Abstract

Background

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is an emerging cause of visual impairment and blindness and is often detected in the irreversible stage. General practitioners (GPs) play an essential role in the prevention of DR through diabetes control, early detection of retinal changes, and timely referral to ophthalmologists. This study aimed to determine the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards DR screening among GPs in the district primary health centres (PHCs) in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted between April 2021 and February 2022 in 17 randomly selected district PHCs. A validated online questionnaire was then distributed. Good knowledge was defined when the correct response rate was > 75%, positive attitude was indicated when desired attitudes were found in more than half of the items (> 50%), and good practice was defined when more than half of the practice items (> 50%) were performed.

Results

A total of 92 GPs, with a response rate of 60.1%, completed the questionnaire. Seventy-nine respondents (85.9%) were female with a median (range) age of 32 (24–58) years. Among the respondents, 82 (89.1%) had good knowledge and all showed positive attitude on DR screening. However, only four (4.3%) demonstrated good practices. We found a weak positive correlation (rs = 0.298, p = 0.004) between attitude and practices.

Conclusion

GPs in Jakarta showed good knowledge and positive attitude on DR screening. However, they did not show good practice. There was a positive correlation between attitude and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major public health problem in Indonesia. [1] According to the International Diabetes Federation, Indonesia ranks fifth globally in terms of the highest number of people with diabetes (PwD) and this number will increase from 19.5 million to 28.6 million in 2045. [2].

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the leading causes of visual impairment and blindness among the working age population globally. [3] As the global prevalence of diabetes increases, the prevalence of DR and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) are also estimated to increase. [4] A population-based study reported that the prevalence of DR and VTDR were 43.1% and 26.3%, respectively, among Indonesian adults with type 2 DM in the urban and rural areas. [5] Approximately one in four adults with diabetes had VTDR, and 1 in 12 of those with VTDR was bilaterally blind, suggesting the need for effective screening and management of DR. [5].

Timely detection and management of DR could prevent more than 90% of diabetes-related vision loss. [6] The asymptomatic nature of DR and absence of DR screening practice may lead to delays in diagnosis and management. [7] Sasongko et al. reported that 94.9% of PwD in a rural area in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, had not undergone eye examination. [8] Another study showed that a low referral rate accounts for late presentation to ophthalmologists. [9] This underscores the importance of implementing DR screening at the primary care level. In Indonesia, general practitioners (GPs) are the only health professionals who are competent in performing fundus examinations at the primary care level.

In Jakarta, 84.7% of PwD had not undergone eye examination in the past year, and less than half (49.4%) of all patients were told of the need for it. [10] This finding is a major concern because Jakarta is the capital city of Indonesia, with an urban population that continues to increase every year along with increasing economic growth. In Indonesia, primary health centres (PHCs) are government-mandated health clinics at the primary care level. By 2020, there were 340 PHCs in Jakarta, consisting of 44 district health centres and 296 subdistrict health centres. [11] A few services are available at PHCs that provide care for PwD, namely, non-communicable disease clinics, elderly health clinics, and general clinics. [11].

Several studies assessed GPs’ knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards DR in other countries. [12,13,14,15] However, data of KAP towards DR screening among GPs in Indonesia are limited, with only one study conducted in Bandung. [16] This study aimed to determine the KAP level towards DR screening among GPs as well as barriers that may hinder screening at PHCs in Jakarta.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2021 to February 2022 alongside our main research project, which studied DR prevalence in Jakarta by collecting data from 17 district PHCs. Seventeen of 44 district PHCs were selected based on proportional multistage random sampling in each administrative city in Jakarta. District PHCs were preferred because diabetes services are mainly conducted in this area. We distributed a questionnaire through one person-in-charge at each PHC to all 153 GPs in these PHCs.

The sample size for correlation study was calculated with a 95% confidence level, 5% type I and type II errors. Expected correlation was set at 0.5. [16] The final minimum sample size was 46. We included all GPs who worked at the selected PHCs and agreed to complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criterion for this study was incomplete responses.

Questionnaire

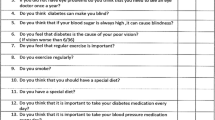

The online questionnaire used in this study was adapted from a previous study that had been validated for the Indonesian population (Supplementary File 1). [16] The KAP questionnaire comprised closed-ended questions consisting of four sections: demographic characteristics, DR-related knowledge, attitude of GPs towards DR screening, and evaluation of practice and barriers in performing DR screening. The last section was an open-ended question that allowed respondents to list the perceived barriers to DR screening.

