Abstract

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains one of the major causes of death in humans. Genetic testing may allow early detection and prevention of this disease. This study aimed to investigate the association between the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) -173G/C (rs755622) polymorphism and susceptibility to CAD based on a meta-analysis.

Methods

We searched several databases to identify observational case-control studies investigating the association between the MIF -173G > C (rs755622) polymorphism and CAD risk published before July 30, 2019. Data were analyzed using the STATA software.

Results

Six studies, comprising a total of 1172 CAD cases and 1564 controls evaluated for MIF polymorphisms, were included. The occurrence of CAD was found to be associated with the C allele of the MIF rs755622 SNP in the total population (C/G, OR = 1.489, 95% CI = 1.223–1.813). Further, MIF –173G/C polymorphism was significantly associated with CAD under the allelic model in the Asian (C/G, OR = 1.775, 95% CI = 1.365–2.309) and Caucasian (C/G, OR = 1.288, 95% CI 1.003–1.654) subgroups. The data showed that the risk of CAD was higher in the population carrying the C allele.

Conclusions

We found evidence of associations between MIF -173C/G and CAD susceptibility in the Asian and Caucasian populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atherosclerosis is a chronic arterial wall inflammatory disease [1] associated with endothelial dysfunction, intimal hyperplasia, smooth muscle hyperplasia, lipid deposition, plaque formation, and micro-vein formation. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 [2]. Cytokines produced in the plaque micro-environment, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), trigger the recruitment of inflammatory cells [3]. Chemokines are released by endothelial cells, mastocytes, platelets, macrophages, and lymphocytes [4]. They mediate the migration of leukocytes to inflamed tissues and control the inflammatory reactions in various immune-mediated diseases. Chemokine expression is associated with atherosclerotic lesion development and vascular remodeling [5]. Owing to such inflammatory reactions and the accumulation of blood lipids, the artery becomes less elastic and narrower, promoting an atherosclerotic plaque formation. When vascular plaques occur in the coronary artery of the heart, they lead to a coronary artery disease (CAD) [1]. In recent years, the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) has been extensively studied in molecular functional and genetics studies. In 1966, MIF was identified as a soluble factor secreted by T cells that delayed hypersensitivity reactions and inhibited the random migration of macrophages [4]. Later studies revealed that MIF is stored in the pituitary gland and secreted during endotoxemia and plays a key regulatory role in innate immunity by counter-regulating glucocorticoids [6]. It has been currently considered to act as a chemokine-like multidirectional inflammatory cytokine and has been recognized to mediate numerous acute and chronic inflammatory diseases [7]. MIF is quite ubiquitously expressed and is an upstream immunomodulatory cytokine. It plays an important role in promoting inflammatory responses in CAD [8], diabetes [9], rheumatoid arthritis [10], septicemia [11], psoriasis [12], and other diseases. The MIF gene is located on chromosome 22q11.2, and two functional promoter polymorphisms have been studied [13]. One is a G-to-C transition at − 173 (rs755622) and the other is a (CATT)5–8 tetranucleotide repeat at − 794. The MIF − 173C allele creates a putative binding site for the transcription factor activating enhancer binding protein 4 and is associated with increased MIF gene expression and protein levels in a cell-type-dependent manner [14].

However, according to current reports, MIF − 173C/G is closely related to the production and expression of MIF, which causes the occurrence and development of CAD by promote the inflammatory response.

Some studies comparing MIF − 173C/G have found associations with CAD pathogenesis. To overcome the limitations and outcome bias of individual studies, and to address the inconsistencies in the findings among the various studies, we conducted a more comprehensive meta-analysis based on a systematic literature review to confirm whether MIF − 173C/G was associated with increased sensitivity and risk for CAD.

