Abstract

Background

An aberrant origin of the left coronary artery (LCA) from the right coronary cusp (RCC) is an extremely rare congenital anomaly. We here report on successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a patient presenting with acute coronary syndrome and an aberrant origin of the LCA from the RCC.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man presented at our emergency department with recurrent resting chest pain. Following unsuccessful attempts at visualizing the left coronary artery using Judkins left and Amplatz catheters, an aortogram using a pigtail catheter suggested anomalous left coronary artery origin and showed a significant occlusive lesion at proximal left anterior descending artery. A Judkins right 4 guiding catheter was placed around the left coronary ostium and exchanged for a Judkins left 3.5 guiding catheter after introducing a .014" coronary long wire into the left circumflex artery. With excellent angiographic visualization and guide support, a drug-eluting stent was then successfully implanted. Cardiac computed tomography (CT) demonstrated left coronary artery origin from right coronary cusp.

Conclusion

This report presents a case of LCA originating from the RCC accompanied with acute coronary syndrome that was treated with successful PCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronary artery anomalies are rare findings in about 1% to 2% of adults [1], with aberrant origin of the left coronary artery (LCA) from the right coronary cusp (RCC) being extremely rare (0.15% incidence) [2]. Furthermore, coronary artery anomalies presenting with acute coronary syndrome are also uncommon, and often are challenging to manage [3]. We report on successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a patient with acute coronary syndrome and LCA originating from the RCC.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia presented to our emergency department complaining of recurrent resting chest pain (Canadian Cardiovascular Society Class III). A physical examination revealed that the patient’s blood pressure was 80/40 mmHg, his pulse rate was 61 beats per minute, and that he displayed an absence of any abnormal cardiac or respiratory sounds. An electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm without significant ST-T wave abnormality, and chest X-ray findings were unremarkable. His serum troponin I peaked at 0.09 mcg/L (ULN ≤0.05 mcg/L) within 24 h of presentation. Under the clinical diagnosis of unstable angina, he was treated in accordance with acute coronary syndrome guidelines [4, 5].

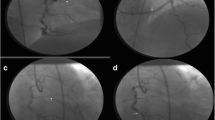

While using the femoral approach with a 6-Fr sheath, no luminal stenosis was apparent at the right coronary artery (RCA) in RCA angiography. Left main coronary artery could not be engaged with conventional diagnostic catheters, such as Judkins Left 4 and Amplatz 1.0, and nonselective angiography using pig-tail catheter raised suspicion that the left coronary artery (LCA) was originating from the right coronary cusp (RCC) with an up-to-90% occlusive lesion present at the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Fig. 1a). After a Judkins right 4 guiding catheter was placed around the left coronary ostium, a .014″ coronary long wire (RG3, Asahi-Intecc, Nagoya, Japan) was successfully introduced into the left circumflex artery (LCx). Because the Judkins right guiding catheter was too short to reach the left coronary ostium, it was exchanged with a Judkins left 3.5 guiding catheter (Fig. 1b) instead, which was deeply intubated into the left main coronary artery with ballooning support on the LCx wire. Following guiding catheter stabilization, angiography clearly revealed a tubular eccentric proximal LAD with 90% stenosis (Fig. 1c). After passing an .014″ coronary guide wire (Runthrough®, TERUMO Inc., Japan) through the lesion, balloon angioplasty was performed with a 3.0 × 15-mm balloon. A 4.0 × 18-mm drug-eluting stent (XIENCE Alpine®, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was then implanted with adjuvant ballooning performed with a 4.5 × 10-mm balloon. After successful proximal LAD revascularization, final angiography showed no residual stenosis or complications (Fig. 1d). The patient tolerated the procedure well, and appeared in good condition postoperatively. Two days later, computed tomography coronary angiography to establish the LCA system course revealed an anomalous origin of LAD and LCx from the right sinus of Valsalva (Fig. 2).

a Non-selective coronary angiography using a pig-tail catheter demonstrated anomalous origin of left coronary arteries and a significant occlusive lesion at the proximal left anterior descending artery. b With a Judkins right guiding catheter, a .014″ coronary long wire was introduced to the left circumflex artery (arrow). c For superior back-up support, the Judkins left guiding catheter was exchanged revealing significant stenosis at the left anterior descending artery (arrow). d Following percutaneous coronary intervention, there was no residual stenosis or dissections observed

a Computed tomography coronary angiography revealed anomalous origin of the left coronary arteries from the right coronary cusp (arrow) in three-dimensional reconstructed image. b Computed tomography coronary angiography showed the anomalous origin of left coronary artery and traveling behind the pulmonary artery (arrow)

Discussion and Conclusions

The present report illustrates the use of an effective PCI approach in the setting of an aberrant LCA from the RCC, which is very rare, with a reported incidence of only 0.02% to 0.15% [1, 2, 6,7,8]. In the few cases reported from Korea, this clinical condition has been treated either with conservative care or open heart surgery [9, 10], and one with PCI in which all three vessels arose from the right coronary ostium and an Amplatz right guiding catheter was engaged into the ostium of the LCx [11, 12]. Shah et al. reported a case of PCI in a patient with an anomalous left main originating from the right sinus of Valsalva that was successfully treated with a Judkins Left 3.5 guide support [13]. Unlike previous cases, our patient showed the LCA from the RCC separately from the right coronary ostium being successfully treated with PCI.

