Abstract

Background

Fracture and dislocation of the shoulder are usually identifiable through the use of plain radiographs in an emergency department. However, other significant soft tissue injuries can be missed at initial presentation. This study used contrast enhanced magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) to determine the pattern of underlying soft tissue injuries in patients with traumatic shoulder injury, loss of active range of motion, and normal plain radiography.

Methods

A prospective, observational cohort study. Twenty-six patients with acute shoulder trauma and no identifiable radiograph abnormality were screened for inclusion. Those unable to actively abduction their affected arm to 90° at initial presentation and at two week’s clinical review were consented for MRA.

Results

Twenty patients (Mean age 44 years, 4 females) proceeded to MRA. One patient had no abnormality, three patients showed minimal pathology. Four patients had an isolated bony/labral injury. Eight patients had injuries isolated to the rotator cuff. Four patients had a combination of bony and rotator cuff injury. Four patients were referred to a specialist shoulder surgeon following MRA and underwent surgery.

Conclusions

Significant soft tissue pathology was common in our cohort of patients with acute shoulder trauma, despite the reassurance of normal plain radiography. These patients were unable to actively abduct to 90° both at initial presentation and at two week’s post injury review. A more aggressive management and diagnostic strategy may identify those in need of early operative intervention and provide robust rehabilitation programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Shoulder pain is a significant cause of morbidity in the general population. It is estimated to be the third most common cause of musculoskeletal consultation in primary care even though only approximately 50% of people with shoulder pain will actually consult their family doctors [1]. The majority of shoulder problems have been allocated into three major categories: namely, arthritis, soft tissue injury and intra-articular injury or instability. It is the latter two categories in particular that present diagnostic problems and challenges in emergency medicine and are the focus of this study. The majority of patients seen in the emergency department (ED) following shoulder trauma are investigated using plain radiographs. In the UK those without evidence of fracture or dislocation are typically given the non-specific diagnosis of a ‘shoulder strain’. The nature of this ‘strain’ is usually ill defined, despite the likelihood that soft tissue injuries such as rotator cuff tears, glenoid labrum tears or subacromial bursitis can lead to significant morbidity and some may warrant early surgical intervention.

Ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are regularly used to detect shoulder soft tissue injury. In terms of deciding the superior diagnostic test for this injury, a Cochrane review concluded that although either imaging technique could be used for full thickness tears, there were too few studies available to state superiority for partial tears [2]. For other injuries such a glenoid labrum tears, an MRI can be enhanced by an intra-articular injection of radio-opaque dye resulting in magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA). The radio-opaque dye acts as contrast material that helps to delineate intra-articular structures and outline abnormalities.

There are no studies on the examination and imaging diagnosis of acute soft tissue shoulder injuries. Systematic reviews [1, 3,4,5,6,7] do not refer to examination in the acute clinical setting and one review excluded all studies which had traumatic origin [1].

We undertook this work as a pilot study in order to ascertain the implications of MRA on acute traumatic shoulder injuries presenting to the ED. The aim was to investigate the impact of MRA on diagnosis and subsequent management and to determine the pattern of underlying soft tissue injuries in patients with traumatic shoulder injury.

Methods

A prospective observational cohort study was conducted in the ED at Manchester Royal Infirmary. This department is a University affiliated teaching hospital and sees an average of 100,000 acute attendances per year. Clinicians assess over 900 shoulder injuries per year, 67% of which are soft issue injuries. This constitutes the fourth most common musculoskeletal injury in our ED.

Subjects

Adult patients were consecutively recruited from November 2010 to March 2011. Therefore this was a snap shot of the patients seen at the ED over a period of time for which funding for the gadolinium enhanced MRI scans was available. Patients presented to the ED with a significant, acute, traumatic injury to the shoulder within the previous 48 h. All underwent physical examination by an ED clinician involved in the project (MJC, JPB, DH, SC,) who requested plain radiographs. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied based on the clinical and radiographic results.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included if there was no evidence of fracture or dislocation on plain radiography and were unable to actively abduct the shoulder beyond 90°. This joint angle was chosen based on the opinion of the study research team as an easy shoulder angle to assess accurately in clinical practice without a goniometer. Patients with these criteria were reviewed two week’s later in the ED. At this review, if patients were symptomatic and still unable to actively abduct their shoulder beyond 90° were invited to participate in the study. Those who could abduct their shoulder beyond 90° after two weeks were discharged to their GP.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had a clear evidence of bone or joint injury on plain radiography or if they were pregnant, in prison custody, had previous ipsilateral shoulder surgery and previous ipsilateral documented shoulder pathology or were unable to provide informed consent. For the MRA, additional exclusions were claustrophobia, cochlear implants, any metal objects in the body including joint prostheses, cardiac or neural pacemakers, hydrocephalus shunts, kidney dysfunction with an eGFR ≤44 ml/min or on renal dialysis, intrauterine contraceptive device or a coil.