Methods

Data search and selection

We searched for reports on the MIF − 173G/C (rs755622) polymorphism in the PubMed, Embase, WanFang, China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases using the search terms “macrophage migration inhibitory factors,” or “MIF” or “rs755622” or “-173G/C,” and “genetic polymorphism” or “gene polymorphism” and “coronary artery disease,” or “myocardial infarction” in various combinations to identify studies that had investigated the association between MIF -173G/C and CAD, with the last search being conducted on June 14, 2019. No language restrictions were applied. In addition, we reviewed all references cited in the obtained papers, to identify additional studies that were not included in the above-mentioned electronic databases.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) assessment of the association between MIF -173 G > C and CAD risk, (2) case-control studies, and (3) sufficient genotype frequencies for calculating the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). (4) CAD was diagnosed according to the 1979 WHO criteria for CAD diagnosis: at least one major vessel with ≥50% stenosis in coronary angiography. Studies were excluded if they (1) were a duplication of a previous publication; (2) were comments, abstracts, overlapping studies, reviews, or editorial comments; (3) were family-based studies of pedigrees; (4) had no detailed genotype data and other information; and (5) had a cohort size of less than 100 subjects.

Data extraction

We extracted the following information from the selected articles: author, year of publication, country/countries, ethnicity, number of cases and controls, and genotyping methods used. In addition, we determined whether data had been analyzed correctly.

Quality assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to evaluate the quality of the studies included [15] (www.liebertpub.com/gtmb, Supplementary Fig. S1). Each study is scored for 8 items, and the scores are added up to obtain the final score, which ranges from 0 to 10 points, with a score of ≥7 points indicating a high-quality study. All authors reviewed and scored the studies. Five studies included [16,17,18,19,20] had a score of ≥7 points. One study by Bin et al. [21] on the relationship between gene polymorphism and CAD in smokers scored only 6 points, but we included this study as this score was expected to have a limited influence on the final analysis results.

Data analyses

We used Chi-squared tests to evaluate population genotype frequencies to test for the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), if P ≥ 0.05, indicate population gene genetic balance. The OR and 95% CI were calculated by the same method to evaluate the risk of CAD in different genes, with P < 0.05 indicating a significant effect. We used the Cochran’s Q test statistic and the I2 statistic to assess variation and within- and between- study heterogeneities [22]. Q-test results may be unreliable when a small number of studies is included in the meta-analysis. Therefore, a heterogeneity with P < 0.1 indicates the presence of heterogeneity [23]. We used I2 (I2 = 100% × (Q – df)/Q) to assess the heterogeneity of the studies included [11]. I2 is an index to evaluate the degree of inconsistency among the studies included and to test whether the percentage total variation among the studies was due to heterogeneity or by chance. I2 values range from 0 to 100%, and I2 values of 25, 50, and 75% were considered to indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. When I2 is greater than 50%, heterogeneity cannot be ignored, and subgroup analysis is needed to evaluate the source of heterogeneity [24]. We assessed the association between MIF -173G/C and CAD under six genetic models: an allelic model (C vs. G), homozygote model (CC vs. GG), a heterozygote model (CG vs. CC), a recessive model (CC vs. CG + GG), a dominant model (GG vs. CG + CC), and an additive model (CG vs. CC + GG). To find ethnic effects, we divided patients into two subgroups, Asians and Caucasians, and we conducted a sensitivity analysis by successively omitting one of the six studies and assessing the effect thereof on the results. Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s linear regression test were used to assess for publication bias across studies [25]. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline characteristics of eligible studies

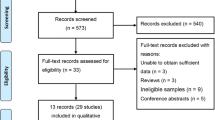

We found 50 studies based on electronic and manual searches. Three studies were excluded because they reported duplicate data, 31 were excluded from full-text review based on the title and abstract. Sixteen full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Among these, eight were not about CAD, two were not case-control studies, and thus, these studies were excluded. The six reports that met our inclusion criteria were included into our meta-analysis [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Details on the selection and exclusion processes have been shown in the flow chart in Fig. 1. Together, the six studies comprised 1172 patients with CAD and 1564 controls evaluated for MIF polymorphisms (Table 1). All studies examined the MIF -173C/G polymorphism. Characteristic features of the studies were assessed in the meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis of the association between MIF -173 C/G and CAD susceptibility

