Abstract

Background

Post cardiac injury syndrome (PCIS) is characterized by the development of pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion due to a recent cardiac injury. The relatively low incidence makes diagnosis of PCIS after implantation of a pacemaker easily be overlooked or underestimated. This report describes one typical case of PCIS.

Case presentation

We present a case report of a 94-year-old male with a history of sick sinus syndrome managed with a dual-chamber pacemaker who presented with PCIS after two months of pacemaker implantation. He gradually developed chest discomfort, weakness, tachycardia and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and cardiac tamponade after two months of pacemaker. Post-cardiac injury syndrome related to dual-chamber pacemaker implantation was considered based on exclusion of other possible causes of pericarditis. His therapy was drainage of pericardial fluid and managed with a combination of colchicine and support therapy. He was placed on long-term colchicine therapy to prevent any recurrences.

Conclusion

This case illustrated that PCIS can occur after minor myocardial injury, and that the possibility of PCIS should be considered if there is a history of possible cardiac insult.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Post cardiac injury syndrome (PCIS) is characterized by the development of pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion due to a recent cardiac injury. In addition to myocardial infarction, PCIS has been shown to be induced by pericardiotomy and blunt trauma, as well as by minor insults to the heart, such as coronary intervention, insertion of pacemaker leads, or radiofrequency ablation [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, since PCIS induced by insertion of a pacemaker or by coronary intervention is relatively uncommon, it is possible to miss this as an important differential diagnosis. Herein, we present a case of a 94-year-old male patient with a history of sick sinus syndrome treated with permanent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation, who displayed multiple symptoms of post-cardiac injury syndrome.

Case presentation

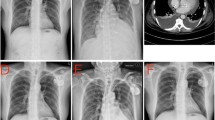

A 94-year-old Chinese Han male presented to the clinic with chief complaints of dyspnea, chest pain, and generalized weakness, the vital signs were BP 140/77 mmHg and HR 60 bpm on November 29, 2021. Previous history includes hypertension which treated by Hydrochlorothiazide, and prostate cancer which treated by Bicalutamide and Goserelin acetate. Surgical history includes sclerotherapy for varicose veins in the left leg ten years ago, and a permanent dual-chamber pacemaker (Medtronic A3DR01, the leads was active fixation and the ventricular catheter location was septal) that was implanted two months ago for sick sinus syndrome. Further examination is as follows: Arterial blood gas: PH 7.44, PCO2 28 mmHg, PO2 73 mmHg, K 4.4mmo1/L, Lac 0.6 mmol/L, HCO3- 19.0 mmol/L. Blood routine tests: WBC 6.52 × 109/L, Hb 111 g/L, PLT 230 × 109/L, NE% 77.9%. Liver and kidney function: ALT 60 IU/L, AST 71 IU/L, ALB 34.7 g/L, Scr 140.20umo1/L, eGFR 36.726 ml/min/1.73 m2 .Cardiac enzyme: CK-MB 3.5 ng/ml, hsTnI 140 ng/L, BNP 350 pg/ml. Coagulation: PT 13.4 s, APTT 34.8 s, FIB-C 4.87 g/L, D-D 3.03 mg/L. CRP 121 mg/L. PCT 0.11 ng/ml. The workup for infectious or autoimmune etiology, including TB-spot, HIV, herpes simplex virus (HSV), rapid plasma regains (RPR), echovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), fungal culture, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and rheumatoid factor was negative. The pacemaker showed normal function. Electrocardiograph (ECG): Pacemaker rhythm, no abnormalities compared to his ECG after pacemaker (Fig. 1). Chest X-ray: Multiple patchy high-density shadows in both lungs, enlarged heart shadow, blurred left costophrenic angle (Fig. 2). Chest CT: Large pericardium effusion, bilateral pleural effusion, partial expansion of both lungs, rule out perforation (Fig. 3). Echocardiogram: A large amount of pericardial effusion, diastolic collapse of right ventricle and right atrium, heart showed a swing sign, the inferior vena cava diameter widened (2.3 cm) and the difference of inspiratory retraction, left atrial enlargement (4.09 cm *5.54 cm *4.42 cm), EF 59%, PASP 48 mmHg (Fig. 4). Then he underwent low flow oxygen, intravenous Ceftriaxone (Rocephin), diuretic treatment, and pericardium puncture. His pericardium effusion was drainage 705 ml totally (Fig. 5, first 610 ml and second 95 ml). His pericardial histologic studies showed chronic inflammation with reactive changes, and they were negative for acid-fast bacilli and malignant cells. Cytology of pericardial fluid revealed hemorrhagic fluid (Hb 18 g/L) with nucleated cells (2756/mm3). Given his clinical manifestations on a background of unremarkable past medical history, and pacemaker implantation, circumstantial evidence raised suspicion for post cardiac injury syndrome. Tumor, tuberculosis or pacemaker lead perforation were excluded based on the above findings. As a result, he was started on a trial of colchicine 0.25 mg once a day, which he tolerated well without further recurrences of his symptoms. His follow up echocardiogram showed decreasing gradually pericardial effusion one month after discharge (Table 1).

