Abstract

Background

The prevalence of obesity has been increasing worldwide and is associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality. Weight management can reduce the risk of complications and improve the quality of life of patients with obesity. This study explored primary care physicians’ (PCPs’) attitudes and knowledge about weight management.

Methods

An anonymous questionnaire was distributed to 400 PCPs between 2020 and 2021. The survey included questions on treatment approaches (pharmaceutical and surgical) and items regarding the respondents’ demographic characteristics. We compared PCPs with low or high proactivity toward weight management. We explored attitudes and knowledge with the chi-square test for categorical variables or the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables.

Results

A total of 145 PCPs answered our survey (a response rate of 36.25%). More than half (53.8%) of the respondents showed low proactivity toward weight management in their practice. Proactive respondents were more likely to believe that pharmaceutical treatment effectively reduces weight and offered medical and surgical treatment options more frequently to their patients. Lack of knowledge was the most predominant reason for PCPs avoiding offering treatment to their patients, especially in less proactive PCPs (33.3% vs. 5.3%, p-value < 0.001). When comparing different pharmaceutical options, 46.6% of PCPs report they tend to prescribe liraglutide to their patients compared with only 11% who prescribe orlistat and 10.3% who prescribe phentermine (p-value < 0.001).

Conclusions

Many PCPs still do not actively provide obesity treatment despite improved awareness and therapeutic options. PCPs’ proactivity and attitudes are vital to this effort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity is a chronic disease whose prevalence has increased in recent years and is considered a global epidemic. In 2015, about 108 million children and about 604 million adults worldwide were categorized as obese [1]. In the United States, 41.9% of individuals over 20 are obese, and in those aged 2–19, the prevalence of obesity is 19.7% [2]. A recent report in Israel provided data about the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Israel [3]; 34% of adults between 20 and 64 were classified as overweight, and 25.1% were classified as obese as of 2021. In the same report, the prevalence of overweight among children and adolescents was 19.6% and 29.3%, respectively, and for obesity, 7.7% and 12%, respectively. Compared to earlier data, notably from 2013, a marked increase in rates of obesity was reported [3].

Obesity is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, etc. [4, 5]. An increase in body mass index (BMI) directly correlates with an increase in morbidity [6]. Among patients with obesity, weight reduction has been proven to improve health outcomes and decrease morbidity and mortality [7, 8]. Studies have shown that even a slight weight loss can reduce morbidity [9]. Moreover, well-timed intervention can potentially reverse specific morbidities, such as pre-diabetes [10].

Weight loss can be achieved by several means, including nutrition, psychological, behavioral, pharmaceutical, and surgical treatment. Weight loss is aimed to prevent and treat the complications of obesity and improve patients’ quality of life. By clinical standards, a successful outcome constitutes a decrease of more than 5% in body weight, reducing complications and improving quality of life [11]. As a first step, patients should be referred for training on lifestyle alterations, including dietary changes, physical activity, and behavioral changes. However, this option is not feasible for all, and many struggle to maintain it.

In such patients, and particularly in patients with persistent obesity and weight-related morbidity, a pharmaceutical option can be considered. This is intended for patients with a BMI higher than 30 or a BMI between 27 and 29.9 who have comorbidities [12]. In Israel, three agents are approved for obesity treatment - Liraglutide, Phentermine, and Orlistat. The much-discussed Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 agonist) Semaglutide (Ozempic) is not officially indicated for obesity in Israel and is therefore not included in this study. An additional option for weight loss is surgical intervention. In Israel, bariatric procedures are usually offered to patients with a BMI of over 40 or over 35 if there are comorbid conditions. This method is highly effective and may even produce weight loss of dozens of kilograms in some patients and significant improvements in comorbid conditions [13,14,15].

Knowledge and attitudes of physicians in treating obesity

Due to the risks of obesity and the ensuing importance of treating it, it has been long perceived as a matter to be medically discussed by professionals in the field. Different studies explored physicians’ knowledge and attitudes in treating obesity; A study performed in the United States in 2011 reported a difference between physicians practicing in rural communities and those practicing in urban communities. Additionally, a study conducted in Hungary in 2013 reported that only 50% of primary care physicians (PCPs) were familiar with the criteria for obesity treatment. Factors such as training stage, demography, age, and BMI affected attitudes and selection of therapeutic options [16].

