Abstract

Background

To investigate the prevalence of protocol registration (or development) among published dose-response meta-analyses (DRMAs), and whether DRMAs with a protocol are better than those not.

Methods

Three databases were searched for eligible DRMAs. The modified AMSTAR (14 items) and PRISMA checklists (26 items) were used to assess the methodological and reporting quality, with each item assigned 1 point if it met the requirement or 0 if not. We matched (1,2) DRMAs with registered or published protocol to those not, by region and publication years. The summarized quality score and compliance rate of each item were compared between the two groups. Multivariable regression was employed to see if protocol registration or development was associated with total quality score.

Results

We included 529 DRMAs, with 45 (8.51%) completed protocol registration or development. We observed a higher methodological score for DRMAs with protocol than the matched controls (9.47 versus 8.58, P < 0.01); this embodied in 4 out of 14 items of AMSTAR [e.g., Duplicate data extraction (rate difference, RD = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.30; P = 0.01). A higher reporting score (cubic transformed) for DRMAs with protocol than the matched controls was also observed (11,875.00 versus 10,229.53, P < 0.01); which embodied in 6 out of 26 items of PRISMA [e.g. Describe methods for publication bias (RD = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.14; P = 0.02)]. Regression analysis suggested positive association between protocol registration or development and total reporting score (P = 0.012) while not for methodological score (P = 0.87).

Conclusions

Only a small proportion of DRMAs completed protocol registration or development, and those with protocol were better reported than those not. Protocol registration or development is highly desirable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses represent the highest level of evidence in the hierarchy of clinical evidence of medicine, and becoming increasingly popular in multiple domains [1,2,3]. Since 1986, over 30,000 systematic reviews and meta-analyses reports have been published, and the number continued to increase rapidly [4]. The extensive growth however partly contributes to overlapping production of systematic reviews and unnecessary duplications [5,6,7]. The quality and value of such works has been questioned by the scientific community for causing confusions and research waste [4, 8].

Great efforts have been expended to solve the problem [9, 10]. One important work is the launch of the international prospective registry platform (PROSPERO, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) of systematic reviews. Since then, a large number (more than 20,000 by 2016) of registrations were recorded and opened to the public [11]. Another important effort was the development of guidelines for systematic reviews, such as the PRISMA and PRISMA-P statements, which provided guidance for the conducting and reporting of systematic reviews and their protocols [10, 12, 13]. The prospective registration or publication of protocol of systematic reviews a priori is expected to be a valid way to reduce aforementioned research waste [14, 15]. This approach ensures a carefully documented plan before the systematic review starts [12, 13] and allows researchers to see which questions were already registered. It may be beneficial to the quality for the further implementation and reporting.

Dose-response meta-analysis (DRMA) is a type of meta-analysis investigating the dose-response relationship between an exposure and outcome of interest [16, 17]. It becomes popular since Greenland and Orsini published the classical generalized least squares for trend method [16, 17]. Given the aforementioned advantages, adherence to the established checklists for registration or development of protocol may play an important role for the quality of DRMA. This is essential that high quality and informative evidence is the foundation for healthcare decision. Nevertheless, no study had ever investigated the influence of this approach on DRMAs.

We conducted a cross-sectional study by collecting published DRMAs to investigate the prevalence of registration or development of protocol, and whether DRMAs with protocol registration or development were better than those not. The significances of current research are: 1) to verify the importance and realistic value of registration of systematic reviews and meta-analyses; 2) to strengthen the awareness of evidence quality for decision makers and guideline developers; 3) to enhance attention of registration for systematic review and meta-analysis authors.

Methods

We constructed our research as the following sections: we first searched the main literature databases for eligible DRMAs; the registration (or protocol) information was extracted and the eligible DRMAs were categorized into those registered (or with a protocol) and those not. A matching procedure was applied for DRMAs with protocol registration or development and those not to balance the baseline characteristics. The methodological and reporting quality were then assessed and compared between the registered (or with a protocol) and the matched DRMAs.

