Abstract

Background

The incidence of concurrent cancer and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is increasing; however, the long-term patient prognoses remain unclear.

Methods

Five-year all-cause mortality data pertaining to patients in the Osaka Cancer Registry, who were diagnosed with colorectal, lung, prostate, and gastric cancers between 2010 and 2015, were retrieved and analysed together with linked patient administrative data. Patient characteristics (cancer type, stage, and treatment; coronary risk factors; medications; and time from cancer diagnosis to index admission for percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or IHD diagnosis) were adjusted for propensity score matching. Three groups were identified: patients who underwent PCI within 3 years of cancer diagnosis (n = 564, PCI + group), patients diagnosed with IHD within 3 years of cancer diagnosis who did not undergo PCI (n = 3058, PCI-/IHD + group), and patients without IHD (n = 27,392, PCI-/IHD- group). Kaplan–Meier analysis was used for comparisons.

Results

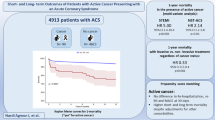

After propensity score matching, the PCI + group had better prognosis (n = 489 in both groups, hazard ratio 0.64, 95% confidence interval 0.51–0.81, P < 0.001) than the PCI-/IHD + group. PCI + patients (n = 282) had significantly higher mortality than those without IHD (n = 280 in each group, hazard ratio 2.88, 95% confidence interval 1.90–4.38, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

PCI might improve the long-term prognosis in cancer patients with IHD. However, these patients could have significantly worse long-term prognosis than cancer patients without IHD. Since the present study has some limitations, further research will be needed on this important topic in cardio-oncology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Continued advances in cancer treatment have led to dramatic increases in the number of survivors [1]. As a result, the incidence of those suffering from concomitant coronary artery diseases (CAD) and cancer is also increasing. Some studies have reported that cancer itself, as well as cancer therapy, increases the risk of cardiovascular events [2,3,4]. However, cancer patients have historically been excluded from most CAD intervention trials. With the recent introduction of the field of onco-cardiology, patients suffering from both diseases simultaneously are attracting significant attention from oncologists and cardiologists [5, 6]. Several studies have shown that cancer patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) exhibit higher all-cause mortality, bleeding, and other adverse cardiovascular events when compared with patients who have no history of cancer [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. This raises the question of whether PCI can improve long-term prognosis in patients with cancer and comorbid ischaemic heart disease (IHD).

Including cancer patients in studies is challenging, given the wide heterogeneity in cancer type, stage, and treatment. Recently, Potts et al. [10] compared the short-term outcomes of PCI in prostate, breast, colorectal, and lung cancer patients with those of patients with a history of cancer and those with no cancer. They found that patients with metastatic disease had worse prognoses. They also noted that the rate of each adverse event varied by cancer type. However, data on the long-term prognosis of cancer patients undergoing PCI has not been reported in the literature. Thus, this report presents a comparison of all-cause mortality between cancer patients with IHD who underwent PCI and cancer patients with IHD who did not undergo PCI. Furthermore, this study aimed to determine how the long-term prognosis of cancer patients with IHD who underwent PCI differed from those who did not undergo PCI, as well as those without concurrent cancer and IHD.

Methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Osaka International Cancer Institute (Approval number: 1707105108) and the study protocol was in accordance with the principles set out in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data sources

This was a multicentre retrospective cohort study using the Osaka Cancer Registry (OCR) and administrative data [14,15,16,17,18]. The OCR is a population-based cancer registry that compiles information on cancer diagnoses and outcomes in patients residing in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. OCR data include age, sex, history of smoking, type of cancer, date of cancer diagnosis, date of the last follow-up, date of any cause of death, and cancer stage (i.e., localised, regional to lymph nodes, regional by direct extension, and metastatic) according to SEER (surveillance, epidemiology, and end results) [19]). The OCR also includes treatment information (i.e., curative surgery/endoscopic treatment, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and radiation therapy). Cancer types are defined according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3). Furthermore, administrative data from Japan’s Diagnosis Procedure Combination Per-diem Payment System (DPC) were collected from 36 designated cancer care hospitals in Osaka Prefecture. The DPC data include medication and history of PCI. In addition, upon hospital admission, patient data on activities of daily living (ADL; Barthel Index score), smoking habits, and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnoses are recorded. OCR data are linked to administrative data at the patient level, using each hospital’s patient identification number.

