Abstract

Background

Women with atrial fibrillation (AF) experience greater symptomatology, worse quality of life, and have a higher risk of stroke as compared to men, but are less likely to receive rhythm control treatment. Whether these differences exist in elderly patients with AF, and whether sex modifies the effectiveness of rhythm versus rate control therapy has not been assessed.

Methods

We studied 135,850 men and 139,767 women aged ≥ 75 years diagnosed with AF in the MarketScan Medicare database between 2007 and 2015. Anticoagulant use was defined as use of warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant. Rate control was defined as use of rate control medication or atrioventricular node ablation. Rhythm control was defined by use of anti-arrhythmic medication, catheter ablation or cardioversion. We used multivariable Poisson and Cox regression models to estimate the association of sex with treatment strategy and to determine whether the association of treatment strategy with adverse outcomes (bleeding, heart failure and stroke) differed by sex.

Results

At the time of AF, women were on average (SD) 83.8 (5.6) years old and men 82.5 (5.2) years, respectively. Compared to men, women were less likely to receive an anticoagulant or rhythm control treatment. Rhythm control (vs. rate) was associated with a greater risk for heart failure with a significantly stronger association in women (HR women = 1.41, 95% CI 1.34–1.49; HR men = 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.28, p < 0.0001 for interaction). No sex differences were observed for the association of treatment strategy with the risk of bleeding or stroke.

Conclusion

Sex differences exist in the treatment of AF among patients aged 75 years and older. Women are less likely to receive an anticoagulant and rhythm control treatment. Women were also at a greater risk of experiencing heart failure as compared to men, when treated with rhythm control strategies for AF. Efforts are needed to enhance use AF therapies among women. Future studies will need to delve into the mechanisms underlying these differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia prevalent in adults over 65 years of age, with a twofold increase in prevalence every decade of life beyond 50 years [1]. Sex differences exist in the incidence of AF, with women having a lower incidence of AF compared to men [2, 3]. However, women with AF experience greater symptomatology, functional impairment and worse quality of life compared to their male counterparts [4, 5]. Women with AF also have a higher risk of stroke (more evident at age over 65 years), and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as compared to men [6,7,8]. Despite their higher symptom burden and stroke risk, women with AF are less likely to (1) be seen by a cardiologist, (2) receive rhythm control treatment, including cardioversion and AF ablation, and (3) be prescribed appropriate anticoagulation [5, 9,10,11,12]. However, little is known about potential sex differences in the use of specific treatment strategies and adverse outcomes among the elderly (aged 75 years and older). This is particularly relevant given the higher risk of stroke and other complications among this group and the pervasive nature of health inequities between men and women, even at older ages [13, 14].

This study aims to explore the association of biological sex with treatment of AF and outcomes among men and women over 75 years with claims for AF in the IBM MarketScan database. Our primary aim is to estimate potential sex differences in the initiation of AF treatments, specifically anticoagulant therapy and rate versus rhythm control strategy, among newly diagnosed patients with AF. Secondarily, we aim to evaluate the association of sex with cardiovascular (stroke and heart failure hospitalization) and major bleeding outcomes as well as the interaction between sex and treatment strategy with regard to these outcomes. We hypothesized that women were less likely to receive anticoagulation than men and, among those receiving anticoagulation, more women would initiate anticoagulation on warfarin [vs. direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)] as compared to men. We also hypothesized sex interactions in the associations of anticoagulant use and rate control treatment with outcomes, with women on these therapies experiencing greater adverse health outcomes as compared to men with a similar risk factor profile.

Methods

Study population

We used data from the IBM MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare) Database (IBM Watson Health) from January 1, 2007 through October 1, 2015. The MarketScan Medicare database contains individual level healthcare claims and enrollment data from individuals and their dependents with Medicare supplemental plans within the United States [15]. The database contains claims for inpatient and outpatient services, as well as outpatient pharmacy claims.

