Abstract

Background

Up to a fourth of patients at emergency department (ED) presentation suffer from acute deterioration of renal function, which is an important risk factor for bleeding events in patients on oral anticoagulation therapy. We hypothesized that outcomes of patients, bleeding characteristics, therapy, and outcome differ between direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and vitamin-K antagonists (VKAs).

Methods

All anticoagulated patients older than 17 years with an impaired kidney function treated for an acute haemorrhage in a large Swiss university ED from 01.06.2012 to 01.07.2017 were included in this retrospective cohort study. Patient, treatment, and bleeding characteristics as well as outcomes (length of stay ED, intensive care unit and in-hospital admission, ED resource consumption, in-hospital mortality) were compared between patients on DOAC or VKA anticoagulant.

Results

In total, 158 patients on DOAC and 419 patients on VKA with acute bleeding and impaired renal function were included. The renal function in patients on VKA was significantly worse compared to patients on DOAC (VKA: median 141 μmol/L vs. DOAC 132 μmol/L, p = 0.002). Patients on DOAC presented with a smaller number of intracranial bleeding compared to VKA (14.6% DOAC vs. 22.4% VKA, p = 0.036). DOAC patients needed more emergency endoscopies (15.8% DOAC vs, 9.1% VKA, p = 0.020) but less interventional emergency therapies to stop the bleeding (13.9% DOAC vs. 22.2% VKA, p = 0.027). Investigated outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Conclusions

DOAC patients were found to have a smaller proportional incidence of intracranial bleedings, needed more emergency endoscopies but less often interventional therapy compared to patients on VKA. Adapted treatment algorithms are a potential target to improve care in patients with DOAC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Any type of anticoagulation is associated with the risk of bleeding complications [1]. Frequency of bleeding and bleeding locations, however, may differ among different classes of anticoagulants. Intracranial haemorrhage and gastrointestinal bleedings (GIB) are the most common bleeding complications leading to major haemorrhage in patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) therapy [2]. Compared to classic vitamin K antagonist therapy (VKA), DOAC were found to be associated with a 50% reduction of intracranial haemorrhage [3, 4]. In contrast to intracranial haemorrhage, the incidence of GIB in DOAC patients is at least comparable to VKA or may be even higher for dabigatran and rivaroxaban [5].

Treatment of special patient groups with the need of anticoagulation e.g. patients with chronic kidney diseases (CKD) or at risk for CKD [2, 6] may be more demanding. Patients with atrial fibrillation and CKD are a special treatment challenge, because they combine an increasing risk of both, bleeding in general and thrombotic complications [7, 8]. A previous study found major bleeding events in elderly patients on DOAC therapy to be associated with a decline of renal function [9]. All registered DOAC are eliminated to a certain extent through the kidneys and thus all have limitations in patients with CKD [7]. However, recent clinical trials suggest that DOAC may be also beneficial in comparison to VKA in CKD patients [4, 10].

Current clinical guidelines recommend careful considerations about the risk and benefit in patients with impaired kidney function and need for anticoagulation [11] and specifically emphasis on the need of a stable situation to assess the kidney function and warn not to confuse acute renal impairment with CKD [7]. In contrast to this premise of a “stable situation”, up to a fourth of patients with whom an emergency physician is confronted at emergency department (ED) admission with an acute medical problem suffer from acute deterioration of renal function with unclear dimensions and dynamics [12]. This acute influence of situational environmental factors is difficult to represent in classical RCTs, which is why real-world data is needed for this purpose [13, 14].

Therefore, our primary study aim is to analyse bleeding and patient characteristics in patients with impaired kidney function at ED admission due to acute haemorrhage on DOAC therapy and compare them to patients on VKA. Furthermore, we investigate clinical outcomes (in-hospital mortality) and procedural outcomes, i.e. length of stay in the ED and in hospital, intensive care unit (ICU) transmission and hospitalisation rate as well as ED resource consumption, all compared to patients on VKA.

Methods

Study design & setting

This is a retrospective cohort study of the adult ED of the Bern University Hospital, Inselspital, Switzerland. Our ED is responsible for the emergency treatment of about 50,000 patients per year from a catchment area of 2 million people.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

This study included all patients treated for acute haemorrhage at our ED from 1st of June, 2012 to 30th of June, 2017 with i) VKA or DOAC therapy for full anticoagulation and ii) an impaired kidney function at admission defined as an glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ≤60 mL/min [15].

