Abstract

Background

As the most frequent type of cyanotic congenital heart disease (CHD), tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) has a relatively poor prognosis without corrective surgery. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) represent a novel class of endogenous noncoding RNAs that regulate target gene expression posttranscriptionally in heart development. Here, we investigated the potential role of the ceRNA network in the pathogenesis of TOF.

Methods

To identify circRNA expression profiles in TOF, microarrays were used to screen the differentially expressed circRNAs between 3 TOF and 3 control human myocardial tissue samples. Then, a dysregulated circRNA-associated ceRNA network was constructed using the established multistep screening strategy.

Results

In summary, a total of 276 differentially expressed circRNAs were identified, including 214 upregulated and 62 downregulated circRNAs in TOF samples. By constructing the circRNA-associated ceRNA network based on bioinformatics data, a total of 19 circRNAs, 9 miRNAs, and 34 mRNAs were further screened. Moreover, by enlarging the sample size, the qPCR results validated the positive correlations between hsa_circ_0007798 and HIF1A.

Conclusions

The findings in this study provide a comprehensive understanding of the ceRNA network involved in TOF biology, such as the hsa_circ_0007798/miR-199b-5p/HIF1A signalling axis, and may offer candidate diagnostic biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets for TOF. In addition, we propose that the ceRNA network regulates TOF progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital malformation, consisting of structural and functional abnormalities of the cardiovascular system that develop during the embryonic period and are present at birth. CHD affects 0.5–0.8% of all live births and is the leading cause of neonatal death [1,2,3]. According to the changes in cardiac haemodynamics and pathophysiology, CHD can be divided into two main categories: cyanosis and nonmagnetic form. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common type of cyanotic congenital heart disease, accounting for 7–10% of all common CHDs [4, 5]. TOF consists of a ventricular septal defect (VSD), pulmonary stenosis, right ventricular hypertrophy, and aorta overriding the ventricular septum. With surgical correction progressing in recent years since the initial successful repair of TOF, the attention of the research community has shifted towards understanding causation [1, 6]. However, the exact pathogenesis of TOF remains elusive. Numerous studies have shown that miRNA expression should be disordered in TOF heart tissues [7]. To date, there have been few relevant reports on the comprehensive profiling of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) in TOF hearts.

Current knowledge and understanding have shown that temporal and spatial expression patterns of heart development-related genes are essential in the regulation of cardiomyogenesis, which means that both genetic and epigenetic factors play a crucial role throughout development [8, 9]. Abnormal functional connectivity in the regulation network leads to failure of cardiac cell lineage specification, commitment, and differentiation [10, 11]. Unfortunately, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain relatively poorly understood. Using next-generation sequencing technology, increasing evidence supports the deregulation of ncRNAs in the dysregulation of cardiomyogenesis [12, 13]. Different types of ncRNAs include microRNAs and a variety of long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), such as lncRNAs, antisense RNAs, pseudogenes, and circular RNAs (circRNAs). For circRNAs, using a high-throughput circRNA microarray is beneficial for detecting and studying circRNAs compared with circRNA-seq [14]. However, microarray can only explore known circRNAs. To identify novel circRNAs, next-generation sequencing technology is a suitably sensitive tool.

Recently, circRNAs, as hot topics and trends in scientific research, have provided further opportunities for better understanding the biological mechanisms of heart diseases [15, 16]. CircRNAs, as closed structures, are evolutionally conserved, tissue-specific, and relatively stable. In addition, accumulating integrative analyses have demonstrated that circRNAs are involved in regulating gene transcription and biological processes by acting as miRNA “sponges”, competing for endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), including RNA transcripts, miRNAs, and circRNAs. All of the observed characteristic features give circRNAs obvious advantages in the exploration of new clinical diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [17]. However, there have been only a few reports exploring circRNAs in human TOF, even though an enrichment for various diseases/functions of these promising circRNA findings was identified.