Study population

Study investigators identified gastric (ICD-O-3 topographical codes: C16.x), colorectal (C18.x-C20.x), prostate (C61.x), and lung (C34.x) cancer patients who were diagnosed between 2010 and 2015. This decision was based on data that patients with these cancers underwent PCI most frequently (see Additional file 1: Figure S1). Exclusion criteria included a number of items: having undergone coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), history of myocardial infarction, history of PCI, and missing data (including vital status, DPC, and/or other baseline characteristics) at index admission for PCI or IHD for primary analysis (described below) and at cancer diagnosis for secondary analysis (described further on). The patient selection flowchart can be seen in Fig. 1. The presence of IHD, including angina pectoris, asymptomatic myocardial ischemia, and acute myocardial infarction, was determined as a patient receiving IHD as the main diagnosis, having IHD as comorbidity upon admission, or having IHD as an in-hospital complication of index admission based on ICD-10 in DPC data (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Exposure

Patients were categorised into 3 groups: (1) those diagnosed with IHD who underwent PCI (the PCI + group); (2) those diagnosed with IHD who did not undergo PCI (the PCI-/IHD + group); and (3) those without a diagnosis of IHD (PCI-/IHD- group). To assess its effects on long-term prognosis, only patients who underwent PCI within 3 years of their cancer diagnosis were included in the PCI + group. The 3-year threshold was chosen because it includes 90% of patients undergoing PCI after the diagnosis of cancer. Among patients with IHD not undergoing PCI, only those who had been diagnosed with IHD within 3 years of their cancer diagnosis were included in the PCI-/IHD + group. As a sensitivity analysis, all-cause mortality was also assessed for patients who had undergone PCI or had received a diagnosis of IHD within 1.5 years of their cancer diagnosis.

Potential confounders

Data on medications (statins, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and oral anticoagulants [warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants]), coronary risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, and overweight); and other confounders (atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, and chronic kidney disease) were retrieved from the DPC database according to ICD-10 codes (see Additional file 1: Table S1). The medication was considered in the analysis if it had been introduced before discharge from the index hospitalisation (see Additional file 1: Table S2). Overweight status was defined as a body mass index > 25 kg/m2. The Barthel Index was used to measure ADL, and patients were divided into 3 groups based on their scores: 0–39, 40–59, and 60–100.

Statistical analysis

In the primary analysis, we analysed the effect of PCI on long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with IHD by comparing the PCI + and PCI-/IHD + groups. Survival was calculated from the index admission for PCI or IHD. Subgroup analysis by cancer type was also performed. In the secondary analysis, the PCI+ and PCI−/IHD− groups were compared to examine the combined impact of PCI and IHD on cancer prognosis. Survival was calculated from the index cancer diagnosis. As a sensitivity analysis, the difference in all-cause mortality between the PCI + group, excluding those with the acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and the PCI−/IHD− group was assessed.

Propensity score-matched survival analyses were performed in both primary and secondary analyses. The propensity score for PCI treatment was calculated using all 22 covariates described in Table 1. For the subgroup analysis of lung cancer patients, small cell carcinoma (ICD-O-3 morphological codes: 8041-8045) was also included as a factor. After 1:1 matching, 5-year all-cause mortality was assessed using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Caliper width was set as 0.2 times the standard deviation of the propensity scores. The balance of each factor was assessed using the standardised difference. Since the time interval between cancer diagnosis and admission for PCI varied, it was considered to represent an immortal time bias in the secondary analysis. Consequently, we used extended Kaplan–Meier analysis by adjusting for immortal time bias [20,21,22] after propensity score matching. In the PCI + group, the number at risk during the interval between cancer diagnosis and admission for PCI was 0. Therefore, PCI + group patients were grouped with PCI−/IHD− group patients during no-risk periods, with survival analysis in both groups starting at the date of cancer diagnosis [22].

