Abstract

Background

Suggestions of overprescribing of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for long-term treatment in primary care have been raised. This study aims to analyse associations between general practice characteristics and initiating long-term treatment with PPIs.

Methods

A nationwide register-based cohort study of patients over 18 years redeeming first-time prescription for PPI issued by a general practitioner in Denmark in 2011. Patients redeeming more than 60 defined daily doses (DDDs) of PPI within six months were defined first-time long-term users. Detailed information on diagnoses, concomitant drug use and sociodemography of the cohort was extracted. Practice characteristics such as age and gender of the general practitioner (GP), number of GPs, number of patients per GP, geographical location and training practice status were linked to each PPI user. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine associations between practice characteristics and initiating long-term prescribing of PPIs.

Results

We identified 90 556 first-time users of PPI. A total of 30 963 (34.2 %) met criteria for long-term use at six months follow-up. GPs over 65 years had significantly higher odds of long-term prescribing (OR 1.32, CI 1.16-1.50), when compared to younger GPs (<45 years). Furthermore, female GPs were significantly less likely to prescribe long-term treatment with PPIs (OR 0.87, CI 0.81-0.93) compared to male GPs.

Conclusions

Practice characteristics such as GP age and gender could explain some of the observed variation in prescribing patterns for PPIs. This variation may indicate a potential for enhancing rational prescribing of PPIs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

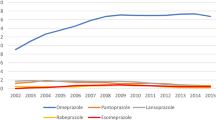

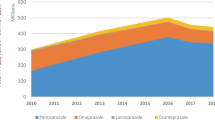

Prescribing of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has increased significantly over the past decades and the vast majority is redeemed in primary care [1]. An increasing number of patients appear to be treated with PPIs for longer periods of time [1], and it has been stated that PPIs are prescribed and continued for questionable reasons [2–4]. Guidelines to promote rational management of patients with dyspepsia and rational prescribing of PPIs have been introduced [5, 6], but do not seem to have influenced the increasing prescribing substantially [1].

Patients are prescribed increasing quantities of PPI on an empirical background when initiating treatment [7]. A few weeks of treatment can cause acid rebound hypersecretion and acid related symptoms after withdrawal [8, 9]. Therefore, prescribing of PPIs for ambiguous reasons for more than a few weeks entails the risk of creating a vicious circle increasing the need for PPIs. Hence, moderation when initiating PPI treatment for unclear reasons is warranted.

Several factors might influence the prescribing pattern of PPIs. It has been demonstrated that patient-related factors have some impact on the prescribing of PPIs [7, 10, 11], but physician-related factors might be of importance as well. Studies have shown that general practice characteristics such as practice size, organisation in partnership or single-handed practices, the degree of urbanisation and having training practice status influence management of patients [12–17]. How general practice factors are associated with initiating long-term treatment with PPIs have not been analysed. Identifying practice characteristics of importance for initiating long-term PPI therapy may have implications for future organisation of primary care services and can help develop targeted interventions to enhance rational prescribing. Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyse associations between practice characteristics and initiation of long-term treatment with PPIs.

Methods

This study is a register-based cohort study of the entire Danish population of approximately 5.6 million people and all general practices in Denmark (approximately 2200 practices [18]). The Danish health care system is tax-funded, and more than 98 % of the inhabitants are registered with a GP, who acts as gatekeeper, performing initial diagnostics and treatment and referring patients to secondary care when required. All citizens have free and equal access to health care services [18].

All inhabitants are assigned a unique civil registration number, and each general practice is registered with their own identification number. These identification numbers enable accurate linkage of patients and general practices through all national registers [19].

Patient cohort sampling

In the Danish National Prescription Register [20] we identified all individuals over 18 years redeeming a prescription for PPI in 2011. The date of the first redemption of PPI in 2011 was defined the index date. In order to include only incident PPI users, patients having redeemed PPIs within six years prior to the index date were excluded. The cohort was followed for six months, and similar to other studies [21, 22], patients redeeming >60 DDDs within six months were defined incident long-term users (Fig. 1). Patient factors in terms of gastrointestinal morbidity [23], use of ulcerogenic medication [23], general comorbidity [10] and socioeconomic status [10, 11] have in previous studies been associated with use of PPIs. Therefore, we retrieved additional data on diagnoses from the Danish National Patient Register [24], the Danish National Prescription Register and data on income, cohabitation status and highest attained education from sociodemographic registers contained in Statistics Denmark [25, 26]. Drugs were defined as comedication, if the patient had redeemed a quantity covering the date of redeeming the PPI. Morbidity was analysed as gastrointestinal morbidity (diagnoses of peptic ulcer, gastrooesophageal reflux disease (including oesophagitis), functional dyspepsia) and as general comorbidity measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index [27].

