Abstract

Background

Acute arterial embolism due to tumor embolus is a rare complication in cancer patients, even rarer is lung tumor embolization leading to acute myocardial infarction. We report a patient who had a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction(AMI)which was brought on by a coronary artery embolism by a metastatic lung cancer tumor. Clinicians need to be aware that tumor embolism can result in AMI.

Case presentation

An 80-yeal-old male patient presented with persistent chest pain for 2 h and his electrocardiogram(ECG)showed anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Instead of implanting a stent, thrombus aspiration was performed. Pathological examination of coronary artery thrombosis showed that a few sporadic atypical epithelial cells were scattered in the thrombus-like tissue. Combined with immune phenotype and clinical history, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is more likely.

Conclusions

We report a rare case of a patient who was diagnosed of AMI due to a coronary artery embolism by a metastatic mass from lung cancer. Since there is no evidence-based protocol available for the treatment of isolated coronary thrombosis, we used thrombus aspiration to treat thrombosis rather than implanting a stent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is very common in clinics and usually caused by coronary plaque rupture, erosion, or nodules, however there are also unusual causes [1]. Coronary embolism(CE), a rare cause of AMI, refers to the entry of obstructive substances into coronary arteries, block their blood flow and result in ischemia. The incidence of AMI caused by CE is 2.9%. Acute arterial embolism caused by tumor embolism is a very uncommon complication in cancer patients [2], and AMI caused by pulmonary tumor embolism is even rarest. It has previously been reported that lung tumor embolism occurs in the coronary artery [3,4,5]. We report a case of AMI caused by lung cancer emboli.

Case presentation

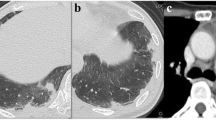

An 80-yeal-old male patient presented with persistent chest pain for 2 h and his electrocardiogram(ECG)showed anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (Fig. 1). Emergency coronary angiography was performed and the results showed the distal of the anterior descending was completely occluded and a significant amount of red and white thrombus was removed by using a thrombotic suction (Fig. 2A, B). The distal of the anterior descending was even and no obvious stenosis was observed and TIMI blood flow was grade 3, so we did not implant the stent. Echocardiography revealed normal overall left ventricular systolic function while there was no sign of a left ventricular thrombus or patent foramen ovale. The patient had a history of pulmonary space occupying for 1 year and we performed a histological examination of the thrombus. Pathological examination of coronary artery thrombosis showed that a small amount of atypical epithelial cells were scattered in the thrombus like tissue. Combined with immune phenotype and clinical history, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma is more likely. Immunohistochemistry results revealed that: A: AE1/AE3 (+), TTF-1 (-) P40 (+), CK7 (+), CK20 (-), Villin(-) (Fig. 3A, B)

Discussion

Left atrial myxoma, atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, malignancy, infective endocarditis, and atrial septal defect may cause CE induced AMI. Mert I Hayiroglu reported an 18-year-old boy who used marijuana was admitted to the hospital with severe substernal chest pain and coronary angiography revealed a considerable mid-segment blockage of the left anterior descending artery with a recent thrombus [6]. Mert İlker Hayıroğlu reported a 74-year-old man who was also experiencing dyspnea and excruciating chest discomfort arrived to the emergency room. The coronary angiography revealed that the proximal left anterior descending artery was completely blocked. Deep venous thrombosis was detected bilaterally by venous doppler ultrasonography. Biatrial thrombus development connected by the patent foramen ovale was detected by transthoracic echocardiography [7]. In our situation, the patient did not use any illicit drugs or materials, nor did he have any risk factors for coronary heart disease, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia or obesity. The incidence of CE in the left anterior descending branch, left circumflex branch, and right coronary artery dose not significantly differ, per the data that are now available [8]. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is generally used to acess the thromboembolism risk in non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients and Tufan evaluated its value in acute coronary syndromes [9]. However, more studies are requeired to further corroborate this.