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were i) no creatinine testing performed at ED admission, ii) GFR > 60 mL/min at admission, iii) no oral anticoagulation medication documented in the medical report, and iv) no acute bleeding complication at ED admission.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary study outcomes were bleeding and patient characteristics on DOAC therapy compared to VKA.

Secondary outcomes were procedural outcomes (length of stay in the ED and in hospital, ICU transmission and hospitalisation rate as well as ED resource consumption) and clinical outcomes, i.e. in-hospital mortality.

Definitions

The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) classification was used for classification of kidney impairment [15], with the severity grades according to the GFR of 45–60 mL/min, 30-44 mL/min, 15-29 mL/min, and < 15 mL/min. The GFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation as it was recommended by the National Kidney Foundation because of the reliability across all CKD stages [16]. Although the Cockroft-Gault equation for GFR estimation was applied in the landmark clinical trials of DOAC in atrial fibrillation, it has several limitation in its application particularly in patients that are overweight and older [7].. Since the implementation of the Cockroft-Gault equation was not feasible in our retrospective ED study as patient weight is not documented for all ED patients we performed the analysis using the CKD-EPI equation which is calculated automated in all patients. Polypharmacy was defined as the use of five or more drugs [17].

To describe comorbidities of a patient, the Charlson comorbidity index was used including parameter such as liver disease, CKD, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and congestive heart failure [18].

Major bleeding were defined for our study according to the international society of thrombosis and haemostasis (ISTH) definition as fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in critical organ or transfusion of at least two erythrocytes concentrates [19]. As a documented haemoglobin drop of at least 20 g/L was not feasible to determine reliable in the ED setting, the criterion was not used.

In Switzerland, the costs incurred in an ED for each ambulatory procedure or physician/nurse work are settled in “tarmed: tarif médical” points which, is a system of procedure codes. This point system used in Switzerland corresponds to 1 Swiss franc per 1 point billed. We indicate the total ED resource consumption during treatment in “tax points” as the sum of all procedures.

Data handling

A keyword search was performed through all medical reports between 01.06.2012 to 01.07.2017 containing all the substance classes and brand names of oral anticoagulants approved in Switzerland (substance classes: rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, and edoxaban, phenprocoumon, warfarin, and acenocoumarol), combined with the logic operator “OR”. Medical ED reports in our department including patient history, diagnosis, clinical findings, and medication administered are stored electronically in an ED patient database (E-Care, ED 2.1.3.0, Turnhout, Belgium). We excluded all search results of cases without creatinine testing at ED admission. Finally, the eligibly criteria were evaluated by manual full text analysis of each found medical ED report.

The following parameter were extracted directly from the database: age, sex, triage level (which is routinely determined by special trained nurses using the Swiss triage scale [20]), type of referral, all procedural outcomes, in-hospital mortality, as well as creatinine and INR values on admission. Using full-text analysis of the medical report, the following parameter were manually extracted: trauma, information on anticoagulation (indication for therapy, type of medication, additional antiplatelet therapy), comorbidities to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index, arterial hypertension and polypharmacy, bleeding characteristics i.e. location and extent of bleeding (major bleeding and the discharge diagnosis of a haemorrhage shock) as well as information on the therapy of the bleeding. Interventional therapies included surgery, coiling, clipping, embolization, angiography, drainage, and variceal ligation. A diagnostic endoscopy was not considered an interventional therapy.

Group description and data analysis

The DOAC group used for analysis combined all patients on any DOAC approved in Switzerland (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban and rivaroxaban) on ED admission. For group comparison we formed a VKA group, including all patients under phenprocoumon and acenocumarol at ED admission. All statistical analysis for this work was performed with Stata® 13.1 (StataCorp, The College Station, Texas, USA).

For descriptive analysis the distribution of categorical variables was presented as the absolute accompanied by the relative number in each category [n (%)] and of continuous outcomes with the median accompanied by the interquartile range (IQR) as normal distribution of continuous outcomes could not be ensured.

To compare the study groups (DOAC vs. VKA) Chi square and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used, as appropriate. The significance level was set to p < 0.05. As this is an exploratory data analysis, there was no adjustment for multiple testing.

Ethical considerations

The present study is registered with the competent ethics committee of Canton Bern, Switzerland under the number 073/2015 and according to Swiss law, the need to obtain informed consent for the study was waived.

