Abstract

Background

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is an etiologically heterogeneous disorder. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of the underlying disease are of great significance. Herein, we present a rare case of MVP caused by anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA).

Case presentation

A 22-year-old female presented with a 16-year history of anterior mitral leaflet prolapse. However, she had never experienced any discomfort before. At a routine follow-up, a transthoracic echocardiogram showed anterior mitral leaflet prolapse (A2) with moderate mitral regurgitation, and a retrograde blood flow from an extremely dilated left coronary artery (LCA). Further coronary angiography and coronary computed tomography angiography confirmed the diagnosis of ALCAPA. She subsequently underwent successful LCA reimplantation and concomitant mitral valve replacement. Intraoperatively, her mitral annulus was mildly dilated, anterior mitral valve leaflet appeared markedly thickened with rolled edges, and a chordae tendineae connecting the anterior leaflet (A2) was ruptured and markedly shortened.

Conclusions

ALCAPA is a rare and potentially life-threatening congenital coronary artery anomaly that may cause mitral valve prolapse. Echocardiogram is an important screening tool for this disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is an etiologically heterogeneous disorder [1, 2]. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of the underlying disease are critical. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) is a rare and potentially life-threatening congenital coronary artery anomaly with an incidence of 1 in 300,000 live births, accounting for 0.25–0.5% of all congenital heart diseases [3]. Rarely, it is associated with other cardiac anomalies such as atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, aortic coarctation, tetralogy of Fallot or bicuspid aortic valve [4, 5]. Only 10% to 15% of ALCAPA patients develop significant collateral circulation from the right coronary artery (RCA) to the left coronary artery (LCA) and survive into adolescence or even adulthood with no or mild symptoms[6]. Nonetheless, collateral vessels are often insufficient to supply the entire left ventricle, resulting in ischemic dysfunction/impairment of the papillary muscles and adjacent myocardium, and ultimately mitral valve prolapse [5, 7]. Herein, we report an adult case with asymptomatic ALCAPA and anterior mitral leaflet prolapse, which was evaluated using multimodality imaging and then underwent successful reimplantation of the left coronary artery into the aorta and mitral valve replacement.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old female was referred to our out-patient clinic for follow-up on her asymptomatic mitral valve prolapse (MVP), which was discovered incidentally when she was 6 years old. She had never previously experienced dyspnea, chest pain or syncope. Physical examination revealed a grade 3/6 systolic murmur at the upper left sternal border. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with left anterior fascicular block and T wave inversion in leads I and aVL. All laboratory tests, including cardiac troponin, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) and autoantibodies, were unremarkable.

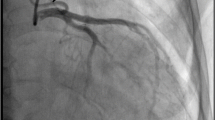

In addition to the anterior mitral leaflet prolapse (A2) with moderate mitral regurgitation and a mildly dilated left ventricle (left ventricular end-diastolic diameter: 56 mm) with a preserved ejection fraction (Fig. 1a and Additional file 1: Video 1), transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a retrograde blood flow from an extremely dilated left coronary artery (LCA) (Fig. 1b and Additional file 2: Video 2). Coronary angiography also revealed an enormously dilated and tortuous right coronary artery (RCA) originating from the right coronary cusp, with many collateral vessels filling the LCA (Additional file 3: Video 3), but failed to locate the orifice of LCA. Further coronary computed tomography angiography confirmed the diagnosis of ALCAPA (Fig. 2).

Given her high risk of left ventricular dysfunction, heart failure and malignant ventricular dysrhythmias, surgical correction was scheduled. Intraoperatively, her coronary arteries were found to be extremely dilated, the left ventricle and mitral annulus were mildly dilated, and anterior mitral leaflet appeared apparently thickened with rolled edges. More importantly, a chordae tendineae connecting the anterior leaflet (A2) was ruptured and markedly shortened (Fig. 3A–C). Therefore, reimplantation of the LCA into the aorta and concomitant mitral valve replacement were performed. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged from the hospital 2 weeks later. Three months following surgery, an echocardiogram revealed that her left ventricle had returned to normal (left ventricular end-diastolic diameter: 47 mm).