A cross-sectional study performed in 2021 in eight European countries reported that most physicians believed that treating obesity in patients with comorbidities was a top priority [17]. However, most physicians selected a lifestyle change; only 30% added pharmaceutical therapy. The common reasons for underprescribing pharmaceutical options were lack of knowledge and concerns about the safety of such options (41%), believing that pharmaceutical treatment should be prescribed by another specialist physician (12%), and not believing in this therapeutic option (13%). In a thematic analysis regarding weight management discussion with patients, some of the obstacles physicians faced were pessimism about weight loss success and physicians’ feelings of hopelessness and frustration regarding the treatment [18].

An Israeli study from 2002 suggested that only 66% of PCPs knew the indication for prescribing pharmaceutical agents, and only 4% actually recommended such treatment to their patients [19]. This sole study performed in Israel highlights the importance of the current study. In 2002, awareness of obesity was still in its infancy, and pharmaceutical options were few and ill-reputed. In the years since some agents were removed due to safety issues (such as Lorcaserin and Sibutramine), safer and more efficient options were introduced.

As new medications for weight management are being introduced constantly [20, 21], PCPs are handling many patients who seek these treatments but do not always feel sure enough to provide them. This study aimed to investigate the attitudes and knowledge of PCPs to weight management and to characterize proactive PCPs in this area.

Methods

Study design and setting

In this cross-sectional descriptive study, we distributed surveys to PCPs throughout Israel. Between 2021 and 2022, we offered 400 PCPs to answer our survey, and 145 physicians filled out the questionnaire (a response rate of 36.25%). Participants were not offered incentives to partake. The study was approved by the ethical committee of MHS (0064-21-MHS). Informed consent was granted by submission of a completed questionnaire.

Participants

The sample in this study was a convenient sample. We distributed the survey during professional conferences, continuing medical education activity, and online professional forums. Only physicians who actively provided direct patient care during the survey period were invited to participate. The survey was open to both specialists and residents. We did not limit the participation based on the number of weekly hours or years of experience.

Questionnaire

We could not find a questionnaire suitable for our study’s purpose. We formulated and validated a questionnaire through a face-validity process with five different PCPs. The questionnaire has several parts:

-

a.

Attitudes towards weight management: Section A, questions 2–8, 11–12 and 16.

-

b.

Agreement of the respondents to clinical scenarios in which they would or would not prescribe pharmaceutical therapy – Section A, question number 9 (11 options).

-

c.

Knowledge enhancers – Section A, question 10.

-

d.

Attitudes toward different drug agents (liraglutide, phentermine, and xenical) – Section A, questions 13–15.

-

e.

Demographic questions – Section B, questions 1–13.

Burris et al. suggested that a proactive approach to managing health behaviors (in their paper, smoking cessation) includes three dimensions: identify the population, offer treatment, and deliver treatment [22]. This model is also relevant for weight management. We defined a proactive PCP as one that identifies his patients with obesity (weighs his patients, initiates a discussion about the subject), offers treatment for it (lifestyle changes/pharmaceutical/bariatric surgeries), and can deliver the treatment himself (when relevant). Proactivity was based on seven items from the questionnaire (2.6, 3.3, 4–6, 12, and 16), with a score between 0 and 8 (see supplementary material for the English translation of the questionnaire and the score). High proactivity was defined as a score above 4.

Sample size calculations

In order to describe a phenomenon with an assumed proportion of 25%, a confidence level of 95%, and an acceptable difference of 8%, we needed 145 respondents. To compare two proportions (45% vs. 20%) with a significance level of 5% and 80% power, we needed 124 respondents (62 in each group). Sample size calculation was done using Winpepi.