Discussion

Post cardiac injury syndrome (PCIS) is characterized by the development of pericarditis with or without pericardial effusion due to a recent cardiac injury. The pathogenesis of PCIS is unclear, it may be an autoimmune process after heart injury, with antigens derived from damaged myocardial tissue.

Causes of PCIS include myocardial infarction, pericardiotomy, blunt trauma, and minor damage to the heart, such as coronary intervention, insertion of pacemaker leads, or radiofrequency ablation [1, 2]. Post-pacemaker insertion pericarditis is a rare type of PCIS that occurs in 1% to 2% of patients after pacemaker implantation [7]. Previous reports have shown that PCIS can occur within hours or days, or as early as 5–56 days after the procedure [8]. A patient’s medical history is essential for the recognize and diagnosis of PCIS, and patients undergoing the procedure should be followed up regularly from 1 to 3 months after the procedure [9]. The patient in our case is a 94-year-old male with a history of sick sinus syndrome managed with a dual-chamber pacemaker who presented with PCIS after two months of pacemaker implantation.

The mechanism of PCIS in general and post pacemaker insertion pericarditis in particular is still not well understood. Advanced age, female gender and the use of active fixation leads, a temporary transvenous pacemaker or steroid use are independent risk factors for the development of post pacemaker insertion pericarditis [10]. A proposed theory is that injury to mesothelial pericardial cells induces an immune response, leading to immune complex deposition in the pericardium, pleura, and lungs, which causes an inflammatory response [1, 7, 11]. The auto-immune nature of PCIS is supported by clinical features such as the latent period between the insult and symptoms, elevation of inflammatory markers, good response to NSAIDs, and a tendency to recur [4]. However, unlike other autoimmune diseases, circulating anti-cardiac antibodies are not detected until 14 days after the onset of PCIS, rather than at the initial diagnosis, and thus are not helpful in the diagnosis of PCIS [12].

The clinical manifestations of PCIS are pleurisy chest pain, fever, pericardial effusion and/or pleurisy with or without pleural effusion, and elevated reactants in the acute phase. Although almost all patients with PCIS have pericardial effusion, not all patients with pericardial effusion have symptoms or require treatment [10]. Distant heart sounds can be heard on physical examination, with signs of pericardial or pleural friction and pleural effusion. Chest imaging and echocardiography confirmed the presence of pleural and/or pericardial effusion and lead location. The diagnosis of post-cardiac injury syndrome after dual pacemaker implantation can only be diagnosed when other common infectious, autoimmune, or malignant causes have been excluded. An important differential diagnosis of PCIS is overt or minor lead perforation, which is also a common complication of pacemaker implantation [13]. There is no clear standard to distinguish pacemaker lead perforated from PCIS without perforation. Capture threshold increases, R wave amplitude decreases, lead impedance increases or decreases significantly, indicating lead perforation [6]. However, normal pacemaker function does not rule out the possibility of a perforated lead. In rare cases, lead perforation may be visible on imaging [7]. The patient in our case has typical symptoms and laboratory results consistent with the characteristics of PCIS, and was stable after 3 months of treatment according to the treatment regimen of PCIS. Reexamination of the UCG showed no increase in pericardial effusion, so the diagnosis of PCIS was considered.