In the present study, we performed microarray analysis and evaluated circRNA expression profiles in heart samples from healthy controls and foetuses with TOF. Moreover, by using bioinformatics analysis of these differentially expressed circRNAs, we screened key circRNAs and constructed a ceRNA network. Our results may contribute to a mechanistic understanding of the pathogenesis and the identification of potential therapeutic targets for TOF in the future.

Methods

Participants

All microarray analyses were run on samples from 3 foetuses with nonsyndromic TOF (i.e., no 22q11.2 deletion) and 3 normally developing hearts of foetuses that were ultimately aborted. Additionally, we recruited an additional 20 subjects (10 nonsyndromic TOF patients and 10 healthy controls) to expand the sample size in the independent validation via qPCR.

We obtained foetal hearts (at approximately 150 days of gestation) from the Fujian Provincial Maternity and Children’s Hospital (approval number: IRB NO. 2019–046). The foetal hearts were dissected by a surgeon who also performed many of the reconstructions of the conotruncal defects (Hua Cao) to ensure that the analysed myocardial tissue samples were all taken from a similar location (right ventricle outflow tract) [18]. After each sample was removed, the bloodstains were washed with precooled physiological saline, and the sample was then immediately stored in RNAlater at − 80 °C for subsequent processing.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA content was extracted from the tissues using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative expression levels of mRNA and circRNA (normalized to β-actin) were analysed by the 2−ΔCt relative quantification method, and the relative circRNA expression was calculated with the 2−ΔCt method [19]. qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green qPCR kit (TOYOBO, Tokyo, Japan) in the StepOne PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Profiling of circRNA expression by the Arraystar Human Circular RNA V2.0

The Arraystar Human Circular RNA Microarray V2.0 (Arraystar, Inc.), performed by Kang Chen Biotech (Shanghai, China), was designed for the purpose of profiling circRNAs in the human genome. Scanned image processing was analysed using Agilent Feature Extraction Software Version 11.0.1.1. CircRNAs (|fold-change|≥ 2.0 and P-value < 0.05) were selected as markedly differentially expressed circRNAs. The microarray data produced in this study have been uploaded to the NCBI/GEO repository (Accession Number: GSE145610).

Construction of the ceRNA (circRNA-miRNA-mRNA) regulatory network

Several online bioinformatics platforms were used in conjunction to predict circRNA-miRNA-target gene associations. The targeted miRNAs and corresponding miRNA response elements of circRNAs were first obtained by utilizing a homemade miRNA target prediction tool derived from Arraystar. In addition, we extracted differentially expressed DE miRNAs from GSE35490, which included 16 TOF and 8 healthy control samples[18]. Target genes of integrated miRNAs were detected by targetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), miRTar-Base (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu. edu.tw/php/index.php) and miRDB (http://mirdb.org/) [20]. The circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network was constructed utilizing the integration of circRNA-miRNA pairs and miRNA-mRNA pairs. Finally, the regulatory network of TOF was visualized using the R package “ggalluvial” [21].

Functional enrichment analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses of genes involved in the ceRNA network were performed using the database for integrated discovery bioinformatics resources (Enrichr, http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/enrich) [22]. Genes involved in the ceRNA network that were more relevant to CHD were identified. The comparative toxicogenomics database (http://ctdbase.org/) was used to integrate chemical-gene, chemical-disease, and gene-disease interactions to predict novel associations and generate expanded networks [23]. The relationships between gene products and congenital heart defects were analysed through these data. Here, relationships between genes extracted from the ceRNA network and diseases are shown in a radar chart.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All statistical data were analysed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) 23.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons between different groups were performed using independent Student’s t-test (two-tailed) or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test [24]. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to identify the relationships between circRNAs and mRNAs [25]. In all cases, a P-value < 0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant difference.

Results

Screening of differentially expressed circRNAs

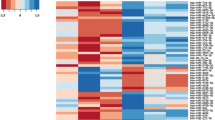

We performed Arraystar Human circRNA Array analysis to identify TOF-related circRNAs. Box plots were constructed to show the distribution of circRNA expression profiles. After normalization, the distribution of log2 ratios across different samples is displayed in Fig. 1a. We then used a scatterplot to identify differentially expressed circRNAs between the TOF group and the control group (Fig. 1b). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis revealed a deregulated circRNA expression pattern in clinical samples (Fig. 1c).

