Abstract

Background

Up to over half of the patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are reported to undergo spontaneous reperfusion without therapeutic interventions. Our objective was to evaluate the applicability of T wave inversion in electrocardiography (ECG) of patients with STEMI as an indicator of early spontaneous reperfusion.

Methods

In this prospective study, patients with STEMI admitted to a tertiary referral hospital were studied over a 3-year period. ECG was obtained at the time of admission and patients underwent a PPCI. The association between early T wave inversion and patency of the infarct-related artery was investigated in both anterior and non-anterior STEMI.

Results

Overall, 1025 patients were included in the study. Anterior STEMI was seen in 592 patients (57.7%) and non-anterior STEMI in 433 patients (42.2%). Among those with anterior STEMI, 62 patients (10.4%) had inverted T and 530 (89.6%) had positive T waves. In patients with anterior STEMI and inverted T waves, a significantly higher TIMI flow was detected (p value = 0.001); however, this relationship was not seen in non-anterior STEMI.

Conclusion

In on-admission ECG of patients with anterior STEMI, concomitant inverted T wave in leads with ST elevation could be a proper marker of spontaneous reperfusion of infarct related artery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) and thrombolytic therapy have been suggested as the essential therapeutic techniques in the management of patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [1]. It has been reported by some angiographic studies that 7–57% of patients with STEMI developed spontaneous reperfusion (SR) prior to PPCI [2,3,4,5,6,7]. In such cases, fibrinolytic therapy may not be advantageous in salvaging the myocardial ischemia because the culprit vessel is already partially patent and fibrinolytic therapy may enhance bleeding risk. Therefore, initial conservative treatment for patients with SR has been proposed and supported as a safe strategy by some previous investigations [4, 5, 8]. However, current guidelines of AHA/ACC and ESC do not consider spontaneous reperfusion as a contraindication of PPCI or thrombolytics in patients with STEMI [1, 9]. Due to the time limitations of cardiac interventions for STEMI patients, imaging studies or other laboratory tests could not be considered prior to PPCI for evaluation of presence of SR in infarct-related artery (IRA). However, electrocardiogram (ECG) can be used as an available, rapid, and easily interpretable tool in these situations. Atar et al. have described the ECG markers of reperfusion including resolution of ST-segment elevation, altered QRS appearance, T wave changes, and reperfusion arrhythmias [10]. A few studies have demonstrated that early T wave inversion can be regarded as a useful marker indicating spontaneous subendocardial reperfusion [8, 11, 12]. It was also associated with a higher patency rate of IRA and improvement in left ventricular function [11, 12]. However, the associations between T wave inversion and angiographic findings have not yet been evaluated in large-scale studies. Although ST elevation resolution more than 50% is a good marker for reperfusion in patients with at least two serial ECGs, it could not be used in patients with single ECG, presenting to emergency room with relived chest pain and 1–2 mm ST elevation and no base ECG. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of on admission T wave inversion in the presenting ECG of acute STEMI patients undergoing PPCI with spontaneous reperfusion of the infarct related artery.

Methods

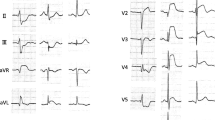

In this prospective study, patients with acute STEMI undergoing PPCI from May 2016 to May 2019 were evaluated. Patients with a history of previous MI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), those admitted after more than 6 h of the onset of their symptoms, those having received thrombolytics prior to admission, those with left bundle branch block (LBBB), right bundle branch block (RBBB), intraventricular conduction delay (IVCD) or ventricular rhythms, and those with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defibrillators were excluded from study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Demographic characteristics, underlying clinical condition, and the duration of time from the onset of symptoms, were recorded for each participant. An ECG using standard method was obtained from each participant at the time of admission. All ECGs were reviewed by two expert cardiologist prior to PPCI. The determination of STEMI was done according to the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial ischemic ECG criteria. Inverted T wave was defined as a T wave > 1 mm below the isoelectric line in two or more adjacent leads that had maximum ST-segment elevation. In the case of biphasic T wave, it was considered as inverted T wave if T wave was > 1 mm below the isoelectric line in the terminal part of T wave (Fig. 1).