Eligibility criteria

We included dose-response meta-analysis (DRMA) of binary outcomes, without limitation on the design of original studies that included in a DRMA. A dose-response meta-analysis was defined as a form of meta-analysis that combines dose-response relationship between an independent variable (e.g. sleep duration) and an outcome variable (e.g. all-cause mortality) from similar studies [16,17,18,19,20]. This requires a within study dose-response relationship so that the traditional meta-regression were not covered [21]. To distinguish meta-analysis and pooled analysis, the term “meta-analysis” should contains thorough systematic review components, which has been defined by the Cochrane handbook [1].

We did not include DRMA of continuous outcomes as very few such studies were available. We also excluded the following reports: studies specifically investigating methodology of such analyses; analyses based on individual patient data; and unpublished reports, conference abstracts and other forms of short reports (e.g. brief reports, letters).

Literature search

Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), and Wiley online Library were searched from 1st-Jan-2011 to 31st-Dec-2015 without any language limitation (conducted in 31st-Dec-2015). An updated search was conducted in 1st-Aug-2017. We restricted such time period because very few DRMAs published before 2011. Studies were not included if it was published ahead of print. The search strategy was presented in appendix file (Additional file 1: Appendix 1). The process of literature search was conducted by one experienced author (X.C).

Study selection process

The study selection was conducted by two experienced, methods-trained authors (X.C and L.Y). One author (X.C) is the primary co-developer of the robust error meta-regression (REMR) model for dose-response meta-analysis [18]. The two authors initially screened titles and abstracts to exclude reports that explicitly failed to meet eligibility criteria. Then, they read the full texts to check against the eligibility criteria independently. Afterwards, they independently collected information from each eligible study, and assessed methodological and reporting quality of included DRMAs. For each of the step, the authors carefully cross-checked the collected data. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Definition of scientific quality

The scientific quality of a systematic review or meta-analysis generally contains two components, which were the methodological quality and the reporting quality [10, 22]. The former one refers to the internal validity that reflects the design and conduct of a systematic review or meta-analysis, while the later reflects the reporting.

Data collection and quality assessment

We collected the following background information from each eligible DRMA: name of first author, departments of authors, region of first author, author numbers, year of publication, research topics, journal name, and funding information. We determined that a DRMA registered or with a protocol, if they provided a registration ID, an attachment protocol, or a web linkage of the protocol, which has been described in PRISMA checklist [10]. If a DRMA was registered at PROSPOERO and clinicatrials.gov, we treated it as PROSPERO which is specific for registration of systematic reviews. Those DRMAs claiming registered or developed a protocol, while failed to provide any details and cannot be obtained by our further attempt (searching the supplementary file and the websites of the institution of the first and corresponding author), were not treated as such.

Following a common approach [22,23,24], we used the AMSTAR 1.0 checklist (Assess Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews, AMSTAR) to assess the methodological quality and the PRISMA checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, PRISMA) to assess the reporting quality of included DRMAs [10, 25, 26]. We used AMSTAR 1.0 because version 2.0 was yet to be released in that period. For AMSTAR, we made slight modifications by disaggregating four items. For example, we changed the item “was there duplicate study selection and data extraction?” into two questions: was there duplicate study selection? and was there duplicate data extraction?. We removed the item “was an a priori design provided?”, because this item specifically addresses the issue about our exposure of interest. These modifications resulted in 14 items (Additional file 1: Appendix 2).

For PRISMA, we also made slight modifications by removing the item “protocol and registration” as this item is our exposure of interest. As a result, the modified PRISMA checklist contained 26 items (Additional file 1: Appendix 2).

Matching between registered and control groups

Given the significantly imbalanced distribution in the geographic region and year of publication between DRMAs with protocol registration or development versus those not, we used propensity score matching method, with nearest neighbor approach, in a 1:2 ratio of the two types of DRMAs [27]. We divided geographic region as Asian and Non-Asian (European, America, and Australia) for the matching since previous literatures demonstrated that meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials by author from Asian tends to poorly conducted [4, 28]. We used 1:2 ratio due to the consideration of both the available sample size and the optimal matching (i.e. a 1:1 ratio may result in low power and a 1:3 ratio or more may lead to over-matching). The details of the matching process can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix 3.

