Abstract

Background

Health literacy on cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) plays an effective role in preventing or delaying the disease onset as well as in impacting the efficacy of their management. In view of the projected low health literacy in Tanzania, we conducted this cross-sectional survey to assess for CVD risk knowledge and its associated factors among patient escorts.

Methods

A total of 1063 caretakers were consecutively enrolled in this cross-sectional study. An adopted questionnaire consisting of 22 statements assessing various CVD risk behaviors was utilized for assessment of knowledge. Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess for factors associated with poor knowledge of CVD risks.

Results

The mean age was 40.5 years and women predominated (55.7%). Over two-thirds had a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, 18.5% were alcohol drinkers, 3.2% were current smokers, and 47% were physically inactive. The mean score was 78.2 and 80.0% had good knowledge of CVD risks. About 16.3% believed CVDs are diseases of affluence, 17.4% thought CVDs are not preventable, and 56.7% had a perception that CVDs are curable. Low education (OR 2.6, 95%CI 1.9–3.7, p < 0.001), lack of health insurance (OR 1.5, 95%CI 1.1–2.3, p = 0.03), and negative family history of CVD death (OR 2.2, 95%CI 1.4–3.5, p < 0.001), were independently associated with poor CVD knowledge.

Conclusions

In conclusion, despite of a good level of CVD knowledge established in this study, a disparity between individual’s knowledge and self-care practices is apparent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the pervasive struggle against infectious diseases continue, sub Saharan Africa (SSA) is facing a rapid epidemiological transition characterized by an increasing predominance of chronic diseases particularly those affecting the cardiovascular system [1]. Although the ever-present communicable diseases remain the leading contributors to disease burden in the SSA region, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are escalating at an alarming pace and it is projected that coming 2030 they will become the leading cause of morbidity and mortality [2, 3]. Nevertheless, low-middle income countries (SSA region inclusive) are currently witnessing a disturbingly disproportionate share of global NCDs deaths (i.e. > 75%) [4]. Owing to urbanization and sedentary life-style adoption, several NCD risk factors (i.e. smoking, heavy drinking, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity and overweight) are increasingly widespread in SSA communities and are postulated to be the drivers of the rapidly growing CVD burden in the region [4,5,6].

By virtue of their chronic nature, CVDs are of long duration and generally slow in progression necessitating life-long care inevitably with continuous expenditure [3, 5]. Nonetheless, these conditions are largely preventable through life-style modification to curb the exposure to the established risk factors [1,2,3]. It is evident that health literacy of CVD risk factors plays a considerably effective role in preventing or delaying the onset of disease as well as in impacting the efficacy of their management [7,8,9,10]. Likewise, persons with low functional health literacy have been associated with diminished use of the health system, less likelihood of engaging in health-promoting behaviors and poorer overall health outcomes [7,8,9,10].

Whilst SSA region is having one of the lowest adult literacy rates (65%) [11] in the world, just about a third of the Tanzanian population is estimated to have adequate health literacy [12]. Several studies have addressed the growing burden and pattern of CVD risk factors; however, there is dearth of information regarding public knowledge of CVD risk factors in SSA region particularly Tanzania. In this cross-sectional survey, we sought to assess the CVD risk knowledge and its associated factors among companions of outpatients attending a tertiary-level cardiovascular hospital in Tanzania. Such estimation of the baseline knowledge regarding CVD risks has potential public health relevance particularly in the development of targeted educational programs which are pivotal amidst the rapidly rising crisis.

Methods

Recruitment process and definition of terms

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between December 2019 and February 2020 at Jakaya Kikwete Cardiac Institute (a tertiary care public teaching hospital) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. A consecutive sampling method was utilized to recruit consented individuals who escorted known patients with CVD for a scheduled clinic visit. A structured questionnaire bearing questions pertaining to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, measurement of key vitals (blood pressure, blood sugar, height, weight and waist circumference), and standard questions for assessing CVD risk knowledge was utilized. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Vital Sign (PAVS) scale [13]; with scores of 0 min/week denoting inactivity, 1 - < 150 min/week signifying underactivity and ≥ 150 min/week indicating physical activeness. We defined underweight as BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, normal: BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and obese: BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2 [14]. Individuals who smoked at least 1 cigarette in the past 6 months were regarded as current smokers, those who last smoked over 6 months or self-reported quitting smoking were considered past smokers and those who never smoked were regarded as non-smokers. Alcohol drinking was defined as at least a once consumption every week. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg, or use of blood pressure lowering agents [15]. Diabetes was diagnosed using a random blood glucose (RBG) ≥11.1 mmol/L and/or fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥7 mmol/L or use of glucose-lowering agents [16]. An adopted questionnaire consisting of 22 statements assessing various CVD risk behaviors was utilized for assessment of knowledge [17]. A percentage score for each participant was computed by dividing the sum of correct responses divided by the total number of questions (i.e. 22) multiplied by 100. A score of < 50% was classified as low; 50–69% moderate and ≥ 70% good knowledge [18, 19].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by STATA v11.0 software. Summaries of continuous variables are presented as means (± SD) and categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the Pearson Chi square test and student’s T-test respectively. Bivariate analyses were performed to assess for factors associated with poor knowledge of CVD risks. Factors included in this analysis were age, sex, education level, marital status, employment status, residence, possession of health insurance, BMI, self-perceived health status, medical check-up history, self-reported knowledge of CVDs, family history of CVD, family history of CVD-related death, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol use, dietary habits, hypertension and diabetes history. Wald Chi-Square tests was used to assess for the interaction terms, with a p < 0.05 cut-off used as criteria for inclusion in multivariate analysis. Variables maintained in the multivariate model underwent stepwise and backward selection procedures. Odd ratios with 95% confidence intervals and p-values are reported. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and all tests were two tailed.