Statistical analysis

Survey responses were analyzed using SPSS version 28. Descriptive statistics was used; for categorical variables, numbers, and percentages, and for continuous variables, mean and standard deviation. We used univariate analysis to examine the differences between proactive and non-proactive PCPs and the difference in their attitudes using a chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney for continuous variables with the non-parametric distribution. Logistic regression was used for multivariate modeling. For the age and sex variables, we used the ENTER approach, and for all other variables, we used the FORWARD approach.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The average age of the respondents was 41.6 (± 10.6), with a median value of 38. Women made up 55.8% of the respondents (82/147). 52% were specialists at various stages. On average, the respondents had 10.6 years of experience (± 11.2) and a median of 6 years. 66.4% were graduates of Israeli universities. 15% of the respondents were independent PCPs (fee for service) (n = 23). Almost 54% (76/145) of respondents showed low proactivity (having a low initiative to treat obesity). We did not find significant differences between highly proactive and less proactive PCPs (Table 1). The Cronbach alpha index of the proactivity scale was 0.504.

Univariate analysis

In univariate analysis, no statistically significant differences were detected between proactive and non-proactive PCPs, including in age, gender, weight, or personal experience with trying to lose weight. In addition, the type of specialization, years of seniority, type of clinic, employment status, country of study, and socioeconomic status (SES) of the patients did not affect the tendency to be proactive in treating obesity. Only 0.02% (n = 3) of PCPs tried pharmaceutical therapy themselves. In a multivariate analysis, no variable was significantly correlated with proactivity (age: OR-1.02, 95 CI 0.98–1.05, p-value-0.377; Gender, female: OR-0.63, 95% CI 0.31–1.28, p-value-0.200).

Attitudes toward weight management

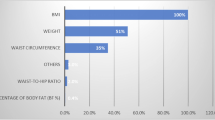

We found significant differences in the attitudes toward managing obesity and the proactivity of the physician (Table 2). Proactive PCPs believed that pharmaceutical treatment reduces weight more effectively than non-proactive PCPs (81.6% vs. 53.6%, p-value = < 0.001, respectively). The proactive physicians also offered medical and surgical treatment more frequently to their patients when compared to the non-proactive physicians (65.3% vs. 28.4%, p-value < 0.001 and 13.7% vs. 3%, p-value-0.024, respectively). Proactive PCPs offered medication to a significantly wider variety of patients compared to less-proactive physicians (Fig. 1); patients with a BMI higher than 30 (63.2% vs. 42%, p-value = 0.011), patients who have a low response to lifestyle changes (67.1% vs. 46.4%, p-value = 0.012), patients over the age of 60 (39% vs. 13%, p-value = < 0.001) and young people under the age of 30 who suffer from obesity (36.8% vs. 20.3%, p-value = 0.028). PCPs defined as less proactive claimed that they do not offer pharmaceutical treatment due to the lack of knowledge on the subject (33.3% vs. 5.3%, p-value = < 0.001). Not surprisingly, almost 100% of PCPs in both groups suggested lifestyle modifications for their patients with obesity.

As for attitudes regarding improving knowledge and learning about obesity treatment (Table 3), 84% of survey respondents (n = 123) believed that personal experience with patients would improve knowledge and therapeutic approaches. We found that 68% of PCPs offered such treatment at least once a month, and 23% offered it weekly. When asking PCPs what would encourage them to offer more patients treatment for obesity, the most important factors were research that proves the effectiveness of the pharmaceuticals (86.8%) and clear guidelines published by the professional union (82.7%). In contrast, only 12% (n = 18) responded that information published to the general public would affect their approach and treatment of obesity.

As for the difference in PCPs’ attitudes to various pharmaceutical agents, statistically significant differences were detected in all the parameters between the three agents tested - liraglutide, phentermine, and orlistat (Fig. 2). Almost half of the PCPs claimed that Liraglutide had good efficacy, compared to 13% and 9% for Phentermine and Orlistat, respectively (p-value < 0.001). The medication used by most PCPs was Liraglutide (46%). In the price category, Liraglutide was perceived as expensive by 76% of PCPs compared to Phentermine (10%) and Orlistat (11%). Orlistat and Phentermine were perceived as having significant side effects (53% and 60%) compared to Liraglutide (26%). Regarding the knowledge of the PCPs, Orlistat (24%) and Phentermine (21%) were considered by more PCPs than Liraglutide as treatments they are not familiar with (4%).