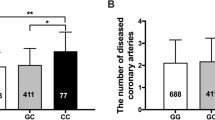

Data collected from the six studies have been summarized for gene analysis (Table 1). It was found that the gene polymorphism in healthy controls and patients with CAD was in HWE, which indicated that the gene frequency and genotypic frequency were balanced. We not only studied MIF -173C/G homozygotes and heterozygotes with CAD, but also incorporated dominant, recessive, and additional models to observe the relationships between these models and the risk of CAD, so as to conduct a more comprehensive meta-analysis. Thus, we compared allelic, homozygote, heterozygote, dominant, recessive, and additive models. Based on analysis of the total population, the risk for CAD was found to be increased by 48.9% under the allelic model (C/G: odds ratio [OR] = 1.489, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.223–1.813, P < 0.001), by 123.2% under the homozygote model (CC/GG: OR = 2.232, 95% CI = 1.559–3.197, P < 0.001), and by 106.5% under the recessive model (CC/CG + GG: OR = 2.065, 95% CI = 1.454–2.933, P < 0.001). The risk for CAD was reduced by 43.5% under the heterozygote model (CG/CC: OR = 0.565, 95% CI = 0.39–0.82, P = 0.003) and by 31.8% under the dominant model (GG/CG + CC: OR = 0.682, 95% CI = 0.535–0.871, P = 0.002). The additive model (CG vs. CC + GG: OR = 1.242, 95% CI = 0.876–1.762, P = 0.223) had no statistical significance (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure S2-S6, Table 2).

To clarify the source of heterogeneity and reduce the heterogeneity of the conclusions, we next conducted subgroup analysis in subgroups according to ethnicity.

Association between MIF -173 C/G and CAD susceptibility in the Asian population

In the Asian population, the risk for CAD was increased by 77.5% under the allelic model (C/G: OR = 1.775, 95% CI = 1.365–2.309, P < 0.001), by 250.2% under the homozygote model (CC/GG: OR = 3.502, 95% CI = 1.983–6.187, P < 0.001), and by 263.2% under the recessive model (CC/CG + GG: OR = 3.632, 95% CI = 2.073–6.361, P < 0.001), whereas the risk was reduced by 74.0% under the heterozygote model (CG/CC: OR = 0.260, 95% CI = 0.138–0.487, P < 0.001) and by 41.0% under the dominant model (GG/CG + CC: OR = 0.590, 95% CI = 0.372–0.938, P = 0.026) (Table 2).

Association between MIF -173 C/G and CAD susceptibility in the Caucasian population

In the Caucasian population, the risk for CAD was increased by 28.8% under the allelic model (C/G: OR = 1.288, 95% CI = 1.003–1.654, P = 0.047), by 64.0% under the homozygote model (CC/GG: OR = 1.640, 95% CI = 1.024–2.626, P = 0.039), and by 33.1% under the additive model (CG/CC + GG: OR = 1.331, 95% CI =1.03–1.72, P = 0.029), and the risk was reduced by 26.6% under the dominant model (GG/CG + CC: OR = 0.734, 95% CI = 0.542–0.994, P = 0.045). There was no significant effect under the recessive (CC/CG + GG: OR = 1.418, 95% CI = 0.895–2.247, P = 0.137) and heterozygote (CG/CC: OR = 0.889, 95% CI = 0.552–1.433, P = 0.629) models (Table 2).

Sensitivity and publication bias analyses

To investigate the stability of the meta-analysis, we used a sensitivity analysis. The OR value was not affected by a sequential exclusion of any of the six studies using the six genetic models. Although funnel plots are often used to evaluate publication bias, it has some unavoidable limitations, such as the need for different sample sizes for various studies and the fact that the presence of artificial subjective judgments affect the final decision. Therefore, we used Egger’s linear regression test to assess publication bias for MIF -173C/G and CAD risk. Egger’s test indicated the presence of sample bias (C vs. G: t = − 0.15, P = 0.89), which we considered to be due to the fact that the sample size was not sufficiently large; however, this did not affect the results of the analysis (Fig. 3).

Discussion

CAD, a chronic arterial wall disease, is not simply due to an accumulation of lipids in the body, but is an inflammatory disease in response to an injury, in which inflammatory cells and mediators are involved in plaque formation. MIF was the first cytokine to be considered an important mediator of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, mediating the generation of inflammatory cells. MIF is an important proinflammatory factor and chemokine. It can recruit inflammatory immune cells, such as macrophages and T lymphocytes, to participate in the inflammatory response at atherosclerotic plaques [26, 27]. It can also stimulate macrophages and lymphocytes to secrete inflammatory factors, including IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and intracellular adhesion factor, which significantly enhance the inflammatory response at atherosclerotic plaques [10]. MIF can be expressed at low levels in vascular smooth muscle cells and vascular endothelial cells, but when atherosclerotic plaques occur in the blood vessels, the production of MIF increases rapidly, suggesting it may be involved in the occurrence of atherosclerosis. In recent years, MIF has been explored in genetic and molecular functional studies [28]. The MIF -173C allele establishes a hypothetical binding site for transcription factor activating enhancer binding protein 4, which may increase MIF gene and protein expression [14].

