Abstract

Background

A high number of drug-related problems has previously been shown among community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare in Skåne County, Sweden. Medication reviews are one way to solve these problems, but their impact is largely dependent on the process. We aimed to evaluate medication reviews for community-dwelling patients regarding the clinical relevance of the pharmacists’ recommendations, and their implementation by general practitioners. We also wanted to investigate if the general practitioners’ tendency to act on drug-related problems was correlated to different factors of the process.

Methods

This was a cohort study, where patients in primary healthcare considered in need of a medication review were selected. Pharmacists identified drug-related problems and gave written recommendations on how to solve the problems to the general practitioner, via the medical record, and in addition in some cases via verbal communication. The clinical relevance of the recommendations was graded according to the Hatoum scale, ranging from one (adverse significance) to six (extremely significant). Descriptive statistics were used regarding the clinical relevance and the general practitioners´ tendency to act on drug-related problems. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between the tendency to act and different factors of the process.

Results

A total of 96.1% of the 384 assessed recommendations from the pharmacists were graded as significant or more for the patient (Hatoum grade 3 or higher). The general practitioners acted on 63.8% of the drug-related problems. Fewer recommendations per patient, as well as verbal communication in addition to written contact, significantly increased the general practitioners’ tendency to act on a drug-related problem. No significant association was seen between the tendency to act and the clinical relevance of the recommendation.

Conclusions

The high proportion of clinically relevant recommendations from the pharmacists in this study strengthens medication reviews as an important tool for reducing drug-related problems. Verbal communication between the pharmacist and the general practitioner is important for measures to be taken. Multiple recommendations for the same patient reduced their likelihood to of being addressed by the general practitioner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The treatment of elderly people is, in many cases a challenge, due to polypharmacy that often comes along with multiple chronic diseases [1]. Besides costs for unplanned hospitalization, drug-related problems (DRPs) often lead to inconveniences for the patient [2]. Many times, DRPs can be avoided by adjusting the treatment based on the individual patient´s unique conditions, benefits, and risks. Medication reviews (MRs) can contribute to the effort to prevent and reduce DRPs [3, 4].

In Skåne County in the south of Sweden, MRs are primarily conducted for hospitalized patients and for patients living in nursing homes. The MRs in nursing homes follow an elaborated structure with pharmacists, physicians and nurses cooperating with the process [5,6,7,8,9].The nurse documents the patient’s symptoms according to a validated assessment tool. The pharmacist identifies potential DRPs and gives suggestions to the physician on how to solve them. A subsequent team discussion supports the physician’s decision-making. The aim is to achieve higher quality and safety in the patient’s medication treatment. For community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare, MRs are not as common as in nursing homes but are on the rise. Data concerning MRs for this new target group are relatively scarce from the Nordic countries. International studies exists, but with varying settings and procedures [10,11,12,13]. Our previously published data from community-dwelling patients [14] showed a higher number of DRPs compared to Swedish studies conducted in nursing homes [8, 9], especially cases of renal impairment or polypharmacy. However, the impact of an MR on the quality and safety of a patient’s treatment is largely dependent on the process. It is therefore important to assess the clinical relevance and the implementation of the recommendations given by the pharmacists. This process has not been evaluated previously for community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare.

We aimed to evaluate MRs for community-dwelling patients regarding the clinical relevance of the pharmacists’ recommendations, and the implementation of the recommendations by the general practitioners (GPs). We also wanted to investigate if the GPs’ tendency to act on the DRP was correlated to different factors in the process.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a non-controlled cohort study. GPs and nurses at 14 public primary healthcare centers participated, as well as 15 clinical pharmacists in Skåne County. MRs for community-dwelling patients was conducted as a newly introduced part of routine healthcare. In their daily work the GPs and nurses at the healthcare centers selected community-dwelling patients in need of an MR due to, for example, suspected DRPs. There were no further inclusion criteria regarding for example number of medications. An informed consent was collected from all included patients. A total of 165 MRs were conducted according to the model and 109 patients were included in the study. Patients living in nursing homes, younger than 18 years, or with protected identity were not included. Ethics approval was granted, and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Procedure