Discussion and conclusions

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome, is a rare and potentially life-threatening congenital coronary artery anomaly. It affects about 1 in every 300,000 live births, accounting for 0.25–0.5% of all congenital heart diseases [3]. Rarely, it is associated with other cardiac anomalies such as atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, aortic coarctation, tetralogy of Fallot or bicuspid aortic valve [4, 5]. Its manifestations and prognosis are strongly influenced by the magnitude of collateral vessels between the RCA and LCA. The overwhelming majority of patients with ALCAPA fail to develop significant collateral circulation from the RCA to the LCA during their early infancy period, and more than 90% of patients will suffer severe heart failure and ultimately die within the first year of life if left untreated. Only 10% to 15% of patients develop significant collateral circulation and survive into adolescence or even adulthood with no or mild symptoms [6]. Nevertheless, it is often insufficient to supply the whole left ventricle through collateral vessels, resulting in chronic myocardial ischemia. As a result, 80–90% of these patients may develop malignant ventricular dysrhythmias, the majority of which occur within the first 3 decades of life [5, 6]. In addition, they are at risk of developing silent myocardial infarction, left ventricular dysfunction and mitral insufficiency [5]. Our patient, who was also a young mother, had never experienced any discomforts in her life and her left ventricular function was preserved. This may have been attributed to her well-developed collateral vessels.

ALCAPA is most prevalent in infants, children and young adults. Therefore, this rare disorder may go unnoticed. Transthoracic echocardiogram, which is widely accessible, allows for a rapid and noninvasive assessment of structural and functional cardiac abnormalities at relatively low cost and is, therefore, the preferred imaging modality for these patients [8, 9]. In the present case, the extremely dilated coronary arteries and retrograde blood flow from the LCA shown by echocardiogram prompted us to search for the underlying cause of MVP. While coronary angiography allows for good visualization of the course of the anomalous coronary artery and collateral vessels, it is invasive and has some complications. Coronary computed tomography angiography, which has an excellent spatial and temporal resolution, can noninvasively show the origin and course of the anomalous coronary artery and it is regarded as the mainstay diagnostic technique for ALCAPA [10]. In addition, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a highly valuable imaging modality because of its unique tissue characterization, which enables the accurate assessment of myocardial ischemia and fibrosis [11, 12].

Prompt surgical intervention is critical for patients with ALCAPA, as it allows for gradual and even complete myocardial recovery [6, 13]. The recommended treatment for ALCAPA is direct reimplantation of LCA into the aorta to reestablish two-coronary circulation. In cases where direct reimplantation of LCA is not technically feasible (eg. LCA originating far from the aorta, abundant collaterals or noncompliant tissues around the ostium of ALCAPA), intrapulmonary tunnel repair (Takeuchi operation) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with LCA ligation should be considered [6, 14].

Mitral insufficiency (MR), a common complication of ALCAPA, is predominantly caused by ischemic dysfunction of the papillary muscles and adjacent myocardium, as well as annular dilation due to left ventricular remodeling [3, 15]. In these situations, the majority of mitral insufficiencies are reversible and may improve following ALCAPA repair, with only a small percentage deteriorating and requiring mitral valve reintervention [16]. Therefore, performing mitral valve intervention at the time of ALCAPA repair is still contentious. Nonetheless, structural abnormalities of the mitral apparatus including MVP, chordae tendineae rupture, mitral valve cleft and papillary muscle infarction/fibrosis, which occur in about 20% of ALCAPA patients, can’t recover from revascularization and concomitant mitral valve repair should be considered [3, 13, 16].

The mechanisms of MVP in ALCAPA may be similar to those in coronary artery disease, which include ischemic impairment of the papillary muscles and adjacent myocardium as well as chordae tendineae rupture [7, 17, 18]. Different from coronary artery disease, a recent study found that anterior leaflet prolapses occur more often in ALCAPA patients than posterior ones [16]. This may be explained by the difference in blood supply. For ALCAPA patients, the left ventricle is entirely supplied by the low-pressure collateral vessels. Additionally, the blood from collateral vessels preferentially flows into the low-pressure pulmonary circulation rather than into the high-resistance myocardial circulation, resulting in a longstanding “coronary steal” phenomenon. Lastly, the anterior papillary muscle is exclusively supplied by the remote branch of LCA [19]. In this case, the arterial supply of the anterior papillary muscle is severely compromised and the chordae tendineae connecting the anterior papillary muscle is highly vulnerable. Therefore, the ruptured chordae tendineae (A2) in our patient was probably caused by previously severe ischemic impairment. Furthermore, her anterolateral papillary muscle on the enhanced CT was much smaller than the posteromedial papillary muscle (Fig. 4), also indicating longstanding ischemic atrophy of the anterolateral papillary muscle.