Malignant tumors lead to venous or arterial thrombosis due to abnormal clotting, platelet activation, and endothelial dysfunction [10]. According to reports, 4.5% of patients develop venous thromboembolism and 1.5% experience arterial thromboembolism. Lung cancer is the most typical original malignant tumor that spreads to the heart [11]. Lung cancer invades the heart in two different ways: directly from the primary tumor or metastatic lymph nodes, and continuously through the pulmonary veins. Most arterial tumor embolism occurs during or shortly after pulmonary resection, rather than spontaneously as in this case [12]. To our knowledge, spontaneous global tumor embolism occurs in very few cases where the tumor invades the pulmonary veins of lung cancer, and the prognosis of most patients is poor [13, 14]. However, clinicians should be aware that tumor embolism is a potential cause of AMI. Acute arterial embolism caused by tumor embolus is a rare complication in tumor patients. Following the tumor nests’ invasion of the pulmonary veins, ejection from the body is the acknowledged mechanism of arterial embolization in malignant lung tumors [2]. In contrast to the right atrium and the two ventricles, the left atrium is anatomically a structure connected to the hilum of the lung by pulmonary veins, which explains why it is most frequently directly attacked by central lung tumors [15]. TTF-1 is expressed in 75-85% of lung adenocarcinoma, but not in squamous cell carcinoma, so it is mainly utilized to distinguish adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma. CK7 has a high sensitivity and is expressed in almost 100% of lung adenocarcinoma, but its specificity is poor and it is also expressed in 30–70% of lung squamous cell carcinoma, and P40 is basically not expressed in lung adenocarcinoma, but is expressed in more than 96.8% of squamous cell carcinoma. In our case, the patient had TTF-1 (-), CK7 (+), and P40 (+), so metastatic squamous cell carcinoma was highly likely [16].

Other arterial systems, such as the aorta, femoral artery, limb artery, and mesenteric artery, can also experience lung tumor embolism [17]. Aortic bifurcation or femoral vessels (50%) and cerebral circulation (30%) are the locations of tumor embolization that occur most frequently [18]. Advanced primary or metastatic lung cancers frequently pass via the pulmonary veins and reach the arterial system [19, 20].

Regarding the management of coronary embolization, there is currently no agreement. There are currently two therapies available for early ST-segment elevation AMI: intravenous thrombolysis and percutaneous intervention. For this kind of cardiac embolism, intravenous thrombolysis has been suggested in the literature [21,22,23,24]. Dual dose thrombolytic therapy has been demonstrated in certain studies to be superior to single dose therapy [25], however this is still up for debate. Thrombolytic therapy is not necessary if the dislodged embolus is an infected plant [26]. There have been reports of aspiration being used for intra-coronary embolization [27,28,29].

Conclusion

We described a rare case of a patient who had an AMI diagnosis brought on by a coronary artery embolism by a metastatic mass from lung cancer. Since there is no evidence-based protocol for the treatment of isolated coronary thrombosis we used thrombus aspiration to deal with thrombosis rather than implanting a stent. However, there was a flaw in our case because intravascular ultrasound(IVUS)or optical coherence tomography (OCT) were not to be used to evaluate the lesion’s susceptibility and composition.

Availability of data and materials

The data in this case report are not publicly available due to the privacy policies of the hospital but may be requested from the corresponding author if deemed reasonable.

Abbreviations

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CE:

-

Coronary embolism

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- IVUS:

-

Intravascular ultrasound

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

References

Higuma T, Soeda T, Abe N, et al. A combined optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound study on plaque rupture, plaque erosion, and calcified nodule in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction: incidence, morphologic characteristics, and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(9):1166–76.

Ohshima K, Tsujii Y, Sakai K, et al. Massive tumor embolism in the abdominal aorta from pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2017;67(9):467–71.

Kumagai N, Miura SI, Toyoshima H, et al. Acute myocardial infarction due to malignant neoplastic coronary embolus. J Cardiol Cases. 2010;2(3):e123–7.

Ackermann DM, Hyma BA, Edwards WD. Malignant neoplastic emboli to the coronary arteries: report of two cases and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1987;18(9):955–9.

Kushiyama S, Ikura Y, Iwai Y. Acute myocardial infarction caused by coronary tumour embolism. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(48):3690.

Hayiroglu MI, Kaya A, Avsar S, et al. Intracoronary thrombus in an 18-year-old teenager. Why?[J].Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi /. Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. 2016;22(4):396. https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj144439.

Acute myocardial infarction. With concomitant pulmonary embolism as a result of patent foramen ovale[J]. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(7):984e. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.12.025.

Shibata T, Kawakami S, Noguchi T, et al. Prevalence, clinical features, and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction attributable to coronary artery embolism. Circulation. 2015;132(4):241–50.

Tufan, Çınar et al. Mert Ilker Hayıroğlu, Veysel Ozan Tanık,. The predictive value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in patients with mechanical mitral valve thrombosis[J].Journal of Thrombosis & Thrombolysis, 2018.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-018-1640-3.