The MRs were conducted from the third quarter of 2018 until the fourth quarter of 2020, in the southern part of Skåne County. The MRs were performed according to a version of the Lund Integrated Medicine Management (LIMM). LIMM is originally a structured model for MRs for hospitalized patients, developed in southern Sweden, where pharmacists identify, and within multi-professional teams solve DRPs [5, 6]. The model has been adjusted to suit primary healthcare [9]. The patients answered a symptom scale, PHASE-20 (PHArmacotherapeutical Symptom Evaluation, 20 questions) [15], which was then sent to the clinical pharmacists together with a current medication list. PHASE-20 is a validated assessment tool for identifying symptoms that may be caused by medication treatment. The tool is based on the presence of symptoms from 19 groups, and one additional open question. PHASE-20 is used for MRs in most counties in Sweden. Based on the received PHASE-20, the current medication list and information from the electronic medical record, the clinical pharmacists identified potential DRPs among the patients. In Sweden electronic medical records is used for all patients. The pharmacists compiled the identified DRPs in the electronic medical record, together with recommendations to the GPs on how to solve the DRPs. Two of the clinical pharmacists, with solid experience, who were also part of the research group, categorized the recommendations into ten categories for the analysis. In case of discrepancy or difficulty in the classification, the pharmacists reached consensus through discussion. The categories followed the existing classification from the template in the electronic medical record, with an addition of the category Consider other measure, and consisted of:

-

1)

For information/notification

-

2)

Consider initiation of drug therapy

-

3)

Consider withdrawal of drug therapy

-

4)

Consider reduced dose

-

5)

Consider increased dose

-

6)

Consider dose regimen adjustment

-

7)

Consider change in drug formulation

-

8)

Consider change of drug therapy

-

9)

Consider evaluation of drug therapy

-

10)

Consider other measure

In addition to the compilation in the medical record, the pharmacist and the GP, in some cases, discussed the recommendations by phone or in a digital meeting. The GPs decided on appropriate measures. Further information about the procedure is presented in previously published work [14].

Data collection

The extent of the GPs’ implementation of the pharmacists’ recommendations within two months after receiving the recommendations was retrieved from the electronic medical record. The time limit of two months was chosen according to the process used in previous similar studies [8, 9]. The information was compiled and categorized by one of the researchers according to Implemented/Partly implemented/Planned/Measures other than proposed taken/No action taken. The research group reviewed a number of samples to ensure a rigorous process. Cases where the GP intended to take a proposed measure, but did not due to the patient’s objection, was categorized as No action taken, considering the intention of this study was to assess the actual implementation. If no information could be found in the medical record, the category No action taken was chosen. The categories Implemented, Partly implemented, Planned, and Measures other than proposed taken were also merged and presented as Action taken.

The collected information from the MRs was used to assess the clinical relevance of the recommendations from the pharmacists. The collected data was sent to two physicians, with no clinical connection to the included patients, and with solid competence and experience in medication safety issues i.e., one geriatrician and the other a GP responsible for the area medication safety for the elderly in the county. The physicians assessed the recommendations independently using the Hatoum’s ranking scale [16]. There is no standardized method for this evaluation, but ranking according to Hatoum et al. has previously been applied in a few Swedish studies [17, 18]. The Hatoum’s ranking scale consists of six rating steps, as shown in Table 1.

In cases with different judgments between the two physicians regarding the ranking, in a second step, they reached consensus through discussion.

Data analysis

The number of recommendations per patient was compiled, as was the number of MRs where the pharmacist and the GP had both verbal and written contact, compared to written only. Descriptive analysis was used for the ranking of clinical relevance of the recommendations from the pharmacists. The extent of agreement between the two physicians was measured with weighted Cohen´s kappa. Descriptive statistics were used regarding the GPs’ tendency to act on the recommendations from the pharmacist. Furthermore, logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between the GPs’ tendency to act and the degree of clinical relevance, the number of recommendations per patient, and a verbal contact or not between the pharmacist and the GP about the recommendations in addition to written contact, respectively. In the regression analysis the above-described categories Action taken, and No action taken were used as dependent variables regarding the implementation. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 28. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 109 included patients, a total of 60 (55%) were women and the median age was 79 years with a range of 52–98 years. The median number of medications per patient was 11 (range 5–28). The clinical pharmacists identified 420 potential DRPs among the patients, giving a mean of 3.9 DRPs per patient and a median of 4 DRPs per patient (range 0–13), as shown in our previous study [14]. Based on the identified DRPs, the pharmacists gave 420 recommendations regarding the drug treatment. The most frequent types of recommendations were Consider withdrawal of drug therapy (n = 96, 22.9%), Consider evaluation of drug therapy (n = 66, 15.7%) and Consider reduced dose (n = 57, 13.6%). The mean (SD) number of recommendations per patient was 3.5 (2.7) and the median number was 4 (range 0–12). The pharmacists and the GPs had verbal contact, in addition to written contact only, regarding 49 (45.0%) of the MRs.