Statistical analysis

We assigned one point to each of the items if the DRMA met the requirement or zero if not (we treated “unclear” as not), both for the AMSTAR and PRISMA checklists [21]. Thus the total scores were 14 and 26 points, respectively. The compliance rate of each of the item was used to show the extent of those DRMAs met methodological and reporting checklists.

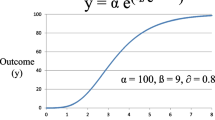

In order to examine if the DRMAs with protocol registration or development would perform better on methodological and reporting quality than those not, we first compared the mean quality scores for AMSTAR and PRISMA between the registered and control group. We used t test for the comparison if the scores were normally distributed. Otherwise, we transformed the scores by the method of ladder of powers [29], which would suggest a best approach to data transformation. The test for normality (Skewness-Kurtosis test) suggested that the AMSTAR total score was normally distributed (P = 0.37), but not the total score for PRISMA (P < 0.01). We subsequently used the cubic transformation for PRISMA total (normality test P = 0.32). The compliance rate of each item was compared by t test and measured with rate difference (RD).

Multivariable regression analysis was used to see if protocol registration or development was associated with better methodological and reporting quality after adjusting any imbalanced basic characteristics. Considering the potential influence of journals, a robust variance by treating each journal as a cluster, was added to address clustering (on the quality) of papers published in the same journal. All the analyses were conducted using R 3.4.2 and Stata 14.0 software with p < 0.05 as statistical significant.

Results

The search initially identified 7061 records. After exclusion of duplicate reports and screening of abstracts, 1306 were potentially eligible. Reading full texts against the eligibility criteria finally identified 529 eligible DRMAs (Fig. 1). Of these 529 DRMAs, 45 (8.51%) registered or developed a protocol. The proportion of protocol registration or development were 17.14, 18.18, 7.14, 5.13, 3.33, 5.88, and 16.67% from 2011 to 2017.

Among the 45 studies, 21 were funded by the World Cancer Research Fund UK with study protocols reported at the official website (https://www.wcrf-uk.org/), 19 were registered at the PROSPERO database (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), 3 provided a supplemented protocol, one on website (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/scientific-advisory-committee-on-nutrition), and one was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). When categorized by country, 26 were from UK, 7 from China, 3 from South Korea, 2 from Canada, 2 from Finland, 2 from Germany, 2 from Sweden, and 1 from the US. By propensity score matching, we included 90 DRMAs for comparison (Additional file 1: Appendix 4).

Table 1 presented the basic characteristics of the two groups. The number of authors and proportion of using reporting checklists in the group of DRMAs with protocol registration and development were significant higher than the matched control group. Other basic variables were balanced for the two groups.

Methodological quality between registered and matched group

Figure 2 outlined the methodological status of the two groups. In the group of DRMAs with protocol registration or development, the median score of AMSTAR was 9 (first to third quartile: 8, 11), and in the group of matched controls the median score was 9 (first to third quartile: 7, 10). The mean score of DRMAs with protocol registration or development [9.47; Standard deviation (SD): 0.29)] was higher (P < 0.01) than the matched group (8.58, SD, 0.20).

For each methodological item, a higher rate of DRMAs with protocol registration or development used duplicate data extraction (RD = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.04, 0.30; P = 0.01), documented the search strategy (RD = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.50; P < 0.01), listed the studies of excluded (RD = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.38; P = 0.02), and assessed the publication bias (RD = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.18; P < 0.01) than the matched control group (Table 2).