PPCI was conducted by an expert interventional cardiologist and angiographic characteristics including coronary anatomy, the site of the culprit vessel, and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow in the IRA were determined. A TIMI flow ≥ 2 (2, 3) was considered as high flow and a TIMI flow < 2 (0–1) as low flow.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of all variables was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Mean and standard deviation of quantitative variables and frequency and percentage of categorical variables were reported. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U were used to compare quantitative variables between the two groups. Chi-square was used for categorical variables. SPSS version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used for all analyses. A p value < 0.05 was defined as being statistically significant.

Results

Overlay, 1150 patients with STEMI were studied, of whom 125 patients were excluded due to the following reasons. In 67 patients, there was a positive history of MI or CABG; in 20 patients, LBBB, RBBB or IVCD was present; in 24 patients, duration of chest pain was longer than 6 h; and in 14 patients, streptokinase was administrated prior to hospital admission. Baseline characteristics of the 1025 patients included in the study are described in Table 1. Inverted T wave was seen in 86 (8.4%) patients, among whom 62 patients (72.1%) had anterior and 24 patients (27.9%) had non-anterior STEMI. T wave inversion occurred mostly when IRA vessel for STEMI was the left anterior descending artery. No significant difference was seen in baseline characteristics (including age, sex, and familial history of ischemic heart disease, smoking, time from onset of symptoms, left ventricular ejection fraction, and type of STEMI) of those with inverted T wave and those with positive T waves (Table 1). TIMI flow ≥ 2 was seen in 56.9% of those with inverted T wave while only 9% of patients with positive T wave had a TIMI flow ≥ 2 (p value, 0.0001).

Anterior STEMI was seen in 592 patients (57.8%), of which 62 patients (10.4%) had concomitant on admission inverted T wave. In patients with anterior STEMI and a negative T wave TIMI flow was significantly higher (χ2 [1, N = 592], 203.41; p value, < 0.001); however, in non-anterior STEMI group, an on admission negative T in leads with ST elevation was not associated with high TIMI flow (χ2 [1, N = 433], 0.46; p value, 0.496; Table 2). The same associations remained in sub-group analysis in both anterior (Fig. 2) and non-anterior STMI patients (Fig. 3). The sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values of inverted T wave for diagnosis of high TMI flow were 55.56, 96.67, 72.58, and 93.21%, respectively.

Discussion

We evaluated the applicability of T wave inversion for predicting IRA patency in a prospective large-scale study. The results pointed to a significant relationship between on admission T wave inversion and patency of the culprit vessel in acute anterior STEMI.

Current guidelines of AHA or ESC advises PPCI or thrombolytics for all STEMI patients admitted within the initial hours of the onset of symptoms. However, as our results showed, a significant percent of patients with STEMI had spontaneous reperfusion of IRA. The incidence of SR in STEMI has been variedly reported by previous studies in a range of 7–57% [2,3,4,5,6,7]. This discrepancy could be due to different definitions of SR or the timing of assessments [13]. In our study, we used angiography for the determination of SR, which was suggested as the most reliable method in previous research [2,3,4,5,6,7].