Overview of circRNA expression profiles. a A box plot was used to compare the distributions of circRNA expression values for TOF heart tissues and normal heart tissues (control) after normalization. b Scatter-plot representing variations in circRNA expression between the TOF group and control group (log2 scaled). c Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of dysregulated circRNA expression among samples. The colour scale shows the relative expression levels of circRNAs across different samples

The general data, including the functional classifications and chromosome locations of these differentially expressed circRNAs, were summarized. Overall, 276 circRNAs were found to be significantly differentially expressed (|logFC|-value > 2.0, P-value < 0.05) (Additional file 1: Table 1). Compared to the control group, 214 circRNAs, including 183 exonic, 13 intronic, 16 sense overlapping, 1 antisense, and 1 intergenic circRNA, were upregulated, and 62 circRNAs, including 53 exonic, 3 intronic, 5 sense overlapping, and 1 antisense circRNA, were downregulated in the CHD group (Fig. 2a, b). As demonstrated in Fig. 2c and d, the up- and downregulated circRNAs were located on human chromosomes.

Annotation of differentially expressed circRNAs in TOF heart tissues. (a, b) Classification of dysregulated circRNAs. “Exonic” represents a circRNA arising from the exons of a linear transcript; “Intronic” represents a circRNA arising from an intron of a linear transcript; “antisense” represents a circRNA whose gene locus overlaps with the linear RNA but is transcribed from the opposite strand; “sense overlapping” represents circRNA originating from the same gene locus as the linear transcript. c The locations of upregulated circRNAs in human chromosomes. d The locations of downregulated circRNAs in human chromosomes

The circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network in TOF

A total of 793 miRNA response elements (MREs) of the differentially expressed circRNAs were identified by utilizing the miRNA target prediction tool derived from Arraystar (Fig. 3a). Next, to consolidate the identified MREs that are associated with TOF and screen the more significant miRNAs, we used GSE35490 from the NCBI/GEO database to screen 123 differentially expressed miRNAs in the TOF group compared with the healthy groups (|logFC|-value > 1.5, P value < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). Using Venn diagram analysis, 25 shared miRNAs (key miRNA signature) were obtained and are presented in the Venn diagram (Fig. 3c).

Identification of a 25 miRNA-based signature. a Results of target prediction and sequence analyses of microRNA response elements (MREs). The 2D structure shows the MRE sequence and the corresponding target miRNA seed type. b The volcano plot indicates the differentially expressed miRNAs obtained from GSE35490. The vertical lines correspond to 1.5-fold up and down, respectively, and the horizontal line across the screen represents P = 0.05. c The Venn diagram shows the numbers of key miRNA signatures

To predict the key target mRNAs, we further uploaded the abovementioned 25 key miRNAs to the miRDB, miRTarBase, and TargetScan databases for searching. Thirty-four key mRNAs that interacted with 8 of the 25 key miRNAs in all 3 datasets were selected. After removing the remaining 17 key miRNAs and the corresponding circRNAs, 19 circRNAs, 8 miRNAs, and 34 mRNAs were ultimately obtained to construct the ceRNA network related to TOF (Fig. 4; Additional file 2: Table 2).

Functional GO terms and pathway enrichment analyses

To characterize the functional consequences of our identified genes, we performed an enrichment analysis of the ChIP-X (ChEA) database with Enrichr for all 34 key genes involved in the ceRNA network. The results revealed that the GO term with the most statistical significance was heart development (P-value = 0.002538) (Fig. 5a).

GO enrichment and pathway analyses of the key genes involved in the ceRNA network. a The top 9 significantly enriched functional GO terms retrieved using Enrichr. b Radar diagram depicting the relationships of congenital heart defects related to the key genes based on the CTD database. c Unsupervised clustering of samples based on the expression levels of the key genes

In addition, we characterized the putative pathogenic genes of TOF based on the CTD database. A total of 34 genes had curated or inferred associations with congenital heart defects ranked by inference score. Among these genes, HIF1A was the most significant marker gene (Fig. 5b), as confirmed by three studies [11, 26, 27]. To make our results more reliable, we further assessed the association of 34 genes with TOF using the public database GSE35776 [28]. Unsupervised clustering resulted in two distinct subgroups according to the gene expression model (Fig. 5c).