Scoring

The knowledge section of the questionnaire consisted of 36 questions, of which 10 questions allowed multiple answers. One point was awarded for a correct response, and 0 points were given for incorrect responses. The maximum score on the knowledge section was 36. The sum of all answers to knowledge-related questions was further graded as follows: good, if the score was > 75% or > 27 correct responses; fair, if the score was between 50% and 75% or 18–27 correct responses; and poor, if the score was < 50% or < 18 correct responses.

The attitude section comprised eight questions using the 5-point Likert scale, which had five possible responses: strongly agree, agree, uncertain, disagree, and strongly disagree. Five points were awarded for the most favourable response, and one point was given for the least favourable response. The maximum score for the attitude section was 40. Attitude was considered positive if the score was ≥ 50% or there were at least 20 favourable responses, and a score of < 50% or < 20 favourable responses were categorised as negative attitude.

The practice section of the questionnaire consisted of six questions, with one point awarded for each item that was performed. Practices were categorised as good practice if the score was ≥ 50% or more than three practice items were performed and poor practice if the score was < 50% or less than three practice items were performed. The maximum score for the practice section was 6. The summary of the scoring system for KAP is presented in Table 1.

For perceived barriers, we pooled all barriers, grouped them under similar categories, and calculated the frequency of each category. The barriers categories are as follows: “lack of facilities”, “knowledge- and skill-related factors”, “patient-related barriers”, “time constraint”, “lack of human resources”, “lack of fundoscopy training”, “referral limitation”, and “believe it was not part of primary health care”.

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and recorded on a spreadsheet. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages.

This study also conducted a correlation analysis to determine the relationship between the KAP. Furthermore, we performed a Kurtosis and Skewness analysis followed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to assess the normality assumption of the collected data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test demonstrated the following results: knowledge, p = 0.000 (p < 0.05); attitude, p = 0.200 (p > 0.05); and practice, p = 0.000 (p < 0.05). Of the three variables, only “attitude” was normally distributed. Therefore, we performed the non-parametric Spearman correlation test to identify the correlation between knowledge and attitude, knowledge and practice, and attitude and practice. A p-value of < 0.05 identified through two-tailed tests was considered to be statistically significant. The Guilford criteria were used for the strength of the following: 0.0 to < 0.2, very weak; 0.2 to < 0.4, weak; 0.4 to < 0.7, moderate; 0.7 to < 0.9, strong; and 0.9–1.0, very strong. [17] A p-value of < 0.05 meant that there was a significant correlation between the two variables tested.

Ethical consideration

This study adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical clearance was obtained from the Universitas Indonesia Ethical Review Board (KET-1418/UN.2F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020) on 30 November 2020. Informed consent was obtained on the first page by answering a yes-or-no question before proceeding to the next page containing the survey.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 92/153 GPs completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 60.1%. Most of them were females (79/92, 85.9%), with a median (range) age of 32 (24–58) years. More than half of the respondents (50/92, 53.8%) were between the ages of 30 and 35 years, and 52/92 (56.5%) had 1–5 years of experience in practice, as shown in Table 2.

An overview of the KAP scores is presented in Table 3. This study indicates that 82/92 (89.1%) of GPs in Jakarta had a good level of knowledge and positive attitude. However, only 4/92 (4.3%) were classified as having a good level of DR screening practice.

Table 4 shows the distribution of answers to each item assessing knowledge. Most participants had poor knowledge about DR detection in type 1 DM (T1DM) with only (14/92, 15.0%) correct responses. Correct responses were the highest in items about the prevention of DR complications (87/92, 94.6%).

The responses to statements about attitudes towards performing eye examinations, referral to an ophthalmologist, and early detection of DR in PwD are presented in Table 5. The majority of GPs agreed that all PwD should undergo regular eye examinations despite good glycaemic control (88/92, 95.7%) and should be referred to ophthalmologists (75/92, 81.5%). Most GPs disagreed that eye examination should be performed only in the presence of symptoms (80/92, 87.0%) and that direct fundoscopic examination using direct ophthalmoscopy should be performed by an ophthalmologist only (56/92, 60.8%). Most respondents (90/92, 97.9%) agreed that blindness due to DR could be prevented with early treatment of diabetes and that non-ophthalmologists could help detect DR (74/92, 80.5%). Most GPs (60/92, 65.2%) felt that they were adequately trained in managing patients with eye complaints.