By means of a better identification of patients with SR, a significant proportion of patients previously indicated for PPCI can be considered for conservative treatments [4, 5, 8]. In order to design an appropriate reperfusion protocol that considers the possibility of SR, sensitive and specific diagnostic tools are necessary to detect the presence or absence of SR prior to PPCI. Due to the pressure of time for rapid revascularization of patients with STEMI, imaging or other laboratory tests may not be beneficial. However, ECG as an available, readily applicable, low-cost, and non-invasive tool can be considered on these occasions. Our results support the applicability of T wave inversion in ECG as a marker of SR. Consistent with our findings, Hira et al. suggested that negative T wave upon the presentation of ECG could be a sign of spontaneous thrombolysis in patients with anterior STEMI [11]. Nakajima et al. demonstrated that the amplitude of negative T wave within 48 h of MI was inversely correlated with the extent of hypokinetic area of the heart; this predictive power was appreciated in both anterior and inferior STEMIs [14]. However, there was no relationship between T wave inversion and patency rate of non-anterior STEMI patients in our study. Similarly, this association in non-STEMI was not confirmed in the study by Hira et al. [11]. The reported positive and negative predictive values by the study of Hira et al. were similar to those emerging in our study. However, they reported a higher sensitivity and relatively lower specificity, which could be due to retrospective design and relatively small sample size in that study. The sensitivity and specificity reported by Alsaab et al. were 43.8 and 89.2%, respectively [12]. Studies on the effectiveness of PPCI have also reported T wave inversion as an important element for successful reperfusion. Hirota et al. indicated that negative T wave develops within only 0.5–5 h of successful reperfusion [15]. Moreover, non-inverted T wave 24 h after anterior STEMI predicted a LVEF less than 40%, by 90% sensitivity and 75% specificity [16]. The cornerstone of higher IRA patency in patients with negative T wave and anterior STEMI is unknown. More collateral circulation in LAD and RCA territories was shown in Wang et al. [17] study. Better perfusion through collateral arteries and subsequently better endothelial function could maintain blood flow after spontaneous reperfusion.

Considering ischemic and bleeding complications of PPCI [18] and given the fact that PPCI is not available in some medical centers and that fibrinolytic therapy can be life-threatening in patients who are at risk of bleeding, it seems that fibrinolytic therapy in patients with acute anterior STEMI and early T wave inversion upon ECG presentation (who have ST elevation in on admission ECG but negative T wave present in leads with ST elevation, too), especially in those with concomitant chest pain reduction, may not be an appropriate therapeutic strategy.

Our study suffered from some inevitable limitations. Due to the large number of patients included in the study, PPCI and assessment of TIMI flow could not be performed by a single cardiologist to reduce possible discrepancies. Having said that, we did make attempts to follow the standard method for all patients. Moreover, due to the prospective design of the study, the cardiologist that performed PPCI was not blinded to patients’ ECG.

TIMI flow is considered a strong predictor of long term outcome of patients with STEMI [19]. However, future studies are warranted to evaluate the long term outcome of STEMI patients presenting with positive/inverted T wave.

Conclusion

In on-admission ECG of patients with anterior STEMI, concomitant inverted T wave in leads with ST elevation could be a good marker of spontaneous reperfusion of infarct related artery.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material collected during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiography

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending artery

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- STEMI:

-

ST elevation myocardial infraction

- PPCI:

-

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention

- TIMI:

-

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

- MI:

-

Myocardial infraction

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- LBBB:

-

Left bundle branch block

- RBBB:

-

Right bundle branch block

- IVCD:

-

Intraventricular conduction delay

References

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2017;39(2):119–77.

Christian TF, Milavetz JJ, Miller TD, Clements IP, Holmes DR, Gibbons RJ. Prevalence of spontaneous reperfusion and associated myocardial salvage in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1998;135(3):421–7.

DeWood MA, Spores J, Notske R, Mouser LT, Burroughs R, Golden MS, et al. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(16):897–902.

Lee CW, Hong M-K, Lee J-H, Yang H-S, Kim J-J, Park S-W, et al. Determinants and prognostic significance of spontaneous coronary recanalization in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(8):951–4.

Steg PG, Himbert D, Benamer H, Karrillon G, Boccara A, Aubry P, et al. Conservative management of patients with acute myocardial infarction and spontaneous acute patency of the infarct-related artery. Am Heart J. 1997;134(2):248–52.