In the present analysis, the study population consisted of participants enrolled in the MarketScan database at some point between January 1, 2007 and October 1, 2015, who were continuously enrolled for 180 days prior to receiving a diagnosis of non-valvular AF. Valvular AF, defined in this analysis as AF with a history of mitral stenosis (ICD-9-CM 394.0) or mitral valve disorder (ICD-9-CM 424.0), is a contraindication for DOACs and, in general, has a different management and has been excluded from this analysis. AF was diagnosed using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, 427.31 and 427.32 for one inpatient or two outpatient claims between 7 days and a year apart, in any position [16]. The final study sample consisted of 275,617 men and women (Fig. 1).

Treatment strategy

Oral anticoagulant use (warfarin and DOACs) within 30 days after the initial diagnosis of AF was assessed from outpatient pharmacy claims. Oral anticoagulant use claims were included independent of the dose prescribed, assuming patients were prescribed the correct dosage, to create a binary variable for anticoagulant use. Previously, it has been shown that the validity of warfarin claims in administrative databases has a high positive predictive value of 99% [17].

Rate and rhythm control treatment strategies within 30 days after the initial diagnosis of AF were ascertained from pharmacy, inpatient and outpatient claims. Rate control was defined as receipt of any of the following treatments: beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, digoxin or atrioventricular node ablation procedure (CPT code 93650) without a pacemaker. Rhythm control was defined by the presence of any of the following: receipt of antiarrhythmic medication, catheter ablation procedure (CPT code 93651 (before 2013), 93656 or 93657 (after January 2013) or ICD-9-CM procedure code 37.34 in the absence of codes for pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator implementation, or AV node ablation) and cardioversion (ICD-9-CM code 99.61, 99.62, or CPT code 92960, 92961). Participants who received both rate and rhythm control treatment were classified under rhythm control.

Outcome events

The outcome variables were initial hospitalization for a major bleeding episode, heart failure and ischemic stroke, after a diagnosis of AF. These outcomes were identified from the primary diagnosis of hospitalizations using ICD-9-CM codes and applying validated algorithms [18,19,20]. Specific codes used to define each outcome are provided in Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Sex and other covariates

Sex was determined at entry into the MarketScan database by patient-level demographic information and defined as male and female. Co-morbidities and medication use determined a priori to be risk factors for these outcomes were identified using ICD-9-CM codes from inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims prior to the time of diagnosis of AF, using previously developed algorithms [21]: age at diagnosis, excessive alcohol consumption, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, stroke, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease, gastrointestinal bleed, disorders of the liver, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, depression, intracranial and other bleeds. Claims data were also used to obtain information on prevalent medication at the time of AF diagnosis: lipid lowering medication, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, gastrointestinal medication, other cardiac medication, potassium supplements, cardiac glycosides, antidiabetics, antiplatelets, thiazide diuretics, antiarrhythmics, insulin, sulphonylureas, other diuretics, statins, digoxin and angiotensin receptor blockers.

Statistical analysis

Poisson regression with robust error variance was used to estimate the relative risk for the association between sex and initial treatment strategy within 30-days post diagnosis of AF. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the association of treatment, post-AF diagnosis with time to an initial hospitalization of each of the outcomes (stroke, major bleeding and heart failure). Each outcome was fit in a separate Cox model. Treatment was determined by what participants received in the 30-day period after a diagnosis of AF, with follow-up time to the outcome beginning at that 30-day mark, thus excluding those who did not start treatment or who died during this time frame. In all models, we adjusted for age initially and then for all the other risk factors and medications listed above. We tested for both multiplicative and additive (through assessment of the interaction contrast ratio) interaction of treatment choice with sex and also fit sex-stratified Cox proportional hazard models for each outcome. All analyses were run on SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Participant characteristics

The characteristics of the study population at the time of AF diagnosis (N = 275,617), stratified by sex are represented in Table 1. The average age (SD) of the population was 83.2 (5.4) years. Women were slightly older than men (83.8 vs. 82.5, respectively). Women were more likely to have hypertension, dementia or depression. They were also more likely to be prescribed calcium channel blockers and digoxin. Men were more likely to have a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease and hyperlipidemia. They were also more likely to be prescribed anticoagulants, anti-platelet medication, anti-arrhythmic drugs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and statins.