Fifty-two (52/92, 56.5%) GPs conducted visual acuity examination, and twelve (12/92, 13%) GPs had access to an ophthalmoscope at their workplaces. However, fundus examination was performed by only 3/92 (3.3%) GPs in PwD. Thirteen (13/92, 14.1%) GPs had attempted to perform fundus examination in the past 6 months. Sixty-five GPs (65/92, 70.7%) referred PwD to ophthalmologists for eye examinations. Only ten (10/92, 10.9%) GPs attended seminars or training on DM and DR in the past year, as shown in Table 6.

The perceived barriers to DR screening are shown in Fig. 1. Lack of facilities (56/92, 61%), such as ophthalmoscopes, mydriatic eye drops, proper rooms for eye examinations, and portable fundus cameras, was the main barrier, followed by knowledge and skill-related factors (21/92, 23%). Furthermore, (17/92, 18%) GPs perceived 18% of the barriers to be patient-related, such as unawareness of the asymptomatic nature of DR, lack of compliance, lack of understanding of annual DR screening, lack of assistance, and poor family support.

The correlations between the KAP were evaluated using the Spearman correlation analysis (Table 7). There was a significant yet weak positive correlation between attitude and practice (rs = 0.298, p = 0.004).

Sig (two-tailed) * marks indicate a very highly significant correlation, p < 0.05.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study examined the levels and determinants of KAP towards DR screening among GPs at district PHCs, which are government-mandated health clinics in Jakarta. We recruited respondents during our main research project that studied DR prevalence in Jakarta. Our findings indicate that a large percentage of GP had good knowledge of DR, positive attitude, but poor practices.

This study revealed good knowledge regarding DR screening among GPs. Almost all GPs (94.6%) knew about the prevention of DR, similar to the findings reported by Edwiza et al. [16] in Bandung, Indonesia (97.5%), and Al Ghamdi et al. [12] in Taif, Saudi Arabia (92.8%). Since 2020, DM management and its complications have been a priority in Jakarta. Hence, many webinars and training opportunities have been held to increase the awareness of DM and DR among GPs before our data collection.

One most incorrectly answered question was about the recommended initial DR screening following T1DM diagnosis. This is in line with the findings of a study conducted in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. [13] This discrepancy suggests that there was a lower level of comprehension of T1DM screening recommendation, which may be associated with their lower prevalence in Indonesia and the fact that most patients with T1DM are under direct care by endocrinologists in tertiary healthcare. [13].

All GPs demonstrated positive attitudes towards DR screening. The majority (87%) disagreed that eye examination is only needed when vision is affected, and 80.5% agreed that fundoscopic examination by non-ophthalmologists can help reduce vision problems due to diabetes. The studies conducted in Sudan and Nepal have reported similar findings. [14, 15]

Despite their good level of knowledge and attitude, GPs showed poor practice in DR screening. This discrepancy was also reported in previous studies. [12] Poor practice was related to fundus examination and ophthalmoscope access, which are in alignment with studies in Sudan and Bandung, Indonesia. Although a direct ophthalmoscope is a standard instrument in PHCs, it is still not widely available, thus hindering GPs from performing their duties. Nevertheless, similar to the findings in a previous study, GPs tend to refer patients to ophthalmologists for examination. [14, 16] A qualitative study highlighted that GPs faced role confusions in DR screening as some GPs considered themselves as referral source. [6] If every individual with diabetes is referred to ophthalmologists for examination, this will increase the burden on ophthalmologists and the healthcare system. Consequently, patients may be discouraged from visiting ophthalmologists for reasons because of the high number of patients in secondary and tertiary hospitals, fees incurred for travel, and the distant feeling being cared by doctors other than their GPs. Therefore, referral adherence still varies, ranging from 29.9–91.9%.[18,19,20]

Barriers to DR screening vary according to the country’s income level and various system factors in each setting. Different economic and socio-cultural factors would affect the implementation. [21] Management of DR in low-middle income countries faces major challenges due to lack of access to ophthalmologists, healthcare resources, and facilities. [22] The main barrier reported in this study was lack of facilities, such as ophthalmoscopes, mydriatic eye drops, and proper rooms for eye examinations.