General practice data

The prescriptions for PPI were linked to the prescriber through the Danish National Health Service Provider Register. We extracted data on the general practices prescribing PPIs to the cohort of first-time users. The average list size of a typical Danish GP is 1600 patients [18], and practices with atypical small list sizes (<500 patients) were excluded, because they were thought not to be representative (Fig. 2). Practices with missing data in 2010 or 2011 were omitted as well, as this indicates that these practices were established or closed in that period (Fig. 2).

We identified the number of doctors registered at each practice and catagorised them as established GPs or temporary doctors. Doctors not registered in the entire period were defined temporary doctors. Practices were defined single-handed practices, if only one established GP was registered, and partnership practice if two or more established GPs were registered. The majority of temporary doctors in general practice are junior doctors having a six- to twelve-month residency, and practices with these doctors listed were defined training practices. We calculated the number of patients per GP by dividing the practice’s patient list size by the number of established GPs within the practice. In single-handed practices the age and gender of the GP were retrieved, and in partnership practices we calculated the mean age of the established group of GPs and assessed, whether the group of established GPs comprised exclusively men or women, predominantly men or women or equally mixed.

The postcode of all practices was extracted. Practices within the greater Copenhagen postcode area were categorised as capital area practices. Practices outside the capital area, but in a postcode comprising a city with more than 10 000 inhabitants, were labelled provincial city practices. All other practice locations were categorised as rural [28]. According to Danish legislation neither the individual GP nor the individual patient should be identifiable for the researchers. Therefore, a few practices (N = 4) with postcode comprising less than three other practices had missing postcode and could not be characterised according to degree of urbanisation.

For each practice we calculated a “long-term user proportion” defined as the proportion of incident users of PPIs within the practice who fulfilled the criteria for long-term use six months after the initial prescription (>60 DDD).

Statistics

The analyses were conducted both with the entire cohort of general practices and with stratification into single-handed and partnership practices. This was done because the variables age and gender were exact values in single-handed practices, but average values in partnership practices. Mixed effects logistic regression models with patients nested within practice were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for associations between long-term prescribing of PPIs and practice characteristics. Two regression models were used. Model one estimated the crude OR for the association of each practice characteristic and prescribing of long-term treatment with PPIs. Model two estimated the OR for each practice characteristic, adjusted for both patient characteristics and other practice characteristics included in the analyses. Patient characteristics adjusted for were age, gender, gastrointestinal morbidity, socioeconomic status (income, highest attained education and cohabitation status), comedication with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and comorbidity [7].

A sensitivity analysis with a definition of long-term use increased to 90 DDDs within six months was performed in order to explore the consistency of the associations when changing threshold for long-term use.

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant associations. All analyses were performed using STATA12 (STATACorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics

According to “The Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects in Denmark” this register-based study did not require approval by the Research Ethics Committee. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency, J. nr. 2012-41-0280. Neither patients nor GPs were identifiable in the dataset.

Results

We identified 124 133 adult first-time users of PPI in 2011. For 90 556 (72.9 %) of the first-time users the prescription for PPI was issued in general practice. Six months after initial redemption of PPIs the cohort was subdivided into short-term and long-term users (Fig. 1). A total of 3475 individuals were lost to follow-up, because they had either died or moved abroad within the six months. Hence, their use of PPI in the observation period could not be assessed and they were excluded. A total of 30 963 (35.5 %) of the 87 081 first-time users starting therapy initiated in general practice and available for follow-up met criteria for long-term use (the “long-term user proportion”) (Fig. 1).

The prescriptions for PPI to the cohort of first-time users derived from 2128 general practices. A total of 65 practices were excluded due to atypical small list size (<500 patients). A total of 144 practices were excluded due to missing data, indicating that they might have been established or closed down in 2010 or 2011 (Fig. 2). Characteristics of the 1919 representative practices initiating PPI therapy were obtained.

The distribution of the “long-term user proportion” among general practices is illustrated in Fig. 3 and demonstrates a large variation among practices in the proportion of patients redeeming more than 60 DDDs of PPI within six months after starting PPI treatment.

Table 1 illustrates the general practice characteristics and the corresponding mean “long-term user proportion”.

When comparing all general practices, univariate regression analyses revealed that initiating long-term treatment with PPIs was significantly associated with GPs being male, 55 years and above, single-handed practice and practicing in rural locations (Table 2).

