Abstract

Background

Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (SVA) is a rare congenital disease that can cause severe clinical presentations when the aneurysm ruptures. Here, we report a rare case of a noncoronary sinus of Valsalva aneurysm with rupture into the right atrium.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old Chinese female patient presented viral myocarditis with acute heart failure at the local hospital, and she was finally diagnosed with a noncoronary sinus Valsalva aneurysm with rupture into the right atrium by digital subtraction angiography with cardiac catheterization angiography and echocardiography at our hospital (Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University). Percutaneous closure intervention was performed shortly after her diagnosis, and the patient showed good functional recovery.

Conclusions

We report a case of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm successfully treated by percutaneous closure, which is an excellent alternative treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm (SVA) is a rare cardiac anomaly of the coronary sinuses caused by the absence of elastic tissue between the aorta and the annulus fibrosus [1]. The incidence of SVA accounts for 0.1–3.5% of congenital heart disease cases [2]. The mechanism of SVA involves deficiencies of muscle and elastic fibres in the middle layer, which progress into an aneurysm in the weakened area [3]. Patients who have SVA remain asymptomatic until one of the coronary sinuses ruptures into the cardiac chamber. According to previous reports, rupture of SVA usually occurs in adults, and the male:female sex ratio is 2–4:1 [4]. Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm most frequently originates from the right coronary sinus (70–90%), followed by the noncoronary sinus (10–25%) and, rarely, the left sinus (< 5%) [5]. SVA usually ruptures into the right ventricle (RV), then the right atrium (RA), and finally the left ventricle (LV) [6]. In this report, we present a rare case of noncoronary SVA rupture into the RA with acute heart failure.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old girl presented to the local hospital with vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea and was initially diagnosed with viral myocarditis, acute heart failure, and pneumonia. She was transferred to our department because her clinical symptoms had progressed to shortness of breath, chest tightness, fatigue, decreased activity, and white, foamy sputum. On physical examination, the girl was 49 kg in weight and 151 cm in height, her blood pressure was 127/71 mm·Hg, her heart rate was 125 bpm, her respiratory rate was 30 breaths per minute, and her transcutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 96%. Cardiac examination showed a normal S1 and S2 pulse, but a holosystolic murmur (grade 3/6) at the second left intercostal space.

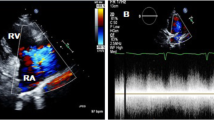

Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia and changes in the T wave. Chest X-ray displayed an enlarged cardiac silhouette (Fig. 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram (mid-aortic valve short-axis view demonstrated enlargement of the aortic sinus and a turbulent colour flow from the noncoronary sinus rupturing into the RA above the tricuspid valve (Fig. 2). In addition, transthoracic echocardiography also revealed enlargement of the cardiac chamber, aortic valve regurgitation (AR, mild, 2.5 mm), tricuspid regurgitation (TR, moderate, 3.6 mm), pulmonary hypertension (PH, moderate; flow rate of pulmonary valve regurgitation, 2.12 m/s; PASP≈53 mm·Hg), hydropericardium, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 71% and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) of 41%. Furthermore, transthoracic echocardiography was also used to measure the aortic dimensions, which are shown in Table 1.

Echocardiography with colour Doppler showing a high-velocity multicoloured (aliasing) mosaic of blood flow from the NCC to RA. The yellow arrow represents the shunt. NCS: noncoronary sinus; RCS: right coronary sinus; LCS: left coronary sinus; RA: right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA: left atrium; TV, tricuspid valve