Results

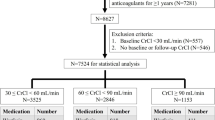

Anticoagulation key-word search between 01.06.2012 to 31.06.2017 resulted in 14,684 patients out of 199,982 consultations (Fig. 1).

In 2391 patients, no creatinine measurements were performed during ED workup and 8435 patients had a renal function above the cut-off value (GFR > 60 ml/min) and were therefore excluded.

By manual screening and exclusion of 3281 patients without an acute diagnosis of bleeding (n = 3196), unclear or no-anticoagulation status at ED admission (n = 80), and five patients with irregular consultation documentation (e.g. duplicates), we finally included 158 ED consultations on DOAC and 419 consultations on VKA. The ratio between VKA and DOAC patients decreased over the study years. While in the first year of the study (2012/2013) 91.0% of the patients were on VKA, in the last year of the study 58.2% (2016/2017) were on VKA therapy (p < 0.001).

Patient characteristics

An overview of all patient characteristics is presented in Table 1.

There were no significant differences regarding gender and age (p = 0.771 and p = 0.774) between both anticoagulation groups (see Table 1). The renal function in patients on VKA was significantly (p = 0.002) worse compared to patients on DOAC. Especially in the GFR < 15 mL/min group 7.4% patients were on VKA vs. 0.6% on DOAC. Significant more patients (p = 0.029) on DOAC (5.7%) had a documented liver insufficiency compared to VKA (2.1%). The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) had a median of 5 (IQR 4–7) points in both groups (p = 0.143). There was no significant group difference regarding polypharmacy (p = 0.352).

Consultation and anticoagulation characteristics

The type of referral or triage category was similar in both two study groups (Table 2). Trauma was found more often in VKA patients (32.9%, n = 138) compared to DOAC patients (24.1%, n = 38, p = 0.039). In the DOAC group, the majority of DOAC patients were on rivaroxaban (n = 141, 89.2%). Nine patients were on apixaban (5.7%), six on dabigatran (3.8%), and two (1.3%) on edoxaban. In the VKA group, the majority of 415 patients were on phenprocoumon (99.0%); 4 patients were on acenocumarol (1.0%). Regarding indication for anticoagulation, the most common indication for anticoagulation in all patients was atrial fibrillation (49.7%). Significant group differences were found regarding “mechanical heart valve” and “venous embolism” as indications for anticoagulation (p = 0.009). Additional antiplatelet therapy did not differ significantly between the two study groups (p = 0.346).

The median INR in patients with VKA was 2.4 (IQR: 1.7–3.3), and in patients with DOAC 1.3 (IQR 1.1.-1.5). Using the INR range 2.0–3.0 to the definition of therapeutic range, 31.3% of the VKA patients were over and 34.4% were under the therapeutic range.

Bleeding characteristics

Apart from a higher number of intracranial bleedings including intracerebral bleedings in the VKA group (22.4% vs. 14.6% in DOAC patients, p = 0.036), no significant differences in the distribution of bleeding locations were found, see Table 3. The most common location was GIB in both anticoagulation groups (DOAC 34.8% vs. VKA 28.6%, p = 0.135). The incidence of major bleeding events did not differ significantly between the study groups (p = 0.784). Major bleeding was not significantly associated with the GFR in the DOAC (p = 0.723) respectively VKA group (p = 0.795).

VKA patients needed a higher number of interventions to stop the bleeding compared to DOAC (22.2% vs. 13.9%, p = 0.027) and a smaller number needed gastroduodenoscopies (VKA 9.1% vs. DOAC 15.8%, p = 0.020), see Table 4.

Clinical outcomes

Most patients were treated in hospital (DOAC 92.4% vs. VKA 90.2%, p = 0.431) and 42.0% were admitted to ICU (DOAC 38.2% vs. VKA 43.4%, p = 0.264) without group difference for both outcomes, see Table 5. No differences were observed regarding ED resource consumption, LOS in hospital or the ED as well as in-hospital mortality.

Discussion

In this study patients with impaired kidney function and bleeding complications at ED admission, DOAC patients were found to have a lower proportional incidence of intracranial haemorrhage, needed more emergency endoscopies, but less interventional therapies to stop the bleeding compared to patients on VKA therapy.