Simultaneously, a higher rate of DRMAs with protocol registration or development used the status of publication as an inclusion criterion (RD = 0.10, 95% CI: -0.07, 0.27; P = 0.25) and stated the conflicts of interests (RD = 0.07, 95% CI: -0.02, 0.16; P = 0.14) than matched control group, though statistically insignificant. However, for scientific quality assessment (risk of bias), a higher proportion was observed among the DRMAs in control group (RD = − 0.07, 95% CI: -0.25, 0.11; P = 0.46). There were no obvious rate differences for other items (Table 2).

Reporting quality between registered and matched control group

Figure 3 outlined the reporting status of the two groups. In the group of DRMAs with protocol registration or development, the median score of PRISMA was 22 (first to third quartile: 22, 23), and in the group of matched controls the median score was 22 (first to third quartile: 21, 24). The mean cubic transformed score on group of DRMAs with protocol registration or development (12,967.13, SD: 2480.492) was (P < 0.01) higher than the matched control group (10,848.88, SD: 3224.55).

For each reporting item, we found a higher rate of DRMAs with protocol registration or development presented full electronic search strategy for at least one database (RD = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.29, 0.60; P < 0.01), described methods for publication bias (RD = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.14; P = 0.02), presented the risk of bias across studies (i.e. publication bias, RD = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.18; P < 0.01), discussed limitations at study and outcome level (RD = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.17; P = 0.03), provided a general interpretation of the results (RD = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.08, 0.33; P < 0.01), and described sources of funding and other support (RD = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.28; P < 0.01) than the matched controls (Table 2).

Other items with higher compliance rate among DRMAs with protocol registration or development were: state the process of selecting studies (RD = 0.10, 95% CI: -0.06, 0.26; P = 0.23), describe method of data extraction (RD = 0.10, 95% CI: -0.03, 0.23; P = 0.12), and state the principal summary measures (RD = 0.07, 95% CI: -0.02, 0.16; P = 0.14). No obvious rate difference was observed on other items (Table 2).

Multivariable regression analysis

After adjusting the unbalanced covariates and clustering on journal in the multivariable regression model, we found that protocol registration or development in priori was significant associated with better reporting quality (β= 1446.66, P = 0.012) while not associated with methodological quality (β= 0.06, P = 0.88). A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding 3 DRMAs only provided a supplemented protocol (as well as the 6 matched DRMAs), considering that supplemented protocol does not ensure that it was developed a priori. The results did not showed substantial changes [reporting quality (β= 1366.186, P = 0.031); methodological quality (β= − 0.03; P = 0.93)].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research described the proportion of protocol registration (or development) of dose-response meta-analyses (DRMAs) as well as the first research compared the methodological and reporting quality of DRMAs with protocol registration or development to those not. In this study, we found that only 8.51% of the published DRMAs registered or provided a protocol, while these DRMAs have higher compliance rate on some methodological/reporting items and better total reporting quality than those without a protocol.

There were some differences of our results to an earlier research [24]. In the study, the quality of Cochrane systematic reviews (all requires a protocol) and reviews published in paper-based journals were compared [24], and higher methodology rigors (instead of reporting) of Cochrane systematic reviews were observed. A more recent survey suggested that prospective registration may improve the overall methodological quality of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trial [30]. However, in our study, we only observed a significant improvement on total reporting quality while not for methodological quality. This is likely due to the different types of meta-analysis we aimed at.

Based on our results, for DRMAs failed to provide a protocol, the under complied methodological items were: few of them employed duplicate data extraction, documented the search strategy, documented the scientific quality, and listed the studies of excluded. While the under complied reporting items were: few of them presented full electronic search strategy, stated the process of for selecting studies, described methods for assessing risk of bias within each study, and presented the data on risk of bias of within each study. For both groups, the scientific quality of included studies were seldom documented, this subsequently result in the failing of applying the scientific quality to formulate conclusions.