Cardiac catheterization and aortic artery angiography (CAG) confirmed aortic valve prolapse (right coronary valve and noncoronary valve), a noncoronary SVA that had ruptured into the RA, and an obvious shunt (Fig. 3a). Next, the patient underwent percutaneous closure intervention. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia with CAG guidance. The pressure of the ascending aorta (AO) was 97 mm·Hg, and the pressure of the main pulmonary artery (MPA) was 34 mm·Hg, which was measured by CAG. The ruptured noncoronary SVA was measured at both the aortic end and the rupture site on angiography. The diameter at the rupture site was 7.8 mm, and a 12 mm Amplatzer duct occluder (Shanghai Shape Memory Alloy Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) was selected for closure. The closure device could be seen clearly, and there was no shunt from the aortic valve to the RA (Fig. 3b). Postoperative echocardiography showed that there was a highlighted echo representing the closure device, and there was no shunt from the aorta to the cardiac chamber, with an LVEF of 58% and an LVFS of 31% (Fig. 4a). The reason for the postprocedural reduction in LV function may have been hyperdynamics before the percutaneous closure intervention. At the same time, the aortic dimensions were also measured, as shown in Table 1. Echocardiography with a 3D imaging view of the aortic root showed the closure device (Fig. 4b). The patient was discharged on postoperative Day 12 with an uneventful recovery.

a Echocardiography with colour Doppler showing the closure device, and there was no shunt from the aorta to the cardiac chamber; b Echocardiography with a 3D imaging view of the aortic root showed the closure device. LCS, left coronary sinus; NCS, noncoronary sinus; RCS, right coronary sinus; RA: right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA: left atrium

Discussion and conclusions

SVA, which was first reported by Edwards in 1957, can be divided into congenital or acquired [7]. The mechanism of SVA is dysplasia of sinus tissue during the embryonic period; an SVA ruptures when an acute event, such as infective endocarditis, intense activity, or some other stressor, occurs [8]. It was reported that congenital SVA is usually associated with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, and other tissue disorders. However, acquired SVA is frequently associated with atherosclerosis, infective endocarditis, trauma, and other factors [9]. Our patient was considered to have congenital SVA due to a lack of family history and tissue disorder screening. The patient received a genetic test for Marfan syndrome, but the result was negative.

According to the literature, SVA is usually asymptomatic in the paediatric age range and is seldom diagnosed unless it is ruptured or associated with any other severe complicated syndrome [10]. In addition, it has been reported that most SVA patients are diagnosed within a mean age range from 30 to 45 years [11]. SVA usually occurs in the right coronary sinus (approximately 70% of cases), then the noncoronary sinus (approximately 25% of cases), and finally the left coronary sinus if ruptured, and there is often rupture into the RV and RA [12]. Furthermore, Wang et al. [13] reported the same results when comparing the incidence rate of SVA between Asians and Westerners (aneurysms arising from the right coronary sinus in 86% vs. 67.8%, respectively). Therefore, our patient was diagnosed with an even rarer case of a noncoronary SVA ruptured into the RA, which is worth reporting and discussing.

The diagnosis of SVA depends on imaging tools such as echocardiography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CAG. Echocardiography is usually the initial diagnostic tool because of its noninvasive, low-cost, real-time, accurate evaluation of the dynamic anatomical structure, haemodynamics, and cardiac function, including the diagnosis of cardiac valve stenosis, anomaly, and valve prolapse. Regarding newer approaches, we found that CTA can show sinus origination and shunting more accurately than echocardiography can, but CTA is less helpful for intravascular blood flow assessment, is easily influenced by the heart rate and poses the risks of ionizing radiation and allergy. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a potential supplementary approach but is expensive and easily influenced by the heart rate. CAG is the gold standard for the diagnosis of SVA [14]; it can not only define the anatomy of the coronary sinus and clarify the change in haemodynamics but can also readily guide percutaneous closure intervention for SVA.