Upregulation of hsa_circ_0007798 expression in TOF heart tissues

To validate the previous study results, we expanded the sample size. The expression levels of hsa_circ_0007798 in 10 TOF heart tissues and 10 healthy heart tissues were measured by qPCR, which revealed that hsa_circ_0007798 expression was significantly upregulated in the TOF group (P < 0.001, Fig. 6a). By inquiring from circBase (http://www.circbase.org), we knew that hsa_circ_0007798 is located on chromosome 6 and is composed of 6 exons containing the full 805-bp sequence (Fig. 6b). According to ceRNA theory, circRNAs mostly act by competitively sponging miRNAs to regulate the expression of their target genes. Therefore, based on our screening strategy, we first considered hsa_circ_0007798/miR-199b-5p/HIF1A (Fig. 6c). In addition, the results of the qPCR correlation analysis verified the positive linear relationship between hsa_circ_0007798 and HIF1A (Pearson r coefficient = 0.6291) (Fig. 6d). These results could make it possible for us to understand how predicted and screened key circRNA-miRNA-mRNA relationships are related to TOF progression.

Functional hsa_circ_0007798/miR-199b-5p/HIF1A regulatory module. a Validation of the differential expression of hsa_circ_0007798. The expression level was analysed using qPCR (TOF: n = 10, Control: n = 10). b, c Predicted miRNAs targeting hsa_circ_0007798 based on a homemade tool derived from Arraystar’s software. d Validation of the relationship between hsa_circ_0007798 and HIF1A. The horizontal axis represents the expression of the mRNA, and the vertical axis indicates the expression of the circRNA

Discussion

It is well known that cardiac development is a dynamic and complex process. At the same time, cardiac development is finely regulated by the body itself, and minor developmental disorders (such as genetic or environmental factors) are sufficient to cause severe cardiac defects and subsequent embryonic or foetal death. TOF, as one of the most common cyanotic congenital heart diseases in the world, is estimated to account for 7%–10% of CHD cases [37] and is the result of the intersection of genetic, apparent, and environmental risk factors [27]. Studies have shown that rare extracardiac lesions in CNV and syndromic TOF may affect the reproductive suitability and propagation pattern of TOF [38], such as the 22q11.2 deletion and the associated 22q11.2 deletion syndrome [39]. Like other types of CHD, the exact cause of TOF is unclear. At present, with the help of new auxiliary treatment equipment, most children with TOF undergoing corrective surgical repair can survive to adulthood, but the long-term course of postoperative residual lesions in some children may still eventually lead to right ventricular dysfunction, ventricular arrhythmia and advanced sudden cardiac death [40, 41], which assumes a long-term economic burden on families and society. Studies have shown that TOF can occur in other noncardiac (syndromic) or isolated (nonsyndromic) environments. Among them, syndrome-type TOF accounts for approximately 20% of cases; it is mainly associated with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11del), and its clinical outcome has a worse prognosis [42, 43]. In a large study involving nine institutions, the most frequent harmful mutation in adults and infants with TOF was the NOTCH1 mutation, which is estimated to account for 4.5% of nonsyndromic TOF cases. The next most common harmful mutation site was FLT4, which accounted for 2.4% of cases. In addition, previously involved heart transcription factors (such as TBX1, NKX2.5, GATA4, HAND2, and GATA6, etc.) leading to pathogenic mutations exist in only 1.2% of the population [44], and the lack of efficient biomarkers and the unclear mechanisms underlying TOF are still challenges in the field of cardiology [5, 6, 27].