Cox proportional hazard analysis with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) for 5 years from PCI or IHD admission was also performed to confirm the robustness of the results. The entire cohort was weighted by stabilised average treatment effect weight [23]. Proportional hazards assumptions were confirmed by Schoenfeld residuals. For further confirmation, multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis of the propensity score-matched sample was performed with a history of PCI, age (continuous variable), sex, cancer type, cancer stage, Barthel Index, ACS, and interval from cancer diagnosis to index admission for PCI or IHD as covariates for the primary analysis. Each of these variables, except ACS and interval from cancer diagnosis to index admission for PCI or IHD, was used for the secondary analysis.

JMP (version 11.0; SAS Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used for data organisation and propensity score matching while graphing and all other analyses were performed using STATA (version 15; STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). Results meeting a 2-tailed P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and P < 0.1 was used to indicate a trend towards significance.

Results

Long-term prognosis of cancer patients according to PCI

In the primary analysis, the PCI + (n = 564; mean age 72 years) and PCI−/IHD+ (n = 3058; mean age 74 years) groups were compared. Baseline characteristics of the 2 groups are described in Table 1. The PCI + group had a lower prevalence of metastatic cancer, but a higher prevalence of ACS than the PCI-/IHD + group (33% vs. 15%). In terms of medication, PCI + group patients were more likely to receive β-blockers, statins, and ACE inhibitors. Furthermore, coronary risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and diabetes mellitus were more prevalent in the PCI + group.

To assess the effects of PCI, we compared the PCI + and PCI-/IHD + groups after propensity score matching. Adjusted variables were well-balanced after matching (standardised difference < 0.1). The PCI + group (n = 489) had significantly better prognoses than the PCI-/IHD + group (n = 489) (log-rank test, P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The Cox regression analysis with IPTW also found better prognoses in the PCI + group (n = 564) than in the PCI-/IHD + group (n = 3058) (hazard ratio [HR] 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59–0.96, P = 0.002]. Multivariable analysis showed that PCI was a significant independent predictor of all-cause mortality (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46–0.74, P < 0.001; see Additional file 1: Table S3). We also compared those who had undergone PCI or were diagnosed with IHD within 1.5 years (see Additional file 1: Table S4). The results also showed a better prognosis in the PCI + group (log-rank test, P = 0.011; see Additional file 1: Figure S2). Cox regression analysis with IPTW revealed better prognoses in the PCI + group (n = 394) than in the PCI−/IHD + group (n = 2621) (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.97, P = 0.030).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality in the PCI + and PCI−/IHD + groups. After propensity score matching, Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed. The starting point of the survival analysis was the admission date for PCI or IHD. The PCI + group had better long-term prognosis compared to the PCI−/IHD + group. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, IHD ischaemic heart disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

The effects of PCI on the long-term prognosis of each cancer type were also assessed (see Additional file 1: Tables S5 to S8). After propensity score matching, PCI + group patients with colorectal cancer had a significantly better prognosis (log-rank test, P = 0.043), while those with gastric cancer showed a trend toward improvement (log-rank test, P = 0.093) despite the relatively small number of patients (n = 157 and n = 106, respectively) (Fig. 3). Some variables had standardised difference > 0.1 in this propensity score-matched sample.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality according to cancer type. Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality in a colorectal, b lung, c prostate, and d gastric cancer patients was performed. Small cell carcinoma was considered a factor during propensity score matching of lung cancer patients. The starting point of the survival analysis was the admission date for PCI or IHD. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, IHD ischaemic heart disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Long-term prognosis of patients with IHD undergoing PCI and those without IHD