Association of sex with choice of treatment strategy

Overall 26.3% women received an anticoagulant during the 30 days after diagnosis, as did 27.7% of men. Women were slightly less likely to receive an anticoagulant (vs. none) within 30-days post diagnosis of AF after adjusting for age, cardiovascular risk factors and relevant medication [relative risk (RR) 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.93, 0.96] (Table 2). Among OAC users, 18.7% of women and 18.2% of men used a DOAC. After adjustment, among those receiving oral anticoagulation, women had a slightly higher probability of receiving DOACs (vs. warfarin) (RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01, 1.08). Rhythm control (vs. rate control) treatment was less common in women than in men after adjustment for age (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.83, 0.86) and other risk factors (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.93, 0.96).

Sex, anticoagulation and adverse outcomes

Among male AF patients, those receiving any anticoagulant (as compared to those not on an anticoagulant) had a higher hazard of incident heart failure [hazard ratio (HR) 1.17, 95% CI 1.11, 1.22] and major bleeding (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.18, 1.30) and a lower hazard of stroke (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78, 0.90), after adjusting for age (Table 3). Similar results were seen after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors. Women on any anticoagulant (vs. no anticoagulant) also had a higher hazard of heart failure [1.26 (1.20, 1.31)] and major bleeding [1.29 (1.23, 1.36)] and a lower hazard for stroke [0.91 (0.86, 0.97)], after adjusting for age and similarly after adjustment for other risk factors. We identified a significant multiplicative interaction between sex and anticoagulant initiation in relationship to heart failure hospitalization, with the risk of heart failure associated with oral anticoagulation being stronger in women than men. On the additive scale, we found positive additive interaction for sex and anticoagulation in relation to each of the three adverse outcomes (interaction contrast ratio (ICR) of 0.076 for heart failure, 0.068 for stroke and 0.056 for major bleeding episodes) (Table 3).

We evaluated the association of the use of DOACs (compared to warfarin) with outcomes (Table 4). Participants on DOAC had a lower hazard of heart failure (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.73, 0.91 in men and HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.73, 0.92 in women) after adjusting for age. Associations were attenuated after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors. Analyses did not provide evidence of differences in stroke or bleeding risk by type of oral anticoagulant between men and women on the multiplicative scale. However, on the additive scale, we found evidence of a positive additive interaction for sex and DOAC usage in relation to bleeding (ICR = 0.063), stroke (ICR = 0.119) and heart failure hospitalization (ICR = 0.02).

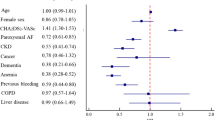

Sex, rhythm versus rate control therapy, and adverse outcomes

We assessed the association of rhythm control strategy (compared to rate control) with adverse outcomes (Table 5). In men, rhythm control was associated with a greater risk for heart failure (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.14, 1.25) and a lower risk for ischemic stroke (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.67, 0.80). There was no evidence of meaningful association of rhythm (vs. rate) control therapy with the risk of major bleeding (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.98, 1.10). These results were seen in the age-adjusted model. Among women, we saw similar results with slightly larger point estimates. Women on any rhythm control had a higher hazard of heart failure (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.28, 1.40) and a lower hazard of ischemic stroke (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.75, 0.87) than those on rate control therapy. There was no association between rhythm (vs. rate control) and an episode of major bleeding (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.95, 1.07), after adjusting for age. There was a significant multiplicative interaction between sex and treatment, with the association of rhythm (vs. rate) control therapy with heart failure risk being stronger in women than men. Also, there was a positive additive interaction between sex and use of rhythm (vs. rate) control treatment for the risk for stroke and heart failure. There was a negative additive interaction for sex and rhythm control (v. rate) and bleeding, but the magnitude of this interaction was small (− 0.03).