Previous research has demonstrated that genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, including mutation, histone modification, DNA/RNA methylation, ncRNA modifications and others, play vital roles in cardiac development [8, 12, 18]. Among these major events, ncRNAs may be potential biomarkers for better prognosis and diagnosis. However, research into circRNAs is just beginning. Studies have found that circRNAs are produced by reverse splicing of the precursor mRNA (pre mRNA) of exons of thousands of genes in eukaryotes, in which the downstream 50 splice site (Ss) is linked to the upstream 30 Ss, and the resulting RNA loop is linked by a 30–50 phosphodiester bond at the linkage site[46, 47]. As early as 25 years ago, researchers found only a few circRNAs, which were generally considered aberrant splicing by-products with little functional potential[45, 49]. circRNAs are more stable than linear ribonucleic acids because circRNAs lack a free end, and their cyclic structures prevent degradation by nucleic acid exonuclease[48].

Rapid advances in biochemical methods and the use of high-throughput sequencing technology in recent years have served to isolate and identify a wider range of circRNAs [51]. Genome-wide analysis showed that most of the circRNAs were abundant and conserved across species, displaying cell type-, tissue-, and developmental stage-specific expression patterns in eukaryotic cells, indicating that circRNAs played a vital role in the regulation of transcriptomics and biological processes, including heart-related diseases [29,30,31].

Studies have shown that circRNAs are linked to the physiological and pathological development of many organisms, while some circRNAs are related to neuronal function, congenital immune response, cell proliferation, and pluripotency [53]. It has been found that circRNAs have various functions. At the molecular level, they participate in gene expression by isolating microRNA or protein, regulating RNA polymerase II (POL II) transcription, processing pre-interfering mRNA, and translating the resulting polypeptides [50]. Increasing evidence shows that circRNAs, as the binding sites for sponge RNAs and miRNAs competing for miRNAs, maintain RNA-binding protein and control the expression of alternative splicing and parental genes, indicating that cyclic RNA is becoming an important regulatory element at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level [32, 52]. At present, competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) is a new field of RNA biology that implicates a large-scale regulatory network among multiple types of RNA (circRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs) at the transcription level [17]. A study has shown that circRNAs derived from PWWP2A can serve as endogenous miR-223 sponges to inhibit myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure [54]. The myocardial infarction-related circRNA (MICRA) level was found to be a robust predictor of LV dysfunction 3–4 months after myocardial infarction [55].

To date, this study is the first to provide systematic profiling of circRNA expression in TOF and to investigate further characterization of the role of the ceRNA network in the pathogenesis of TOF in the early life stage. Moreover, we identified and screened 214 significantly upregulated and 62 downregulated circRNAs through microarray analysis. Then, 19 circRNAs were chosen according to the established multistep screening strategy, and the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory module was constructed in an attempt to better explore TOF occurrence and development. We analysed the functions and pathways of key mRNAs participating in the ceRNA network using ChIP-X (ChEA) and the CTD database. These key mRNAs were mainly enriched in functions of “heart development” and “NOTCH signalling pathway”, which are closely associated with TOF [8]. In addition, we found that HIF1A is closely linked to human CHD, consistent with previous studies [33]. Studies have suggested that metabolic cardiac remodelling is associated with HIF1A deficiency and maternal diabetic exposure. The combination of diabetic pregnancy and HIF1A deficiency changes vascular homeostasis in the myocardium due to maternal diabetes and increases the risk of cardiovascular abnormalities in offspring [56]. In addition, reduced Nkx2-5 expression together with a sustained hypoxia-inducible factor 1α response led to embryo death [57].

This study has demonstrated that circRNAs can affect the occurrence and development of heart disease and cardiovascular disease, have potential as diagnostic or predictive biomarkers of disease, and offer new potential therapeutic targets. we rescreened the most promising ceRNA module by targeting HIF1A and performed correlation analysis to reveal that hsa_circ_0007798 has the positive correlation with HIF1A. Among the module, miR-199b-5p serves as a bridge between the circRNA and the mRNA. Coincidentally, miR-199b-5p was identified to participate in left ventricular remodeling, associated with pathologic cardiac hypertrophy [35,36,37]. These studies are in accordance with our finding showing hsa_circ_0007798/miR-199b-5p/HIF1A regulatory module is associated with the cardiac defects, including the TOF. However, compared with encoded RNAs and other noncoding RNAs (miRNAs and lncRNAs), our current understanding of circRNAs still has a significant gap, and the expression of circRNAs in human TOF myocardial tissue has not yet been reported. In this study, the Arraystar human circRNA chip was used to detect the expression profiles of circRNAs in TOF myocardial tissue and normal myocardial tissue, to analyse the differentially expressed circRNAs, to construct the ceRNA regulatory network of TOF using bioinformatics methods, to explore the possible pathogenesis of TOF without a genetic background, and to provide a new method for preventing the formation and development of TOF.