Only GPs being male and aged 55 years and above were independently and significantly associated with initiating long-term treatment with PPIs in the adjusted analyses (Table 2). These associations remained statistically significant, when stratifying the analyses into single-handed and partnership practices, except for GP age group in single-handed practices where only age of 60 years and above was significantly associated with initiating long-term treatment with PPIs (Tables 3 and 4). Similar associations were found in the sensitivity analysis with the definition of long-term use increased to >90 DDDs within six months, i.e. increasing the threshold for long-term use changed neither the direction nor the magnitude of the associations substantially.

In the stratified analyses, a positive association between training practice status and initiating long-term treatment with PPIs was statistically significant for partnership practices (OR 1.08, CI 1.02-1.14).

Discussion

Main findings

Male gender and increasing age of GPs are significantly associated with initiating long-term treatment with PPIs in a cohort of first-time users treated in a primary care setting. However, general practice characteristics do not seem to be strong predictors of initiating long-term treatment with PPIs as the magnitude of the associations is modest. The apparent variation with regard to rurality and partnership status observed in the crude analyses was no longer statistically significant when adjusting for practice- and patient-related factors. Given that the patient population in rural and single-handed practices is older and has a higher degree of morbidity [29, 30], this might reflect a different composition of patient populations in different practice types and locations.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is the register-based design enabling us to include information on all GPs issuing first-time prescriptions of PPI to a nationwide cohort of incident PPI users. The validity of the register data is considered high [20], and the accurate linkage between the patient-related factors and the practice characteristics makes it possible to adjust for numerous predisposing patient factors and thereby isolate and analyse the independent associations between practice characteristics and initiation of long-term treatment with PPIs. Only 3 % of the total sale of PPI in Denmark is over-the-counter [1], and therefore registration of PPI use is considered almost complete.

The fact that we extracted practice data at the time of initiating long-term treatment with PPIs provides the study with the strength to accurately identify factors of the physician responsible for initiation of long-term prescribing and to characterise practice features as predictors for incident long-term prescribing. In case we had analysed practice characteristics associated with prevalent long-term prescribing of PPIs, we would not have been able to be sure of the validity of the predictors, because prevalent long-term prescribing might have been established several years earlier by another physician.

However, influence of unmeasured factors cannot be ruled out. The linkage between the prescription and the physician factors can only be made at practice level, impeding identification of the GP within partnership practices primarily providing care to the patient. This limitation makes it difficult to assess the effects of doctors’ age and gender in partnership practices. Exact information on age and gender would have been more precise than the mean age of doctors within the practice and the relative gender distribution. Therefore, the associations between long-term prescribing of PPIs and GP age and gender can only be certain for single-handed practices, though the associations seem similar for partnership practices.

Other potential influential variables could have been interesting to include in the analyses had they been available. Practice characteristics such as distance to outpatient clinics (i.e. endoscopy, gastroenterological expertise etc.) could influence prescribing of PPIs. However, data on practice location are limited to postcodes in order to keep the individual prescriber unidentifiable, and the exact address is not available to calculate distance to outpatient clinics.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published studies

To the best of our knowledge no other study has investigated the associations between practice characteristics and prescribing of PPIs. Our study does not clarify why older GPs to a greater extent prescribe long-term treatment with PPIs in first-time users, but it is important to keep in mind that few single-handed practices are run by younger GPs (Table 1). These practices could have a smaller long-term user proportion due to random variation, decreasing the comparability between younger and older GPs in single-handed practices. Nevertheless, in line with our findings it has been demonstrated that older GPs have higher prescribing rates [14, 31, 32] and lower rates of non-pharmacological treatments [14]. Similar to our analyses, other studies have found that GPs of male gender have higher prescribing rates [31, 33]. This could be due to the traditional thought of female GPs being more psychosocially orientated and more patient-centred compared to male GPs [34, 35].

In the multivariate analyses we found no association between single-handed practices and high rate of initiating long-term prescribing of PPIs. In some studies partnership practices have been associated with higher scores for quality of care in chronic diseases [12, 36], although the opposite has been shown as well [37, 38]. Moreover, patient satisfaction seems to be higher in single-handed practices [39]. However, in the present study we cannot determine either quality of care or patient satisfaction.

Being a training practice has also been shown to influence management of patients and quality of care [12, 40]. In our study we saw no association between training practice status and initiating long-term treatment with PPIs except for partnership practices, where training practices had slightly higher odds of initiating long-term treatment (OR 1.08, CI 1.02-1.14). Why training practice status influences partnership practices, but not single-handed practices, is unknown. The association found is, however, fairly weak and just barely statistically significant.

Rurality has been associated with higher rates of inappropriate prescribing [41] and different prescribing patterns [42]. That we do not find similar associations could be due to the fact that Denmark is a quite homogenous country with small distances and less difference between rural and urban areas compared to other countries.