Discussion

This study found, in a healthcare claims database, treatment of AF and the association between treatment choice and outcomes among elderly patients with AF differed by sex. Elderly patients with AF represent a unique clinical situation with a high prevalence of polypharmacy and multiple comorbidities that may alter or limit the use of specific therapies. Characterizing potential sex disparities in treatment and outcomes of AF can identify gaps in care and could be key to improve outcomes among this patient group. Specifically, we found that elderly women are less likely than men to be prescribed an anticoagulant or receive rhythm control treatment after a diagnosis of AF. Participants with a diagnosis of AF receiving an anticoagulant were at a higher risk for heart failure and a major bleeding episode but at a lower risk for an ischemic stroke. Within anticoagulants, DOACs were associated with lower risk of heart failure (vs. warfarin), but not of stroke or bleeding. Rhythm control (vs. rate control) was associated with an increased risk for heart failure and a lower risk for ischemic stroke. The associations of anticoagulant therapy and rhythm control with heart failure was significantly stronger in women compared to men.

Sex differences in AF treatment

Our study found that women aged ≥ 75 years were less likely to be prescribed an oral anticoagulant compared to men. This finding is consistent with some previous studies [9, 22]. In the Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation, men with AF, aged ≥ 75 years and the presence of > 1 stroke risk factor were significantly more likely to receive warfarin as compared to women with a similar risk profile (44.9% vs. 24.5%) [23]. Similarly, in the PINNACLE National Cardiovascular Data Registry, women were less likely to use an OAC than men, overall and at all levels of the CHA2DS2-VASc score [24]. The PINNACLE study also found that DOAC use was increasing among women in the study [24].

Considering differences in use of OACs across a broader age-range, contrary to our findings, data from more recent observational cohort, registry and administrative studies appear to suggest that there is less evidence in support of the existence of sex disparities in use of OAC’s for atrial fibrillation [4, 25,26,27,28]. In the Euro Observational Research Programme on Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) Pilot survey, among men and women aged > 65 years, a greater number of women received oral anticoagulation after an AF diagnosis (women vs. men, 95.3 vs. 76.2%) [25]. In the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) study, there were similar rates of anticoagulation among men and women [4]. The change in observed sex differences in anticoagulation could be related to the inclusion of the CHA2DS2-VASc score in guideline-based management for AF [29]. This score includes female sex as a risk factor for thromboembolic events and may have led to more women with AF receiving an OAC. Adoption of these guidelines could also have led to a decrease in the observed differences in OAC use between men and women.

As in our analysis, other studies have found that women are less likely than men to receive rhythm control therapy as compared to rate control [4, 22, 25,26,27,28, 30]. Among women receiving anti-arrhythmic therapy, they were also less likely to receive AV-node ablation or cardioversion [22, 31]. This has been attributed to the perception of prescribers that biological differences between men and women could lead to worse health outcomes in women. Women require higher doses of AV nodal agents to address the greater noradrenergic reponse seen in them [32, 33]. Women also tend to have a longer baseline QTc interval (secondary to sex hormone levels) than men, which makes them more susceptible to developing torsades de pointes on certain class III and class Ia anti-arrhythmics [34, 35].

Oral anticoagulation and adverse outcomes

In this study we found that men and women on any anticoagulant were at a slightly higher risk for heart failure, particularly among women, and a major bleeding episode and at a lower risk for ischemic stroke. The observed increased risk of heart failure among those receiving anticoagulation, particularly women, is unexpected, and could be explained by residual confounding or this could be a chance finding.

DOACs versus warfarin and outcomes

When comparing the effect of DOAC (vs. warfarin) on outcomes, we found DOACs were associated with lower risk of heart failure in both men and women. A recent study found that DOACs, compared to warfarin, were associated with a lower risk for intracranial hemorrhage and all-cause mortality in women with no difference in the risk for stroke, systemic embolism and gastrointestinal bleeds [36]. Similarly, in a registry-based analysis from Japan on patients with AF on DOAC’s, despite women in the study having a higher bleeding risk, there was no meaningful difference in bleeding episodes but they did experience a higher risk for thromboembolic events [37]. Among participants on DOACs, other studies have found lower risk for a major bleeding episode among women [38, 39] while men experienced lower risk of stroke and systemic embolism [39]. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing DOACs to warfarin confirmed these findings [40]. In this study we did not see a lower risk of major bleeding when on DOACs, which may be related to residual confounding, or specific to this older age population.