Conclusions

In summary, we established a ceRNA network mediated by differentially expressed circRNAs in TOF based on the “ceRNA hypothesis”. This study provides new insight for mechanistic investigations and may offer candidate diagnostic biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets for TOF. In addition, we propose that the hsa_circ_0007798/miR-199b-5p/HIF1A signalling axis regulates TOF progression. Further studies are still required to validate the sponge effects of specific circRNAs, such as hsa_circ_0007798.

Availability of data and materials

The microarray data produced in this study have been uploaded to the NCBI/GEO repository, and all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CHD:

-

Congenital heart disease

- TOF:

-

Tetralogy of Fallot;

- circRNA:

-

Circular RNA

- VSD:

-

Ventricular septal defect

- ncRNAs:

-

Noncoding RNAs

- LncRNAs:

-

Long ncRNAs

- HIF1A :

-

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- ceRNAs:

-

Competing endogenous RNAs

- MREs:

-

MiRNA response elements

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative PCR

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Program for Social Sciences

- pre mRNA:

-

Precursor mRNA

- Ss:

-

Splice site

- POL II:

-

RNA polymerase II

- RBP:

-

RNA binding protein

- MICRA:

-

Myocardial infarction-related circRNA

References

Simmons MA, Brueckner M. The genetics of congenital heart disease… understanding and improving long-term outcomes in congenital heart disease: a review for the general cardiologist and primary care physician. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29:520.

Hinton RB, Ware SM. Heart failure in pediatric patients with congenital heart disease. Circ Res. 2017;120:978–94.

Abouk R, Grosse SD, Ailes EC, Oster ME. Association of US state implementation of newborn screening policies for critical congenital heart disease with early infant cardiac deaths. JAMA. 2017;318:2111.

Seckeler M, Lawson E, Barber B, Klewer S. Percutaneous management of complex acquired aortic coarctation in an adult with tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;10:295.

Jones MI, Qureshi SA. Recent advances in transcatheter management of pulmonary regurgitation after surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot. F1000research. 2018;7:679.

Athanasiadis DI, Mylonas KS, Kasparian K, Ziogas IA, Avgerinos DV. Surgical outcomes in syndromic tetralogy of fallot: a systematic review and evidence quality assessment. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40(6):1105–12.

Wang B, Shi G, Zhu Z, Chen H, Fu Q. Sexual difference of small RNA expression in Tetralogy of Fallot. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12847.

Zaidi S, Brueckner M. Genetics and genomics of congenital heart disease. Circ Res. 2017;120:923–40.

Peng B, Han X, Peng C, Luo X, Deng L, Huang L. G9α-dependent histone H3K9me3 hypomethylation promotes overexpression of cardiomyogenesis-related genes in fetal mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:1036–45.

Yilbas A, Hamilton A, Wang Y, Mach H, Lacroix N, Davis DR, et al. Activation of GATA4 gene expression at the early stage of cardiac specification. Front Chem. 2014;2:12.

Gasiūnienė M, Petkus G, Matuzevičius D, Navakauskas D, Navakauskienė R. Angiotensin II and TGF-β1 induce alterations in human amniotic fluid-derived mesenchymal stem cells leading to cardiomyogenic differentiation initiation. Int J Stem Cells. 2019;12:251.

Gao J, Xu W, Wang J, Wang K, Li P. The role and molecular mechanism of non-coding RNAs in pathological cardiac remodeling. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:608.