GPs’ lack of experience and confidence in performing fundus examinations and diagnosing fundus abnormalities have also been highlighted in other studies. [6, 12, 15] This is coupled with the fact that only 10.9% of respondents had training in eye examinations in patients with diabetes in the past year. PHCs and GPs should be equipped to detect DR as it is a part of GPs’ competence, and the spirit of continuing medical education should be encouraged.

In urban areas, such as Jakarta, implementing a DR screening model using a fundus camera integrated with telemedicine and automated grading by artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising solution. Currently, fundus cameras are the standard equipment, and automated grading by AI has demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy for screening. With this model, DR screening coverage may improve.

Our study found that a significant percentage of respondents referred patients for ophthalmic examination and admitted that they did not try to perform it themselves. A few respondents believed that GPs’ roles did not include DR screening. A study in Australia reported that GPs assumed that ophthalmologists were more suited to perform the task. [6] Efforts should be made to clarify the roles of GPs in diabetes management, including screening for possible complications without delaying referral to ophthalmologists once it is appropriate. Evidence suggests that one of the strategies is a shift in focus on upstream primary approaches targeted at population and community, by promoting a healthier lifestyle and self-management of diabetes and providing equal and wider access to DR screening. [23].

In this study, GPs perceived 18% of the barriers to be patient-related. These included reluctance to referral, low levels of compliance, and socioeconomic problems. If GPs are able to counsel patients and persuade them to cooperate in undergoing annual DR screening and timely management of DR, these issues may be diminished. [24].

We found a positive correlation between attitude and practice of GPs regarding DR screening, which is in contrast to a study reported from a similar setting in Bandung, Indonesia, that showed no significant correlation between attitude and GPs’ practice. [16] In parallel with the study in Taif, Saudi Arabia, no correlation was found between knowledge and practice. [12] Whether existing barriers had interfered with the implementation of knowledge of our respondents is beyond the scope of this study.

One of the limitations of this study is that we were unable to guarantee honest responses, which may have impacted the results.

This study adds to the currently limited body of research on KAP towards DR screening among GPs in Indonesia. Good practices of DR screening among GPs, even in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, still need to be developed. The procurement of ophthalmoscopes or other screening modalities in PHCs and training opportunities are recommended to improve the capacity of GPs in DR screening.

Conclusion

Despite the favourable levels of knowledge and attitude, practice towards DR screening is still poor. Infrastructure and human resources are major factors that should be improved so that DR screening could be part of the management of patients with diabetes in PHCs.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during this study are available upon reasonable request by emailing the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- DM:

-

Diabetes Mellitus

- DR:

-

Diabetic Retinopathy

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- KAP:

-

Knowledge, Attitude, Practice

- PHC:

-

Primary Health Centre(s)

- VTDR:

-

Vision-threatening Diabetic Retinopathy

References

Mihardja L, Manz HS, Ghani L, Soegondo S. Prevalence and determinants of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in Indonesia (a part of basic health research/Riskesdas). Acta Med Indones. 2009;41:169–74.

Aguiree F, Brown A, Cho NH, Dahlquist G, Dodd S, Dunning T et al. IDF diabetes atlas2013.

World Health Organization. Strengthening diagnosis and treatment of diabetic retinopathy in the South-East Asia region 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1302407/retrieve. Accessed 7 December 2021.

Raman R, Gella L, Srinivasan S, Sharma T. Diabetic retinopathy: an epidemic at home and around the world. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:69–75. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.178150.

Sasongko MB, Widyaputri F, Agni AN, Wardhana FS, Kotha S, Gupta P, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and blindness in indonesian adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;181:79–87.

Watson MJ, McCluskey PJ, Grigg JR, Kanagasingam Y, Daire J, Estai M. Barriers and facilitators to diabetic retinopathy screening within australian primary care. BMC Fam Prac. 2021;22:1–10.

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Diabetic retinopathy preferred practice pattern 2019. https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp. Accessed 7 December 2021.

Sasongko MB, Wardhana FS, Febryanto GA, Agni AN, Supanji S, Indrayanti SR, et al. The estimated healthcare cost of diabetic retinopathy in Indonesia and its projection for 2025. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:487–92.