Results

Study population

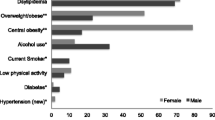

A total of 1063 individuals who escorted outpatients with established diagnosis of CVD were consecutively enrolled in this study. Table 1 displays the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants. Their mean age was 40.5 years and there was a female predominance (55.7%). Majority (59%) of participants had at least secondary school education and 79.4% had a regular income generating activity. Over 85% of participants resided in urban areas and just over a third were health insured. Regarding participants’ relationship to the patient: 13.4% were spouses, 62.2% were children, 15.2% were siblings, 3.6% were parents and 5.6% were friends. Over two-thirds (66.8%) of participants had a BMI ≥ 25, 18.5% were alcohol drinkers, 3.2% were current smokers, 17.8% reported a regular healthy eating, and 47% were physically inactive. Nearly one-fifth (19.2%) of participants had a personal history of hypertension and 4.1% were known to have diabetes mellitus.

Knowledge and attitude regarding CVD risk factors

While 583 (54.9%) of participants had never had a general health check-up before, 41.3% had a perception of being in good health while 34.4% reported to have knowledge of CVD risk factors. Table 2 summarizes responses to the 22 questions used to assess knowledge about CVD risk factors. The mean CVD knowledge score was 78.2% with a range of 31.8–100%. A total of 847 (79.7%) participants had good knowledge, 204 (19.2%) had moderate knowledge, and 12 (1.1%) had low knowledge of CVD risk factors. About 16.3% believed CVD are diseases of rich people and 42.4% were unaware that they are the leading cause of mortality globally. Additionally, 17.4% thought CVD are not preventable, 67.4% believed one may know that they have CVD based on symptoms alone and 56.7% had a perception that CVD are curable. Smoking was recognized by 77% as a CVD risk, physical inactivity by 95.6%, excessive alcohol drinking by 90.1%, overweight by 90.1%, high-salt diet by 85.9%, and elevated cholesterol by 92.9% of participants. Furthermore, while just 38.6% were aware that men have a higher risk of CVD compared to women, 65.6% acknowledged positive CVD family history as a risk, whereas 89.5 and 72.4% knew that hypertension and diabetes respectively are risk factors for CVD.

Factors associated with knowledge of CVD risk factors

Table 3 displays findings of chi-square analyses of various characteristics by CVD knowledge status (i.e. score < 70% vs score ≥ 70%). Participants with low education had a higher likelihood of having poor knowledge of CVD risks compared to individuals with at least secondary education (30.8% vs 12.9%, p < 0.001). Moreover, individuals who possessed a health insurance displayed higher rates of good CVD knowledge compared to their uninsured counterparts (89.4% vs 75.2%, p < 0.001). Likewise, non-smokers showed a higher chance of having a good CVD knowledge compared to current smokers (80.4% vs 58.8%, p < 0.01). Furthermore, physically inactive participants had inferior likelihood of having good CVD knowledge compared to their physically active counterparts (77.0% vs 82.1%, p = 0.04). Additionally, participants with unhealthy eating pattern displayed a higher chance of having poor knowledge compared regular healthy dieters (22.3% vs 16.7%, p = 0.03). Participants with a positive family history of CVD death displayed a superior CVD risks knowledge compared to ones without a CVD-related death in the family, (88.5% vs 77.4%, p < 0.001).