The AMSTAR and PRISMA checklists were widely used to assess methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [30, 31]. The AMSTAR was first released in 2007 that was of two years earlier than the PRISMA checklist (released in 2009) [10, 26]. In our research, the PRISMA checklist was generally better complied than the AMSTAR (See Figs. 2 and 3). This may partly due to the promotion of academic journals, as a large number of journals require the submissions should in accordance with the PRISMA checklist. The phenomenon however may reflect a serious issue — the lack of focus on methodology of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Our findings suggested that even for DRMAs with a protocol, many of the methodological items were poorly conducted. It is expected more attention should be paid to the methodology of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the future.

The findings of current research have verified the importance of protocol development or registration of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Protocol may benefits healthcare decision in two aspects. First, evidence is the key body for evidence based practice, and a prior registration of systematic reviews and meta-analyses benefits the evidence production that further help to better healthcare decision. In addition, a prior registration may make sense to improve the efficiency of decision making given the potential role on reducing overlapped evidence production.

There were some strengthens of current research that help to enhance the credibility of our results. We adopted a comprehensive and up-to-date search, where we almost included all potential published DRMAs during the past 7 years. We employed the 1:2 matching by propensity score method and multiple regression to control the potential confounders on our results. We blinded the process of quality assessment to avoid objective bias. However, several limitations should not be ignored. In this article, we did not take account for the correlation between AMSTAR and PRISMA. Actually, these two checklists are highly correlated since some items of them were overlapped or even the same. We did not mix them together because we believe that comparing methodological quality and reporting quality separately is of more practical significance. In addition, AMSTAR and PRISMA are currently the optimal tools to reflect the quality of systematic reviews, yet it is impossible for them to cover all of the domains. Our results highly rely on the validity and reliability of the two checklists. Third, we failed to distinguish the potential heterogeneity among different registration methods (e.g. PROSPERO, documented protocol) due to the limited numbers of DRMAs with protocol. Fourth, the information of protocol registration or development was collected based on the reporting of these published DRMAs, it is possible that a small amount of DRMAs may publish a protocol in advance but not mentioned in the final context, which would lead to selective bias for our results. Fifth, for DRMAs with protocol registration or development, many of which shared the same first author that may influence the representativeness.

Conclusions

Based on the current survey, only a small proportion of published DRMAs completed protocol registration or development and the methodological quality of these DRMAs is suboptimal. DRMAs with a protocol had better reporting quality and higher compliance rate of several methodological quality related items than those not. Therefore, protocol registration or development may benefit for evidence based practice that is highly desirable for all DRMAs.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

Assess Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

- DRMA:

-

Dose-response meta-analysis

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PRISMA-P:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

- RD:

-

Rate difference

- REMR:

-

Robust error meta-regression

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Chandler J, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Davenport C, Clarke MJ. Chapter 1: Introduction. In: Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston MS (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017), Cochrane, 2017. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/pdf-versions. Accessed in 7th Oct 2018.

Furuya-Kanamori L, Bell KJ, Clark J, Glasziou P, Doi SA. Prevalence of differentiated thyroid Cancer in autopsy studies over six decades: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(30):3672–9.

Liu TZ, Xu C, Rota M, Cai H, Zhang C, Shi MJ, et al. Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality: a flexible, non-linear, meta-regression of 40 prospective cohort studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;32:28–36.

Ioannidis JP. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 2016;94:485–514.

Ebrahim S, Bance S, Athale A, Malachowski C, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analyses with industry involvement are massively published and report no caveats for antidepressants. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:155–63.

Siontis KC, Hernandez-Boussard T, Ioannidis JP. Overlapping meta-analyses on the same topic: survey of published studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f4501.

Poolman RW, Abouali JA, Conter HJ, Bhandari M. Overlapping systematic reviews of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction comparing hamstring autograft with bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft: why are they different? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1542–52.

Page MJ, Altman DG, McKenzie JE, Shamseer L, Ahmadzai N, Wolfe D, et al. Flaws in the application and interpretation of statistical analyses in systematic reviews of therapeutic interventions were common: a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;95:7–18.

Weir A, Rabia S, Ardern C. Trusting systematic reviews and meta-analyses: all that glitters is not gold! Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1100–1.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34.