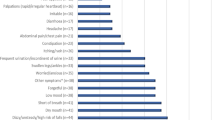

The clinical relevance was ranked for 384 of the recommendations from the pharmacists to the GPs. The category For information/notification was excluded from the ranking, as was recommendations from the pharmacist given directly to the patient. The recommendations directly to the patient could concern, for example, information about compliance or problems regarding the therapy instructions. Of the 384 ranked recommendations, 96.1% were graded as three or higher according to Hatoum’s ranking scale, and 83.1% were graded as four or higher, as shown in Fig. 1. Five of the recommendations (1.3%) were graded as one, Adverse significance. These suggestions were merely recommendations according to clinical guidelines, such as prescribing GLP1-agonist to a frail patient with multimorbidity. The recommendations were however considered not to risk any harm if implemented.

The weighted Cohen’s kappa was 0.63, indicating substantial agreement between the two physicians (Table 2). In 82.3% of the cases, the physicians were in complete agreement. The non-consistent gradings differed by one grade in 65 cases, two grades in two cases, and three grades in just one case. Consensus discussions led to the higher grade in 37 (54.4%) cases.

The GPs acted on 245 (63.8%) of the 384 analyzed recommendations. For 139 recommendations (36.2%), no action was taken. Out of these, information about any action could not be found in the electronic medical record regarding 43 recommendations (11.2%). The distribution into the described categories were: Implemented 163 (42.4%); Partly implemented 20 (5.2%); Planned 34 (8.9%); Measures other than proposed taken 28 (7.3%); No action taken 139 (36.2%).

The results from the multivariable logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 3. The odds for the GPs to act on a DRP, with following recommendation, was 2.4 times higher after written and verbal communication with the pharmacist, compared to written contact only (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.52–3.79 and p-value < 0.001). The odds for the GPs acting on a DRP was 0.58 when the pharmacist gave five or more recommendations/patient, compared to 1–4 recommendations/patient (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.37–0.91 and p-value 0.016). The division into 1–4 and ≥ 5 recommendations/patient was made with regard to equal distribution in the group as well as clinical plausibility. No significant association was seen between the GPs’ tendency to act and the degree of clinical relevance of the recommendation.

Discussion

As much as 96% of the recommendations made by the clinical pharmacists to the GPs regarding identified DRPs were graded to be clinically relevant. The result strengthens MRs as an important tool to reduce DRPs among community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare. The GPs acted on 64% of the DRPs with following recommendations. Fewer recommendations per patient, as well as verbal communication in addition to written contact, increased the GPs’ tendency to act. No correlation was seen between the tendency to act and the degree of clinical relevance of the recommendation.

Given the high clinical relevance of the recommendations from the pharmacists in our study, one may wonder why not more measures were taken. In some cases, there was no sign in the electronic medical record that the GP had read or considered the recommendations, which might have affected the outcome. Possible explanations might be deficiencies in the model, such as lack of time for the GPs to process the information, misunderstanding of the process, need for education, or just a matter of different opinions. Furthermore, the model with MRs for community-dwelling patients was new to the participants, and new processes may need time to implement.

In previous studies, the acceptance rate of pharmacists’ recommendations varied hugely between 30–87%, albeit in different settings [2]. A wide spread of factors is discussed to influence the results/acceptance rate, such as the number of medications, diagnoses, and geographic differences [19,20,21]. One aspect to consider is the clinical reasoning and final assessment of the individual treatment that is made by the GP. The pharmacists highlight changes and evaluations to consider, facilitating the GPs’ decision-making, with the mutual aim of improving quality of treatment and well-being for the patient. Nevertheless, prescribing and deprescribing for elderly patients is a complex process. An acceptance rate of 100% is likely not appropriate to strive for. Furthermore, in some cases, no action was taken due to the patient’s reluctance to change treatment.

We saw no association between the grade of clinical relevance of the pharmacists’ recommendations and whether or not action was taken by the GPs. One reason for this could be that a recommendation with higher clinical relevance might be more challenging to implement. For instance, an adjustment of vitamin B-treatment is easy to apply, but of little importance to the patient, compared to discontinuation of a benzodiazepine, which is more demanding but could increase patient safety. Monzon-Kenneke et al. implied in their work that additional deprescribing would have occurred if the pharmacist was readily available to provide step-by-step instructions [13]. The most frequent type of recommendation from the pharmacists in this study, Consider withdrawal of drug therapy, may thus not always be uncomplicated to manage.