Rhythm versus rate control and adverse outcomes

This study found that rhythm control (vs. rate control) strategies were associated with a higher risk for heart failure, a lower risk for stroke and had no effect on major bleeding episodes in both men and women. The association of rhythm control with heart failure risk was slightly stronger in women than men. Some of our results concur with observations from landmark clinical trials. The AFFIRM trial, conducted in an elderly population (mean age 75 years), found no difference in the risk of stroke or major bleeding with rate control (vs. rhythm control) [41]. The ORBIT-AF registry study, also conducted in the elderly (mean age 74 years) found in the unadjusted analyses that rhythm control was associated with a lower risk for stroke, major bleeding and CV mortality, these results did not stay the same when adjusting for risk factors [42]. A post-hoc analysis of the AFFIRM study [43], RECORD-AF [44] and observational data [45] found that long-term rhythm control lowered mortality and hospitalization. The increased risk in heart failure in our study on rhythm control may be related to the age of our participants and the presence of multiple co-morbidities at baseline predisposing them to the adverse effects of anti-arrhythmic drugs and other rhythm control approaches. Among women, a higher risk for HF in AF may be related to treatment strategy which is in turn related to healthcare provider (generalist vs. specialist) and perhaps a longer lifespan which could allow for a longer time to development of HF in AF. We also noted a lower risk for stroke with rhythm control in the MarketScan population, perhaps pointing to adequate anticoagulation among those receiving rhythm control or residual confounding.

Strengths and limitations

Our results should be interpreted considering the study limitations. Our primary concern is uncontrolled confounding: we did not have detailed clinical data, such as symptom burden, type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, permanent), heart rate, or presence of hemodynamic instability at time of diagnosis, that could help inform treatment decisions and provide information on prescribing patterns. We used diagnostic codes for all variables in the analysis and potential for misclassification exists. Where possible, however, we used validated algorithms to minimize this misclassification.

Our study also has several strengths. The claims data we used is geographically diverse, containing data from Medicare enrollees (with supplemental insurance) from across the United States. We had access to risk factor information, allowing for adjustment and the study of effect modification in our analysis. Due to the comprehensive nature of the database, we had a large study sample size of participants aged 75 years and older. Database enrollment and censoring due to disenrollment are unlikely to be related to exposures and endpoints, limiting the risk of selection bias.

In conclusion, this study identified sex differences in treatment of elderly patients with AF as well as response to such treatments. We found that elderly women were less likely to receive any anticoagulation or rhythm control as compared to men. While both men and women on anticoagulants and/or rhythm control had an increased risk for heart failure, women had a modestly higher risk. This study adds to the body of evidence highlighting the importance of understanding sex differences in treatment and outcomes in an elderly population with atrial fibrillation and with a high prevalence of co-morbidities and polypharmacy. Future studies will need to delve into determinants of prescribing patterns and underlying mechanisms to understand the basis of these sex differences and develop strategies to resolve them.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in the current analysis cannot be deposited in a public repository due to licensing and privacy restrictions. Access to this data was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Individuals interested in obtaining the MarketScan data used in the current analysis should contact IBM Watson Health using the contact form provided at https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases/databases.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DOAC’s:

-

Direct oral anticoagulants

- AV:

-

Atrioventricular

References

Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271(11):840–4.

Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Chamberlain AM, Prineas RJ, et al. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African–Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2009;158(1):111–7.

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–5.

Piccini JP, Simon DN, Steinberg BA, Thomas L, Allen LA, Fonarow GC, et al. Differences in clinical and functional outcomes of atrial fibrillation in women and men: 2-year results from the ORBIT-AF registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):282–91.

Lip GY, Laroche C, Boriani G, Cimaglia P, Dan G-A, Santini M, et al. Sex-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Observational Research Programme Pilot survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Ep Europace. 2014;17(1):24–31.