The MONICA/KORA Augsburg study reported that the MIF rs755622 C allele increased the susceptibility to juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and celiac disease associated with severe ulcerative colitis [17, 20, 26, 29]. The hypothesis that MIF rs755622 polymorphisms regulate MIF levels only in certain conditions, e.g., in response to infection, trauma, or autoimmunity, was confirmed in a cardiopulmonary bypass study [30]. Only MIF -173C allele carriers receiving revascularization and cardiopulmonary bypass had elevated systemic MIF levels, indicating genotype changes in MIF expression affected by trauma and injury. Alternatively, rs755622 may be mainly related to localized MIF expression, that is, MIF expression can be increased in certain cell types or tissues, such as atherosclerotic lesions. However, there is currently no evidence supporting this speculation.

The mechanistic link between MIF -173C alleles and disease remains unclear, as most studies focused on genotyping data and did not evaluate circulating MIF levels. Nevertheless, we can unravel the correlation between MIF rs755622 polymorphism and CAD based on published articles. One study showed that MIF -173C was associated with an increased risk CAD in German women, based on an average follow-up period of 10 years [31]. In the Han Chinese too, MIF -173C has been identified as a CAD risk factor [17, 19]. Yang et al. reported that plasma MIF levels may be used to predict the severity of coronary lesion [32]. Meanwhile, MIF -173G/C polymorphism influences the plasma levels of MIF and TNF-α in some inflammatory disorders [33, 34]. However, the precise regulatory mechanisms of this association remain unclear. Relevant studies suggest that the MIF rs755622 G/C polymorphism may play a critical role in the etiology of coronary artery lesions and may have predictive value for their severity. The analysis of more MIF polymorphisms may help to identify individuals with potential CAD risk, and identifying targeted MIF variants in CAD patients may be beneficial for risk stratification and management.

In our systematic meta-analysis, including six studies comprising approximately 2700 participants, MIF -173C/G was associated with CAD risk in the overall population and in two ethnic subgroups (Asians and Caucasians). CAD risk was increased in the allelic, recessive, and homozygote models, whereas it was decreased in the dominant and heterozygote models. To identify and reduce the source of heterogeneity, we analyzed the Asian and Caucasian populations separately. We could conclude that people with MIF -173C were more likely to develop CAD, which might be related to increased MIF expression and production, which aggravated the inflammatory reaction, leading to the occurrence and development of CAD. There are several potential causes of the observed heterogeneity. First, study characteristics, including the source population for the case-control groups, race, research design, CAD subtypes, sample size, genotyping methods and specific typing can differ among studies and may explain the differences in subgroup analysis. Second, ethnic groups are genetically different, and clinical manifestations depend on factors such as age, sex, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, which may be related to CAD heterogeneity [35]. Third, different populations have different lifestyles, including eating habits, exercise patterns, which may affect CAD onset and progression.

Our meta-analysis had some strengths. First, a comprehensive meta-analysis to provide substantial evidence of the association between MIF -173C/G and CAD, which would allow a more accurate judgment of this gene polymorphism in the treatment of human CAD, had not been conducted to date. Second, we selected Chinese and foreign studies, including two different ethnicities, for which we conducted subgroup analyses, which allowed us to find the source of heterogeneity and further assess the risk of MIF -173C/G for CAD in these two populations. In contrast, our study had several limitations. First, it included only six studies. Therefore, additional information from large-cohort studies on MIF -173C/G and CAD is required to reduce the publication bias. Second, numerous factors can influence the occurrence and development of coronary heart disease, and we did not consider other polymorphisms in MIF, such as -794CATT5–8, or in other related genes. Third, despite the inclusion of different ethnic groups, populations may have different habits, including different eating and lifestyle habits, which should be considered more carefully in future studies. Fourth, more research is needed to confirm the relevance of -173 C/G to the risk of CAD and to clarify the underlying mechanism.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis demonstrated that MIF -173C/G polymorphism was associated with CAD susceptibility. MIF -173C/G may regulate and increase the risk of CAD by increasing MIF secretion. Our findings may help to understand the effects of CAD-related genes in total the population and in different ethnic groups, and lay a foundation for the prevention of coronary heart disease in the future.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study have been included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- MIF:

-

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Chen Z, Sakuma M, Zago AC, Zhang X, Shi C, Leng L, Mizue Y, Bucala R, Simon D. Evidence for a role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(4):709–14.