In our study, the group of patients with VKA therapy in general had a worse renal function compared to DOAC mostly due to patients with impaired kidney function with GFR < 15 ml/min, a range with very limited experience with DOAC and contraindications for most DOAC. A relevant number of patients on DOAC therapy were found to have a renal function < 30 ml/min at admission that might potentially lead to accumulation of anticoagulant medications [21]. This finding underlines the fact that all of the DOAC have dosing regimens that need close monitoring of the renal function which have be taken into account for selection of the correct dosage.

In such patients current prescribing patterns may lead to increased thrombo-embolic risk and increased bleeding complications thus measurement of serum DOAC levels might be useful to guide acute treatment as well as further dose adjustments.

Additional platelet aggregation inhibitor therapy that could further increase the risk of bleeding and is associated with a higher and more severe bleeding risk [22, 23] was similarly distributed between the study groups.

Bleeding location and therapy

Most of the bleeding locations occurred in a comparable frequency in both, DOAC and VKA patients with impaired renal function. GIB are a typical bleeding location for DOAC especially on rivaroxaban therapy [24]. For both anticoagulant groups, GIB were the most common bleeding leading to ED admission in our study. Intracranial bleedings were more prevalent in the VKA group. As the study population consisted of patients admitted for major hemorrhage, less frequent occurrence of one bleeding location might be caused by a higher frequency of another bleeding location and vice versa. Thus, only proportional incidences could be determined in this study.

Patients with GIB under DOAC therapy received more endoscopies overall and especially more gastroscopies compared to VKA, although VKA patients received more interventional therapies. Several reasons might explain these findings. First, physicians’ management of DOAC-associated bleedings might differ as the specific reversal agents of DOACs are expensive and may not be available in some ED. Therefore, treating physicians are more cautious as a multi-nominal survey about bleeding management demonstrated [25]. This fact is reflected by another study of our group that found an increased application of prothrombin complex concentrates for reversal of DOAC compared to VKA bleedings in clinical practice [26]. A recent meta-analysis of PCC and andexanet alfa for management of factor Xa inhibitor related bleeding, found similar rates of good hemostasis for both medications but a tendency to higher complication rates on andexanet alfa [27]. Second, several studies suggested a higher rate of GIB in DOAC patients [5, 28], thus, a wait-and-see approach might seem an inappropriate choice for the attending physician in DOAC patients with suspected GIB as the extend of the bleeding in often unclear. Third, VKA reversal is straightforward und routinely measurable compared to DOAC, thus, some interventional procedures might have been performed in VKA patients, while DOAC interventions were postponed.

Outcomes

No significant differences were found in the investigated outcomes between the DOAC and VKA group. The hospitalisation and ICU transmission rates were high, a finding that is explained by the high number of GIB and intracranial bleedings in both groups needing close clinical monitoring or further invasive therapies.

Limitations

Due to the limitations imposed by the size of the study and the retrospective design, there are potential confounders that were not considered in our study. Furthermore, despite the adequate documentation of complications in a tertiary hospital setting and high number of patients on both anticoagulant group, it is possible that the group sizes were still not sufficient in order to find differences in infrequent outcomes such as in-hospital mortality. Because of the monocentric design transferability to other settings is only possible to a limited extent and should be performed carefully. These limitations are not unique to our study, but rather apply to most observational pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Investigation of real-word data can be an important complement to randomized-controlled-trails, however, conclusions must be drawn with great caution due to the uncontrolled confounding factors [13, 14]. Also, we had no information on the chronicity of CKD or on the duration of the anticoagulation therapy. A single creatinine obtained during emergency admission can only provide a snapshot of the patient’s renal function. The same applies for the INR values, e.g. after reversal of VKA with PCC. Furthermore, levels of DOAC or aPTT were not measured routinely over the study period, thus the decision how to treat a patient on DOAC was often based on anamnestic data of DOAC intake. There is growing evidence, that NOAC level measurements should be standard practice, especially in at-risk populations such as patients with renal insufficiency [29].

It is well known that decisions in emergency patients have to be based on often incomplete findings and have to be made under time pressure, which does not allow the detailed collection of follow-up parameters [30,31,32]. In line with the local prevalence of anticoagulant medications most investigated patients were admitted on rivaroxaban [2]. Thus, separate analysis or comparison of different DOAC or stratified presentations of the outcome by GFR group was not possible due to small numbers of patients in those subgroups. With the fast adoption of DOAC including elderly patients over the study years, more DOACs were subscribed to patients with pre-existing conditions and therefore at risk for an impaired kidney function and bleedings. With our data, the exact impact on the results cannot be stated. However, in our opinion, the main findings of a lower proportional incidence of intracranial haemorrhage, more emergency endoscopies and less interventional therapies in DOAC patients remain untouched by this finding.

