Abstract

Background

Mounting evidence suggests the safety and efficacy of medical marijuana (MM) in treating chronic ailments, including chronic pain, epilepsy, and anorexia. Despite incremental use of medical and recreational cannabinoids, current limited evidence shows generalized unpreparedness of medical providers to discuss or recommend these substances to their patients. Herein, the present study aims to examine internal medicine residents’ knowledge of marijuana and their attitude towards its medical use.

Methods

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study. A survey with 12 standardized queries was created and distributed among the internal medicine residents from Mount Sinai Morningside-West (MSMW) program from July 2020 to December 2020. Participants included preliminary and categorical residents from post-graduate years one to three. The survey consisted of self-assessment of residents’ knowledge on the indication, contraindication, adverse effects of MM.

Results

Eighty-six (59%) out of 145 residents completed the questionnaire. Despite most trainees (70%) having considered certifying the use of MM for their patients, over 90% reported none to little knowledge on its use. Approximately 80% of the surveyed residents expressed willingness to receive an appropriate educational curriculum.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that indicated a critical lack of medical marijuana-related knowledge in surveyed internal medicine residents. In a population with growing cannabis consumption, physician training on the indication, toxicity, and drug interaction of cannabinoids is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Mounting studies suggest the therapeutic efficacy of cannabis and its derivatives, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), in debilitating conditions such as chemotherapy-induced nausea, anorexia, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [1,2,3]. Moreover, amidst the opioid epidemic, the use of MM may offer a new therapeutic pathway for chronic noncancerous and cancer-related pain. Despite incremental use of medical and non-medical cannabinoids, physicians have reported gaps in their knowledge related to these substances [4]. In this study, we examine the knowledge of internal medicine (IM) residents on marijuana and their attitude towards its medical use.

Methods

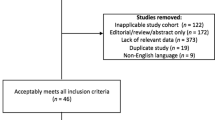

In this descriptive cross-sectional study, IM residents from Mount Sinai Morningside-West (MSMW) program were surveyed from July 2020 to December 2020. The data was collected for a medical education-based needs assessment survey. All trainees from the post-graduate year (PGY) one to three were eligible and included preliminary and categorical residents. An anonymous online questionnaire with 12 standardized queries was created using SurveyMonkey® and distributed via Microsoft® Teams, institutional emails, and smartphone messaging applications. The survey consisted of demographics questions, as well as five-point scale questions about trainees’ self-assessment on MM use, and their stance on MM education during residency training. The full questionnaire is available in Table 1.

MSMW IM residency is an ACGME-accredited program affiliated to Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine (New York City, New York). This is one of the largest academic programs in the United States and is composed of a preliminary internship of 20 trainees and a categorical residency with 125 residents. Approximately 74% of the in-training physicians are international medical graduates.

Results

Eighty-six (59%) out of 145 residents completed the questionnaire, of which 39 (45%) and 47 (55%) were female and male, respectively. 80 (93%) were aged 25 to 34 years. Of participants who chose to disclose their ethnicity, 29 (34%) self-identified as Caucasian, whereas 15 (17%) were Hispanic. PGY-1 trainees had the highest participation rate of 42%, followed by 32% in PGY-2and 26% in PGY-3.

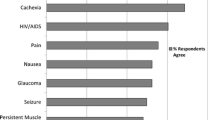

While the majority (n=60, 70%) of trainees had considered certifying medical cannabinoids for their patients, only six (7%) residents felt they had an adequate amount of knowledge (Fig. 1). Regarding indications and contraindications of medical marijuana, almost all residents endorsed having none to some knowledge (respectively n=83 [97%] and n=80 [93%]). Eighty-five (99%) expressed none to some familiarity with marijuana dosing, whereas only four (5%) reported substantial knowledge on different formulations of medical cannabinoid products. Of notable significance, 71 (83%) participants were unsure where to find pertinent information, and 79 (92%) agreed on the necessity of implementing medical education on this substance (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Chronic pain affects 20% of the general population and over 50% of cancer patients. Uncontrolled chronic pain impairs quality of life, exacerbates pre-existing comorbidities, and may lead to depression and anxiety [5, 6]. Opioids remain one of the mainstay treatments for chronic cancer-related pain. Developing opioid tolerance due to chronic use, significant adverse effects, and potential for addiction are deterrent factors that may lead to pain undertreatment in cancer patients [7, 8]. Furthermore, patients with severe chronic pain are at risk of accidental opioid overdose, especially when used concomitantly with benzodiazepines and/or alcohol [9].