Friberg J, Scharling H, Gadsbøll N, Truelsen T, Jensen GB. Comparison of the impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of stroke and cardiovascular death in women versus men (The Copenhagen City Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(7):889–94.

O'Neal TW, Alam AB, Sandesara PB, J'Neka SC, MacLehose RF, Chen LY, et al. Sex and racial differences in cardiovascular disease risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. bioRxiv. 2019:610352.

Marzona I, Proietti M, Farcomeni A, Romiti GF, Romanazzi I, Raparelli V, et al. Sex differences in stroke and major adverse clinical events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 993,600 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2018;269:182–91.

Hsu JC, Maddox TM, Kennedy K, Katz DF, Marzec LN, Lubitz SA, et al. Aspirin instead of oral anticoagulant prescription in atrial fibrillation patients at risk for stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(25):2913–23.

Shantsila E, Wolff A, Lip G, Lane D. Gender differences in stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in general practice: using the GRASP-AF audit tool. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(8):840–5.

Avgil Tsadok M, Jackevicius CA, Rahme E, Humphries KH, Pilote L. Sex differences in dabigatran use, safety, and effectiveness in a population-based cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Quality Outcomes. 2015;8(6):593–9.

O’Neal WT, Sandesara PB, Claxton JS, MacLehose RF, Chen LY, Bengtson LGS, et al. Influence of sociodemographic factors and provider specialty on anticoagulation prescription fill patterns and outcomes in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(3):388–94.

Li S, Fonarow GC, Mukamal KJ, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Smith EE, et al. Sex and race/ethnicity-related disparities in care and outcomes after hospitalization for coronary artery disease among older adults. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(2 Suppl 1):S36-44.

Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Song J, Chang RW. Gender and ethnic/racial disparities in health care utilization among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(4):S221–33.

Adamson DM, Chang S, Hansen LG. Health research data for the real world: the MarketScan databases. New York: Thompson Healthcare; 2008. p. b28.

Claxton JS, MacLehose RF, Lutsey PL, Norby FL, Chen LY, O’Neal WT, et al. A new model to predict major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation using warfarin or direct oral anticoagulants. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203599.

Garg RK, Glazer NL, Wiggins KL, Newton KM, Thacker EL, Smith NL, et al. Ascertainment of warfarin and aspirin use by medical record review compared with automated pharmacy data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(3):313–6.

Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Saczynski JS, Dodd KS, et al. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):100–28.

Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA. An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(6):560–6.

Saczynski JS, Andrade SE, Harrold LR, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Dodd KS, et al. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying heart failure using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):129–40.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9.

Kassim NA, Althouse AD, Qin D, Leef G, Saba S. Gender differences in management and clinical outcomes of atrial fibrillation patients. J Cardiol. 2017;69(1):195–200.

Humphries KH, Kerr CR, Connolly SJ, Klein G, Boone JA, Green M, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation: sex differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome. Circulation. 2001;103(19):2365–70.

Thompson LE, Maddox TM, Lei L, Grunwald GK, Bradley SM, Peterson PN, et al. Sex differences in the use of oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR((R))) PINNACLE Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7):e005801.

Lip GY, Laroche C, Boriani G, Cimaglia P, Dan GA, Santini M, et al. Sex-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Observational Research Programme Pilot survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Cardiac Electrophysiol J Work Groups Cardiac Pacing Arrhythm Cardiac Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2015;17(1):24–31.

Potpara TS, Marinkovic JM, Polovina MM, Stankovic GR, Seferovic PM, Ostojic MC, et al. Gender-related differences in presentation, treatment and long-term outcome in patients with first-diagnosed atrial fibrillation and structurally normal heart: the Belgrade atrial fibrillation study. Int J Cardiol. 2012;161(1):39–44.

Bhave PD, Lu X, Girotra S, Kamel H, Vaughan Sarrazin MS. Race- and sex-related differences in care for patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(7):1406–12.

Li YM, Jiang C, He L, Li XX, Hou XX, Chang SS, et al. Sex Differences in presentation, quality of life, and treatment in Chinese atrial fibrillation patients: insights from the China Atrial Fibrillation Registry Study. Med Sci Monitor Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2019;25:8011–8.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–104.