Conclusion

Compared to VKA, emergency admissions due to acute haemorrhage on anticoagulation therapy with impaired renal function on presentation on DOAC therapy had a lower incidence of intracranial haemorrhage. GIB in DOAC patients needed a higher number of gastroduodenoscopies but less interventional therapies to stop the bleeding compared to VKA therapy.

Further prospective multi-centre research in the special patient population of patient with impaired renal function including DOAC level measurements is necessary. Recent developments with specific antidotes and rapidly and readily available level measurements may optimize future therapy in this special patient population.

Availability of data and materials

For interested researchers the analysed dataset is available from the corresponding author according to Swiss law.

Abbreviations

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- DOAC:

-

direct oral anticoagulant

- ED:

-

emergency department

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- VKA:

-

vitamin K antagonists

References

Landefeld CS, Beyth RJ. Anticoagulant-related bleeding: clinical epidemiology, prediction, and prevention. Am J Med. 1993;95(3):315–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(93)90285-W.

Sauter TC, Amylidi A-L, Ricklin ME, Lehmann B, Exadaktylos AK. Direct new oral anticoagulants in the emergency department: experience in everyday clinical practice at a Swiss university hospital. Eur J Intern Med. April 2016;29:e13–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.12.009.

Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD. u. a. comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. März 2014;383(9921):955–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0.

Raccah BH, Perlman A, Danenberg HD, Pollak A, Muszkat M, Matok I. Major bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke with direct Oral anticoagulants in patients with renal failure. Chest. Juni 2016;149(6):1516–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.029.

Cheung K-S, Leung WK. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants: risk, prevention and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(11):1954–63. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i11.1954.

Di Lullo L, Ronco C, Cozzolino M, Russo D, Russo L, Di Iorio B, u. a. Nonvitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in chronic kidney disease patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res. Juli 2017;155:38–47.

Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L. u. a. the 2018 European heart rhythm association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur heart J. 21. April. 2018;39(16):1330–93.

Reinecke H, Brand E, Mesters R, Schäbitz W-R, Fisher M, Pavenstädt H. u. a. dilemmas in the Management of Atrial Fibrillation in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. April 2009;20(4):705–11. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007111207.

Khan F, Huang H, Datta YH. Direct oral anticoagulant use and the incidence of bleeding in the very elderly with atrial fibrillation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. November 2016;42(4):573–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-016-1410-z.

Shin J-I, Secora A, Alexander GC, Inker LA, Coresh J, Chang AR. u. a. risks and benefits of direct Oral anticoagulants across the Spectrum of GFR among incident and prevalent patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin J am Soc Nephrol. 7. August. 2018;13(8):1144–52.

Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, Antz M, Diener H-C, Hacke W, u. a. Updated European Heart Rhythm Association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin-K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: Executive summary. Eur Heart J. 9. Juni 2016;ehw058.

Challiner R, Ritchie JP, Fullwood C, Loughnan P, Hutchison AJ. Incidence and consequence of acute kidney injury in unselected emergency admissions to a large acute UK hospital trust. BMC Nephrol [internet]. Dezember 2014 [zitiert 2. August 2019];15(1). Verfügbar unter. 2014. https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2369-15-84.

Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Pan GJD, Gray GW, Gross T, Hunter NL. u. a. real-world evidence - what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J med. 8. Dezember. 2016;375(23):2293–7.

Corrigan-Curay J, Sacks L, Woodcock J. Real-world evidence and real-world data for evaluating drug safety and effectiveness. JAMA. 4. September. 2018;320(9):867–8.

Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Nahas ME. L., Astor BC, Matsushita K, u. a. the definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: a KDIGO controversies conference report. Kidney Int. Juli 2011;80(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.483.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI. u. a. a new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann intern med. 5. Mai. 2009;150(9):604–12.

Monégat M, Sermet C, Perronnin M, Rococo E. Polypharmacy: definitions, measurement and stakes involved. Rev Lit Meas Tests. 2014.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8.

Schulman S, Kearon C. Subcommittee on control of anticoagulation of the scientific and standardization Committee of the International Society on thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost JTH. April 2005;3(4):692–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x.