Conclusion

Overall we conclude that there was significant variation in initiating long-term treatment with PPIs between practices. Some of this variation was associated with GP characteristics despite part of the variation being due to differences in characteristics of patient population. This underlines the importance of taking patient characteristics into account, when assessing associations between GP characteristics and prescribing rates.

Whether or not initiating prescribing of long-term treatment with PPIs reflects quality in the clinical setting is challenging to determine in this study, but our results indicate that older GPs and GPs of male gender might have lower threshold for initiating long-term treatment with PPIs, though the associations found were modest. Some of the variation could be due to differences in thoughts and knowledge about PPIs [43, 44]. The demonstration of a variation does not in itself require interventions, but the findings could contribute to evidence-based design of future interventions to enhance rational prescribing of PPIs. The results call for reflection and awareness of the fact that the care delivered is influenced by the health care provider. To fully understand the variations in initiating long-term use of PPIs, future research could benefit from moving beyond the aggregate associations and further explore the mental and social processes at work.

Abbreviations

CI, Confidence interval; DDDs, Defined daily doses; GP, General Practitioner; NSAIDs, Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, Odds ratio; PPIs, Proton pump inhibitors; SSRIs, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

References

Haastrup P, Paulsen MS, Zwisler JE, Begtrup LM, Hansen JM, Rasmussen S, et al. Rapidly increasing prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care despite interventions: A nationwide observational study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(4):290–3.

Van Soest EM, Siersema PD, Dieleman JP, Sturkenboom MC, Kuipers EJ. Persistence and adherence to proton pump inhibitors in daily clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(2):377–85.

van Vliet EP, Otten HJ, Rudolphus A, Knoester PD, Hoogsteden HC, Kuipers EJ, et al. Inappropriate prescription of proton pump inhibitors on two pulmonary medicine wards. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(7):608–12.

Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic effect of overuse of antisecretory therapy in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):e228–34.

Talley NJ, Vakil N. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(10):2324–37.

Dyspepsia and gastro‑oesophageal reflux disease: Investigation and management of dyspepsia, symptoms suggestive of gastro‑oesophageal reflux disease, or both. Cg184. London: National Institute of Clinical Excellence; 2014.

Haastrup PF, Paulsen MS, Christensen RD, Søndergaard J, Jarbøl DE. Medical and non-medical predictors of initiating long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: A nationwide cohort study of first-time users during a 10-year period. Aliment Pharmacol Ther; 2016. doi:10.1111/apt.13649 E-pub ahead of print

Reimer C, Sondergaard B, Hilsted L, Bytzer P. Proton-pump inhibitor therapy induces acid-related symptoms in healthy volunteers after withdrawal of therapy. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1):80–7.

Niklasson A, Lindstrom L, Simren M, Lindberg G, Bjornsson E. Dyspeptic symptom development after discontinuation of a proton pump inhibitor: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(7):1531–7.

van Boxel OS, Hagenaars MP, Smout AJ, Siersema PD. Socio-demographic factors influence chronic proton pump inhibitor use by a large population in the Netherlands. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(5):571–9.

Targownik LE, Metge C, Roos L, Leung S. The prevalence of and the clinical and demographic characteristics associated with high-intensity proton pump inhibitor use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(5):942–50.

Ashworth M, Armstrong D. The relationship between general practice characteristics and quality of care: A national survey of quality indicators used in the UK quality and outcomes framework, 2004-5. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:68.

Nielen MM, Schellevis FG, Verheij RA. Inter-practice variation in diagnosing hypertension and diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:6.

Charles J, Britt H, Valenti L. The independent effect of age of general practitioner on clinical practice. Med J Aust. 2006;185(2):105–9.

Koefoed MM, Sondergaard J, Christensen R, Jarbol DE. General practice variation in spirometry testing among patients receiving first-time prescriptions for medication targeting obstructive lung disease in denmark: A population-based observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:113.

Allenby A, Kinsman L, Tham R, Symons J, Jones M, Campbell S. The quality of cardiovascular disease prevention in rural primary care. Aust J Rural Health. 2016;24:92-8.

Weigel PA, Ullrich F, Shane DM, Mueller KJ. Variation in primary care service patterns by rural-urban location. J Rural Health. 2016;32:196-203.

Pedersen KM, Andersen JS, Sondergaard J. General practice and primary health care in denmark. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25 Suppl 1:S34–8.

Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5.

Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):38–41.