Dagres N, Nieuwlaat R, Vardas PE, Andresen D, Levy S, Cobbe S, et al. Gender-related differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation in Europe: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(5):572–7.

Zylla MM, Brachmann J, Lewalter T, Hoffmann E, Kuck KH, Andresen D, et al. Sex-related outcome of atrial fibrillation ablation: insights from the German Ablation Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(9):1837–44.

Luzier AB, Killian A, Wilton JH, Wilson MF, Forrest A, Kazierad DJ. Gender-related effects on metoprolol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66(6):594–601.

Mitoff PR, Gam D, Ivanov J, Al-hesayen A, Azevedo ER, Newton GE, et al. Cardiac-specific sympathetic activation in men and women with and without heart failure. Heart. 2011;97(5):382–7.

Pratt CM, Camm AJ, Cooper W, Friedman PL, MacNeil DJ, Moulton KM, et al. Mortality in the Survival With ORal D-sotalol (SWORD) trial: why did patients die? Am J Cardiol. 1998;81(7):869–76.

Torp-Pedersen C, Moller M, Bloch-Thomsen PE, Kober L, Sandoe E, Egstrup K, et al. Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(12):857–65.

Law SWY, Lau WCY, Wong ICK, Lip GYH, Mok MT, Siu CW, et al. Sex-based differences in outcomes of oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(3):271–82.

Matsumura M, Sotomi Y, Hirata A, Sakata Y, Hirayama A, Higuchi Y. Sex-related difference in bleeding and thromboembolic risks in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with direct oral anticoagulants. Heart Vessels. 2021:1–9.

Pancholy SB, Sharma PS, Pancholy DS, Patel TM, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Meta-analysis of gender differences in residual stroke risk and major bleeding in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with oral anticoagulants. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(3):485–90.

Proietti M, Cheli P, Basili S, Mazurek M, Lip GY. Balancing thromboembolic and bleeding risk with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs): a systematic review and meta-analysis on gender differences. Pharmacol Res. 2017;117:274–82.

Raccah BH, Perlman A, Zwas DR, Hochberg-Klein S, Masarwa R, Muszkat M, et al. Gender differences in efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(11):1135–42.

Shariff N, Desai RV, Patel K, Ahmed MI, Fonarow GC, Rich MW, et al. Rate-control versus rhythm-control strategies and outcomes in septuagenarians with atrial fibrillation. Am J Med. 2013;126(10):887–93.

Noheria A, Shrader P, Piccini JP, Fonarow GC, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, et al. Rhythm control versus rate control and clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: results from the ORBIT-AF Registry. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;2(2):221–9.

Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Geller N, Greene HL, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1509–13.

Camm AJ, Breithardt G, Crijns H, Dorian P, Kowey P, Le Heuzey JY, et al. Real-life observations of clinical outcomes with rhythm- and rate-control therapies for atrial fibrillation RECORDAF (Registry on Cardiac Rhythm Disorders Assessing the Control of Atrial Fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(5):493–501.

Ionescu-Ittu R, Abrahamowicz M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Wynant W, et al. Comparative effectiveness of rhythm control versus rate control drug treatment effect on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(13):997–1004.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R21AG058445, K24HL148521, and R01HL122200, and by American Heart Association grant 16EIA2641001 (Alonso). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funder had no role in the design of the study; the analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation or review of the manuscript and, decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS wrote the main manuscript. VS performed analysis with input from JSC. AA and VS designed the analysis. AA provided critical feedback in all stages of analysis and manuscript preparation. AA, JSC, PLL, RFM, LYC, AMC and FLN provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved of it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Deidentified data generated by IBM MarketScan was made available for analysis, per licensing agreements. Emory University IRB approved this project with a waiver of informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no known competing interests as outlined by BMC.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanya, V., Claxton, J.S., Lutsey, P.L. et al. Sex differences in treatment strategy and adverse outcomes among patients 75 and older with atrial fibrillation in the MarketScan database. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02419-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02419-2