Huang S, Li X, Zheng H, Si X, Li B, Wei G, et al. Loss of super-enhancer-regulated circRNA Nfix induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction in adult mice. Circulation. 2019;139:2857–76.

Li S, Teng S, Xu J, Su G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, et al. Microarray is an efficient tool for circRNA profiling. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20(4):1420–33.

Patop IL, Wüst S, Kadener S. Past, present, and future of circRNAs. The EMBO J. 2019; 38(16).

Han B, Chao J, Yao H. Circular RNA and its mechanisms in disease: from the bench to the clinic. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;187:31–44.

Kristensen LS, Andersen MS, Stagsted LV, Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB, Kjems J. The biogenesis, biology, and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:675–91.

O’Brien JE, Kibiryeva N, Zhou XG, Marshall JA, Bittel DC. Noncoding RNA expression in myocardium from infants with tetralogy of fallot. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:279–86.

Liao Z, Wang X, Zeng Y, Zou Q. Identification of DEP domain-containing proteins by a machine learning method and experimental analysis of their expression in human HCC tissues. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39655.

Wang X, Liao Z, Bai Z, He Y, Duan J, Wei L. MiR-93-5p promotes cell proliferation through down-regulating PPARGC1A in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification. Genes. 2018;9:51.

Long J, Xiong J, Mao J, Zhang H, Bai Y, Lin J, et al. Construction and investigation of a lncRNA-associated ceRNA regulatory network in cholangiocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:649.

Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–7.

Davis AP, Grondin CJ, Johnson RJ, Sciaky D, King BL, McMorran R, et al. The comparative toxicogenomics database: update 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D972–8.

Cunha SR, Hund TJ, Hashemi S, Voigt N, Li N, Wright P, et al. Defects in ankyrin-based membrane protein targeting pathways underlie atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2011;124:1212–22.

Moreau JL, Kesteven S, Martin EM, Lau KS, Yam MX, O'Reilly VC et al. Gene-environment interaction impacts on heart development and embryo survival. Development. 2019; 146: dev172957.

Herrer I, Roselló-Lletí E, Ortega A, Tarazón E, Molina-Navarro MM, Triviño JC, et al. Gene-expression network analysis reveals new transcriptional regulators as novel factors in human ischemic cardiomyopathy. BMC Med Genom. 2015;8:14.

Bittel DC, Zhou X-G, Kibiryeva N, Fiedler S, O’Brien Jr JE, Marshall J, et al. Ultra high-resolution gene-centric genomic structural analysis of a non-syndromic congenital heart defect, Tetralogy of Fallot. PloS one. 2014; 9(1).

Domnina YA, Kerstein J, Johnson J, Sharma MS, Kazmerski TM, Chrysostomou C, et al. Tetralogy of Fallot. Critical Care of Children with Heart Disease. Springer. 2020, pp 191–197.

Kumarswamy R, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113:676–89.

Alesha MA, Ni T, Khan A, Liu K, Zheng X. Circular RNA in cardiovascular disease. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5588–600.

Kreutzer FP, Fiedler J, Thum T. Non‐coding RNAs: key players in cardiac disease. The J Physiol (Lond.). 2019: 31291008.

Li X, Yang L, Chen L-L. The biogenesis, functions, and challenges of circular RNAs. Mol Cell. 2018;71:428–42.

Menendez-Montes I, Escobar B, Palacios B, Gómez MJ, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Flores L, et al. Myocardial VHL-HIF signaling controls an embryonic metabolic switch essential for cardiac maturation. Dev Cell. 2016;39:724–39.

Nonaka CKV, Cavalcante BRR, Alcântara ACD, Silva DN, Bezerra MDR, Caria ACI, et al. Circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers associated with cardiac remodeling and fibrosis in Chagas disease cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4064.

Li Z, Liu L, Hou N, Song Y, An X, Zhang Y, et al. miR-199-sponge transgenic mice develop physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:258–67.

Duygu B, Poels EM, Juni R, Bitsch N, Ottaviani L, Olieslagers S, et al. miR-199b-5p is a regulator of left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction. Non-coding RNA Res. 2017;2:18–26.