Differences in all-cause mortality between patients who had undergone PCI (PCI + group, n = 282) and those who had had no documented IHD (PCI−/IHD− group, n = 27,392) (Table 2) were assessed. All-cause mortality between the PCI + (n = 0 at cancer diagnosis) and PCI−/IHD− groups (n = 560 at cancer diagnosis) were compared after adjusting for immortal time bias. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the propensity score-matched groups showed significantly higher all-cause mortality in the PCI+ group (log-rank test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Multivariable analysis showed that PCI was an independent predictor of mortality (see Additional file 1: Table S9). Even after excluding ACS patients (see Additional file 1: Table S10), the PCI + group still showed higher mortality rates (log-rank test, P = 0.042) (see Additional file 1: Figure S4).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality in the PCI + and PCI−/IHD− groups. The PCI + and PCI−/IHD− groups were propensity score-matched as was done in the prior analyses. Immortal time bias was adjusted for by considering PCI + patients as part of the PCI−/IHD− group during the period from cancer diagnosis to PCI admission, as the PCI + group had no patients at risk. The starting point of the survival analysis was the date of cancer diagnosis for both groups, but the PCI + group was allowed to contribute to the risk of the PCI−/IHD− group in the period before PCI. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, IHD ischaemic heart disease, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

Impact of PCI on the survival of cancer patients with IHD

Our primary analysis suggests that PCI may lead to a better long-term prognosis in patients with certain cancers and IHD. Our results were verified using multiple tests such as IPTW and multivariable Cox proportional analysis. Additionally, similar results were observed after reducing the time interval from cancer diagnosis to index PCI or IHD from 3 to 1.5 years.

Cancer patients reportedly have a higher risk of cardiovascular events after PCI than non-cancer patients. Landes et al. [8] reported that cancer patients had higher rates of a composite of death, myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularisation (TLR), and CABG. Nakatsuma et al. [9] reported that the 5-year incidence of cardiac death was higher in cancer patients and that rates of definite or probable stent thrombosis also tended to be higher. A meta-analysis found that 1-year cardiovascular mortality after PCI was higher in cancer patients [11]. Taken together, these findings suggest that cancer can lead to the progression of atherosclerosis and increased cardiovascular mortality. In fact, Tabata et al. [13] reported that not only do cancer patients have higher 1-year TLR rates, but those with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels also have higher overall cardiovascular event rates (cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, unstable angina pectoris, TLR, non-TLR, and hospitalisation for heart failure decompensation). They speculated that increased inflammation in cancer patients might lead to the progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis. This may mean that cancer patients with IHD have a very high risk of cardiovascular events, which could explain why PCI and regular cardiology follow-up of our cancer patients reduced all-cause mortality.

We assessed the impact of PCI on each cancer type. However, despite the propensity score matching, the results were underpowered. Colorectal and gastric cancer patients in the PCI + group had significantly lower mortality and trends toward lower mortality, respectively, compared to PCI−/IHD + patients. This was consistent with the overall analysis. In contrast, no difference in mortality was observed between lung and prostate cancer patients in both groups. Since metastasis is more common in lung cancer patients, the advantage of PCI may be nullified by increased cancer lethality. In prostate cancer patients, a higher prevalence of a Barthel Index of 40–59, treatment with oral anticoagulants, and chemo/radiation/hormonal therapy, which were not sufficiently balanced after propensity score matching, might have affected the results. Furthermore, since prostate cancer has low lethality, there may be fewer reasons to forego PCI. Therefore, one possible explanation is that PCI-/IHD- group patients with prostate cancer might have had relatively low-risk IHD that did not require PCI. One of the major concerns with PCI is post-procedural bleeding. It has been shown that gastrointestinal cancer patients have higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding after PCI [24, 25]. Our results suggest that the advantages of PCI might outweigh bleeding risk.

The present study had several confounders and limitations due to the nature of its retrospective cancer-based cohort. Indeed, our study lacked an analysis of some significant cardiovascular-related factors as unmeasured confounders. For example, we could not determine the reason why PCI−/IHD + group patients did not undergo PCI. Nevertheless, the cancer-related background characteristics were very detailed in our study. Although it may be difficult to directly apply our study’s findings to daily practice, there are still some clinical implications. Cardiologists may hesitate to offer aggressive cardiovascular interventions to cancer patients considering their prognosis. However, according to our study, there should be less prevarication in performing the necessary intervention for IHD under the proper indication. In addition, cardiovascular intervention and outpatient follow-up by cardiologists might improve the prognosis of cancer patients with IHD. Furthermore, our study will encourage and provide a basis for further clinical trials or prospective investigations for better understanding of this issue in cardio-oncology.