The treatment of PCIS consists of similar treatment to other cases of acute pericarditis. The first-line therapy includes a combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine [8, 9, 14, 15]. Patients who do not tolerate NSAIDs and colchicine therapy or have a resolution of symptoms may be given a course of corticosteroids, which are tapered over weeks as the symptoms resolve [1, 9, 10, 16, 17]. If the patient develops pericardial effusion leading to cardiac tamponade, treatment with a pericardial window or surgical drainage may be necessary. Our patient showed adequate improvement with colchicine treatment and pericardium puncture though we reduced his colchicine dosage because of his advanced age. PCIS may be an immune process produced after heart injury, and attention to bed rest, avoid fatigue and strengthen nutritional support after heart injury may reduce the risk of PCIS.

Conclusions

Post pacemaker insertion pericarditis is a rare form of PCIS, and it usually presents within one month from pacemaker implantation with symptoms and signs of pericarditis. Diagnosis of PCIS is usually based on exclusion of other possible causes of pericarditis. Although PCIS responds well to NSAIDs and colchicine therapy, and has favorable prognosis, delayed diagnosis may result in potential serious complications such as cardiac tamponade. Therefore, its early detection is of clinical importance. Attention to bed rest after heart injury, avoid fatigue, strengthen nutritional support, may reduce the risk of incidence of PCIS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Imazio M, Hoit BD. Post-cardiac injury syndromes. an emerging cause of pericardial diseases [J]. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(2):648–52.

Bielsa S, Corral E, Bagüeste P, et al. Characteristics of pleural effusions in acute idiopathic pericarditis and post-cardiac injury syndrome [J]. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(2):298–300.

Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL. Pericarditis [J]. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):717–27.

Huang MS, Su YH, Chen JY. Post cardiac injury syndrome successfully treated with medications: a report of two cases [J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1):394.

Patel ZK, Shah MS, Bharucha R, et al. Post-cardiac injury syndrome following permanent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation [J]. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21737.

Ayan M. Pacemaker induced post cardiac injury syndrome [J]. MOJ Clin Med Case Rep. 2015;2(4):00028.

Wolk B, Dandes E, Martinez F, et al. Postcardiac injury syndrome following transvenous pacer or defibrillator insertion: CT imaging and review of the literature [J]. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013;42(4):141–8.

Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Imazio M, et al. International collaborative systematic review of controlled clinical trials on pharmacologic treatments for acute pericarditis and its recurrences [J]. Am Heart J. 2010;160:662–70.

Sedaghat-Hamedani F, Zitron E, Kayvanpour E, et al. Post cardiac injury syndrome after initially uncomplicated CRT-D implantation: a case report and a systematic review [J]. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103(10):781–9.

Ohlow MA, Lauer B, Brunelli M, et al. Incidence and predictors of pericardial effusion after permanent heart rhythm device implantation: prospective evaluation of 968 consecutive patients [J]. Circ J. 2013;77(4):975–81.

Imazio M, Brucato A, Rovere ME, et al. Contemporary features, risk factors, and prognosis of the post-pericardiotomy syndrome [J]. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(8):1183–7.

Hoffman M, Fried M, Jabareen F, et al. Anti-heart antibodies in postpericardiotomy syndrome: cause or epiphenomenon? A prospective, longitudinal pilot study [J]. Autoimmunity. 2002;35(4):241–5.

Banaszewski M, Stepinska J. Right heart perforation by pacemaker leads [J]. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8(1):11–3.

Tsai WC, Liou CT, Cheng CC, et al. Post-cardiac injury syndrome after permanent pacemaker implantation [J]. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2012;28:53–5.

Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the task force for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) [J]. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(42):2921–64.

Lazaros G, Sideris S, Antonopoulos A, et al. Incessant pericarditis following dual-chamber cardioverter defibrillation device implantation [J]. Int J Cardiol. 2016;212:184–6.

Imazio M, Lazaros G, Brucato A, et al. Recurrent pericarditis: new and emerging therapeutic options [J]. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13(2):99–105.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the geriatrics Department of Peking University First Hospital for their support.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the project 2019BD019 supported by PKU- Baidu Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: RZ; data collection: RZ, JD; data analysis and interpretation: RZ; drafting the article: RZ; critical revision of the article: JD, ML; final approval of the version to be published: RZ, JD, ML. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Patient’s identity is not disclosed anywhere, and IRB or ethics committee approval was not required to publish this work. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from individual participant included in the study to publish the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, R., Du, J. & Liu, M. Post-cardiac injury syndrome occurred two months after permanent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23, 259 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03252-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03252-5