Stone GW, Cox D, Garcia E, Brodie BR, Morice M-C, Griffin J, et al. Normal flow (TIMI-3) before mechanical reperfusion therapy is an independent determinant of survival in acute myocardial infarction: analysis from the primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction trials. Circulation. 2001;104(6):636–41.

Tamis-Holland JE, Palazzo A, Stebbins AL, Slater JN, Boland J, Ellis SG, et al. Benefits of direct angioplasty for women and men with acute myocardial infarction: results of the global use of strategies to open occluded arteries in acute coronary syndromes (GUSTO II-B) Angioplasty Substudy. Am Heart J. 2004;147(1):133–9.

Rimar D, Crystal E, Battler A, Gottlieb S, Freimark D, Hod H, et al. Improved prognosis of patients presenting with clinical markers of spontaneous reperfusion during acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2002;88(4):352–6.

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, De Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–140.

Atar S, Fu Y, Wagner GS, Rosanio S, Barbagelata A, Birnbaum Y. Usefulness of ST depression with T-wave inversion in leads V4 to V6 for predicting one-year mortality in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (from the electrocardiographic analysis of the global use of strategies to open occluded coronary arteries IIB trial). Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(7):934–8.

Hira RS, Moore C, Huang HD, Wilson JM, Birnbaum Y. T wave inversions in leads with ST elevations in patients with acute anterior ST elevation myocardial infarction is associated with patency of the infarct related artery. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(4):472–7.

Alsaab A, Hira RS, Alam M, Elayda M, Wilson JM, Birnbaum Y. Usefulness of T wave inversion in leads with ST elevation on the presenting electrocardiogram to predict spontaneous reperfusion in patients with anterior ST elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(2):270–4.

Bainey KR, Fu Y, Wagner GS, Goodman SG, Ross A, Granger CB, et al. Spontaneous reperfusion in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: comparison of angiographic and electrocardiographic assessments. Am Heart J. 2008;156(2):248–55.

Nakajima T, Kagoshima T, Fujimoto S, Hashimoto T, Dohi K. The deeper the negativity of the T waves recorded, the greater is the effectiveness of reperfusion of the myocardium. Cardiology. 1996;87(2):91–7.

Hirota Y, Kita Y, Tsuji R, Hanada H, Ishii K, Yoneda Y, et al. Prominent negative T waves with QT prolongation indicate reperfusion injury and myocardial stunning. J Cardiol. 1992;22(2–3):325–40.

Kosuge M, Kimura K, Nemoto T, Shimizu T, Mochida Y, Nakao M, et al. Clinical significance of inverted T-waves during the acute phase of myocardial infarction in patients with myocardial reperfusion. J Cardiol. 1995;25(2):69–74.

Wang B, Han Y-L, Li Y, Jing Q-M, Wang S-L, Ma Y-Y, et al. Coronary collateral circulation: effects on outcomes of acute anterior myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Geriat Cardiol JGC. 2011;8(2):93–8.

Vink MA, Amoroso G, Dirksen MT, van der Schaaf RJ, Patterson MS, Tijssen JGP, et al. Routine use of the transradial approach in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: procedural aspects and outcomes in 2209 patients treated in a single high-volume centre. Heart. 2011;97(23):1938–42.

Bailleul C, Aissaoui N, Cayla G, Dillinger JG, Jouve B, Schiele F, et al. Prognostic impact of prepercutaneous coronary intervention TIMI flow in patients with ST-segment and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Results from the FAST-MI 2010 registry. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(2):101–8.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by a fund from the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AR, BS, SG, SRSE; Methodology: AR, BS, BK, NA, RH; Formal analysis and investigation: SRSE, BS, RH; Writing—original draft preparation: SRSE; Writing—review and editing: AR, NA, BK, BS; Funding acquisition: AR; Resources: SG, RH, Supervision: AR, BS, RH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by medical ethics committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was granted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranjbar, A., Sohrabi, B., Sadat-Ebrahimi, SR. et al. The association between T wave inversion in leads with ST-elevation and patency of the infarct-related artery. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01851-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01851-8