Impact of IHD and PCI on the survival of cancer patients

Secondary analysis showed that cancer patients undergoing PCI had higher mortality compared to those who had no history of IHD. As shown in Fig. 4, the difference between the two groups increased over the first few months. Roule et al. reported that cancer patients undergoing PCI for ACS have higher rates of all-cause (relative risk [RR] 2.62, 95% CI 1.2–5.73) and cardiac deaths (RR 2.44, 95% CI 1.73–3.4,) compared to non-cancer patients [12]. Although their study population differed from ours, the results of the two investigations are consistent. In order to exclude the potential impact of ACS prevalence on the short-term prognosis, we analysed the mortality only in patients undergoing PCI for stable IHD as a sensitivity analysis. Similar to other results, long-term mortality was worse in the subgroup of patients who underwent PCI for stable IHD. This result may also be related to the elevated inflammatory state mentioned earlier [8, 9, 11, 13]. The PCI + group patients could have had a higher risk of cardiovascular events, including cardiac death, compared to the PCI−/IHD− group patients.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, since this was a retrospective registry-based cohort study, we could not adjust for all confounders. Second, we could not identify a history of coronary artery diseases or any related treatment that occurred before the beginning of administrative data collection in 2010. Third, cause of death data (e.g., cardiovascular or cancer-related) and PCI procedural variables (i.e., type of stent used) were not available. In addition, we did not have ischaemic parameters and disease extent data for IHD patients. Fourth, despite the use of a large cancer registry, the number of patients we identified who had undergone PCI was relatively small. Fifth, a substantial number of cancer patients were not hospitalised after being definitively diagnosed with cancer; therefore, our secondary analysis lacked ADL data (Barthel Index score). Sixth, the use of antiplatelet therapy was not assessed. Because antiplatelet treatment was contraindicated for most of the patients in the PCI−/IHD + group, antiplatelet therapy rates were not appropriate covariates for propensity score matching. Thus, it should be counted as a factor “not prevalent in PCI patients” in this study. To address these limitations, more studies are needed.

Conclusion

PCI might improve the long-term prognosis of cancer patients with IHD. However, cancer patients who undergo PCI could have significantly worse long-term prognoses than those without IHD. Since the present study has some unmeasured confounders and limitations, further prospective investigations of this important cardio-oncology topic are needed.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin II receptor blocker

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery diseases

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DPC:

-

Diagnosis Procedure Combination Per-diem Payment System

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision

- ICD-O-3:

-

International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition

- IHD:

-

Ischaemic heart disease

- IPTW:

-

Inverse probability of treatment weighting

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NA:

-

Not available

- OCR:

-

Osaka Cancer Registry

- OMI:

-

Old myocardial infarction

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- TLR:

-

Target lesion revascularisation

References

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:363–85.

Abdel-Qadir H, Austin PC, Lee DS, Amir E, Tu JV, Thavendiranathan P, et al. A population-based study of cardiovascular mortality following early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:88–93.

Hooning MJ, Aleman BM, van Rosmalen AJ, Kuenen MA, Klijn JG, van Leeuwen FE. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of breast cancer: a 25-year follow-up study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1081–91.

Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Munoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC committee for practice guidelines: the task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2768–801.

Campia U, Moslehi JJ, Amiri-Kordestani L, Barac A, Beckman JA, Chism DD, et al. Cardio-oncology: vascular and metabolic perspectives: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e579–602.

Hayek SS, Ganatra S, Lenneman C, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Leja M, Lenihan DJ, et al. Preparing the cardiovascular workforce to care for oncology patients: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2226–35.

Iannaccone M, D’Ascenzo F, Vadala P, Wilton SB, Noussan P, Colombo F, et al. Prevalence and outcome of patients with cancer and acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a BleeMACS sub study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7:631–8.

Landes U, Kornowski R, Bental T, Assali A, Vaknin-Assa H, Lev E, et al. Long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions in cancer survivors. Coron Artery Dis. 2017;28:5–10.