The patient in our case was diagnosed with noncoronary SVA ruptured into the RA, with a large shunt from the aorta to the RA. She was asymptomatic before being referred to the hospital with a common cold. We infer that she was affected by a congenital SVA that ruptured due to the infection. Echocardiography diagnosed the rupture of SVA first, and she received the percutaneous closure intervention immediately with good recovery. Compared to surgery, percutaneous closure intervention has the advantages of noninvasiveness and a quicker recovery with occlusive devices [15], and it may be an excellent alternative treatment for SVA. However, it should be noted that percutaneous closure intervention may also incur complications such as residual shunt, AR and TR; fortunately, after receiving the percutaneous closure intervention, our patient showed no shunt, along with mild AR and mild TR, thereby demonstrating good recovery.

In conclusion, we report a case of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm successfully treated by percutaneous closure, which is an excellent alternative treatment for SVA.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data could be contacted for Kunfeng Jiang who is the first author of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- SVA:

-

Sinus of Valsalva aneurysm

- RV:

-

Right ventricle

- RA:

-

Right atrium

- LV:

-

Left ventricle

- AR:

-

Aortic valve regurgitation

- TR:

-

Tricuspid regurgitation

- PH:

-

Pulmonary hypertension

- AO:

-

Ascending aorta

- MPA:

-

Main pulmonary artery

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVFS:

-

Left ventricular fractional shortening

- CTA:

-

Computed tomographic angiography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CAG:

-

Cardiac catheterization and angiography

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

References

Kumar V, Jose J, Joseph G. Rupture of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm into the left ventricle after dissecting through the interventricular septum mimicking aortic regurgitation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2016;105:560–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-015-0947-8.

Feldman DN, Roman MJ. Aneurysms of the sinuses of Valsalva. Cardiology. 2006;106:73–81.

Weinreich M, Yu PJ, Trost B. Sinus of Valsalva aneurysms: review of the literature and an update on management. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38:185–9.

Zhang T, Juan C, Yuan G, Zhang H. Giant unruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: a rare one arise from left sinus. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12: e009850. https://doi.org/10.1161/circimaging.119.009850.

Moustafa S, Mookadam F, Cooper L, Adam G, Zehr K, Stulak J, et al. Sinus of Valsalva aneurysms—47 years of a single center experience and systematic overview of published reports. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1159–64.

Singh SM, Rohit T, Rajiv G, Singh WG. A case report: a rare case of severe aortic incompetence

Edwards JE, Burchell HB. The pathological anatomy of deficiencies between the aortic root and the heart, including aortic sinus aneurysms. Thorax. 1957;12:125–39.

Luo XJ, Li X, Peng B, Guo HW, Hu SS. Modified Sakakibara classification system for ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm. Chin J Clin Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:874–8.

Zhixia S, Jiantao G, Hui W, et al. Aortic sinus aneurysm rupture into the right atrium in a 29-year-old patient. J Clin Ultrasound. 2017;47:319–21.

Amano T, Naganuma T, Nakamura S. Stabilized sinus of Valsalva aneurysm after corevalve implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:103–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.10.011.

Lee JH, Yang JH, Park PW, Song J, Huh J, Kang IS, et al. Surgical repair of a sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: a 22-year single-center experience. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;69:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692660.

Liu L, Wan Y, Deng MB. Giant aneurysmal of the left sinus of Valsalva in adults. J Cardiac Surg. 2020;35:3145–7.

Wang ZJ, Zou CW, Li DC, Li HX, Wang AB, Yuan GD, et al. Surgical repair of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm in Asian patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:156–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.022.

Yang K, Luo X, Tang Y, Hu H, Sun H. Comparison of clinical results between percutaneous closure and surgical repair of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Intervent. 2020;97:354–61.

Morais H, Ferreira H, Nelumba T. Surgical treatment versus percutaneous closure of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: a systematic review and meta-analysis; 2021.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by Project of Chongqing Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau (cx2019065).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KFJ wrote the report, performed the literature research and took the pictures. JYC and XZ wrote a part of the report and performed the literature research. HX and TTR analyzed the data and controlled it. YT and XJJ revised the report, and are the corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, K., Chen, J., Zhu, X. et al. Rupture of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: a case report in a child. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 22, 158 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02603-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02603-y