A total of seventeen potential characteristics associated with knowledge of CVD risks were featured in logistic regression analysis, Table 4. During bivariate analyses seven out of the seventeen factors showed significant associations (i.e. p < 0.05) and were subsequently included in the multivariate regression model to control for confounders. At the end of multivariate regression analysis, three factors remained independently associated with poor CVD risks knowledge. These included: low education level (OR 2.6, 95%CI 1.9–3.7, p < 0.001), lack of health insurance (OR 1.5, 95%CI 1.1–2.3, p = 0.03), and negative family history of CVD death (OR 2.2, 95%CI 1.4–3.5, p < 0.001).

Discussion

As the NCD epidemic continues to accelerate amidst the ongoing infectious diseases battle, health-care systems in SSA are increasingly regarding CVDs in particular and NCDs in general as a top public health priority [20]. To curb this distressing trend, health literacy has a prominent significance in prevention of CVD both at the primary and secondary levels [7,8,9,10]. Sorensen K et al. [21] defined health literacy as the “individual’s knowledge, motivation, and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgements and take decisions in everyday life concerning health care, disease prevention, and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course”. Inspite of its evidence-based [7,8,9,10] benefits in NCDs prevention, variably low rates of health literacy have been documented around the globe making public health measures particularly the development and implementation of targeted educational programs challenging or ineffective.

With about four-fifths of participants having an overall adequate knowledge regarding CVD risk factors, this present study demonstrated a modest level of health literacy in an urban setting of SSA. Our rates of CVD literacy echoes findings of previous studies from South Africa [17], Iran [22] and Malaysia [23] which produced knowledge rates of 75.3, 78.7 and 81% respectively. Contrary to our findings, regional studies from Nigeria [24] (44%) and Cameroon [25] (47.5%) revealed considerably low rates of CVD literacy. This observed variability in literacy rates between cited studies could be explained by the education-level differences among study participants and diversity of tools used for knowledge assessment. With regards to knowledge of specific risk behaviors, over nine-tenth of participants in this study recognized excess body weight, physical inactivity, and excess alcohol intake as risks, while more than three-quarters acknowledged smoking, unhealthy diet, hypertension and diabetes as attributable risks.

A wide variation of knowledge rates regarding individual risk factors is observed in the literature. For instance, smoking [17, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] has been recognized as a CVD risk by 36.2–93.2% of participants, excess alcohol intake by 40.7% [29]–65% [31], unhealthy diet [23,24,25,26, 28,29,30,31, 33] by 2.8–88%, physical inactivity [17, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33] by 1.2–96%, excess body weight [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33] by 1.6–100%, hypertension [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33] by 6.2–94% and diabetes [17, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] by 5.3–92.4%. Astonishingly, despite of a predominant blood-relationship between study participants and the escorted patients, just over one-third of participants realized they are living in a family with a positive CVD history and less than two-thirds were aware that it increases ones risk of CVD. In unison to our findings, studies by Awad et al.26 (62.6%), George et al.27 (68%), and Shafiq et al.28 (60%) revealed similar rates of recognition of family history as an attributable risk of CVD. Nonetheless, in a couple of other studies [25, 29, 30] majority (> 50%) of participants were unaware of the increased risk of acquiring CVD in the presence of a positive family history.

Irrespective of a predominant positive family history of CVD and acknowledgement of the importance of regular check-ups by large majority of participants, over a half of study subjects have never had a basic check-up their entire lives. Notwithstanding the relatively good CVD risk knowledge, risk behaviors were disproportionately high among participants of this present study. For instance, although excess body weight was recognized as a risk by over 90% of participants just one-third had a healthy weight. Similar pattern was observed with nearly 96% recognizing physical inactivity as a risk and yet just about a half of participants were physically active. Furthermore, certain risk factors (i.e. overweight, hypertension, and diabetes) revealed comparatively similar rates of knowledge to participants free from such risks. Nevertheless, current smokers, physically inactive and unhealthy eaters displayed inferior knowledge rates compared to their counterparts with healthy behaviors respectively.

Conclusions

Despite a fairly good level of knowledge regarding CVD risk factors established in this study, a vivid disconnection between individual’s knowledge and self-care practices (i.e. CVD risk behaviors) is apparent. These findings reflects alarming public health concerns and underscore the urgent need to establish and implement wide-spread and effective educational initiatives aiming at mitigating the community’s practices towards cardiovascular risk factors.

Availability of data and materials

The final version of data set supporting the findings of this paper is submitted together with this manuscript to the editorial committee. All the raw data is included in this manuscript. There are no ethics restrictions preventing the sharing of the raw data.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- RBG:

-

Random blood glucose

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

Hamid S, Groot W, Pavlova M. Trends in cardiovascular diseases and associated risks in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the evidence for Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania. Aging Male. 2019;22(3):169–76.

Holmes MD, Dalal S, Volmink J, et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: the case for cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000244.

Gouda HN, Charlson F, Sorsdahl K, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019;7(10):1375–87.

Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UK, et al. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2013. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2015;26:S6–10.