The odds for the GP to act on a DRP were significantly higher after verbal communication with the pharmacist, compared to written contact only. Verbal contact might give an opportunity to discuss details and supplementary questions and is likely to facilitate changes in the treatment regimen. An additional effect is the component of mutual learning among the participants. The results are in accordance with the idea of team-based care and “Good quality, local health care”, promoted by the Swedish government and the National Board of Health and Welfare [22, 23]. Communication is often facilitated through already-established collaborations. In addition, the verbal contact provides a guarantee that the GP becomes aware of the recommendations from the pharmacist, which was not always obvious in this study, based on information collected from the medical record. Some prior Swedish studies with a higher tendency to act (acceptance rate) were performed solely using face-to-face discussions (Lenander 2018; 80%, Bondesson 2012; 90%, compared to 64% in this study) [8, 17]. These previous results strengthen our finding that the tendency to act increases with verbal communication.

Multiple recommendations for the same patient significantly reduced the likelihood of addressment by the GP. The result is of value addressing the further performance of MRs following a similar model. Although each individual recommendation might be clinically relevant, it is important to take patient safety into account and thus not take too many measures at the same time. Elderly patients are often more fragile and changes in treatment must be made with caution [24, 25]. In this study, the patients were living independently and, in many cases, handled their own medications. A GP might be more restrained regarding major adjustments in treatment when the patient has less supervision from healthcare personnel for follow-up. In addition, too many alterations may be confusing for the patient and potentially lead to misunderstandings and new errors. In a nursing home, more structured monitoring is possible, thus making changes easier to implement. Nevertheless, patients living independently are an important target group for MRs, although they may need to be handled more carefully. The results also confirm that it may be wise for pharmacists to limit and prioritize more strictly regarding the number of recommendations.

This study has some limitations. The pharmacists conducting the MRs may have been extra thorough in their work since they knew they were part of a study. This might have led to a higher number of DRPs and following recommendations per MR. However, a vast majority of the recommendations were ranked as significant to the patient, which contradicts the likelihood of this effect. It is also possible that a larger number of included patients may have affected the results regarding possible association between the clinical relevance and the implementation of recommendations. Furthermore, no additional variables were used in the regression analysis such as patient or physician characteristics. Another weakness is the variation of documentation by the GPs in the medical record, which means that information on possibly implemented measures could not always be found. Nor could the GPs’ reasons for not acting on a DRP be retrieved or evaluated. In a future study, it may be interesting to explore the GPs’ decision-making process. A strength of this study is that, to our knowledge, it is the first to evaluate the process of MRs for community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare in terms of clinical relevance of recommendations and different aspects affecting implementation. The use of trained clinical pharmacists, and a well-established model for the MRs (a modified version of LIMM), ensures the consistency and reproducibility of the work. Another strength is that one of the two physicians conducting the ranking of the pharmacists’ recommendations was an experienced physician brought in from outside the research group, to enable independent estimates and ensure that assessment bias was not at risk. In future studies, it would be interesting to evaluate the clinical impact of the MRs for community-dwelling patients on hard endpoints such as hospital admissions, falls or quality of life-measures.

Conclusions

The high proportion of clinically relevant recommendations from pharmacists emphasizes the importance of MRs to avoid DRPs among community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare. The odds for the GP to act on a DRP were significantly higher after verbal communication between the GP and the pharmacist, and with fewer recommendations per patient. This is important knowledge to incorporate when planning for the implementation of MRs for community-dwelling patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DRP:

-

Drug-Related Problem

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- LIMM:

-

Lund Integrated Medicines Management

- MR:

-

Medication Review

- PHASE-20:

-

PHArmacotherapeutical Symptom Evaluation, 20 questions

References

Shah BM, Hajjar ER. Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):173–86.

Placido AI, Herdeiro MT, Morgado M, et al. Drug-related problems in home-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2020;42(4):559–72 (e14).

Gudi SK, Kashyap A, Chhabra M, et al. Impact of pharmacist-led home medicines review services on drug-related problems among the elderly population: a systematic review. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019020.

NICE Medicines and Prescribing Centre. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes Manchester, United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. ; 2015 . Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5. Cited 2022 april 26.

Bergkvist A, Midlov P, Hoglund P, et al. A multi-intervention approach on drug therapy can lead to a more appropriate drug use in the elderly. LIMM-Landskrona Integrated Medicines Management. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):660–7.