R Shane Tubbs A, Nicholas Gianaris, Mohammadali M Shoja, Marios Loukas.“The heart is simply a muscle” and the first description of the tetralogy of “Fallo”. Early contributions to cardiac anatomy and pathology by bishop and anatomist Niels Stensen (1638–1686). Int J Cardiol, 2012, (154): 312–315.

Soemedi R, Wilson IJ, Bentham J, Darlay R, Töpf A, Zelenika D, et al. Contribution of global rare copy-number variants to the risk of sporadic congenital heart disease[J]. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:489–501.

Rauch R, Hofbeck M, Zweier C, Koch A, Zink S, Trautmann U, et al. Comprehensive genotype-phenotype analysis in 230 patients with tetralogy of Fallot[J]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:321–31.

Egbe A, Uppu S, Lee S, Ho D, Srivastava S. Changing prevalence of severe congenital heart disease: a population-based study[J]. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:1232–8.

Sesllar S, Robinson M. Understanding sudden death risk in tetralogy of Fallot: from bedside to bench. Heart. 2017;103:333–4.

Russell MW, Chung WK, Kaltman JR, Miller TA. Advances in the understanding of the genetic determinants of congenital heart disease and their impact on clinical outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018, (7): e006906.

Morgenthau A, Frishman WH. Genetic origins of tetralogy of Fallot. Cardiol Rev. 2018;26:86–92.

MatosNieves A, Yasuhara J, Garg V. Another NOTCH in the genetic puzzle of tetralogy of fallot. Circ Res. 2019;124:462–4.

Memczak S, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–8.

Chen LL, Yang L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA Biol. 2015;12:381–8.

Wilusz JE. A 360° view of circular RNAs: From biogenesis to functions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9(4).

Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–57.

Capel B, Swain A, Nicolis S, Hacker A, Walter M, Koopman P, Good Fellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell. 1993, 73: 1019–1030.

Li Xiang, Yang Li, Chen Ling-Ling. The biogenesis, functions, and challenges of circular RNAs. Mol Cell. 2018;71(3):428–42.

Hansen TB, Veno MT, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Comparison of circular RNA prediction tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e58.

Abdelmohsen K, Panda AC, Munk R, Grammatikakis I, Dudekula DB, De S, Kim J, Noh JH, Kim KM, Martindale JL, et al. Identification of HuR target circular RNAs uncovers suppression of PABPN1 translation by CircPABPN1. RNA Biol. 2017;14:361–9.

Luo J, et al. Profiling circRNA and miRNA of radiation-induced esophageal injury in a rat model. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14605.

Wang K, et al. A circular RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy and heart failure by targeting miR-223. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2602–11.

Vausort M, et al. Myocardial infarction- associated circular RNA predicting left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1247–8.

Radka Cerychova, Romana Bohuslavova, Gabriela Pavlinkova. Adverse effects of HIF1A mutation and maternal diabetes on the offspring heart. Cerychova et al. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018, 17: 68.

Duncan B. Sparrow. Gavin Chapman. Sally L. Dunwoodie. Gene-environment interaction impacts on heart development and embryo survival. The Company of Biologists Ltd. 2019, 146: dev172957.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

While working on this manuscript, financial support was provided to the Project supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2020J01344) (Hua Cao) and the Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital of Fujian Province of China (grant No. YCXB 18-05 and No. YCXM 19-03) (Xinrui Wang). The funding body played no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing or the decision to publish this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceived and designed by HC, HY and XW. HY is responsible for the anatomical observations and the collection of heart specimens. HY and XW performed the data collection and analysis. HY drafted the manuscript. XW and HC checked the manuscript and revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital and conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each parent or legal guardian after reading the consent document and addressing their queries. All proper institutional review board approvals were obtained for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Table 1 Differentially expressed circRNAs between the TOF group and the healthy control group.

Additional file 2.

Table 2 ceRNA regulatory modules.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Wang, X. & Cao, H. Construction and investigation of a circRNA-associated ceRNA regulatory network in Tetralogy of Fallot. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 437 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02217-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02217-w