Zwisler JE, Jarbol DE, Lassen AT, Kragstrup J, Thorsgaard N, de Muckadell OB S. Placebo-controlled discontinuation of long-term acid-suppressant therapy: A randomised trial in general practice. Int J Family Med. 2015;2015:175436.

Lodrup A, Reimer C, Bytzer P. Use of antacids, alginates and proton pump inhibitors: A survey of the general danish population using an internet panel. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(9):1044–50.

Lassen A, Hallas J, de Muckadell OB S. Use of anti-secretory medication: A population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(5):577–83.

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3.

Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):103–5.

Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):91–4.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Olsen MH, Boje CR, Kjaer TK, Steding-Jessen M, Johansen C, Overgaard J, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage at diagnosis of head and neck cancer - a nationwide study from dahanca. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):759–66.

Anderson TJ, Saman DM, Lipsky MS, Lutfiyya MN. A cross-sectional study on health differences between rural and non-rural U.S. counties using the county health rankings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):441.

Lutfiyya MN, McCullough JE, Haller IV, Waring SC, Bianco JA, Lipsky MS. Rurality as a root or fundamental social determinant of health. Dis Mon. 2012;58(11):620–8.

Wang KY, Seed P, Schofield P, Ibrahim S, Ashworth M. Which practices are high antibiotic prescribers? A cross-sectional analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(567):e315–20.

Sutton M, McLean G. Determinants of primary medical care quality measured under the new UK contract: Cross sectional study. BMJ. 2006;332(7538):389–90.

Tsimtsiou Z, Ashworth M, Jones R. Variations in anxiolytic and hypnotic prescribing by GPs: A cross-sectional analysis using data from the UK quality and outcomes framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(563):e191–8.

Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: A critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519.

Jefferson L, Bloor K, Birks Y, Hewitt C, Bland M. Effect of physicians’ gender on communication and consultation length: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(4):242–8.

Millett C, Car J, Eldred D, Khunti K, Mainous 3rd AG, Majeed A. Diabetes prevalence, process of care and outcomes in relation to practice size, caseload and deprivation: National cross-sectional study in primary care. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(6):275–83.

Ng CW, Ng KP. Does practice size matter? Review of effects on quality of care in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(614):e604–10.

Saxena S, Car J, Eldred D, Soljak M, Majeed A. Practice size, caseload, deprivation and quality of care of patients with coronary heart disease, hypertension and stroke in primary care: National cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:96.

Heje HN, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Olesen F. Doctor and practice characteristics associated with differences in patient evaluations of general practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:46.

Ashworth M, Schofield P, Seed P, Durbaba S, Kordowicz M, Jones R. Identifying poorly performing general practices in England: A longitudinal study using data from the quality and outcomes framework. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16(1):21–7.

Lund BC, Charlton ME, Steinman MA, Kaboli PJ. Regional differences in prescribing quality among elder veterans and the impact of rural residence. J Rural Health. 2013;29(2):172–9.

McLean G, Guthrie B, Sutton M. Differences in the quality of primary medical care services by remoteness from urban settlements. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(6):446–9.

Wermeling M, Himmel W, Behrens G, Ahrens D. Why do GPs continue inappropriate hospital prescriptions of proton pump inhibitors? A qualitative study. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20(3):174–80.

Grime J, Pollock K, Blenkinsopp A. Proton pump inhibitors: Perspectives of patients and their GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):703–11.

Acknowledgements

We thank Biostatistician Maria Reimert Munch for assistance with the analyses and Lise Keller Stark for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Region of Southern Denmark and University of Southern Denmark. The funding sources did not have any involvement in any parts of the study.

Availability of data and materials

Due to data protection regulations of both the Danish Data Protection, Statistics Denmark and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority the access to data is strictly limited to the researchers who have obtained permission for data processing.

Authors’ contributions

All authors took part in designing the study and interpreting data. Peter Fentz Haastrup drafted the manuscript and the other authors revised it critically. All authors have approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Authors’ information

The author group comprises different areas of expertise relevant to the study. JS and DEJ are general practitioners and JS is a clinical pharmacologist as well. JMH is a medical gastroenterologist with several years of experience with gastroenterological research in primary care.

Competing interests

Jens Søndergaard has been a member of advisory board for Astra Zeneca.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics

According to the Act on a Biomedical Research Ethics Committee System in Denmark and the Processing of Biomedical Research Projects, Part 2 § 2, 1, the project was not a biomedical research project and therefore did not need the ethic committee’s approval (http://www.cvk.sum.dk/English/actonabiomedicalresearch.aspx.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Haastrup, P.F., Rasmussen, S., Hansen, J.M. et al. General practice variation when initiating long-term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 17, 57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0460-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0460-9