Su SA, Ma H, Shen L, Xiang MX, Wang JA. Interleukin-17 and acute coronary syndrome. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2013;14(8):664–9.

Jednacz E, Rutkowska-Sak L. Atherosclerosis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Mediat Inflamm. 2012;2012:714732.

Leng L, Bucala R. Insight into the biology of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) revealed by the cloning of its cell surface receptor. Cell Res. 2006;16(2):162–8.

Filippatos G, Parissis JT, Adamopoulos S, Kardaras F. Chemokines in cardiovascular remodeling: clinical and therapeutic implications. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3(2):139–47.

Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Korbonits M, Pyle M, Gueorguiev M, Meinhardt A, Metz C, Petrovsky N, Popovic V, Bucala R, et al. Response of serum macrophage migration inhibitory factor levels to stimulation or suppression of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in normal subjects and patients with Cushing's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(4):1834–40.

Xia W, Zhang F, Xie C, Jiang M, Hou M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor confers resistance to senescence through CD74-dependent AMPK-FOXO3a signaling in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:82.

Zernecke A, Bernhagen J, Weber C. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117(12):1594–602.

Sanchez-Zamora YI, Juarez-Avelar I, Vazquez-Mendoza A, Hiriart M, Rodriguez-Sosa M. Altered macrophage and dendritic cell response in Mif−/− mice reveals a role of Mif for inflammatory-Th1 response in type 1 diabetes. J Diab Res. 2016;2016:7053963.

Baugh JA, Chitnis S, Donnelly SC, Monteiro J, Lin X, Plant BJ, Wolfe F, Gregersen PK, Bucala R. A functional promoter polymorphism in the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene associated with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Genes Immun. 2002;3(3):170–6.

Bernhagen J, Calandra T, Bucala R. The emerging role of MIF in septic shock and infection. Biotherapy. 1994;8(2):123–7.

Morales-Zambrano R, Bautista-Herrera LA, De la Cruz-Mosso U, Villanueva-Quintero GD, Padilla-Gutierrez JR, Valle Y, Parra-Rojas I, Rangel-Villalobos H, Gutierrez-Urena SR, Munoz-Valle JF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promoter polymorphisms (−794 CATT5-8 and −173 G>C): association with MIF and TNFalpha in psoriatic arthritis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(9):2605–14.

Budarf M, McDonald T, Sellinger B, Kozak C, Graham C, Wistow G. Localization of the human gene for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) to chromosome 22q11.2. Genomics. 1997;39(2):235–6.

Donn R, Alourfi Z, De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Zeggini E, Lunt M, Stevens A, Shelley E, Lamb R, Ollier WE, et al. Mutation screening of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene: positive association of a functional polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(9):2402–9.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D. Methods work group TUSPSTF: current methods of the US preventive services task force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 Suppl):21–35.

Qian L, Yin RP. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Promoter Polymorphisms (−173 G>C) : Relationship with Coronary Atherosclerotic Disease Subjects. J Med Res. 2018;47(4):32–5.

Shan ZX, Fu YH, Yu XY, Deng CY, Tan HH, Lin QX, Yu HM, Lin SG. Association of the polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene with coronary heart disease in Chinese population. Chin J Med Genet. 2006;23(5):548–50.

Luo JY, Xu R, Li XM, Zhou Y, Zhao Q, Liu F, Chen BD, Ma YT, Gao XM, Yang YN. MIF gene polymorphism rs755622 is associated with coronary artery disease and severity of coronary lesions in a Chinese Kazakh population: a case-control study. Medicine. 2016;95(4):e2617.

Ji K, Wang X, Li J, Lu Q, Wang G, Xue Y, Zhang S, Qian L, Wu W, Zhu Y, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to inflammatory coronary heart disease. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:315174.