Accumulating evidence suggests the safety and efficacy of MM in the treatment of both chronic non-cancerous pain and cancer-related pain. A systematic review with thirty-six trials assessed the efficacy of different MM formulations (sprays, oral, and smoked) to treat non-cancer neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain. In the sixteen evaluable trials, prolonged cannabinoid treatment (two to eight weeks), as opposed to placebo, was associated with a significantly greater reduction in pain (weighted mean difference on a pain visual analog scale was −0.68, 95% confidence interval −0.96 to −0.40, I2 = 8%, P <0.00001) [1]. In patients with advanced cancer with moderate chronic pain, Lichtman et al. observed that administration of nabiximols spray was associated with a median 15.5% improvement in average pain score as opposed to 6.3% with placebo (P=0.0378) [3]. In an observational study, different formulations of THC and CBD (oil, capsules, and cigarettes) were provided to 3,619 patients with severe cancer-related pain (median baseline pain score of 8/10) [2]. In participants who remained on cannabis at six-month follow-up (N=1997, 55%), only 4.6% reported ongoing severe pain. Concomitant opioid use was decreased and stopped respectively in 10 and 36% of patients.

MM showed a positive safety profile in these studies. Treatment-related adverse events were reportedly mild to moderate, and the most common effects were somnolence, dry mouth, increased appetite, dizziness [1,2,3, 10]. Of significant note, fatal overdose secondary to marijuana use is uncommon as opposed to opioids which caused more than 46,000 deaths per year [11]. However, the majority of patients diagnosed with E-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI) have reported use of THC-containing smokeless products [12, 13] and, albeit rare, deaths have been reported [14]. Moreover, there is lacking evidence on long-term effects of cannabinoids.

The United States is experiencing progressive legalization of marijuana for recreational and medicinal purposes. Notwithstanding, limited evidence points to low levels of education on medical cannabis amongst healthcare professionals. In a survey distributed to pharmacy students from six colleges in Ohio, students endorsed low medical marijuana knowledge and felt more education is needed in pharmacy schools [15]. In the same study, medical marijuana education was provided in less than two-thirds of 79 colleges located in MM legal states. In another single-center Spanish study, surveyed nursing students were unaware of indications of medical marijuana. Less than one percent received some type of education regarding cannabis, while more than 85% felt the need to incorporate cannabis education to their curriculum [16]. In another study by Philpot et al., 62 primary healthcare providers in a large healthcare system in Minnesota were surveyed about their attitudes and beliefs about MM. Similar to our findings, their survey concluded that a significant proportion of providers were not comfortable answering patients’ questions about MM, though were willing to receive more related education [4].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to observe a critical lack of knowledge in MM in in-training IM residents. Hence, it is worth implementing a curriculum for resident physicians that includes indications, medication interactions, and side effects of MM use. Questions related to substance use disorder comprised less than two percent in the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification exam [17]. Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program (MKSAP) offered by the American College of Physicians (ACP), a popular study material for ABIM certification exam used by internal medicine residents, does not include any detailed section regarding the indications, contraindications, or adverse effects of cannabinoids [18]. This might lead to a lack of preparedness of residents as frontline providers. Indeed, cannabis use is augmenting due to the increasing number of legalizing states, expansion of its off-label uses, and generalization of recreational uses. Physicians should be familiarized with its use, as well as with the management of MM-related toxicities. At the same time, qualifying conditions for MM use vary depending on the state of practice. Local graduate medical education offices should incorporate pertinent curriculum while keeping up pace with federal and state policy changes.

Our survey results were based on a single-institution experience from an academic center located in New York. A significant percentage of surveyed trainees obtained their medical degrees from outside countries. Nevertheless, the present study emphasizes the lack of formal education on medical cannabis during IM residency training and not before it. Albeit the survey participation was limited, we believe the results were relevant as they show a general trend towards a lack of knowledge on medical cannabis and point to the necessity of a formal educational curriculum.