Mukai M, Oka T. Mechanism and management of cancer-associated thrombosis[J]. J Cardiol. 2018;72(2):89–93.

Anirban D, Das SK, Sudipta P, et al. Bronchogenic Carcinoma with Cardiac Invasion Simulating Acute Myocardial Infarction. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2016;2016:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7813509.

Isada LR, Salcedo EE, Homa DA, Cohen GI, Rice TW. Intraoperarive transesophageal echocardiographic localization of tumor embolus during pneumonectomy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5:551–4.

Navi BB, Kawaguchi K, Hriljac I, Lavi E, DeAngelis LM, Jamieson DG. Multifocal stroke from tumor emboli. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1174–5.

Clinical Outcomes of Acute Myocardial. Infarction patients with a history of malignant Tumor[J]. Vivo. 2020;34(6):3589–95.

Shimizu J, Ikeda C, Arano Y, et al. Advanced lung cancer invading the left atrium, treated with pneumonectomy combined with left atrium resection under cardiopulmonary bypass.[J]. Annals of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgery. 2010;16(16):286–90.

Carlo FD, Bernardi, Carlo MD et al. Lung cancer biopsy: Can diagnosis be changed after immunohistochemistry when the H&E-Based morphology corresponds to a specific tumor subtype?[J].Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil), 2018.https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2018/e361.

Chandler C. Malignant arterial tumor embolization. J Surg Oncol. 1993;52(3):197–202.

Whyte RI, Starkey TD, Orringer MB. Tumor emboli from lung neoplasms involving the pulmonary vein. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:421–5.

Ascione L, Granata G, Accadia M, Marasco G, Santangelo R, Tuccillo B. Ultrasonography in embolic stroke: the complementary role of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography in a case of systemic embolism by tumor invasion of the pulmonary veins in a patient with unknown malignancy involving the lung. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2004;5:304–7.

Imaizumi K, Murate T, Ohno J, Shimokata K. Cerebral infarction due to a spontaneous tumor embolus from lung cancer. Respiration. 1995;62:155–6.

Dogan M, Acikel S, Aksoy MM, et al. Coronary saddle embolism causing myocardial infarction in a patient with mechanical mitral valve prosthesis: treatment with thrombolytic therapy. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135:e47–8.

Steinwender C, Hofmann R, Hartenthaler B, et al. Resolution of a coronary embolus by intravenous application of bivalirudin. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:e115–6.

Atmaca Y, Ozdol C, Erol C. Coronary embolism in a patient with mitral valve prosthesis: successful management with tirofiban and half-dose tissue-type plasminogen activator. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:2321–2.

Quinn EG, Fergusson DJG. Coronary embolism following aortic and mitral valve replacement: successful management with abciximab and urokinase. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 2015;43(4):457–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199804)43:43.0.CO;2-F.

Hung WC, Wu CJ, Chen WJ, et al. Transradial intracoronary catheter-aspiration embolectomy for acute coronary embolism after mitral valve replacement. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30:316–8.

Aslam MS, Sanghi V, Hersh S, et al. Coronary artery saddle embolus and myocardial infarction in a patient with prosthetic mitral valve. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;57:367–70.

Fuster V, Chesebro JH, Frye RL, et al. Platelet survival and the development of coronary artery disease in the young adult: effects of cigarette smoking, strong family history and medical therapy. Circulation. 1981;63:546–51.

Belli G, Pezzano A, De Biase AM, et al. Adjunctive thrombus aspiration and mechanical protection from distal embolization in primary percutaneous intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;50:362–70.

Beran G, Lang I, Schreiber W, et al. Intracoronary thrombectomy with the X-sizer catheter system improves epicardial flow and accelerates ST-segment resolution in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Circulation. 2002;105:2355–60.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We thank for the financial support of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission and Shanghai Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine(ZXYXZ-201903).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YLZ performed the diagnostic coronary angiography for the patient and wrote the manuscript. MJM and YWW performed the pathological examination. BD and WZ, the co-corresponding authors, performed the percutaneous coronary intervention and wrote the manuscript. NZ,SZ,WKNK,LZ,XJS and ZYY prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We thank the patient for his approval and support in publishing this case report, a signed consent form is available to the Editors on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Mao, M., Zhang, N. et al. Acute myocardial infarction due to coronary embolism caused by a metastatic mass from lung cancer. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23, 461 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03505-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03505-3