Approximately 0.14% of anomalous coronary arteries originating from the opposite sinus of Valsalva showed significant vessel compression which could be associated with major adverse cardiac events [14]. Because of reported possible associations between coronary anomalies and serious adverse clinical events [15,16,17,18], the prompt diagnosis and management of an anomalous coronary artery origin is important during acute coronary syndrome, as underscored by the present case.

According to ACC/AHA guidelines, possible anomalous coronary artery origin from the opposite sinus of Valsalva should be identified for evaluation of aborted sudden cardiac death or life-threatening arrhythmia [19]. However, coronary artery anomalous origins are often found incidentally at the time of invasive coronary angiography. While conventional angiography has projectional vascular overlap limitations, ECG-gated multidetector CT coronary angiography allows for the accurate imaging of an anomalous coronary artery origin, course, and relationship with cardiac structures and major arteries [20,21,22]. As illustrated here, CT coronary angiography should be performed even after successful revascularization to detect malignant anomalous coronary origin from the opposite sinus of Valsalva.

In conclusion, we present a patient with anomalous LCA originating from the RCC accompanied with acute coronary syndrome, who underwent successful percutaneous coronary intervention.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending artery

- LCA:

-

Left coronary artery

- LCx:

-

Left circumflex artery

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- RCC:

-

Right coronary cusp

References

Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Catheter Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990;21(1):28–40.

Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies: an entity in search of an identity. Circulation. 2007;115(10):1296–305.

Marchesini J, Campo G, Righi R, Benea G, Ferrari R. Coronary artery anomalies presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Pract. 2011;1:e107.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, Granger CB, Lange RA, Mack MJ, Mauri L, others. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation. 2016;134:e123–55.

Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, others. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315.

Laureti JM, Singh K, Blankenship J. Anomalous coronary arteries: a familial clustering. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28(10):488–90.

Alexander RW, Griffith GC. Anomalies of the coronary arteries and their clinical significance. Circulation. 1956;14(5):800–5.

Wilkins CE, Betancourt B, Mathur VS, Massumi A, De Castro CM, Garcia E, Hall RJ. Coronary artery anomalies: a review of more than 10,000 patients from the Clayton Cardiovascular Laboratories. Tex Heart Inst J. 1988;15(3):166–73.

Lee KM, Lee MH, Lee JH, Kwon KH, Kwon HM, Cho SY, Kim SS. Acute myocardial infarction as a complication of anomalous left coronary artery origin from right coronary sinus. Korean Circ J. 1996;26(4):901–5.

Yang DK, Cha KS, Kim BK, Lee SH, Park TH, Kim ET, Kim MH, Kim YD, Woo JS, Kim JS. Anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of valsalva. Korean Circ J. 2000;30(9):1165–9.

Venturini E, Magni L. Single coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva. Heart Int. 2011;6(1):e5.

Cho HO, Cho KH, Jeong YS, Ahn SG, Choi SJ, Yoo JY, Kim EJ. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the right sinus of valsalva, which presented as acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2006;36(12):817–9.

Shah N, Cheng VE, Cox N, Soon K. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of an Anomalous Left Main Coronary Artery Arising from the Right Sinus of Valsalva. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24:e123–6.

Opolski MP, Pregowski J, Kruk M, Witkowski A, Kwiecinska S, Lubienska E, Demkow M, Hryniewiecki T, Michalek P, Ruzyllo W, others. Prevalence and characteristics of coronary anomalies originating from the opposite sinus of Valsalva in 8,522 patients referred for coronary computed tomography angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(9):1361–7.

Liberthson RR. Sudden death from cardiac causes in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(16):1039–44.

Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276(3):199–204.

Taylor AJ, Byers JP, Cheitlin MD, Virmani R. Anomalous right or left coronary artery from the contralateral coronary sinus: "high-risk" abnormalities in the initial coronary artery course and heterogeneous clinical outcomes. Am Heart J. 1997;133(4):428–35.

Basso C, Maron BJ, Corrado D, Thiene G. Clinical profile of congenital coronary artery anomalies with origin from the wrong aortic sinus leading to sudden death in young competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(6):1493–501.

Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr, Hijazi ZM, others. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):e143–263.

Kacmaz F, Ozbulbul NI, Alyan O, Maden O, Demir AD, Balbay Y, Erbay AR, Atak R, Senen K, Olcer T, others. Imaging of coronary artery anomalies: the role of multidetector computed tomography. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19(3):203–9.

Tariq R, Kureshi SB, Siddiqui UT, Ahmed R. Congenital anomalies of coronary arteries: Diagnosis with 64 slice multidetector CT. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(8):1790–7.

Torres FS, Nguyen ET, Dennie CJ, Crean AM, Horlick E, Osten MD, Paul N. Role of MDCT coronary angiography in the evaluation of septal vs interarterial course of anomalous left coronary arteries. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2010;4(4):246–54.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements.

Funding

There was no funding received for this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All available information is contained within the present manuscript.

Disclosures

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JHL and JSP drafted the manuscript and performed angioplasty. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent information is available for review from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, JH., Park, JS. Successful percutaneous coronary intervention in the setting of an aberrant left coronary artery arising from the right coronary cusp in a patient with acute coronary syndrome: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 17, 186 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0621-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0621-3