Discussion

This study examined the current attitudes of PCPs in Israel toward managing obesity. The study provides insight into the factors influencing PCPs’ decisions. PCPs are well familiar with obesity treatments and are willing to see this issue as part of their responsibility. Similar results were observed in studies conducted in Europe and Israel in recent years [17, 19]. Despite the awareness of obesity as a medically relevant issue, only 76% of the respondents thought treating it was their responsibility, and they initiated only half of the conversations on the subject. This is in line with other studies that suggest that although most physicians agree that obesity is a chronic disease, most physicians wait for the patient to broach the subject of weight management [23,24,25].

Obesity treatment is multilayered, and the first line of treatment, according to the guidelines, is lifestyle modification. As we saw in the study results, almost 100% of PCPs suggested their patients with obesity make lifestyle modifications. Similar results were observed in an Israeli study that examined the attitudes of PCPs in Israel on the subject in 2002 [19]. The similarities between studies conducted more than twenty years apart, with drastically different obesity rates and weight management options, may suggest physicians are comfortable and familiar with this option. When assessing which dietary advice for weight management PCPs tend to give, the most prevalent is reduced caloric intake, but intermittent fasting and ketogenic diet are also quite popular [26].

Additionally, this study examined the familiarity and prescription practices of pharmaceutical options for weight management among PCPs in Israel. We report that most physicians do so on a monthly basis, at least. Almost two-thirds of proactive PCPs offer pharmaceutical options to their patient compared to less proactive PCPs, who offer it to 28%. This may result from their familiarity and confidence in the agents, particularly in liraglutide, a GLP-1 analog. Compared to the Israeli study from 2002, where only 4% of PCPs indicated that they usually prescribe medication for obesity, the US data from 2018 were even lower [27]. This trend may very well result from the trajectory of use and experience. Very early weight loss agents were revealed to be unsafe after they were tested and sometimes marketed; this may have instilled suspicion in physicians looking to safeguard their patients. The case of Liraglutide, however, has allowed physicians to familiarize themselves with the agent as a treatment for diabetes mellitus before its use for other indications. Studies and years of clinical experience have expanded the range of safe and effective therapeutic options, and trends seem to corroborate this. This may also be a consequence of rising obesity rates and concern for associated comorbidities.

As for bariatric surgeries, only 13.7% of proactive PCPs offer this option, compared to even less among less proactive PCPs (3%). This is in line with other studies that suggested that PCPs avoid referring patients to these operations due to overestimation of complications and mortality and the feeling of lack of confidence in treating these patients after the surgery [28].

Comparing the demographic variables that differentiate the groups, no statistically significant differences were found. We assume that there is a knowledge gap between the groups that accounts for the difference between them. PCPs with low proactivity claimed that they do not choose pharmaceutical treatments because of the lack of knowledge. In contrast, proactive PCPs know more about the treatment and its potential drawbacks. Studies show knowledge gaps for weight management options and guidelines and the need of PCPs for more training on obesity [23, 29]. This trend is quite nuanced, as proactive professionals may be more inclined to educate themselves on the matter. Whether the knowledge, or lack thereof, is a consequence of proactivity or its source, it is clear that physicians hesitate to operate where they feel they are not well informed. In such cases, the proactivity of physicians may be encouraged by continued education and discourse, should the need arise.

The finding further highlights that over 80% of PCPs claimed that publishing clear guidelines would make them offer more pharmaceutical treatment to patients. The last time the Israeli Medical Association published such guidelines was in 2003. Such guidelines are almost obsolete, given the new options and the changing trends.

In a Canadian review on improving primary care obesity prevention and management, the authors concluded that a multifactorial approach is needed at the level of education, health policy, and public health; this includes overcoming knowledge gaps and equipping the physician with relevant skills to treat obesity [30]. This means continued education efforts must be done proactively to introduce the full range of therapeutic options. Guidelines should be produced and distributed so physicians feel supported and confident in suggesting pharmaceutical treatment [24].

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of a validated instrument is a major barrier since the results of this study cannot be compared with similar studies. Second, self-report questionnaires are inherently biased and may be swayed by professional and personal circumstances. A selection bias is possible, as PCPs with a higher awareness of obesity are more likely to participate. The response rate is 36%, which might be viewed as low. However, it is similar to other published PCPs’ surveys. Third, the rapid changes in the field with the introduction and overnight popularity of such agents as Semaglutide are left out of this study. Fourth, obesity management is the work of a multidisciplinary team (physicians, dietitians, psychologists, social workers, etc.). Therefore, future studies should evaluate not only physicians but also other related healthcare workers. Finally, when treating obesity, physicians should try to remain unstigmatized, although, from former studies, this is not the case [31]. This study did not ask about stigmatic attitudes regarding obesity, which may influence attitudes and behavior.