All patients provided full written informed consent. Ethical approval was granted by the North West Local Research Ethics Committee (10/H1005/12).

Imaging procedures

Contrast enhanced imaging was performed using a 1.5Tesla scanner (Phillips Gyroscan ACS NT (Phillips, Best, NL) at the NIHR Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Manchester. Immediately prior to imaging, patients had an intra-articular injection of the glenohumeral joint with 20 mls of 0.5% gadolinium in normal saline. All injections were performed under ultrasound guidance by specialist emergency clinicians. The MRA sequences taken were axial, sagittal and coronal obliques with T1 fat saturated (FS) imaging, proton density FS coronal oblique volume of the shoulder and Short Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) coronal oblique of the shoulder. These were scored for injury to bone and to all soft tissue structures including the glenoid labrum. All images were reviewed and scored by the study radiologist (CEH) who had 25 years of experience in musculoskeletal imaging and who was blinded to all other clinical data.

Outcome measures

The principle outcome measure for this pilot study was the presence and diagnosis of an identifiable injury, as determined by MRA. The specific lesions were lesions to any component of the rotator cuff, lesions to the glenoid labrum, the subacromial bursa, the capsule, the acromioclavicular joint and bony lesions such as bone marrow edema and fracture.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics only were calculated for this study. No formal sample size calculation was performed due to the feasibility nature of the project. Level of statistical significance was not required.

Results

A total of 26 patients were recruited during the study period. Their mean age was 44 years (Range 21–80) and there were four females.

Four patients who were unable to abduct their shoulder to 90° at first presentation had full active movement at the 2 week’s review clinic appointment. These patients were not included in the study and did not undergo MRA as the examining clinician was satisfied that they were recovering symptomatically and functionally. Of the remaining 22 eligible patients, one patient consented to the study but body habitus precluded MRA. Another patient initially agreed to take part in the study but withdrew on the day of the scan. Thus 20 patients were eventually scanned see Fig. 1; their characteristics and MRA diagnoses are shown in Table 1.

The clinical findings at initial presentation and at the review two weeks later are in Table 2. There were no adverse events during the scanning procedures. There were no a priori criteria for patients to have surgical repair. All patients with abnormal MRA were referred to a specialist shoulder surgeon for a further clinical review. Three of these eventually underwent a shoulder surgical procedure. Patient 1 had a hydrodilatation, patient 7 had a Bankart repair, and patient 8 had an arthroscopic labral repair and sub-acromial decompression.

Discussion

The findings in this pilot study are twofold. Firstly, as described in Table 1, there is a high incidence of significant soft tissue and bony pathology in patients presenting to an ED with acute shoulder injury who have normal plain radiographs. The significant injury may be identified by being unable to abduct to 90° at initial presentation in the ED with persistent significant active movement limitation at two week’s review. Secondly, four of these patients had injuries which needed surgical intervention. As such, the standard ED practice of discharging patients to primary care after an acute shoulder injury with a significant loss of active range of motion and a normal plain radiograph should be questioned.

This study was designed as an exploratory project to assess the potential impact of early investigation of shoulder injuries. We believe that our findings warrant further investigation. It is clear that requesting only plain film assessment for significant shoulder injury with very limited active abduction will miss a number of clinically important lesions. This represented the vast majority of patients in our cohort. This may be a result of imposing the relatively stringent definition of severe soft tissue injury as being unable to actively abduct to 90° at initial assessment and at 2 weeks. This particular inclusion criterion was based on the opinion of the study research team as an easy shoulder angle to assess accurately in clinical practice without a goniometer. The early diagnosis of a structural injury may be an indicator of patient outcome, but we were unable to conduct sufficiently long term follow up to determine whether spontaneous resolution of function occurred.