Singh B, Kaur P, Singh J, Grang P. Prevalence and associated risk factors for diabetic retinopathy at first ophthalmological contact. Asian J Med Sci. 2021;12:118–24.

Adriono G, Wang D, Octavianus C, Congdon N. Use of eye care services among diabetic patients in urban Indonesia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:930–5.

Dinas Kesehatan DKI, Jakarta. Profil kesehatan provinsi DKI Jakarta tahun 2020 2020. https://dinkes.jakarta.go.id/berita/profil/profil-kesehatan#~:text=2020-,Unduh,-2. Accessed 7 June 2022.

Al Ghamdi A, Rabiu M, Al Qurashi AM, Al Zaydi M, Al Ghamdi AH, Gumaa SA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice pattern among general health practitioners regarding diabetic retinopathy Taif, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Sci. 2017;6:44.

Alanazi FS, Merghani TH, Alghthy AM, Alyami RH. An assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards diabetic retinopathy among general practitioners of Tabuk City. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2018;73:6655–60.

Elnagieb F, Saleem M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices on diabetic retinopathy among medical residents and general practitioners in Khartoum, Sudan. Albasar Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;4:66.

Pradhan E, Khatri A, Tuladhar J, Shrestha D. Diabetic eye disease related knowledge, attitudes and practices among physicians in Nepal. Jour of Diab and Endo Asssoc of Nepal. 2018;2:26–36.

Edwiza D, Sovani I, Ratnaningsih N, Medissa. Correlation between knowledges and attitudes with the practices of general practitioners regarding diabetic retinopathy in primary health care in Bandung. J Clin Ophthalmol Optom Res. 2021;1:1–7.

Guilford JP. Psychometric methods. Second ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1954.

Mtuya C, Cleland CR, Philippin H, Paulo K, Njau B, Makupa WU, et al. Reasons for poor follow-up of diabetic retinopathy patients after screening in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016;16:1–7.

Zhu X, Xu Y, Lu L, Zou H. Patients’ perspectives on the barriers to referral after telescreening for diabetic retinopathy in communities. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8:e000970.

Stebbins K, Kieltyka S, Chaum E. Follow-up compliance for patients diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy after teleretinal Imaging in primary care. Telemed e-Health. 2021;27:303–7.

Piyasena MMPN, Murthy GVS, Yip JL, Gilbert C, Zuurmond M, Peto T, et al. Systematic review on barriers and enablers for access to diabetic retinopathy screening services in different income settings. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0198979.

Chua J, Lim CXY, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Diabetic retinopathy in the Asia-Pacific. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2018;7:3–16.

Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. The war on diabetic retinopathy: where are we now? Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2019;8:448.

Abu-Amara TB, Al Rashed WA, Khandekar R, Qabha HM, Alosaimi FM, Alshuwayrikh AA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice among non-ophthalmic health care providers regarding eye management of diabetics in private sector of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Endang Sri Wahyuningsih, MD, MKM, and Novita Suprapto Wati, MD, from the DKI Jakarta Provincial Health Office and every person-in-charge from each primary health centre (Puskesmas) for the correspondence and coordination for the diabetic retinopathy screening project and this research. We thank the enumerator team (Fitria Adelita, MD; Anastazia Adeela, MD; and Firlisha Miftanifa Salsabila, SKM) for their contribution in data collection. We thank Nur Afianti Hasanah, SKM, for her guidance in performing the statistical analysis.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D.L, G.A.A., R.S., and R.R. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. R.R. and C.M. acquired the data, prepared tables and figure, and drafted the manuscript. Y.D.L., G.A.A., R.R., C.M., and R.S. analysed, interpreted, reviewed, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Universitas Indonesia Ethical Review Board (KET-1418/UN.2F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2020). Informed consent was obtained on the first page by answering a yes-or-no question before proceeding to the next page containing the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yeni Dwi Lestari is first author. Gitalisa Andayani Adriono, Rizka Ratmilia, Christy Magdalena and Ratna Sitompul are Co-author.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lestari, Y.D., Adriono, G.A., Ratmilia, R. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice pattern towards diabetic retinopathy screening among general practitioners in primary health centres in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. BMC Prim. Care 24, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02068-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02068-8