Limitations

The study is a descriptive cross-sectional study at a single institution and may not be extendible to residencies or IM programs across the country. Additionally, our study seeks the residents to self-rate their knowledge and attitude regarding MM use.

Conclusion

The consumption of medical and nonmedical cannabis is growing. Our study highlighted a needs assessment for MM education at our institution, with the results recognizing the resident's self-awareness about their lack of knowledge. Frontline providers like in-training residents should be familiarized with MM. Analogous studies, if done in other programs across the country, may yield similar results resulting in a more extensive discussion about the need for curriculum development.

Ethical declarations

Our study “Medical Marijuana Knowledge and Attitudes amongst Internal Medicine Residents” did not consist of any experimental protocols. In this descriptive cross-sectional study, IM residents from Mount Sinai Morningside-West (MSMW) program voluntarily responded to the distributed survey. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The IRB determined that the proposed activity is not research involving human subjects as defined by DHHS and FDA regulations. The data set presented is the secondary use of information collected for purposes other than research (medical education-based needs assessment). The holder of any identifiable data would never share those identifiers, nor could data be linked to any identifiable information. For that reason, the Federal Regulations did not apply, including obtaining consent. Accordingly, the IRB determined this project to be Not Human Subjects (NHSR) research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABIM:

-

American Board of Internal Medicine

- ACP:

-

American College of Physicians

- CBD:

-

Cannabidiol

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- IM:

-

Internal medicine

- MKSAP:

-

Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program

- MM:

-

Medical marijuana

- MSMW:

-

Mount Sinai Morningside-West

- PGY:

-

Post-graduate year

- THC:

-

Tetrahydrocannabinol

References

Johal H, et al. Cannabinoids in chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;13:1179544120906461.

Bar-Lev Schleider L, et al. Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:37–43.

Lichtman AH, et al. Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of nabiximols oromucosal spray as an adjunctive therapy in advanced cancer patients with chronic uncontrolled pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(2):179–188 e1.

Philpot LM, Ebbert JO, Hurt RT. A survey of the attitudes, beliefs and knowledge about medical cannabis among primary care providers. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):17.

Marcus DA. Epidemiology of cancer pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(4):231–4.

Sica A, et al. Cancer- and non-cancer related chronic pain: from the physiopathological basics to management. Open Med. 2019;14:761–6.

Hayhurst CJ, Durieux ME. Differential opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a clinical reality. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(2):483–8.

Saha S, Nathani P, Gupta A. Preventing opioid-induced constipation: a teachable moment. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1371–2.

U.S. Surgeon general’s advisory on naloxone and opioid overdose. 2018 [cited 10 Jan 2021]; Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/opioids-and-addiction/naloxone-advisory/index.html.

Anderson SP, et al. Impact of medical cannabis on patient-reported symptoms for patients with cancer enrolled in Minnesota’s Medical Cannabis Program. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(4):e338–45.

Wilson N, et al. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290–7.

Heinzerling A, et al. Severe lung injury associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products-California, 2019. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):861–9.

Schier JG, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use - interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(36):787–90.

Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of E-cigarette, or vaping, products. 2021 [cited 8 Jan 2022]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html#latest-information.

Berlekamp D, et al. Surveys of pharmacy students and pharmacy educators regarding medical marijuana. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2019;11(7):669–77.

Pereira L, et al. Nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding medical marijuana: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7).

Internal medicine certification examination blueprint. 2021 [cited 8 Jan 2022]; Available from: https://www.abim.org/Media/h5whkrfe/internal-medicine.pdf.

MKSAP 19 features. 2019 [cited 8 Jan 2022]; Available from: https://www.acponline.org/featured-products/mksap-19.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Self-funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IM: design of the work, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing and review. BZ: design of the work, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing and review. MK: design of the work, data acquisition and analysis, manuscript writing and review. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Makki, I., Zheng-Lin, B. & Kohli, M. Medical marijuana knowledge and attitudes amongst internal medicine residents. BMC Prim. Care 23, 38 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01651-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01651-9