Rutschmann OT, Hugli OW, Marti C, Grosgurin O, Geissbuhler A, Kossovsky M, u. a. Reliability of the revised Swiss Emergency Triage Scale: a computer simulation study. Eur J Emerg Med Off J Eur Soc Emerg Med. 14. Februar 2017;

Lutz J, Jurk K, Schinzel H. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with chronic kidney disease: patient selection and special considerations. Int J Nephrol Renov Dis. 12. Juni 2017;10:135–43. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJNRD.S105771.

Mega J, Braunwald E, Mohanavelu S, Burton P, Poulter R, Misselwitz F. u. a. rivaroxaban versus placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet. Juli 2009;374(9683):29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60738-8.

Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, Lawler E, Cook JR. Warfarin plus Aspirin after Myocardial Infarction or the Acute Coronary Syndrome: Meta-Analysis with Estimates of Risk and Benefit. Ann Intern Med. 16. August 2005;143(4):241.

Abraham NS, Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Sangaralingham LR, Shah ND. Gastrointestinal Safety of Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Large Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology. 1. April 2017;152(5):1014–1022.e1.

Shaw JR, Castellucci L, Siegal D, Stiell I, Syed S, Lampron J, u. a. Management of direct oral anticoagulant associated bleeding: Results of a multinational survey. Thromb Res. März 2018;163:19–21.

Müller M, Eastline J, Nagler M, Exadaktylos AK, Sauter TC. Application of prothrombin complex concentrate for reversal of direct oral anticoagulants in clinical practice: indications, patient characteristics and clinical outcomes compared to reversal of vitamin K antagonists. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-019-0625-3.

Luo C, Chen F, Chen Y-H, Zhao C-F, Feng C-Z, Liu H-X. u. a. prothrombin complex concentrates and andexanet for management of direct factor Xa inhibitor related bleeding: a meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. März 2021;25(6):2637–53. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202103_25428.

Desai J, Kolb J, Weitz J, Aisenberg J. Gastrointestinal bleeding with the new oral anticoagulants – defining the issues and the management strategies. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(08):205–12. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH13-02-0150.

Moner-Banet T, Alberio L, Bart P-A. Does one dose really fit all? On the monitoring of direct Oral anticoagulants: a review of the literature. Hamostaseologie. Juni 2020;40(2):184–200. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1113-0655.

Ilgen JS, Humbert AJ, Kuhn G, Hansen ML, Norman GR, Eva KW. u. a. assessing diagnostic reasoning: a consensus statement summarizing theory, practice, and future needs. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. Dezember 2012;19(12):1454–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12034.

Kämmer JE, Hautz WE, Herzog SM, Kunina-Habenicht O, Kurvers RHJM. The Potential of Collective Intelligence in Emergency Medicine: Pooling Medical Students’ Independent Decisions Improves Diagnostic Performance. Med Decis Making. 29. März 2017;0272989X1769699.

Hautz WE, Kämmer JE, Hautz SC, Sauter TC, Zwaan L, Exadaktylos AK, u. a. Diagnostic error increases mortality and length of hospital stay in patients presenting through the emergency room. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 8. Mai 2019;27(1):54.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter Rhyner Foundation for their funding of DOAC research at the Inselspital, University Hospital Bern as well as the Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, and for the ad personam grant «Young Talents in Clinical Research» for MM.

Statement regarding experiments on humans

For this retrospective cohort study no experiments on humans were performed.

All research methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding

Funding for present work was received from the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter Rhyner Foundation by independent research grants awarded to MM (research about ED resources and TCS for DOAC research). The funding organisation had no role in any aspects of in conducting the research, drafting or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design and drafting of the manuscript was done by MM and TCS. MM performed statistical analyses of data. Data collection and extraction was performed by MT. MT furthermore helped with interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. AKE, SA und MN helped with the study design, helped with the interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and therefore agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study is registered with the competent ethics committee of Canton Bern, Switzerland under the number 073/2015. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the competent ethics committee of Canton Bern.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

TCS has received research grants and lecture fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo as well as the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter Rhyner Foundation. MM has received a research grant from the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter Rhyner Foundation. MN has received research grants or lecture fees from Bayer, CSL Behring, Roche diagnostics, and Instrumentation Laboratory. AKE is member of the advisory boards of all registered DOAC. MT and SA report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, M., Traschitzger, M., Nagler, M. et al. Impaired kidney function at ED admission: a comparison of bleeding complications of patients with different oral anticoagulants. BMC Emerg Med 21, 105 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00497-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00497-1