Tereshchenko IP, Petrkova J, Mrazek F, Lukl J, Maksimov VN, Romaschenko AG, Voevoda MI, Petrek M. The macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene polymorphism in Czech and Russian patients with myocardial infarction. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2009;402(1–2):199–202.

Lin B, Fu GS, Li CL, Huang H, Mao HH, Zhang P, Zhou BQ. Association of MIF - 173 gene polymorphism with coronary heart disease in Chinese cigarette smoking population. Clinical Education of General Practice. 2008;6(1):31–4.

Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. Bmj. 1997;315(7121):1533–7.

Munafo MR, Flint J. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2004;20(9):439–44.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Jama. 2006;295(6):676–80.

Schober A, Bernhagen J, Weber C. Chemokine-like functions of MIF in atherosclerosis. J Mol Med. 2008;86(7):761–70.

Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue H, Gregory JL, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, Dewor M, Georgiev I, Schober A, Leng L, et al. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):587–96.

Kleemann R, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: critical role in obesity, insulin resistance, and associated comorbidities. Mediat Inflamm. 2010;2010:610479.

Llamas-Covarrubias MA, Valle Y, Bucala R, Navarro-Hernandez RE, Palafox-Sanchez CA, Padilla-Gutierrez JR, Parra-Rojas I, Bernard-Medina AG, Reyes-Castillo Z, Munoz-Valle JF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): genetic evidence for participation in early onset and early stage rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine. 2013;61(3):759–65.

Lehmann LE, Schroeder S, Hartmann W, Dewald O, Book M, Weber SU, Schewe JC, Stuber F. A single nucleotide polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is related to inflammatory response in coronary bypass surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2006;30(1):59–63.

Herder C, Illig T, Baumert J, Muller M, Klopp N, Khuseyinova N, Meisinger C, Martin S, Thorand B, Koenig W. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and risk for coronary heart disease: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study, 1984-2002. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200(2):380–8.

Yang LX, Guo RW, Qi F, Miao GH, Wang XM, Shi YK, Li MQ. Association between plasma macrophage migration inhibitory factor concentration and coronary artery lesion severity. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2008;36(10):912–5.

Karakaya B, van Moorsel CH, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Huizinga TW, Ruven HJ, van der Vis JJ, Grutters JC. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) -173 polymorphism is associated with clinical erythema nodosum in Lofgren's syndrome. Cytokine. 2014;69(2):272–6.

Radstake TR, Sweep FC, Welsing P, Franke B, Vermeulen SH, Geurts-Moespot A, Calandra T, Donn R, van Riel PL. Correlation of rheumatoid arthritis severity with the genetic functional variants and circulating levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3020–9.

Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2128–32.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National key Research and Development project Foundation of China (no. 2018YFC1312804). This study was supported by research grants from the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University to Dr. Yang Yining. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y.L., Q.J.C., J.Y.Z., and Y.N.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. D.Y.L., J.Y.Z., Q.Z. analyzed the data. D.Y.L., Q.J.C., J.Y.Z., F.L., X.M.L., X.M.G., and Y.N.Y. contributed materials and analytic tools. D.Y.L., Q.J.C., J.Y.Z wrote the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by The Regional Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Supplementary Table S1

. Scale for Methodological Quality Assessment.

Additional file 2

Supplementary Figure S2 Forest plot of MIF -173C/G rs755622 in subgroup analysis for homozygote model comparison (CC vs.GG). Supplementary Figure S3 Forest plot of MIF -173C/G rs755622 in subgroup analysis for recessive model comparison (CC vs.CG + GG). Supplementary Figure S4 Forest plot of MIF -173C/G rs755622 in subgroup analysis for heterozygote model comparison (CG vs.CC). Supplementary Figure S5 Forest plot of MIF -173C/G rs755622 in subgroup analysis for dominant model comparison (GG vs.CG + CC). Supplementary Figure S6 Forest plot of MIF -173C/G rs755622 in subgroup analysis for additive model comparison (CG vs.CC + GG).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, DY., Zhang, JY., Chen, QJ. et al. MIF -173G/C (rs755622) polymorphism modulates coronary artery disease risk: evidence from a systematic meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01564-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01564-4