Bergkvist Christensen A, Holmbjer L, Midlöv P, et al. The process of identifying, solving and preventing drug related problems in the LIMM-study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(6):1010–8.

Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division; 1998. xiv, 359 pp.

Lenander C, Bondesson A, Viberg N, et al. Effects of medication reviews on use of potentially inappropriate medications in elderly patients; a cross-sectional study in Swedish primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):616.

Milos V, Rekman E, Bondesson A, et al. Improving the quality of pharmacotherapy in elderly primary care patients through medication reviews: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(4):235–46.

Al-Diery T, Freeman H, Page AT, et al. What types of information do pharmacists include in comprehensive medication management review reports? A qualitative content analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45(3):712–21.

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: an overview of systematic reviews. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):661–85.

Kovacevic SV, Miljkovic B, Culafic M, et al. Evaluation of drug-related problems in older polypharmacy primary care patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(4):860–5.

Monzon-Kenneke M, Chiang P, Yao NA, et al. Pharmacist medication review: an integrated team approach to serve home-based primary care patients. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0252151.

Wickman K, Dobszai A, Modig S, et al. Pharmacist-led medication reviews in primary healthcare for adult community-dwelling patients - a descriptive study charting a new target group. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):237.

Hedstrom M, Lidstrom B, Asberg KH. PHASE-20: a new instrument for assessment of possible therapeutic drug-related symptoms among elderly in nursing homes/PHASE-20: ett nytt instrument for skattning av mojliga lakemedelsrelaterade symtom hos aldre personer i aldreboende. Nurs Sci Res Nordic Ctries. 2009;29(4):9–15.

Hatoum HT, Hutchinson RA, Witte KW, et al. Evaluation of the contribution of clinical pharmacists: inpatient care and cost reduction. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1988;22(3):252–9.

Bondesson A, Holmdahl L, Midlöv P, et al. Acceptance and importance of clinical pharmacists’ LIMM-based recommendations. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(2):272–6.

Modig S, Holmdahl L, Bondesson A. Medication reviews in primary care in Sweden: importance of clinical pharmacists’ recommendations on drug-related problems. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(1):41–5.

Benson H, Lucas C, Kmet W, et al. Pharmacists in general practice: a focus on drug-related problems. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(3):566–72.

Stuhec M, Gorenc K, Zelko E. Evaluation of a collaborative care approach between general practitioners and clinical pharmacists in primary care community settings in elderly patients on polypharmacy in Slovenia: a cohort retrospective study reveals positive evidence for implementation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):118.

Zaal RJ, den Haak EW, Andrinopoulou ER, et al. Physicians’ acceptance of pharmacists’ interventions in daily hospital practice. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(1):141–9.

Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Good quality, local health care. A reform for a sustainable health care system (SOU 2020:19). In: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, editor. Stockholm: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; 2020.

Swedish National board of Health and Welfare. National Action Plan for increased patient safety in Swedish Health Care 2020–2024 (socialstyrelsen.se) Stockholm. National board of Health and Welfare,; 2020.

Lavan AH, Gallagher PF, O’Mahony D. Methods to reduce prescribing errors in elderly patients with multimorbidity. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:857–66.

Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. [Indikatorer for god lakemedelsterapi hos aldre] 2017-6-7. 2017-6-7 ed. Stockholm2017.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the pharmacists performing the MRs, and the County Council in Region Skåne for providing financial and administrative support to this study. We wish to thank Anton Grundberg for his expertise in statistical analysis, and Patrick Reilly for valuable advice in reviewing the English language. We are also grateful to Krzysztof Grodon for the evaluation of clinical relevance, and to Sandra Jester-Broms for contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. The study was funded by The Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship, Research and Charity, Lions Research Foundation, Skåne County and the Primary Care Research and Development in the County of Skåne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD designed the study with aid from SM, CL, and BBB. AD and KW collected the data and AD performed the analyses with guidance from SM, CL, and BBB. AD drafted the manuscript with support from SM, CL, and BBB. All authors made contributions to the manuscript and its conclusions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript..

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Swedish Central Ethical Review Board (CEPN) approved the study 2020–07-03; registration number 2020–01517. Informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the study design approved by CEPN, and the Declarations of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dobszai, A., Lenander, C., Borgström Bolmsjö, B. et al. Clinical impact of medication reviews for community-dwelling patients in primary healthcare. BMC Prim. Care 24, 259 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02216-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02216-0