However, this study has several strengths which benefit and enrich the discipline. Primarily, this study addresses physicians’ attitudes, which are sometimes neglected when discussing weight management. While the quest for better health is individual and personal, therapeutic alliances and medical care should and often partake in this process. Additionally, PCPs are a subset of medical professionals who are often the first and most consistent source of medical advice in patients’ lives, rendering them especially valuable in chronic conditions management. The results of this study can be generalized to other primary care practices in developed countries because obesity treatment options (medications and surgeries) are similar. In addition, as seen in the literature, the same obstacles are encountered in many countries when approaching obesity treatment. Yet, cultural and ethnic differences may exist in different countries, which may influence the generalizability of our findings. Lastly, this study explored physicians’ attitudes towards various means of weight loss and management and thus revealed that the aim of weight loss is important in their mind; their obstacles lie in the appropriate mean. This distinction leaves room for intervention and, thus, potentially better care for patients.

Conclusions

While this study aimed initially to pinpoint the demographic characteristics correlated with increased proactivity in obesity treatment, the resulting findings suggest that the obstacles in such treatment lie not in the individual physician but in the knowledge at their disposal. PCPs feel very confident suggesting lifestyle changes but feel less confident when offering pharmaceutical treatments and even less confident when offering bariatric surgeries to their patients. Our findings suggest that PCPs may be better equipped and empowered to expand the range of therapeutic options for weight management by continuing education and providing them with clear guidelines for weight management.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- GLP-1 agonist:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

- PCPs:

-

Primary care physicians

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

References

MH AA, MB F. R, P S, K E, A L, Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2017 Jul 6 [cited 2023 Aug 15];377(1):13–27. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28604169/.

Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD, Chen TC, Davy O, Fink S et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. Natl Health Stat Report [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Aug 15];2021(158). Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273.

Rabinovich M, Minikandem Giveon Y, Overweight J. ; 2023 Feb [cited 2023 Dec 24]. Available from: https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/684bbcd7-49a5-ed11-8157-005056aa4246/2_684bbcd7-49a5-ed11-8157-005056aa4246_11_19991.pdf.

Khaodhiar L, McCowen KC, Blackburn GL. Obesity and its comorbid conditions. Clin Cornerstone [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2023 Dec 24];2(3):17–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10696282/.

Liu N, Birstler J, Venkatesh M, Hanrahan L, Chen G, Funk L. Obesity and BMI Cut Points for Associated Comorbidities: Electronic Health Record Study. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Dec 24];23(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34383661/.

Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Impact of body mass index on prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: cohort study. Fam Pract [Internet]. 2014 Feb [cited 2023 Dec 24];31(1):38–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24132593/.

Tahrani AA, Morton J. Benefits of weight loss of 10% or more in patients with overweight or obesity: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring) [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Dec 24];30(4):802–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35333446/.

Ryan DH, Yockey SR. Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Curr Obes Rep [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Dec 24];6(2):187. Available from: http:///pmc/articles/PMC5497590/.

JM EWG, GA JGBPB. B, JM C, Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet]. 2016 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];4(11):913–21. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27595918/.

Perreault L, Pan Q, Mather KJ, Watson KE, Hamman RF, Kahn SE. Effect of regression from prediabetes to normal glucose regulation on long-term reduction in diabetes risk: results from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Aug 15];379(9833):2243–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22683134/.

Carvajal R, Wadden TA, Tsai AG, Peck K, Moran CH. Managing obesity in primary care practice: a narrative review. Ann N Y Acad Sci [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Aug 15];1281(1):191–206. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23323827/.

Srivastava G, Apovian CM. Current pharmacotherapy for obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Aug 15];14(1):12–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29027993/.

Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, Aminian A, Angrisani L, Cohen RV et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];33(1):3–14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36336720/.

Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Livingston EH, Van Scoyoc L, Yancy WS et al. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA [Internet]. 2015 Jan 6 [cited 2023 Aug 15];313(1):62–70. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25562267/.