Keates AK, Mocumbi AO, Ntsekhe M, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Africa: epidemiological profile and challenges. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:273–93.

Siddharthan T, Ramaiya K, Yonga G, et al. Noncommunicable diseases in East Africa: assessing the gaps in care and identifying opportunities for improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:1506–13.

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107.

Joshi C, Jayasinghe UW, Parker S, et al. Does health literacy affect patients’ receipt of preventative primary care? A multilevel analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15.

Lim S, Beauchamp A, Dodson S, et al. Health literacy and fruit and vegetable intake in rural Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:2680–4.

von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf MS, et al. Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:860–77.

The UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Literacy Rates Continue to Rise from One Generation to the Next. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs45-literacy-rates-continue-rise-generation-to-next-en-2017.pdf.

Muhanga M, Malungo JRS. Health literacy and its correlates in the context of one health approach in Tanzania. Journal of Co-operative and Business Studies (JCBS) 2018; 1(1).

Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: clinical and research applications. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:2259–79.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. About Adult BMI. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52.

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Sec. 2. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care 2015; 38(Suppl. 1):S8–S16.

Burger A, Pretorius R, Fourie Carla MT, et al. The relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and knowledge of cardiovascular disease in African men in the north-West Province. Health SA Gesondheid (Online). 2016;21(1):364–71.

Amadi CE, Lawal FO, Mbakwem AC, et al. Knowledge of cardiovascular disease risk factors and practice of primary prevention of cardiovascular disease by Community Pharmacists in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1587–95.

Boateng D, Wekesah F, Browne JL, et al. Knowledge and awareness of and perception towards cardiovascular disease risk in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189264.

Juma PA, Mohamed SF, Matanje Mwagomba BL, et al. Non-communicable disease prevention policy process in five African countries authors. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:961.

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80.

Toupchian O, Abdollahi S, Samadi M, et al. Knowledge and attitude on cardiovascular disease risk factors and their relationship with obesity and biochemical parameters. Journal Of Nutrition And Food Security (JNFS). 2016;1(1):63–72.

Mohammad NB, Rahman NA, Haque M. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the risk of cardiovascular diseases in patients attending outpatient clinic in Kuantan, Malaysia. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2018;10:7–14.

Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sadiq L, et al. Knowledge of hypertension and other risk factors for heart disease among Yoruba rural southwestern Nigerian population. JAMMR. 2013;3:993–1003.

Aminde LN, Takah N, Ngwasiri C, et al. Population awareness of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Buea, Cameroon. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:545.

Awad A, Al-Nafisi H. Public knowledge of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1131.

George C, Andhuvan G. A population - based study on Awareness of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. Indian Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2014; 7(2).

Shafiq S. Public knowledge of cardiovascular diseases and its risk factors in Srinagar. International Journal of Medical and Health Research. 2017;3(12):69–76.

Güneş FE, Bekiroglu N, Imeryuz N, et al. Awareness of cardiovascular risk factors among university students in Turkey. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2019;20(e127):1–10.

Mukattash TL, Shara M, Jarab AS, et al. Public knowledge and awareness of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: a cross-sectional study of 1000 Jordanians. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(6):367–76.

Fahs I, Khalife Z, Malaeb D, Iskandarani M, Salameh P. The prevalence and awareness of cardiovascular diseases risk factors among the Lebanese population: a prospective study comparing urban to rural populations. Cardiol Res Pract. 2017;2017:3530902.

Ejaz S, Afzal M, Hussain M, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding modifiable risk factors of cardiovascular diseases among adults in rural community, Lahore. Int J Soc Sc Manage. 2018;5(3):76–82.

Potvin L, Richard L, Edwards AC. Knowledge of cardiovascular disease risk factors among the Canadian population: relationships with indicators of socioeconomic status. CMAJ. 2000;162(9 Suppl):S5–S11.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to all the study participants for their willingness, tolerance and cooperation offered during this study.

Funding

This work was funded by the Jakaya Kikwete Cardiac Institute. The funder had no role in the design of this study, collection of data, data analysis, interpretation of results or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP and MJ conceived the study. NM, MK, ZM, NRH, HJS, UWM, HA, and RH recruited participants and conducted all the interviews while HM, SB, JM, HLK, EC, and ZJ performed all necessary measurements and physical examinations. NM performed data entry and PP did the analysis. The corresponding author (PP) wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and other authors contributed to and approved it. All authors assume responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the analysis. All authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees (Jakaya Kikwete Cardiac Institute) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pallangyo, P., Misidai, N., Komba, M. et al. Knowledge of cardiovascular risk factors among caretakers of outpatients attending a tertiary cardiovascular center in Tanzania: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 364 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01648-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01648-1