PROSPERO. International prospective register of systematic reviews. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage. In: . Accessed in 7th Dec. 2017.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1).

Andrade R, Pereira R, Weir A, Ardern CL, Espregueira-Mendes J. Zombie reviews taking over the PROSPERO systematic review registry. It's time to fight back! Br J Sports Med. 2017:bjsports-2017-098252.

Davies S. The importance of PROSPERO to the National Institute for Health Research. Syst Rev. 2012;1:5.

Berlin JA, Longnecker MP, Greenland S. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic dose-response data. Epidemiology. 1993;4:218–28.

Orsini N, Li R, Wolk A, Khudyakov P, Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:66–73.

Xu C, Doi SA. The robust-error meta-regression method for dose-response meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018;16(3):138–44.

Liu Q, Cook NR, Bergström A, et al. A two-stage hierarchical regression model for meta-analysis of epidemiologic nonlinear dose–response data. Comput Stat Data An. 2009;53:4157–67.

Xu C, Thabane L, Liu TZ, et al. Flexible piecewise linear model for investigating dose-response relationship in meta-analysis: methodology, examples, and comparison. J Evid-Based Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12339.

Xu C, Liu Y, Jia PL, et al. The methodological quality of dose-response meta-analyses needed substantial improvement: a cross-sectional survey and proposed recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;107:1–11.

Shea B, Moher D, Graham I, Pham B, Tugwell P. A comparison of the quality of Cochrane reviews and systematic reviews published in paper-based journals. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25:116–29.

Gómez-García F, Ruano J, Gay-Mimbrera J, Aguilar-Luque M, Sanz-Cabanillas JL, Alcalde-Mellado P, et al. Most systematic reviews of high methodological quality on psoriasis interventions are classified as high risk of bias using ROBIS tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;92:79–88.

Jadad AR, Cook DJ, Jones A, Klassen TP, Tugwell P, Moher M, et al. Methodology and reports of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a comparison of Cochrane reviews with articles published in paper-based journals. JAMA. 1998;280:278–80.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.

Guertin JR, Rahme E, Dormuth CR, LeLorier J. Head to head comparison of the propensity score and the high-dimensional propensity score matching methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:22.

Qin Y, Yao L, Shao F, Yang K, Tian L. Methodological quality assessment of meta-analyses of hyperthyroidism treatment. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50(1):8–16.

Tukey JW. Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley; 1977.

Ge L, Tian JH, Li YN, Pan JX, Li G, Wei D, et al. Association between prospective registration and overall reporting and methodological quality of systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;93:45–55.

Ruano J, Aguilar-Luque M, Isla-Tejera B, Alcalde-Mellado P, Gay-Mimbrera J, Hernández-Romero JL, et al. Relationships between abstract features and methodological quality explained variations of social media activity derived from systematic reviews about psoriasis interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;101:35–43.

Acknowledgments

I (X.C) would like to express my deep appreciation for Prof. Suhail A.R Doi (Qatar University) for his guidance on me of synthesis methods for dose-response data.

Funding

This study was supported by the project of Taihe Hospital (No. 2016JJXM070). X.C was supported by Master Scholarship of Wuhan University (2015–2016) and Doctoral Scholarship of Sichuan University (2017–2020). There is no role for the funding in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and writing.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its additional file.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XC, ZC and CL-L conceived and designed the study; LY, JP-L and XC contributed to the data acquisition; XC, CL-L and ZC analyzed the data; XC, ZC, and JP-L and drafted the manuscript; XC, ZC, CL-L, and G.MY interpreted the results; All authors provided substantial revision for the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published, agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategy, modified checklist for quality assessment, R code and hist plots of propensity score matching, and list of included DRMAs. (DOCX 122 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, C., Cheng, LL., Liu, Y. et al. Protocol registration or development may benefit the design, conduct and reporting of dose-response meta-analysis: empirical evidence from a literature survey. BMC Med Res Methodol 19, 78 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0715-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0715-y