Arterburn DE, Courcoulas AP. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic conditions in adults. BMJ [Internet]. 2014 Aug 27 [cited 2023 Aug 15];349. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25164369/.

Rurik I, Torzsa P, Ilyés I, Szigethy E, Halmy E, Iski G et al. Primary care obesity management in Hungary: evaluation of the knowledge, practice and attitudes of family physicians. BMC Fam Pract [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Aug 15];14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24138355/.

Rubino F, Logue J, Bøgelund M, Madsen ME, Cancino AP, Høy M et al. Attitudes about the treatment of obesity among healthcare providers involved in the care of obesity-related diseases: A survey across medical specialties in multiple European countries. Obes Sci Pract [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];7(6):659–68. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34877005/.

Dewhurst A, Peters S, Devereux-Fitzgerald A, Hart J. Physicians’ views and experiences of discussing weight management within routine clinical consultations: A thematic synthesis. Patient Educ Couns [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];100(5):897–908. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28089308/.

Fogelman Y, Vinker S, Lachter J, Biderman A, Itzhak B, Kitai E. Managing obesity: a survey of attitudes and practices among Israeli primary care physicians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2023 Aug 15];26(10):1393–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12355337/.

Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, Wu Q, Du Y, Gurbuz S et al. Triple-Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity - A Phase 2 Trial. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2023 Aug 10 [cited 2023 Aug 31];389(6). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37366315/.

Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2022 Jul 21 [cited 2023 Aug 31];387(3):205–16. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

Burris JL, Borger TN, Baker TB, Bernstein SL, Ostroff JS, Rigotti NA et al. Proposing a Model of Proactive Outreach to Advance Clinical Research and Care Delivery for Patients Who Use Tobacco. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Dec 24];37(10):2548–52. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35474504/.

Glauser TA, Roepke N, Stevenin B, Dubois AM, Ahn SM. Physician knowledge about and perceptions of obesity management. Obes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2015 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];9(6):573–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25791741/.

Carrasco D, Thulesius H, Jakobsson U, Memarian E. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes about obesity, adherence to treatment guidelines and association with confidence to treat obesity: a Swedish survey study. BMC primary care [Internet]. 2022 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];23(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35971075/.

Petrin C, Kahan S, Turner M, Gallagher C, Dietz WH. Current attitudes and practices of obesity counselling by health care providers. Obes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];11(3):352–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27569863/.

Rathomi HS, Dale T, Mavaddat N, Thompson SC. General Practitioners’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Advice for Weight Control in Their Overweight Patients: A Scoping Review. Nutrients [Internet]. 2023 Jun 27 [cited 2023 Aug 15];15(13):2920. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37447247/.

Bessesen DH, Van Gaal LF. Progress and challenges in anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];6(3):237–48. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28919062/.

McGlone ER, Wingfield LR, Munasinghe A, Batterham RL, Reddy M, Khan OA. A pilot study of primary care physicians’ attitude to weight loss surgery in England: are the young more prejudiced? Surg Obes Relat Dis [Internet]. 2018 Mar 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];14(3):376–80. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29254687/.

Croghan IT, Ebbert JO, Njeru JW, Rajjo TI, Lynch BA, DeJesus RS et al. Identifying Opportunities for Advancing Weight Management in Primary Care. J Prim Care Community Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 15];10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31496342/.

Campbell-Scherer D, Sharma AM. Improving Obesity Prevention and Management in Primary Care in Canada. Curr Obes Rep [Internet]. 2016 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Aug 15];5(3):327–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27342445/.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev [Internet]. 2015 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Dec 24];16(4):319–26. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25752756/.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study had no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KOU and IY conceptualized the study, LA and KOU prepared the protocol, LA carried out the statistical analysis, IY and RP supervised the study, LA, KOU, and BC wrote the original manuscript, IY, and RP were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical committee of MHS (0064-21-MHS). Informed consent was granted by submission of a completed questionnaire. All methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Or Unger Freinkel, K., Yehoshua, I., Cohen, B. et al. Attitudes and knowledge about weight management among primary care physicians in Israel: a cross-sectional study. BMC Prim. Care 25, 92 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02324-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02324-5