The results of the MRA were shared with participants and clinicians. This led to orthopaedic referral and physiotherapy intervention. Although we believe it likely that early referral and treatment would benefit patients compared to a delayed referral, this question cannot be addressed in this trial design.

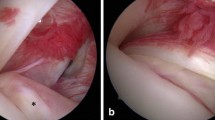

There are surprisingly little data in the literature on the role of advanced imaging techniques of the shoulder in the Emergency Department. As such, comparison with previous literature is difficult. This is the first attempt at early diagnosis with MRA of patients after acute shoulder trauma. Therefore the importance of diagnoses is important so that the patient can be appropriately referred for surgical or non-surgical management. This is emphasised by only one individual in our study having a normal MRA (Table 1 no. 5). One surprising finding was that four patients had fractures which were not visible on the plain film examination (e.g Fig. 2a and b; Fig. 3a, b, c and d). This highlights the usefulness of MR imaging to correctly diagnose these occult injuries and ensure the proper advice was given to patients regarding either mobilisation or rest. Nevertheless, we would urge some caution amongst Emergency Department clinicians who interpret our findings as suggesting all those who present with shoulder injuries should have an MRA. Our study’s aim was to use MRA to determine the pattern of underlying soft tissue injuries in patients with traumatic shoulder injury but who had a normal plain radiograph (e.g. Fig. 4a and b). The nature of our study also enabled us to see how MRA could be part of a decision making process. It is important to note that this does not exclude other decision making routes such as the effect on pain and impingement of a subacromial injection of local anaesthetic.

It might be argued that current ED management of shoulder acute injury is analogous to the knee joint twenty years ago. Historically patients with significant non-bony knee trauma such as anterior cruciate ligament ruptures were diagnosed in ED as ‘knee sprains’ and only investigated further if they had persistent problems, regular re-injury and re-presentation to ED. Currently, shoulder injuries follow a similar pathway. We believe that this study highlights the need to take these injuries in the shoulder more seriously and to investigate further whether early correct diagnosis, assessment and intervention improves patient outcome.

Conclusion

There is a high incidence of significant shoulder soft tissue injury definable on MRA amongst ED patients after trauma and an inability to actively abduct to 90° at initial presentation and two weeks later. Further work is required to determine whether early intervention will improve functional outcome in such patients.

References

Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(29):iii. 1-166

Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Takwoingi Y, Johnston RV, Hanchard NC, Faloppa F. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD009020.

Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, Morin A, Tamaddoni M, Moorman CT 3rd, Cook C. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(2):80–92. discussion 92

Hughes PC, Taylor NF, Green RA. Most clinical tests cannot accurately diagnose rotator cuff pathology: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(3):159–70.

Beaudreuil J, Nizard R, Thomas T, Peyre M, Liotard JP, Boileau P, Marc T, Dromard C, Steyer E, Bardin T, et al. Contribution of clinical tests to the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76(1):15–9.

Calvert E, Chambers GK, Regan W, Hawkins RH, Leith JM. Special physical examination tests for superior labrum anterior posterior shoulder tears are clinically limited and invalid: a diagnostic systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):558–63.

Jones GL, Galluch DB. Clinical assessment of superior glenoid labral lesions: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:45–51.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the study participants, colleagues in the ED at Manchester Royal Infirmary, the radiographers at the National Institute for Health Research, Biomedical Research Unit MR scanner at the NIHR Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Manchester.

Funding

Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust grant through the research for patient benefit fund (RfPB) R00713 and the National Institute for Health Research /Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Manchester, grant reference IMG-FRM-2. The funder had no role or influence in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MJC, SC, DH, CEH, JPB, DS for study conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. MJC SC, DH, CEH, JPB, DS for drafting the manuscript. MJC, SC, DH, JPB, CEH, DS gave final approval of the version to be published. MJC, SC, DH, JPB, CEH, DS take public responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the work. SC for acquisition of funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

North West Local Research Ethics Committee (10/H1005/12). All patients provided full written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Is not applicable, all radiological images and patient data are anonymised.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Callaghan, M.J., Baombe, J.P., Horner, D. et al. A prospective, observational cohort study of patients presenting to an emergency department with acute shoulder trauma: the Manchester emergency shoulder (MESH) project. BMC Emerg Med 17, 40 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-017-0149-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-017-0149-y