In conclusion, ALCAPA is a rare and potentially life-threatening congenital coronary artery anomaly that may cause mitral valve prolapse. Echocardiogram is an important screening tool for this disorder.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALCAPA:

-

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery

- LCA:

-

Left coronary artery

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending artery

- AO:

-

Aorta

- MPA:

-

Main pulmonary artery

- RVOT:

-

Right ventricular outflow tract

- LCX:

-

Left circumflex

References

Althunayyan A, Petersen SE, Lloyd G, Bhattacharyya S. Mitral valve prolapse. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2019;17(1):43–51.

Delling FN, Vasan RS. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of mitral valve prolapse: new insights into disease progression, genetics, and molecular basis. Circulation. 2014;129(21):2158–70.

Kudumula V, Mehta C, Stumper O, Desai T, Chikermane A, Miller P, Dhillon R, Jones TJ, De Giovanni J, Brawn WJ, et al. Twenty-year outcome of anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: management of mitral regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(3):938–44.

Zhang Y, Wang B, Zhang L, Wang J, Li Y, Xie M. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and mitral valve cleft: a rare combination. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(12): e010731.

Pena E, Nguyen ET, Merchant N, Dennie C. ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease. Radiographics. 2009;29(2):553–65.

Yuan X, Li B, Sun H, Yang Y, Meng H, Xu L, Song Y, Xu J. Surgical outcome in adolescents and adults with anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(6):1860–7.

Hofmeyr L, Moolman J, Brice E, Weich H. An unusual presentation of an anomalous left coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) in an adult: anterior papillary muscle rupture causing severe mitral regurgitation. Echocardiography. 2009;26(4):474–7.

D’Anna C, Del Pasqua A, Chinali M, Esposito C, Iacomino M, Ciliberti P, Secinaro A, Carotti A, Rinelli G. Echocardiographic diagnosis of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from pulmonary artery with intramural course: a single-center study. JACC Cardiov Imag. 2021;15(6):1152.

Yang YL, Nanda NC, Wang XF, Xie MX, Lu Q, He L, Lu XF. Echocardiographic diagnosis of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Echocardiography. 2007;24(4):405–11.

Trevizan LLB, Nussbacher A, da Silva MCB, Ishikawa WY, de Oliveira SA, Sitta MDC, Szarf G. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery as a rare cause of left ventricular dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(12): e009724.

Mazine A, Fernandes IM, Haller C, Hickey EJ. Anomalous origins of the coronary arteries: current knowledge and future perspectives. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2019;34(5):543–51.

Latus H, Gummel K, Rupp S, Mueller M, Jux C, Kerst G, Akintuerk H, Bauer J, Schranz D, Apitz C. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of ventricular function and myocardial scarring before and early after repair of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:3.

Monge MC, Eltayeb O, Costello JM, Sarwark AE, Carr MR, Backer CL. Aortic implantation of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: long-term outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(1):154–60.

Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: collective review of surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(3):946–55.

Caspi J, Pettitt TW, Sperrazza C, Mulder T, Stopa A. Reimplantation of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery without mitral valve repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(2):619–23.

Weixler VHM, Zurakowski D, Baird CW, Guariento A, Piekarski B, Del Nido PJ, Emani S. Do patients with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery benefit from an early repair of the mitral valve? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;57(1):72–7.

Nappi F, Nenna A, Spadaccio C, Lusini M, Chello M, Fraldi M, Acar C. Predictive factors of long-term results following valve repair in ischemic mitral valve prolapse. Int J Cardiol. 2016;204:218–28.

Nappi F, Cristiano S, Nenna A, Chello M. Ischemic mitral valve prolapse. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(12):3752–61.

Rich NL, Khan YS (2022) Anatomy, thorax, heart papillary muscles. In: StatPearls Edn, Treasure Island.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WXF and LYC looked after the patient and wrote the report. LYC, XXR and LX performed the research and revised the report. HWY performed the coronary angiography and revised the report. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file1: Video 1 Echocardiogram showing anterior mitral leaflet prolapse with moderate mitral regurgitation and a mildly dilated left ventricle with a preserved ejection fraction.

Additional file 2: Video 2 Echocardiogram showing a retrograde blood flow from an extremely dilated left coronary artery.

Additional file 3: Video 3 Coronary angiography showing an enormously dilated and tortuous right coronary artery with many collateral vessels filling the left coronary artery.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Xia, X., Huang, W. et al. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery as a rare cause of mitral valve prolapse: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 22, 304 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02729-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02729-z