18PJ526), National educational research project of general practice(B-YXGP20210102-03), Research project of Science & Technology department of Sichuan Province (No. 2023YFS0027) and Scientific research project of Sichuan Medical Association.

This project was funded by Medical Education Research Project 2018, the Chinese Society of Medical Education, the Chinese Medical Association(2018B-N03018), and Scientific research

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZC and LXY contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. ZQ and DLL contributed to the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data and revising the manuscript. Data collection was carried out by LJZ, DH, ZY, GR, and LXL, YR, SHQ carried out the main analyses. JS, YR, and ZQ critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (10th version, October 2013).32 Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, on 2018–12-24. (No. 2018 (493)). All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the trial.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, C., Deng, L., Luo, J. et al. The impact of communication training on the clinical care of hypertension in general practice: a cluster randomized controlled trial in China. BMC Prim. Care 25, 98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02344-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02344-1