Nakatsuma K, Shiomi H, Morimoto T, Watanabe H, Nakagawa Y, Furukawa Y, et al. Influence of a history of cancer on long-term cardiovascular outcomes after coronary stent implantation (an observation from Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome Study-Kyoto Registry Cohort- 2). Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2018;4:200–7.

Potts JE, Iliescu CA, Lopez Mattei JC, Martinez SC, Holmvang L, Ludman P, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in cancer patients: a report of the prevalence and outcomes in the United States. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1790–800.

Quintana RA, Monlezun DJ, Davogustto G, Saenz HR, Lozano-Ruiz F, Sueta D, et al. Outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with cancer. Int J Cardiol. 2020;300:106–12.

Roule V, Verdier L, Blanchart K, Ardouin P, Lemaitre A, Bignon M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prognostic impact of cancer among patients with acute coronary syndrome and/or percutaneous coronary intervention. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:38.

Tabata N, Sueta D, Yamamoto E, Takashio S, Arima Y, Araki S, et al. Outcome of current and history of cancer on the risk of cardiovascular events following percutaneous coronary intervention: a Kumamoto University Malignancy and Atherosclerosis (KUMA) study. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2018;4:290–300.

Mohamad O, Tabuchi T, Nitta Y, Nomoto A, Sato A, Kasuya G, et al. Risk of subsequent primary cancers after carbon ion radiotherapy, photon radiotherapy, or surgery for localised prostate cancer: a propensity score-weighted, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:674–85.

Morishima T, Matsumoto Y, Koeda N, Shimada H, Maruhama T, Matsuki D, et al. Impact of comorbidities on survival in gastric, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. J Epidemiol. 2019;29:110–5.

Okawa S, Tabuchi T, Morishima T, Koyama S, Taniyama Y, Miyashiro I. Hospital volume and postoperative 5-year survival for five different cancer sites: a population-based study in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:985–93.

Taniyama Y, Tabuchi T, Ohno Y, Morishima T, Okawa S, Koyama S, et al. Hospital surgical volume and 3-year mortality in severe prognosis cancers: a population-based study using cancer registry data. J Epidemiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20190242.

Kawamura H, Morishima T, Sato A, Honda M, Miyashiro I. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival benefit in stage III colon cancer patients stratified by age: a Japanese real-world cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:19.

Young JL Jr, Roffers SD, Ries LAG, Fritz AG, Hurlbut AA. SEER summary staging manual—2000: codes and coding instructions. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2001.

Axtell AL, Bhambhani V, Moonsamy P, Healy EW, Picard MH, Sundt TM 3rd, et al. Surgery does not improve survival in patients with isolated severe tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:715–25.

Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:492–9.

Gleiss A, Oberbauer R, Heinze G. An unjustified benefit: immortal time bias in the analysis of time-dependent events. Transpl Int. 2018;31:125–30.

Austin PC. Variance estimation when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) with survival analysis. Stat Med. 2016;35:5642–55.

Patel NJ, Pau D, Nalluri N, Bhatt P, Thakkar B, Kanotra R, et al. Temporal trends, predictors, and outcomes of in-hospital gastrointestinal bleeding associated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1150–7.

Shivaraju A, Patel V, Fonarow GC, Xie H, Shroff AR, Vidovich MI. Temporal trends in gastrointestinal bleeding associated with percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis of the 1998–2006 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. Am Heart J. 2011;162(1062–8):e5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [Grant Number JP20K18869]; and a Health, Labour and Welfare Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan [Grant Number H30-Gantaisaku-ippan-009]. The funders had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N., T.M., T.Otsuka, T.K., M.F. wrote the main manuscript text and S.O., Y.F., T.F., R.K., T.Y., W.S., T.Oka., T.T., I.M. prepared database, figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Osaka International Cancer Institute (Approval number: 1707105108) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary tables and figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishikawa, T., Morishima, T., Okawa, S. et al. Multicentre cohort study of the impact of percutaneous coronary intervention on patients with concurrent cancer and ischaemic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 177 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01968-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01968-w